This year has seen the sharpest and largest economic downturn the modern global economy has ever seen. However, as I have commented several times this year, this recession is a rather strange one: for once, this time really is different (see chart below).

This recession has not been caused by any of the usual suspects: namely tight financial conditions, a real or market bubble bursting, a sharp rise in commodity prices or some combination of these. We have not seen the effect of this recession in many of the typical areas of weakness that follow such a downturn: I’m thinking of everything from the housing market and disposable incomes, to the huge rally in financial asset prices we have seen this year. Finally, this year has pushed investors to accept more than ever the bizarre situation of paying for the privilege of lending out their money — testing the zero bound in interest rates and leading to some very strange consequences indeed.

As we sit at this zero bound, I believe there are some important consequences for investors, ranging from the purpose of investing to the independence of central banks.

The theory of investing

The cornerstone of saving is security and return. In the following Panoramic we are going to focus on risk-free bond returns, and particularly on the strange consequences we see when this asset class has a negative return.

When buying a bond, you receive a set of cashflows in return for your investment. This is illustrated simply below.

This shows the income you receive and the final redemption payment. This income stream in the theoretical example generates a positive yield – the sum of the cash flows earned is positive. This is the fundamental basis of bond investing. However, recently this cashflow dynamic has been spun round. The actual example shows the cashflows you receive as a result of your investment in a negative-yielding bond, as we see in German bunds, for example. The cashflows earned are negative and the investor ends up with less money than originally invested.

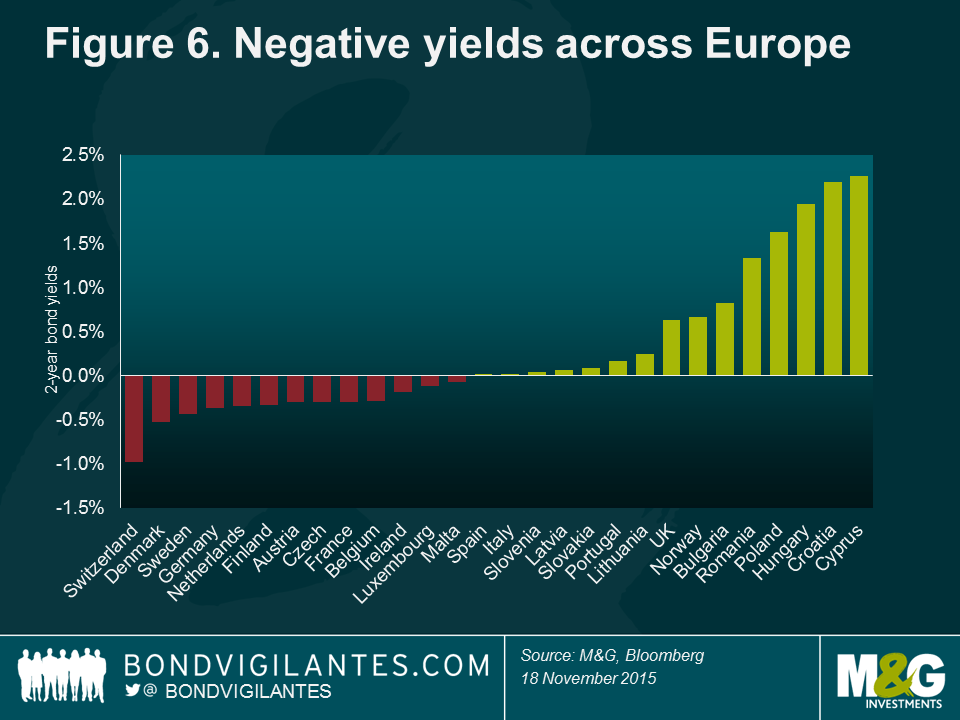

Positive-yielding bonds offer a positive total return if held to maturity. Negative-yielding bonds provide a negative total return if held to maturity. Economic textbooks show savers receiving income, and building their wealth. Meanwhile, borrowers pay income for the privilege of borrowing. Yet, in a negative yield world, the saver receives the negative cashflow of the borrower, and the borrower receives income for borrowing. This is a very strange world indeed! In the past, this would have been very much a theoretical exercise, but now it is a real-world phenomenon, which investors are accepting – see the amount of negative-yielding debt illustrated below. [1]

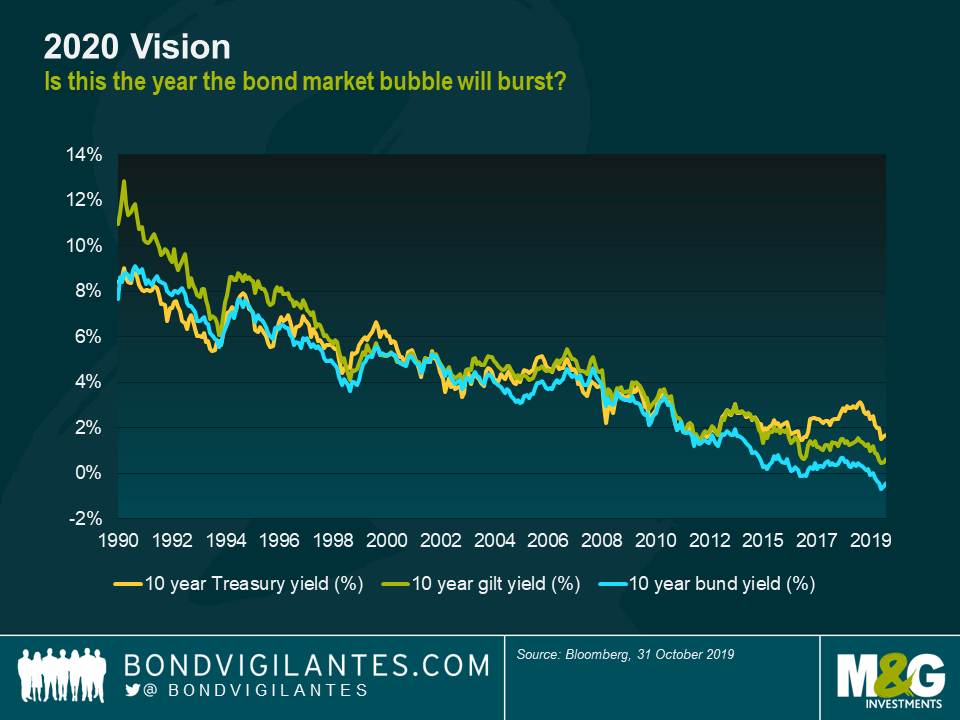

How did we get to this point? The bull market of the last cycle has driven bond yields to new lows, while many central banks have cut rates to try to stimulate inflation in economies. The question now is whether this downward trend can continue forever. I don’t think so: at some point, the consequences of having negative rates become too great for investors to accept. At this point we hit the “zero bound” – near zero, though not necessarily exactly at zero. The chart of 10-year rates below shows the trend over the last 30 years, with rates declining and halting at the zero bound. So why do rates stop at the “zero bound”?

Why there is a zero bound

Bond yields have difficulty going much below zero because if investors are faced with owning negative yielding debt in Japanese yen, for instance, they have an alternative. They can simply hold Japanese yen cash instead. Rather than exchanging 100 yen and receiving fewer yen at maturity if purchasing a bond, an individual could simply hold 100 yen in cash and not suffer the loss. Holding cash has its risks and potential costs in terms of security and storage. These costs effectively set where the zero bound falls, and why it is not exactly zero: it would be zero, were there no costs to holding cash instead of bonds. The presence of this alternative risk-free investment explains why central banks around the world have not enacted a significant negative rate policy: the existence of cash is the main barrier to negative rates.

The risk/reward of the zero bound – There Is No Yield (TINY)

Once we recognise there is a zero bound somewhere, what does that actually mean for bond investors?

When looking at the risk/reward of the zero bound, the first issue we face is that There Is No Yield (TINY). With yields at all-time lows, investors are not earning significant returns at all, while in some cases paying for the privilege of lending. Secondly, it is clear that yields can’t fall forever: the upside of holding duration is limited due to the existence of the zero bound. One way to explore this is to use zero coupon bonds to illustrate the risk and reward profile to which investors are exposed when buying bonds in the TINY world.

Currently, if you agree to buy a 30-year German bund at a negative yield, you essentially agree to make a loss if held to maturity. This is of course different from a positive interest rate environment, where if you hold the bond until maturity you will end up with a positive return. The profit or loss involved is illustrated in the chart below: if you buy a bond with a -2.3% yield, you lock in a halving of your money.

