99 Problems and Maduro is One

What does a 1990s hip-hop artist from Brooklyn, and an oil-rich South American country have in common? Surprisingly, a shared struggle. Jay-Z famously faced 99 problems, while Venezuela’s was one, much larger, issue: Nicolás Maduro.

Their career paths were equally unconventional. Jay-Z transitioned from a high school dropout to a global hip-hop icon whilst Nicolás Maduro journeyed from a bus driver to the President of Venezuela. By comparison, it makes my not-so-meteoric rise from a university bartender to an investment specialist seem relatively spiritless.

Both also faced critical turning points at the age of 24: Jay-Z was stopped by New York City police, sparking the inspiration for his hit song “99 Problems,” while Maduro’s story was just beginning with a move to Cuba.

In this blog, I delve into the downfall of Venezuela, exploring how corruption and socialism stifled what could have been one of Latin America’s great success stories.

From Cuba to Caracas

The move to Havana was significant for Maduro, which he made alongside other left-centric South American militants who viewed Cuba’s leader at the time, Fidel Castro, as the shining light of socialism. His initial time there had an important impact on his ideological development with Maduro receiving training at the prestigious Escuela Nico Lopez, an institution known for its rigorous political education programs.

This period in Cuba shaped Maduro’s political beliefs and deepened his commitment to socialist ideology. The experience also strengthened his ties with Cuban political leaders and the country’s model of governance, which later influenced his political career in Venezuela. To this day, Cuba remains one of Venezuela’s strongest supporters.

Following his move back to Venezuela, Maduro embarked on a political climb that would make even the most hardened politician blush. From a bus driver to a trade union leader, he was soon elected to the National Assembly where his relationship with the current leader of Venezuela, Hugo Chávez, began.

Under Chávez, he became President of the National Assembly, then Minister of Foreign affairs, and finally Vice-President. He was Vice-President until Chávez’s death in 2013, after which he became President. From a trade union leader to the President of Venezuela within thirteen years is nothing short of remarkable.

New leader, same leadership

Chávez’s death coincided with a troublesome period for Venezuela, with Maduro inheriting an economy creaking under the pressure of socialism and economic mismanagement. His presidency soon began after the death of Chávez with an election held in April 2013 which Maduro won by the smallest of margins. The result was heavily contested by the opposition which was, in hindsight, a warning sign for things to come.

Those hoping a new leader would help reinvigorate the economy or impose economic reform to steer the country back towards prosperity were quickly disappointed. Maduro and Chávez were very much cut from the same cloth, with Maduro doubling down on policies that had set Venezuela down its path of discontent.

