Navigating the curve – The allure and risks of long-dated US Treasuries

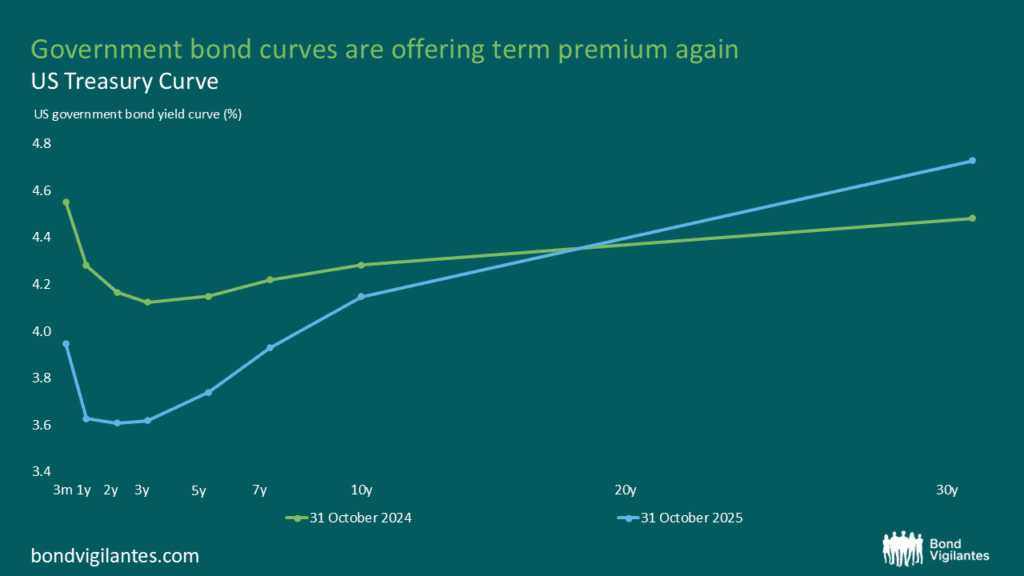

Compared to a year ago, the US Treasury curve has steepened considerably. While yields at the front end have dropped due to anticipated rate cuts, the long end of the curve has not budged. In fact, long-end bonds have sold off, giving bond investors the opportunity to lock in elevated yields. That’s quite a tempting thought, considering we’re talking about the US, which sets the global reference rate for many asset classes.

Source: Bloomberg, 31 October 2025

In economies where GDP growth is constrained by high levels of debt and unfavourable demographics, governments either need to hope for a productivity boom or be prudent with spending plans to keep debt-to-GDP metrics in check. Achieving the latter can be challenging given the pressures of rising geopolitical tensions and the structural incentives in democratic systems that often prioritise short-term spending commitments during election cycles. This, in turn, increases the odds of inflation playing a larger role in achieving fiscal sustainability in the future. In a world of financial repression, an opportunity to lock in positive real yields at 2-2.5% is worth considering. But, it is not a slam dunk. Below, we share are a few concerns that keep us on the sidelines for now.