The upside to holding low- or negative-yielding bond securities is therefore very limited and explains the short duration view I express in my funds. When you hit the negative bound, or get near the negative bound, it becomes challenging to invest; upside is limited and losses can quickly accrue (even more so if you hold longer-term debt to maturity).

So while it is possible to get to negative interest rates in principle, it is rarer in practice, and there is a limit: the upside to investors is limited, but the downside could be quite large, and so at a certain point investors won’t accept this. This means it is hard to justify being long duration, from my perspective. As a risk-reward instrument, holding interest rate duration becomes unattractive when you get near the zero-bound. There are also other, wider consequences beyond the risk-reward of owning bonds as yields reach the zero bound.

Consequences of reaching the zero bound

One of the most obvious consequences of reaching the zero bound is that central banks can no longer stimulate the economy in the event of a deterioration in growth and demand. As rates cannot go very negative, the policy tool is effectively removed from their toolkit. This is illustrated by the actions of central banks in regions where rates were already negative or near zero, like Europe and Japan: the policy option has gone. We saw the effect on holders of interest rate duration over the past year: in countries where rates could still be cut (the US and the UK), falling interest rates provide some upside to bond investors; in countries with zero or near-zero rates (German and Japan), they did not provide much upside at all (see charts below).

Another effect of short-term zero or negative interest rates is the extent to which this undermines the banking system’s traditional role in bridging saver and lender. As former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King alluded to in a recent TV interview: “[Negative rates] can’t work with a successful banking sector unless the banks can pass on negative rates to their retail customers. Once that happens, I think you should expect to see a long line of customers seeking to take their cash out of the bank and keep it under the mattress, or at least in a new home safe. I don’t think that is a politically attractive prospect at all”. [2]

It is clear that having zero or negative rates is a threat to the ability of central banks to use monetary policy and to the banking system’s effective functioning.

Unable to cut rates, central banks then pursue other options, resulting mainly in driving rates lower along the yield curve via measures such as forward guidance (i.e. pre-committing policy to a low rate range) and quantitative easing. These actions lower rates along the whole yield curve, flattening it by pushing longer-term rates towards the zero bound too. This can be seen in the chart below of the market 50-year sterling overnight lending rate: it reached the zero bound.

Likewise, the psychology of investors not wanting to lock in a guaranteed loss leads them to extend the maturity of their investment, again pushing the whole curve towards the zero bound. Investors’ purchases of longer-dated bonds result in very flat yield curves as can be seen below. This effect is so powerful that in extremis whole bond curves can exhibit negative yields (see chart below).

As monetary policy reaches its limits, fiscal policy has to take a greater burden in reviving the economy. Consider the recent comments from Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell, and European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde. Both central bank chiefs have called on extended fiscal support to boost Covid-hit economies as we approach a tough winter. Powell said that “too little support would lead to a weak recovery, creating unnecessary hardship for households and businesses”, while stating that even if stimulus is above what is needed “it will not go to waste”. Meanwhile, Lagarde emphasised that it is “more important than ever for monetary policy and fiscal policy to keep working hand in hand”.[3]

Interest rates are a pricing mechanism that set a level at which savers and borrowers can interact, and provide an efficient recycling of savings. Between these two economic agents, we have a banking system that recycles that capital. These banks make money on the bid- offer spread between borrowing and lending, but are also heavily dependent on the central bank for help. When the central bank sets a high rate, it is guaranteeing savers and banks a high return for taking no risk – in effect offering a subsidy and a transfer of wealth from the state to the saver. In an environment of negative rates, the central bank is instead taxing the financial system, and savers will be reluctant to lend. In that case, the recycling of capital grinds to a halt.

How to remove the zero bound

The simplest way to remove the zero bound and restore the ability of central banks to cut rates would be to remove the option of holding cash. Electronic money is a solution as, if there were no cash, then your electronic money deposit could decay over time, producing negative rates with no alternative cash to hand. Politically, though, this would be highly unpopular for various, obvious reasons – and individuals may see this as a tax on capital. Other alternatives to money might also be sought, which would undermine this approach: gold, a foreign currency or a different version of electronic money such as Bitcoin are examples.

The second way would be to let the central bank lend money below zero to subsidise the banks. That is the ECB’s approach with its TLTRO (targeted longer-term refinancing operations) programme, designed to stimulate lending and act as a simple subsidy from the central bank to private sector banks. However, this is an intrinsically loss-making transaction by the central banks and ultimately has limited power, because it creates an arbitrage opportunity between negative rates and physical cash.

The third option is to print money. This is perhaps the simplest way to escape the zero bound, but unfortunately raises the difficult question: who do you give the printed money to? Central banks are in the business of lending money, not granting money. As Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said in his May keynote speech, “the Fed has lending powers, not spending powers”. [4]

The printing of money is a government decision

To escape the zero bound requires a number of key elements. It would require the support of governments through fiscal spending, the printing of money by the central bank and hopefully a pick-up in inflation. But this requires central banks and governments to work together. Fiscal spending is within the remit of government and, if the central bank is printing money, the decision on how that money is distributed is a political one. Central banks and governments have to work together.

No Independent Central (NICe) Banks

The ultimate way to do this, for fiscal and monetary policy to be aligned, would be to remove central bank independence. Arguably we have begun to see signs of this over the past year, with the significant government debt purchases of a number of central banks. Independent central banks were created in the first place to help control inflation and I would argue that, in politicising central banks, we would be allowing the inflation genie back out of the bottle. In order to escape the zero bound we need inflation, and by politicising central banks inflation and inflation expectations would rise.

It would be easier to remove the independence of some central banks than others, of course. The simple delineation here is federal central banks versus state central banks. It would be relatively straightforward to regain full control of the Bank of England, for example – in fact, it is already provided for under existing legislation: according to the Bank of England Act 1998, “the Treasury is given reserve powers to give orders to the Bank in the field of monetary policy, but the Act states that this is only if the Treasury is satisfied that they are required in the public interest and by ‘extreme economic circumstances’.” [5]

In the case of federal central banks it is more complicated. With federal central banks, monetary and fiscal policy are generally harder to carry out in tandem, as typified by the challenges faced by the European Central Bank.

The future of central banks

Central banks are an ever-evolving beast. Their need for independence was born in the high inflation conditions of the 1970s. This regime has worked exceptionally well in reducing inflation to the targets that have been set. If we now have a situation where inflation is permanently anchored around a two percent target then, by definition, central banks will quite likely be faced with the zero bound issue. The tapering of political influence on monetary policy has also helped reduce inflation, and this has been combined with the tailwind of falling inflation from globalisation and progress in technological productivity.

While central banks cherish their independence, they have been exceptionally vocal recently that fiscal measures (that are inherently political) are required. The gap between politics and central banking has been further eroded as central banks are now opining and focusing on what were previously political issues. For example they are now focusing more on income inequality and the global warming conversation — both historically hot political topics and not the remit of unelected central bankers. With these issues in mind, it may be practical for central banks to become less independent, and the political bias to generate inflation may be an appropriate change in economic direction.

Implications for investors

Given the authorities are going to do what they can to exit the zero bound, what are the implications for investors? It would be logical to assume that escaping the zero bound would require extensive monetary and fiscal policy. This would mean short rates being kept low for a number of years, while inflation needs to be re-established as a permanent feature. This points potentially to a very steep yield curve, with short rates pegged, a heavy supply of government debt, and inflation making real bond returns less attractive. It is likely that this high level of monetary and fiscal stimulus will be a strong boost for the global economy. What kind of traction will it provide in 2021 and beyond?

Outlook and concluding thoughts

The world is going through a t-shaped recession: a sharp fall down, with a recovery back towards previous levels. The question is how high up the “t” the crossbar gets. Given that the service sector has been the main victim of the lockdown recession and government action, the ability to reopen quickly may mean at the extreme that we even get close to a T-shaped recession. The lower the bounce, the better for interest rate risk and the worse for credit risk, and vice versa. This is why the economic outlook is so significant in bond investing. However, the risk-reward profile of taking interest rate duration is currently skewed: there is limited upside on profiting from further falls in interest rates if the zero bound persists. This has been demonstrated in the real world of bond investing this year.

There is a need to escape the zero bound for micro and macro policy reasons. This will require central banks to be more “NICe” as they work closely with governments. In such a scenario, fiscal and monetary policy will need to remain loose for some while, potentially aided by central banks printing money to provide the fuel to escape the zero bound. This type of policy generally leads to higher growth and inflation. This bodes well for the economy and for credit risk, but points to a rise in longer-term bond yields.

[1] When looking at total negative rates, one should bear in mind that rates are defined as the rate in a given currency. If we were to hedge global debt into a base currency of euros for example, the negative outstanding debt would be boosted; if it were turned into US dollars, it would be reduced substantially.