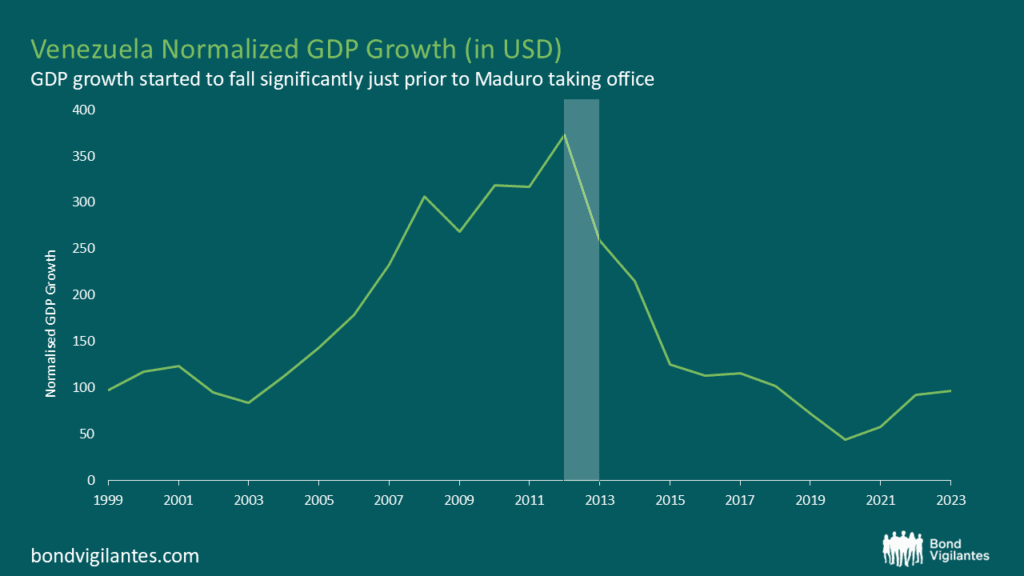

Maduro’s economic policies focused on maintaining price controls, currency exchange controls, and extensive social spending, continuing Chávez’s legacy. These measures led to significant economic distortions, including rampant inflation, a thriving black market for currency, and severe shortages of basic goods. The fixed exchange rate policy drained foreign reserves, while price controls disincentivised production, which exacerbated scarcity. Additionally, heavy reliance on oil revenues made the economy vulnerable to oil price fluctuations. These policies contributed to a deepening economic crisis, with a significant crash in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth looming.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg, as at 31 August 2024

Double trouble, oil and spoil

It is hard to overstate just how closely Venezuela’s economy is tied to oil, with the country being perhaps the purest representation of what a petrostate looks like. Estimates vary, but at its peak in 2012, oil accounted for 96% of total exports and nearly half of the country’s fiscal revenue. Chávez, for some time, used the significant oil reserves, which account for around 18% of the world’s total, to fund socialist policies. In the despot’s eyes, his country’s oil reserves were a free lunch, but sadly, there is no such thing; the cost eventually came in the form of the Dutch Disease (an economic phenomenon where the discovery of a natural resource, like oil, leads to a decline in other sectors due to currency appreciation and resource allocation shifts).

The boom in oil revenues created a significant flow of foreign capital into the country, which led to a sharp appreciation of the local currency and cheaper imports. Over time this sucked labour and capital away from other sectors within the economy, such as agriculture and manufacturing – sectors that typically provide longer-term stability and infrastructure to a country.

The dependence on oil, intertwined with broader economic mismanagement and the subsequent debt accumulation required to mitigate the loss in government revenues, ultimately led to hyperinflation, creating a vicious cycle of rising prices and economy instability.

It could have worked out so differently for the Venezuelan population. The significant surplus of oil, coupled with the rise in oil prices, should have served as a strong base for the economy to thrive. Instead, the revenues were spent on policies that offered zero future value to the treasury and created enormous fiscal pressures when oil prices fell, and the policies remained in place.