Risk one: absence of productivity boom

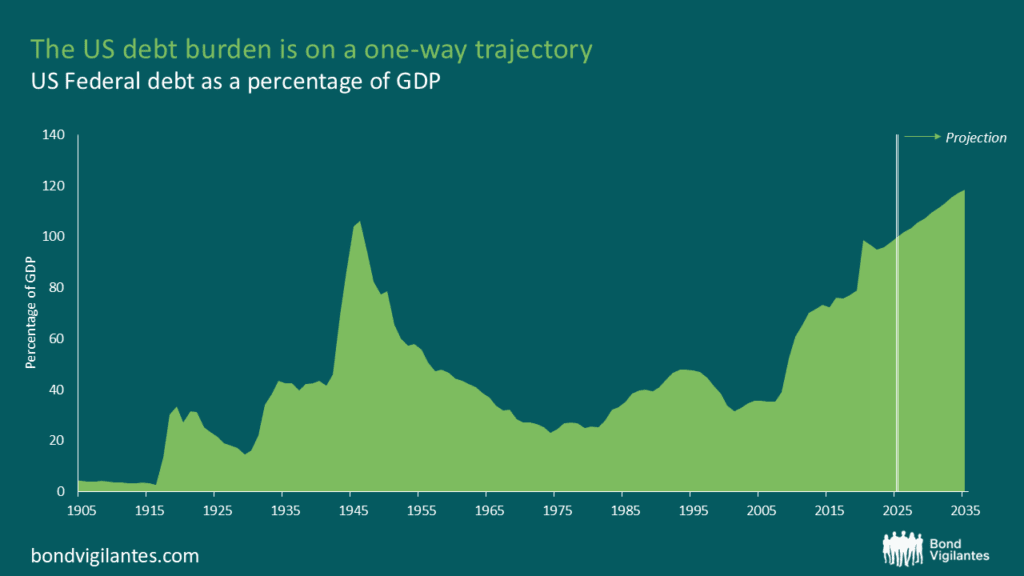

Running fiscal deficits when yields are high and debt-to-GDP levels are elevated can be risky business. The US is currently doing just that which explains why the bond market has revalued the compensation it demands for owning long-dated US Treasuries. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) sees federal debt rise from 100% to 118% of GDP by 2035, reporting the highest point in US history.

Source: Congressional Budget Office

Earlier this year, Deutsche Bank calculated the budget deficit the US must maintain to stabilise its debt metrics. According to their calculations, the US would need to run a primary budget deficit-to-GDP ratio that is no larger than 1.2% to keep debt-to-GDP stable over the long run. With the fiscal package estimated to keep budget deficits as a share of GDP between 5% and 7% over the next few years, deficits of that size look unsustainable in the absence of a productivity boom. Hopes for productivity gains through AI are high. If the story holds up and the much-hoped-for productivity gains materialise, then the US fiscal situation could suddenly look much brighter. Having said that, the CBO also notes that if productivity growth is 0.5% slower per year compared to their baseline assumption, debt could surge to over 200% of GDP by 2055. This highlights how sensitive debt assumptions are, increasing the risk of policy errors that could lead to further repricing of long-dated US bonds.

Risk two: erosion of Fed independence

In August, President Trump attempted to remove Lisa Cook from the Fed’s board of governors, citing allegations that she falsified records to obtain favourable terms on a mortgage before joining the central bank in 2022. Although the Supreme Court ruled that Cook, who is perceived as a hawkish board member, could remain in her position temporarily, Trump’s move could indicate an attempt to increase his influence over the Fed. The Fed may face repeated pressure if its monetary policies do not align with the White House’s political priorities. Jerome Powell’s term as Federal Reserve chair ends in May 2026, and Trump has stated that he will not nominate “Too-Late” Powell for another term. A new Fed chair might take a more dovish stance, increasing the risk that the Fed opts for lower interest rates to stimulate economic growth. One can argue that the US economy has become more resilient, given that 81% of GDP is now service-oriented, which tends to solve for smoother economic cycles. Cutting rates in a weakening but still growing economy, where inflation hovers above the Fed’s target, is risky business and may lead investors to demand higher long-term interest rates.

Risk three: tariff income might be deemed illegal

The president used a 1977 emergency law to impose tariffs on goods from over 100 countries. On the back of that, tariff revenues have grown for months, and the latest data shows that the US has collected $223.9 billion from them as of 31st October which is $142.2 billion more than the same time last year. This month, the US Supreme Court began hearing cases that could rule certain tariffs and their corresponding revenue streams illegal. These developments could worsen the US fiscal situation and bring the fiscal challenge back into the limelight, likely leading to higher term premium. I consider this likely to be a short term impact, as the Trump administration will probably find new ways to enact tariffs.

Risk four: shift away from T-Bill heavy funding profile

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has signalled a preference to avoid locking the government into higher borrowing costs when bills are cheaper. Just a few days ago the US Treasury confirmed this by indicating in its quarterly refinancing statement that it does not plan to increase sales of notes and bonds until well into next year and will rely more heavily on bills, which mature in up to one year, to fund the budget deficit. T-bills currently comprise 20% of the US debt held by the public. The Treasury has acknowledged that this reliance reduces expected costs while also increasing volatility of its funding profile. This trade-off is highly sensitive to baseline economic forecasts. While the current funding mix is appropriate in a “productivity boom” scenario, other scenarios highlight additional risks. Interestingly, their model suggests that a reduction in bill issuance in favour of mid-duration issuance could lower volatility for a negligible increase in costs in adverse scenarios. Thus, the odds of a shift away from a T-bill-heavy funding profile might be higher than many believe.

While the positive real yields offered by long-dated US Treasuries are tempting, we await the resolution of some of the uncertainties discussed to strengthen our conviction. For now, we consider positive real yields more attractive in other market areas where we have greater confidence in the direction of long-dated yields.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.