[2] Mervyn King, Bloomberg TV, 16/11/20.

[3] https://www.marketwatch.com/story/powell-says-u-s-economy-needs-more-fiscal-support-11601995205, https://uk.finance.yahoo.com/news/lagarde-pledges-forceful-ecb-stimulus-082057866.html

[4] Current Economic Issues: Remarks by Jerome H. Powell, Chair, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System at Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington, D.C., May 13, 2020 https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/powell20200513a.htm

[5] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/1998/the-boe-act.pdf

Let me start with two predictions. Firstly that the title “2020 Vision” will be irresistible to all year-ahead outlooks, no matter what publication or industry you work in. This is why I trademarked the idea many months ago, and now expect to retire on the proceeds of all the copyright breaches. My second prediction is that in my industry, bond fortune telling, virtually all of those 2020 outlook pieces will declare that it will be the year that the “bond bubble” bursts. Maybe they’ll be right this year, after a 30-year streak of “sell bonds” predictions. But their track record doesn’t suggest they have an edge in the bubble popping business.

If you do believe that 2020 is the year for bond bears finally to triumph, I think you have to believe that a lot of very long term, established trends are about to come to an end simultaneously. These trends are the Secular Seven. If you think that their powers are at an end, or significantly diminished, then you should join the January anti-bond mob with their pitchforks and flaming torches. Otherwise you’ll probably want to wait to see a conclusive break in the 30-year downtrend in bond yields and inflation before saying goodbye to fixed income.