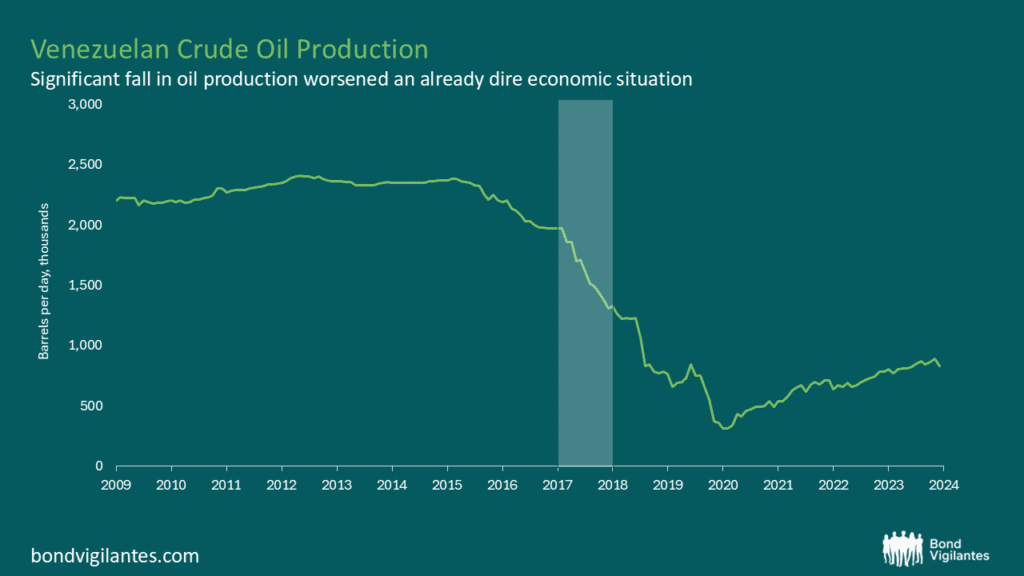

The crash in oil prices between 2012 and 2015, which saw prices fall by around two-thirds, was already a huge factor in Venezuela’s slumping GDP, and worsening economic health. But then Venezuelan oil production also began to fall materially from 2017 onwards, further weighing on the economy.

Venezuela’s output decline began in 2015 following years of mismanagement, corruption and lack of investment in the state-owned oil company Petroleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). Aging infrastructure and the brain drain of skilled workers exacerbated operational inefficiencies. The result was catastrophic: oil output – the backbone of Venezuela’s economy – drastically declined, leading to severe revenue shortfalls. The initial fall in oil production came as a result of a ‘death by a thousand cuts’ self-imposed by the Venezuelan government, but it was perhaps the US who ultimately dealt the fatal blow in 2017 when sanctions severely restricted Venezuela’s ability to monetise its vastest assets.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg, as at 31 August 2024

Spreads, sanctions, and suspicious elections

By the time Maduro took power, there was little goodwill left with the people who were supposedly the benefactors under the socialist regime. Given the severe increase in economic uncertainty and a sense that the government’s policies were not delivering what had been promised to the people, Venezuelans began widespread protests.

Backed into a corner by the unravelling of socialism and an angry populace, Maduro became even more authoritarian, seeking to oppress those who wanted to be heard. Unfortunately, dictators rarely listen; instead, they merely await their turn to speak. Maduro’s response came in the form of violent oppression, crackdowns, and arrests. Human rights abuses were widely reported which led to the first of many sanctions being imposed by the US in 2014.

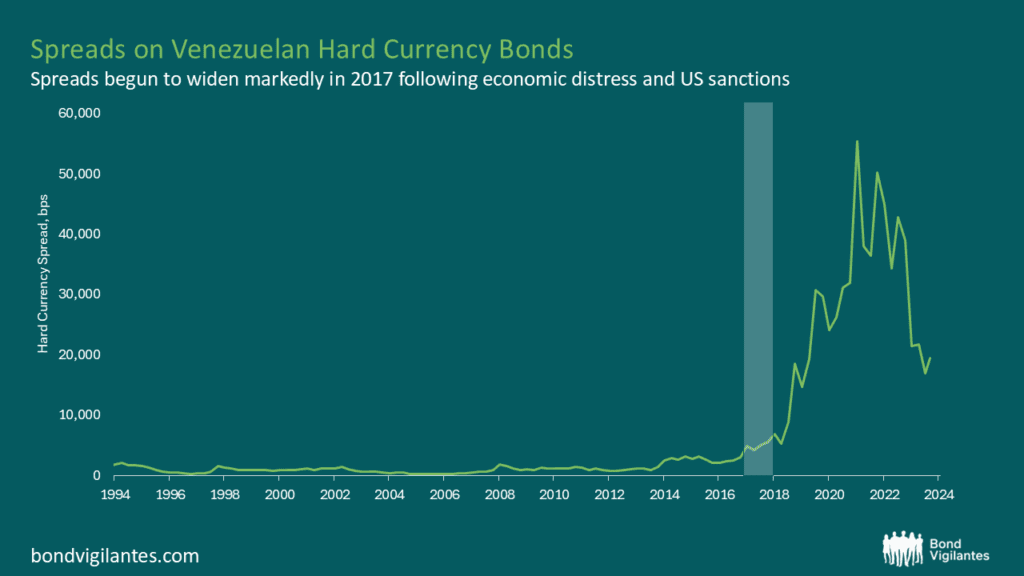

Markets were largely unmoved during Chávez’s rule but became more reactive once Maduro took power. The chart below highlights that, for a significant period, spreads on Venezuela’s hard currency bonds were well within a reasonable range (Venezuela was rated as high as BB- before 2005). However, from 2014, they began to widen due to economic uncertainty and increased scrutiny from the international community. After 2017, spreads saw the most widening, initially due to the worsening economy and slowdown in oil production, and later because of the sanctions imposed by President Trump.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg, as at 31 August 2024