The Secular Seven

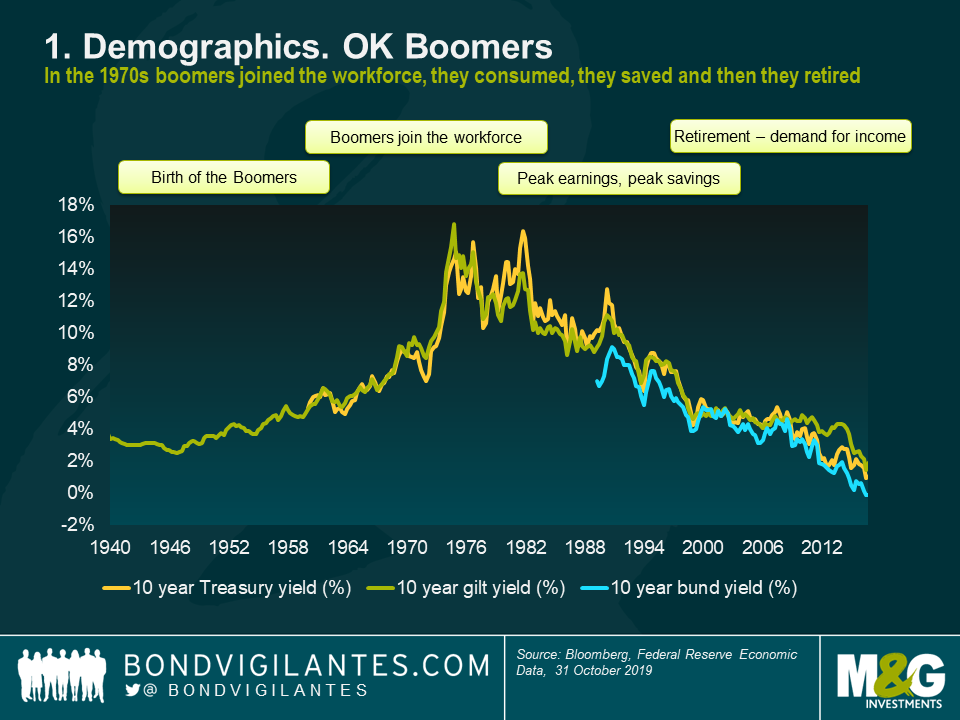

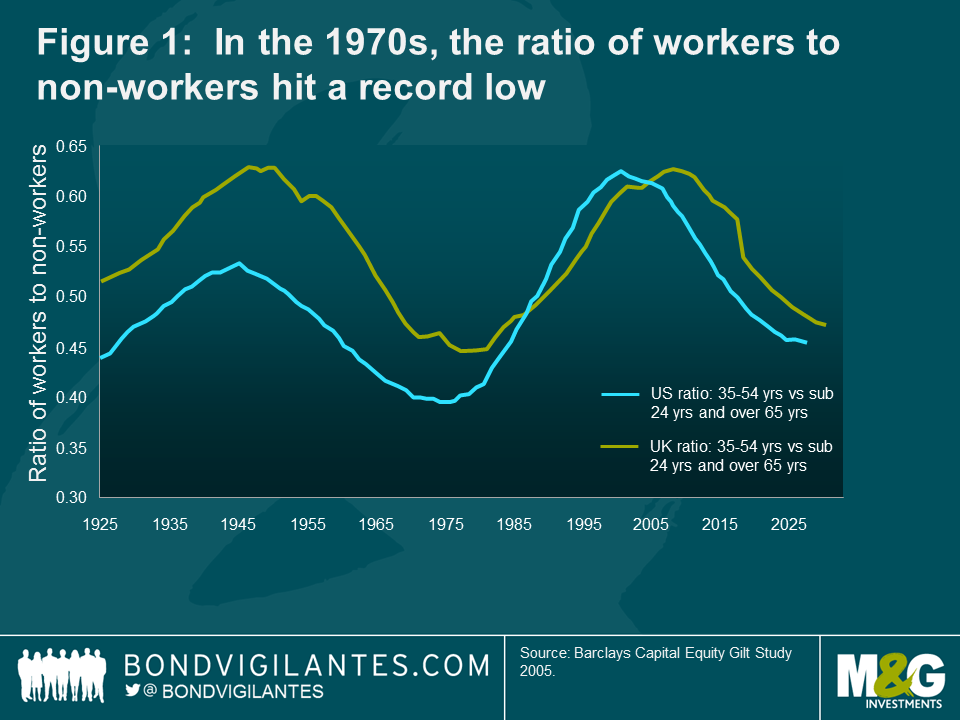

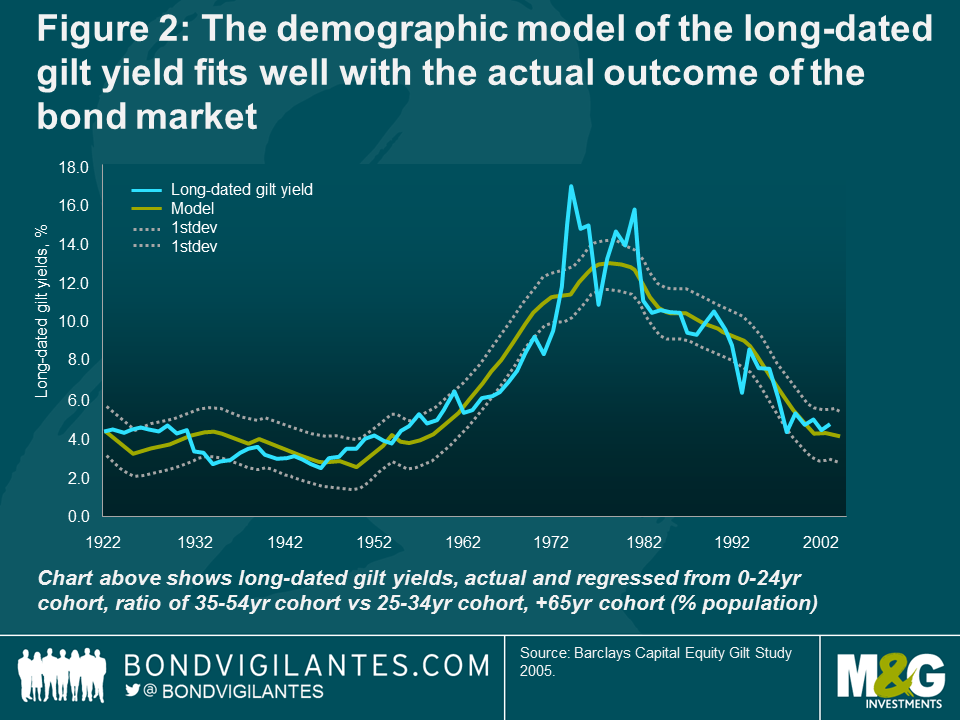

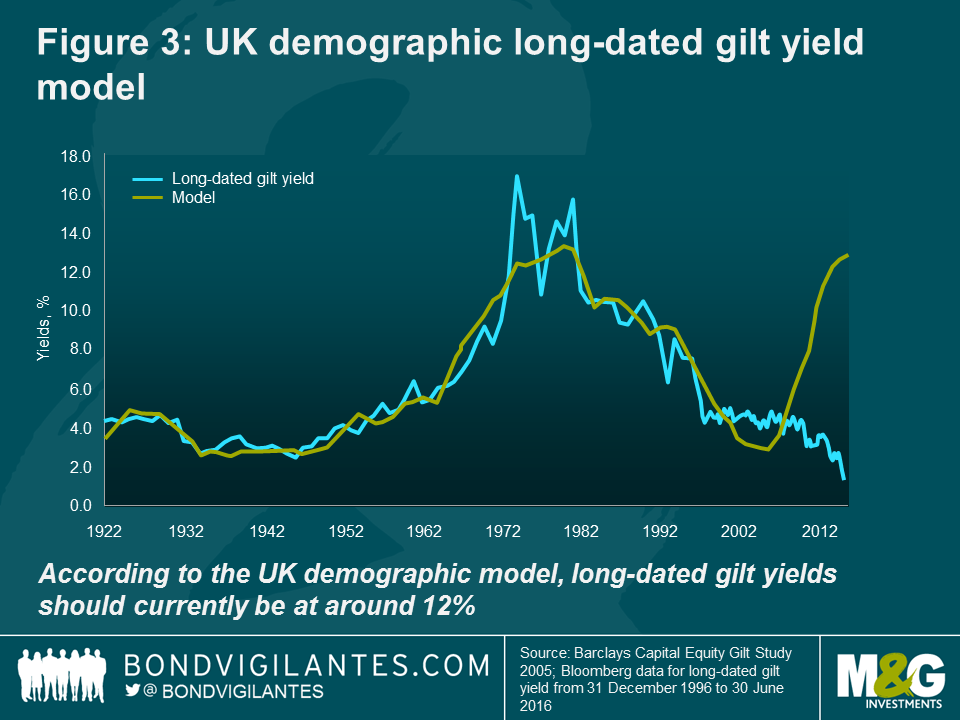

1 – Demographics. OK Boomers. The post-World War 2 baby boom impact on the economics of the developed economies can’t be overstated. In the 1970s and onwards as the Boomers left education and came to dominate the workforce, the labour scarcity that had been a feature of the western economies for a couple of decades started to come to an end. Trade Unions lost their membership and their power, and wage inflation dropped. Economies became more productive, and wealthier. With largely young and healthy populations, pressures on the welfare state (for example pension burdens, and care and healthcare costs for the elderly) were relatively subdued. As the demographic basketball (the Boomers) passed through the snake and reached peak earnings, their desire to save and invest those savings also hit new highs. Demand for income and safe assets grew dramatically – driving bond yields down.

2 – Technology’s impact on inflation. Why can’t we generate consumer or producer price inflation in developed economies despite zero or negative interest rates, “money printing” and periods of growth and low unemployment in the past decade which historically might have generated CPI of at least twice the current common inflation targets of 2%? The dramatic deflation in consumer goods is one answer, and a good part of that has been driven by the collapse in the price of technology. The 1996 Motorola StarTAC mobile phone cost $1000 then; a similar level phone today is about $200. 1996 was probably also the year I stopped hiring a TV (paying monthly) from Radio Rentals and bought one, as they’d become affordable. And it’s not just the cost of the hardware: I used to spend at least £50 a month on music on compact discs (and cassettes before that, which I note are now fashionable with youngsters). Now I pay £12.99 a month for all the music in the world on Spotify. Think also of all the free stuff that the internet provides, from maps to encyclopaedias and news, and perhaps the impact of low inflation is actually understated. The transparency of the internet also allows me to find the cheapest thing in the world whenever I buy something. Awful news for high street retailers, but the deliverer of a huge consumer surplus and disinflation. Finally, we haven’t even discussed the Rise of the Robots yet: what if AI and robotics are finally deployed in the workforce on a massive scale? What does that do to wages? To employment and disposable income? It certainly sounds like a further technological leg down in price inflation is possible.

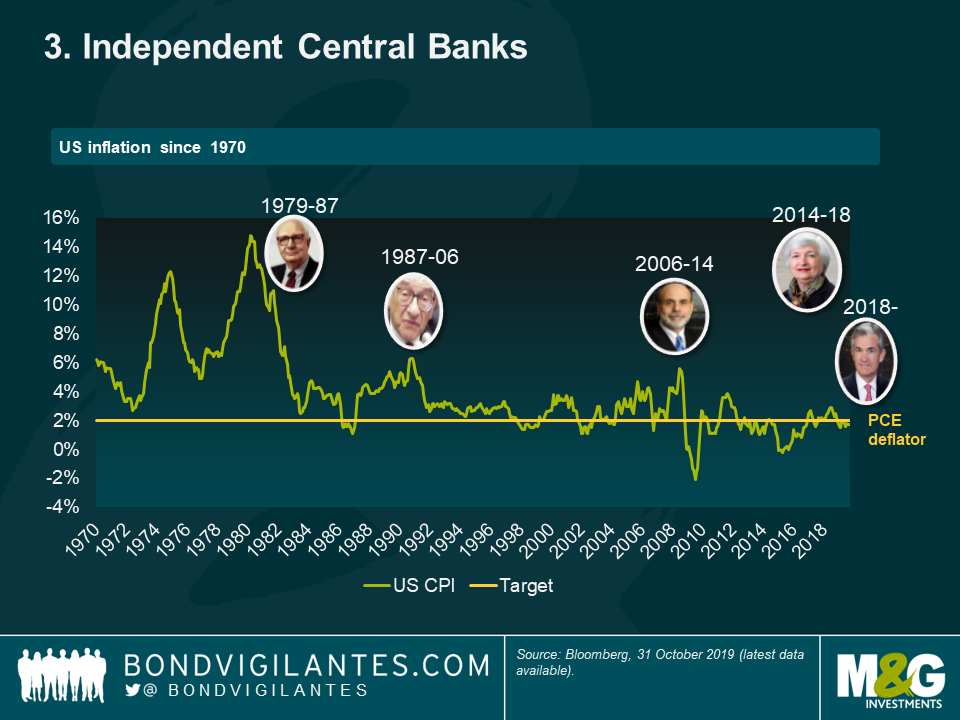

3 – Independent Central Banks. When Paul Volker was appointed Chair of the US Federal Reserve Bank in 1979, inflation in the States was 11.3%, peaking in March 1980 at 14.3%. US Treasury Bonds were thought to be almost uninvestable as yields were eroded by the rise in the cost of living. Volker set the Fed Funds rate above the rate of inflation – at the time a radical idea. Inflation fell steadily through his tenure, and an “inflation fighting central bank” culture was established. This led to explicit inflation targeting around the world, from New Zealand through to Gordon Brown making the Bank of England independent, and on to an ECB which was so wedded to this inflation-fighting mandate that its President, Trichet, hiked rates twice in the midst of the Global Financial Crisis on the grounds that oil prices had risen year on year and had taken eurozone CPI above 2%. Central bankers have certainly taken a lot of the credit for the bond friendly environment we’ve been in for the past couple of decades, but it’s clear that this separation of their powers from elected politicians coincided with some arguably more powerful trends.

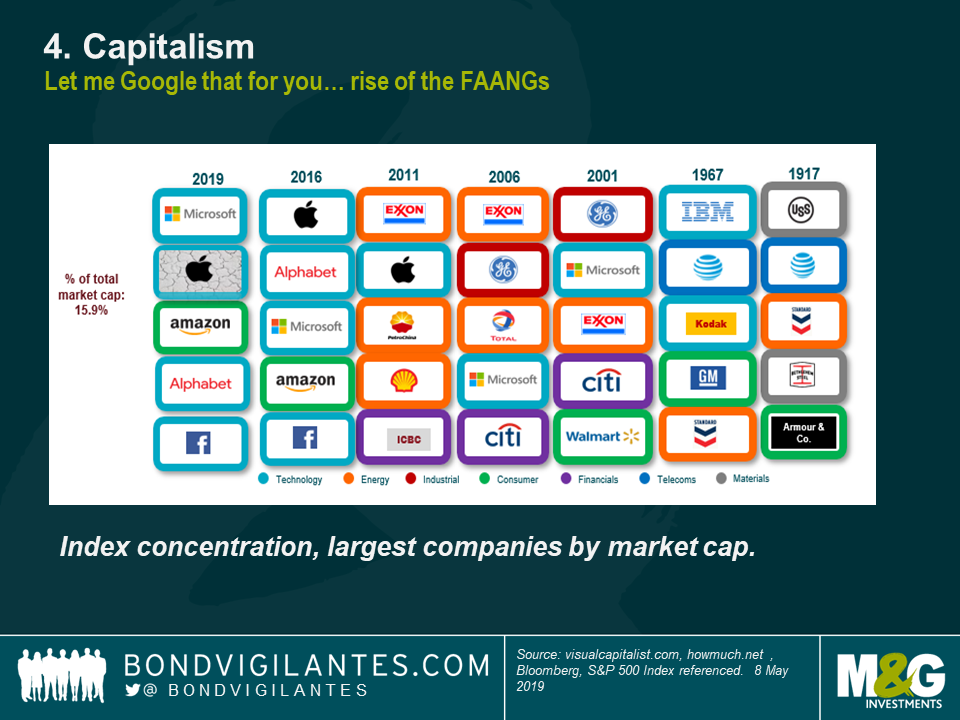

4 – Capitalism. As labour has become less powerful since the entry of the Boomers into the economy, capital gained the upper hand and has taken the bigger share of profits and growth in developed economies for years now. Governments have deregulated financial markets and labour markets (with some notable exceptions like the introduction of the Minimum Wage in the UK), and the emergence of the new tech giants (the FAANGs) has led to both increased competition in some areas (Amazon has delivered massive consumer surplus in its race to acquire market dominance) and monopoly creation in others (Google is a verb as well as an online advertising giant). Capitalism has thus kept wage growth low, and encouraged the growth of a tenuous gig economy landscape. Whilst there are examples of monopolies developing, as the land-grab continues, prices have stayed low. Take a look at some of the bloggers in the US who write about existing on free trial subscriptions (everything from mattresses to groceries) and half price food delivery offers as companies try to buy some market share. I’ve got a 50% off Uber Eats trial in my inbox right now. Burger or pizza?

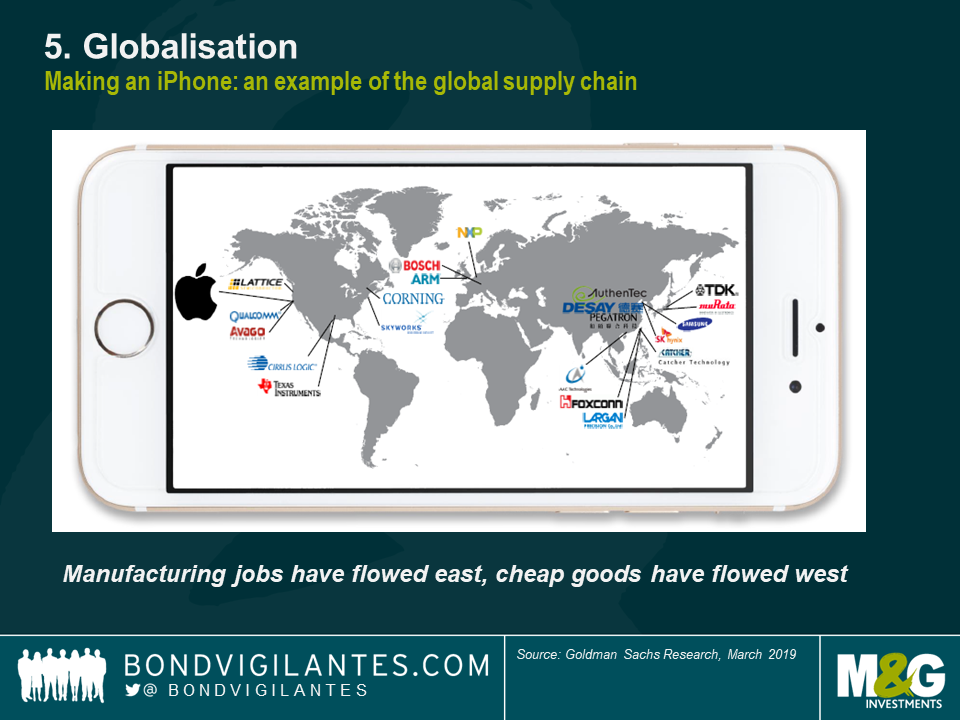

5 – Globalisation. China joining the World Trade Organisation in 2001 didn’t start the process of globalisation, but it did signal that everything had changed, especially for manufacturing companies. The supply chain became a global one, and goods prices collapsed as we all imported cheap stuff made by people earning fractions of western wages. The liberalisation of trade barriers and tariffs, together with advances in the logistics and cost of containerisation and shipping, meant that manufacturing jobs went east and cheap goods flowed west.

6 – The Austerity Meme. I’ve been fascinated by the Reinhart & Rogoff “This Time is Different” book ever since it came out. Flawed in some of its initial calculations, its narrative of higher government borrowing leading to economic disaster nevertheless set the scene for a decade of austerity in many of the economies hit hardest by the Global Financial Crisis. Now the relationship between government borrowing, bond issuance and bond yields is surprisingly weak: you’d think that as governments issued more bonds, prices would fall. This turns out not be true historically, as times when governments borrow more have usually been those times when growth and inflation are weak. Nevertheless, the UK for example has seen relatively low bond issuance since the GFC as the result of the longest period of austerity recorded. Germany is running a budget surplus, despite stagnant eurozone growth. It’s therefore possible that this period of relatively low bond issuance at a time of weak growth has delivered lower bond yields than we’d have normally had.

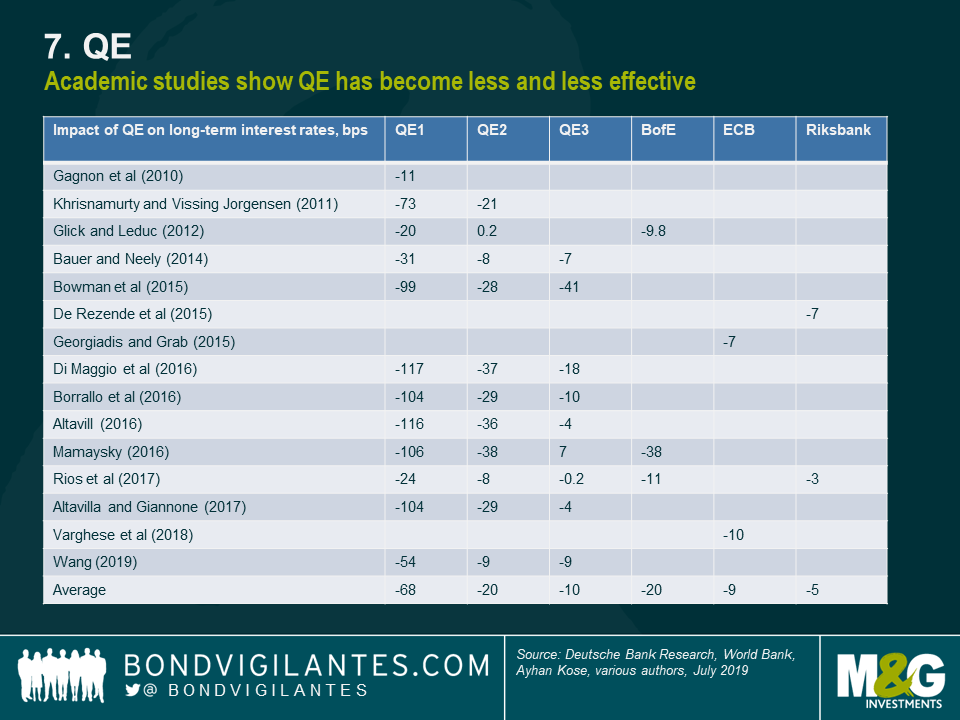

7 – QE. We’ve had 3 rounds of Quantitative Easing from the Fed since the GFC. The Bank of England has also bought both gilts and corporate bonds. The Bank of Japan and the ECB have also massively expanded their balance sheets in bond purchase programmes. And the ECB has just announced endless QE in Mario Draghi’s parting policy announcement. Does QE reduce bond yields? Yes. A study of all the academic papers on the impact of QE around the world showed that on average the three rounds of US QE reduced US Treasury Bond yields by about 70 bps, 20 bps, and 10 bps respectively. Whilst inflation remains below target in most of the developed economies, it’s unlikely that we see any unwinding of the bonds held on central banks’ balance sheets – in fact some of us think that these bonds will never be set back into the wild, and will mature in the dark of those central bank vaults.

So are any of the Secular Seven under threat?

Yes. Many of them look to be less powerful than they were at their peak, although it’s possible that we’ve only so far seen the first stages of technology’s impact on wages and inflation: companies are sitting on cash piles that will be invested in productive technology at the first sign that their flesh and blood robots are achieving higher wages. An example of this in action was the introduction of self-service ordering systems in fast food restaurants after minimum wage increases for workers in those US businesses.