Trump’s sanctions were significant and far more wide-reaching than those introduced in 2014, which were primarily at the individual level. Trump’s executive order prohibited the Venezuelan government and PDVSA (the Venezuelan state-owned oil and natural gas company) from dealing with new debt or equity. The aim was simple and engineered to cut off the Venezuelan government from any source of financing from US financial markets.

The sanctions exacerbated an already dire economic crisis. Venezuela was already facing hyperinflation, a collapse in public services, and shortages of food, medicine, and essential goods, which led to a worsening of the humanitarian crisis. Millions of Venezuelans experienced increased poverty, malnutrition, and healthcare deficiencies, prompting a mass exodus of refugees, with some estimates putting the number at eight million.

In 2018, five years after his initial victory, Maduro called another election. Concerns about the lack of transparency in the 2013 election were quickly realised, with the 2018 outcome being widely considered illegitimate and barely recognised by the international community, barring a few of Maduro’s allies such as Russia, China, and Cuba.

His second term was very much business as usual for Maduro, who sought to consolidate power whilst being kept afloat by the remaining oil trading partners, who were, funnily enough, the same countries that had legitimised his presidency. However, it also saw signs of the relationship with the US beginning to thaw.

In 2023, the US began to remove some of the sanctions with the aim of addressing the humanitarian and economic pressure facing the Venezuelan population. The basis of this was that Maduro and the leader of the opposition party had met in Barbados with international observers present, during which Maduro made a number of concessions, including a promise to allow a free and fair election.

The US, now led by President Biden, welcomed the Barbados Agreement, and began to remove some of the sanctions imposed, allowing Chevron to resume limited operations in the country but more importantly, allowing Venezuela to regain access to capital markets.

However, it wasn’t long before Maduro reverted to his mean. Ahead of the election, Maduro took measures to silence the opposition by effectively disqualifying certain individuals from running against him, including the incredibly popular Maria Machado. The failure of Venezuela to allow a fair vote, as well as the renewal of their territorial dispute with Guyana over the oil-rich Essequibo region, led the US to reimpose sanctions in April 2024.

The political dark arts employed by Maduro eventually saw 74 year-old Edmundo Gonzalez Urrutia run against him. Perhaps Maduro saw Gonzalez as a weak link, but the opposition united behind him, and Gonzalez soon began to poll very well with the public.

With a unified opposition party and a 30-point lead in polls, Venezuelans were afforded a sense of hope that a change in guard was on its way. But hope soon turned to despair, albeit with very little surprise. A few days after the election, Maduro declared himself victorious with 51% of the vote.

For those of us (myself included) who consider the 2012 Ryder Cup to be the greatest comeback in history, the overturning of a 30-point poll deficit makes the Miracle of Medinah pale in comparison to the Miracle of Maduro.

And so we are left where we began, with Maduro as the president of Venezuela, eleven years after his first disputed election. It is, of course, the Venezuelans who have paid the price for his rule, and the question of what comes next for the country is an uncomfortable one.

A rule like Maduro’s is built on the premise of equality, such is socialism’s core tenet. But the difference between those who recently ran for presidency could not be greater. Maduro, reacting with violence to suppress those who questioned his victory, is about to begin another term as president.

But Gonzalez, widely recognised as Venezuela’s legitimate President-elect, is facing lengthy criminal proceeding for crimes that are unclear to most. For now, he has been granted political asylum in Spain, shielding away from Maduro who continues to force his opposition into retreat.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.