Demographic trends remain in place, although the never ending increases in life expectancy that we’d come to expect have stalled in some demographics, thanks to obesity related illnesses and opioid addiction. There are also some stark differences across the developed world, with birth rates in the US much higher than in parts of Europe, implying higher potential growth rates in America in the future. Japan shows us that even when labour force growth peaks and declines (Japan is a decade ahead of the west demographically), this isn’t enough on its own to combat entrenched deflationary forces.

Have we had enough of independent central banks? Donald Trump certainly has if you read his tweets over the past year. Fed Chair Jay Powell has come under immense pressure to cut rates towards zero again, and if Trump is re-elected in 2020 you have to imagine that Powell is replaced by someone more willing to turbo charge the US economy. In the UK, Mark Carney remains as the Bank of England Governor for the time being, but you could imagine some post-election outcomes that deliver some partisan choices as his replacement. Incidentally, the Bank of England just announced it is changing the title of its Inflation Report. It will now be the Monetary Policy Report which, if Sod’s Law has its way, will mark the return of rampant price rises. Central banks took the credit for the collapse in inflation over the past thirty years – and as I’ve discussed they were just one smallish part of that story – so they shouldn’t be surprised to take the blame now that inflation is too low for comfort, and this will undoubtedly threaten their mandates.

Whether capitalism’s dominance of the economic system continues to the same extent rather depends on a couple of rather important election results. On the electoral front, whilst neither candidate is a bookmaker’s favourite to take office, both Jeremy Corbyn in the UK and Elizabeth Warren in the US have a chance of power, and both have radical agendas which would likely involve higher rates of corporation tax, wealth taxes, financial transaction taxes and higher government spending. Monopolies in the tech space could be broken up, and financial regulation could tighten once more. Nationalisation of some industries couldn’t be ruled out. After a period of right wing populism in the UK (Brexit) and US (MAGA), the pendulum might swing the other way, and the left could take its revenge. Coupled with existing protectionism movements in the US (the trade war with China could be cooling, but has already damaged the global economy) and new European trade barriers post-Brexit, the left’s anti-globalisation philosophy (on the grounds that it produces a race to the bottom in workers’ rights) could exacerbate the stalling on global trade flows.

We go into 2020 then with some of the tailwinds for falling bond yields having been diminished, and one in particular – that of the austerity meme – likely to have turned into a headwind, with some potentially large increases in government borrowing in prospect. Also importantly, our starting valuations for “risk free” assets are unattractive, with most developed market government bonds having negative real yields. I don’t believe that a negative real yield is in itself an aberration, and we should come to regard the elevated real yields of the 1980s as the exception rather than the rule (you could get RPI plus 4% when you invested in index-linked gilts for a time), but clearly government bonds are expensive historically.

All of this means that I too will end 2019 with an underweight view on government bonds, expecting yields to move higher next year. But on any significant move up in bond yields, I’d want to buy back my gilts, bunds, Treasuries and JGBs, as many of the Secular Seven trends remain powerful, and there are clearly significant economic and social fragilities in the global system that could trigger further central bank policy moves – both traditional (rate cuts) and extraordinary (rate cuts below zero, more QE) – and a new flight to quality. We ain’t out of the shadow of the GFC just yet, and with more debt in the global system than there was in 2007, rising bond yields themselves could trigger the next big downturn.

Finally, remember that the global government bond market sets the “risk free” rate which is the major input in the valuation of all asset prices – from corporate bonds, to equity, to property. So if you are expecting a bond blood bath, the impact on other asset classes could be even more severe…

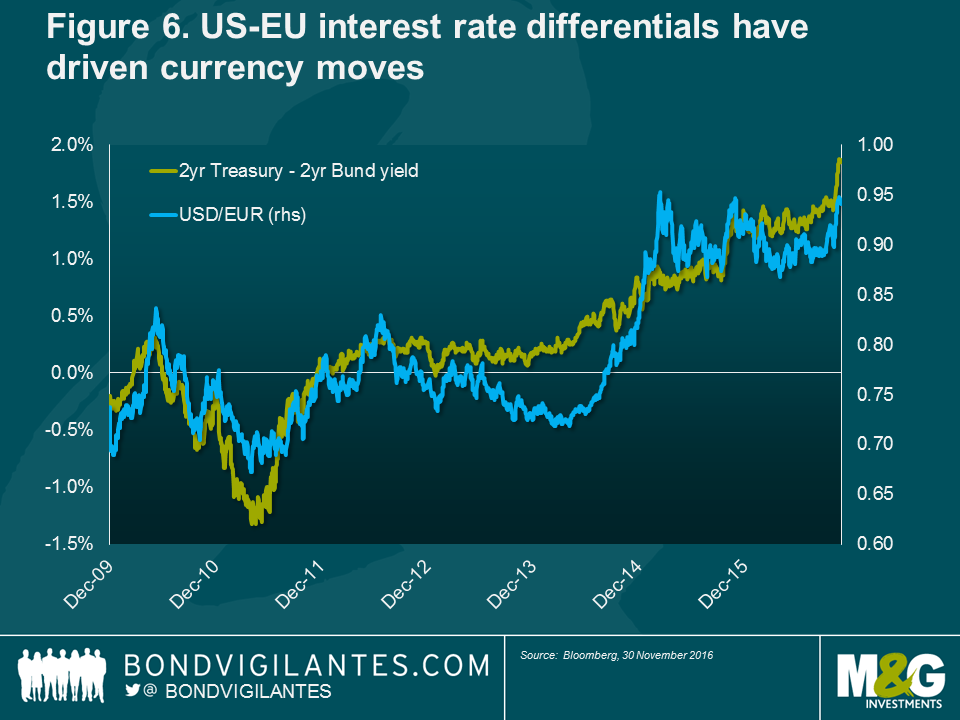

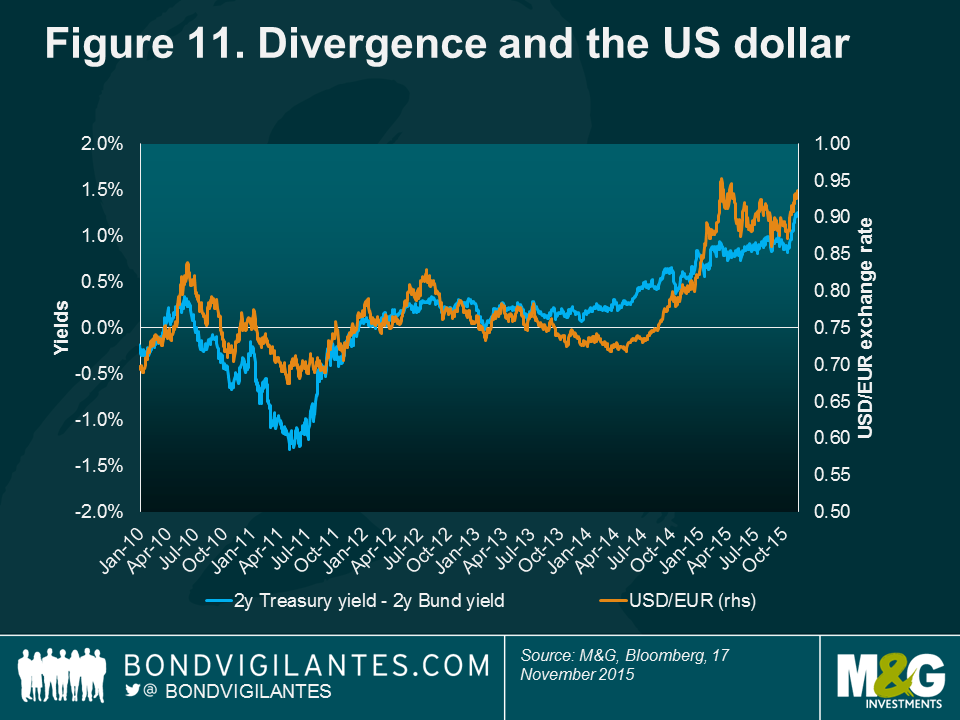

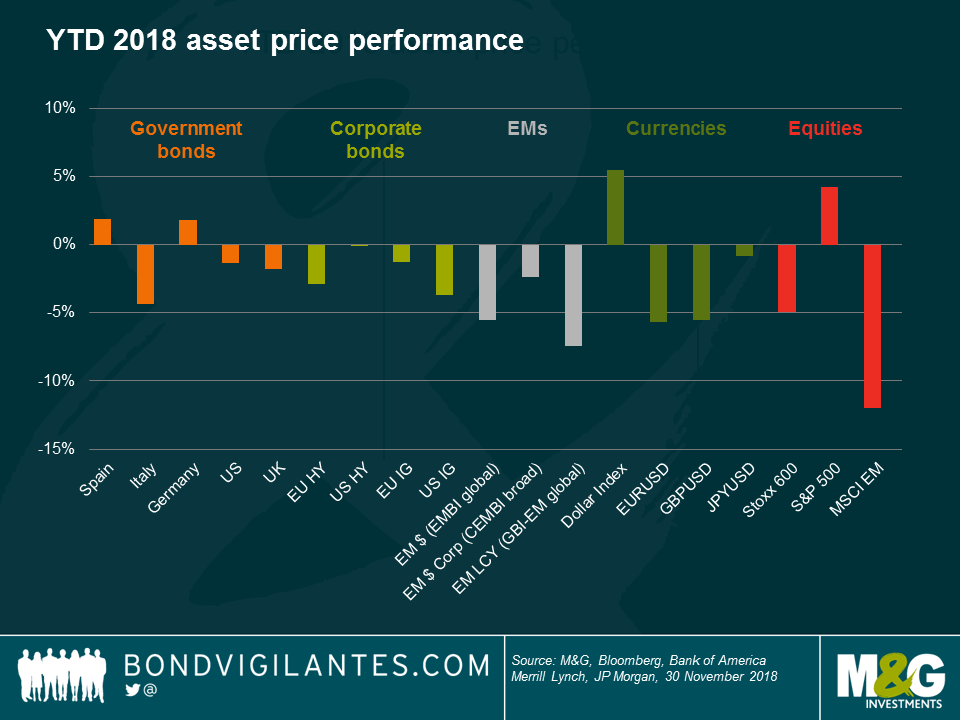

Whilst you can make some strong arguments for the negative returns from 90% of asset classes in 2018 based on the return of populist politics – think of Brexit, Italy’s political instability, AMLO’s election in Mexico and tariffs everywhere – the answer to those negative returns might be simpler: the de facto global discount rate, the 2-year US Treasury bond yield, has risen by almost 100 basis points (bps) over the year, and thus repriced global assets. Why did this happen?

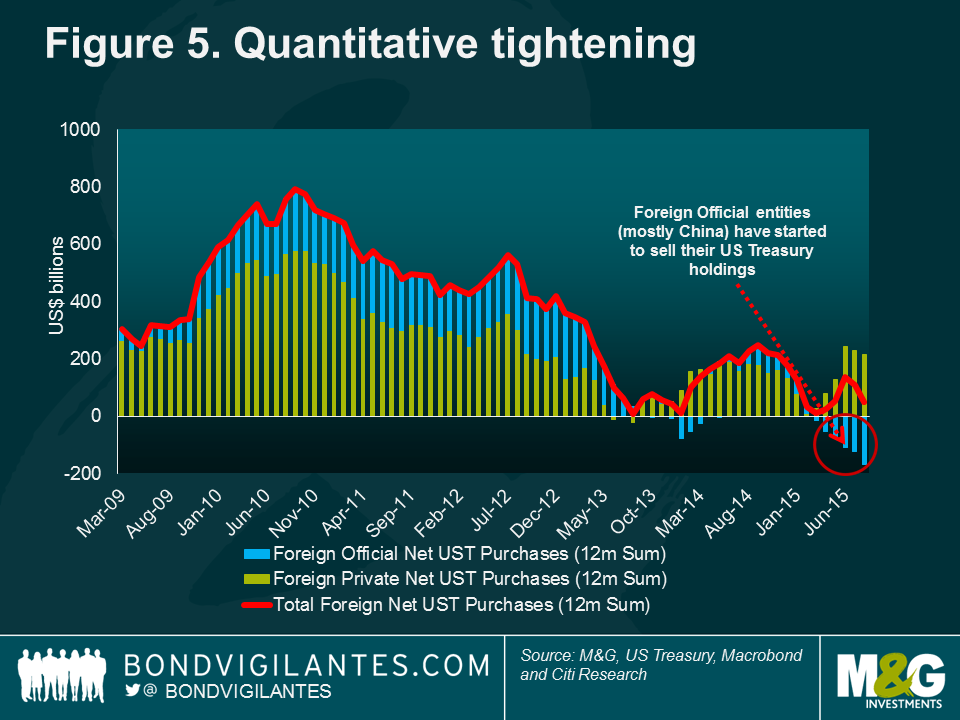

Well, 2018 was the year in which the global Quantitative Easing (QE) experiment started to come to an end. In the wake of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008 and the aftershock of the subsequent Eurozone Debt Crisis, central banks around the world started buying their own government bonds on a massive scale. The effectiveness of such programmes has been widely discussed, but most academic literature agrees that buying sovereign bonds brought down yields, creating a “portfolio rebalancing” effect that led investors to reach into riskier assets for income. In the UK, gilt investors sold their government bonds to the Bank of England and bought high quality corporate bonds instead; credit fund managers similarly added high yield bonds to their portfolios, while high yield investors moved down from BB to B rated debt. This led to a global inflation in asset prices, with the price of everything, from equities to art and fine wine, going up. The owners of such assets tended to be already wealthy, so inequality in society increased. Central banks regarded this as a known and necessary side effect, since inflation and economic growth also rose due to lower financing and debt servicing costs, benefiting everybody – but some argue that QE was a factor in the rise of political instability.

If you believe all this to be true, then you must also believe that when QE is reversed and becomes Quantitative Tightening (QT), then those portfolio effects should also turn. This year, we have already seen sovereign bond yields around the world starting to rise, helping risk-averse investors achieve their income targets without taking so much credit risk. This has led to the “yield tourists” in higher yielding asset classes starting to move back up the quality curve, pushing risk premia upwards, lifting borrowing costs and dragging down the price of risky assets.

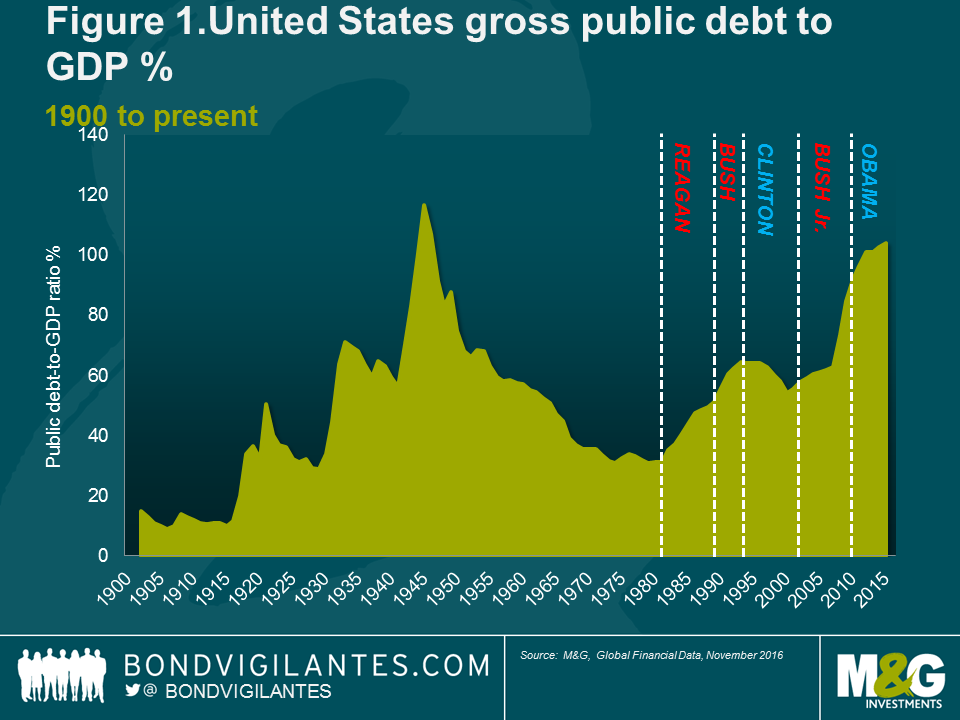

So far, QT has mainly been a feature of US monetary policy and the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet: the central bank’s holdings of US government bonds, mortgage-backed securities and other assets is expected to shrink to around $3 trillion in two years’ time, from a peak of over $4 trillion between 2015 and 2017. Whilst the Fed is not actively selling bonds, the absence of its market presence as an ongoing bond buyer is highly relevant, especially at a time when supply is only set to increase. US President Trump’s tax cuts and the ongoing increases in fiscal burdens caused by an ageing population mean that we will see budget deficits of well over $1 trillion per year for the foreseeable future. So, more bonds are coming to market, but the biggest buyer has gone.

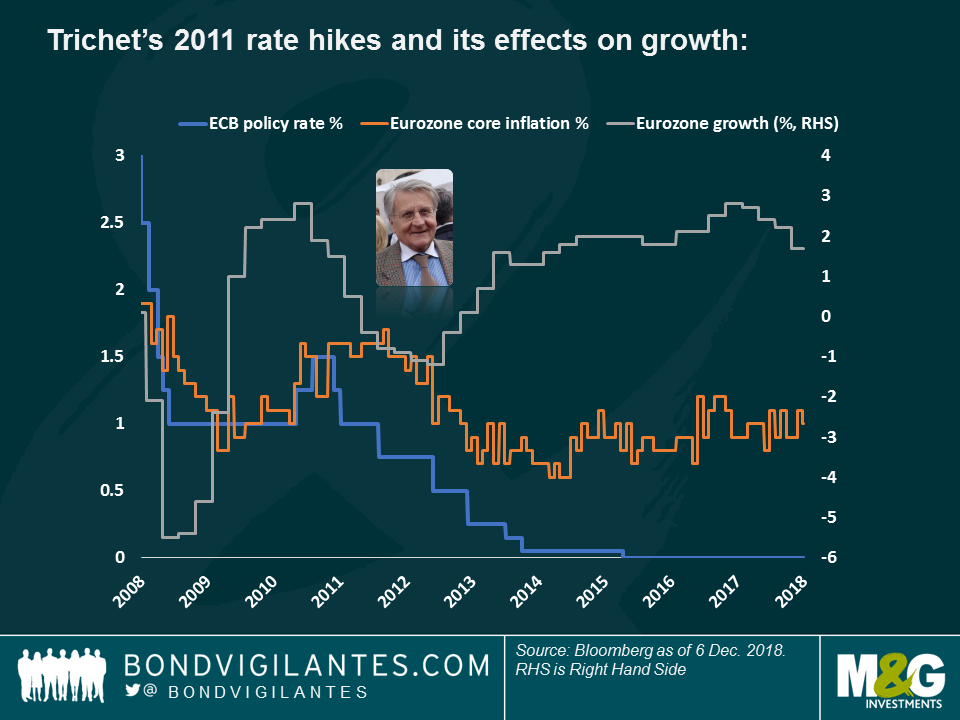

The European Central Bank (ECB) is also starting to exit QE, first by reducing its monthly bond purchases, and then by cutting them altogether by the end of this year. This is set to happen despite the turbulence in Italian bond markets (the BTP 10-year yield hit 3.68% in the final quarter of this year on fears over Italy’s future in the Eurozone and the country’s debt sustainability), and also despite a stubborn core inflation rate stuck at around 1%, well below the ECB’s 2% target. Could ECB President Mario Draghi be about to make the same mistake as his predecessor Jean-Claude Trichet in 2011, when he tightened monetary policy too early (blue line), putting brakes on a fragile economy (grey line) whose only inflationary pressures came from higher oil prices (orange)?

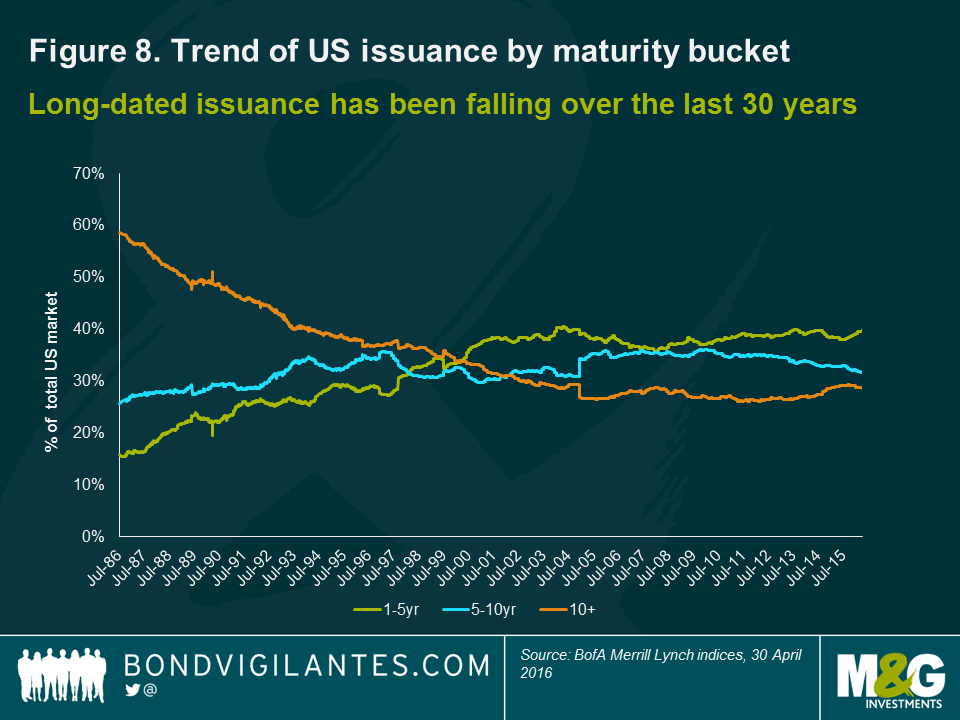

We fear Main Street may soon start feeling the QT pain, as Wall Street started doing so this year. But first, some good news: most corporate issuers took advantage of generationally low interest rates to borrow cheaply, and at long maturities. This means we don’t need to worry too much about an imminent “wall” of maturing corporate bonds, as companies have extended debt maturities, delaying the moment in which they seek capital to refinance their debt, typically at much higher interest costs. Also, according to Fed Chair Jerome Powell, rates may not be too far from their cycle highs.

“Interest rates are still low by historical standards, and they remain just below the broad range of estimates of the level that would be neutral for the economy,” – Jerome Powell, 28 Nov. 2018 (retracting from a month earlier assessment, in which he said that rates were “a long way from neutral.”)

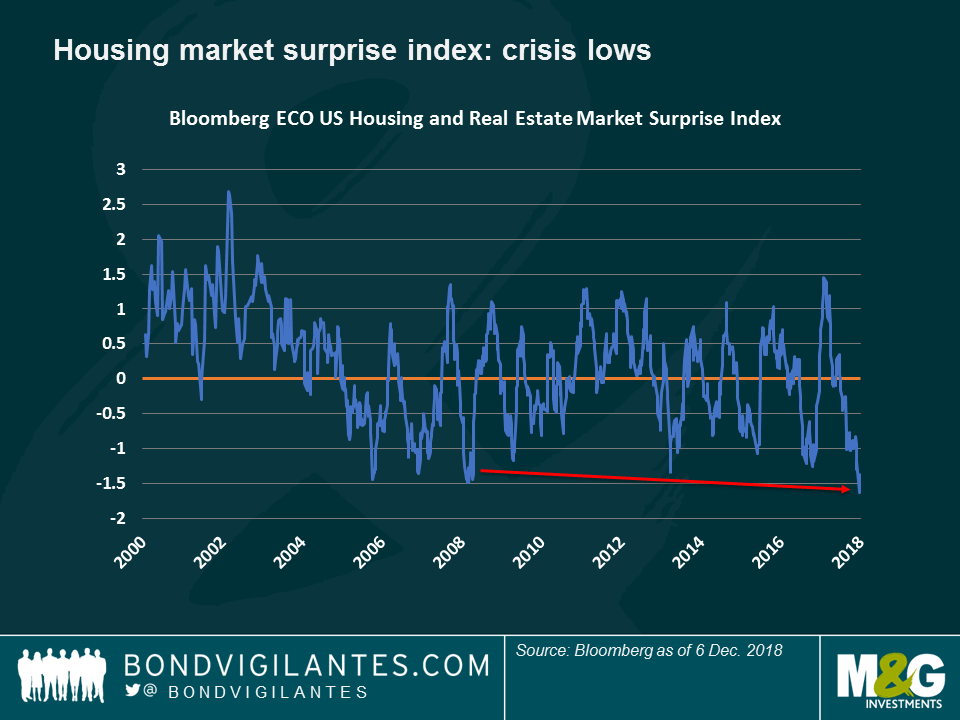

But higher rates do matter now (perhaps a factor in Powell’s rhetoric change): the US 30-year mortgage rate hit 4.8% recently, up from 3.3% in 2016. Whilst most existing homeowners, like corporates, will have locked in those cheap rates, new borrowers face costlier loans, and this is already having an impact: US housing and real estate data is surprising to the downside at a rate that exceeds that seen even in 2008 and 2009:

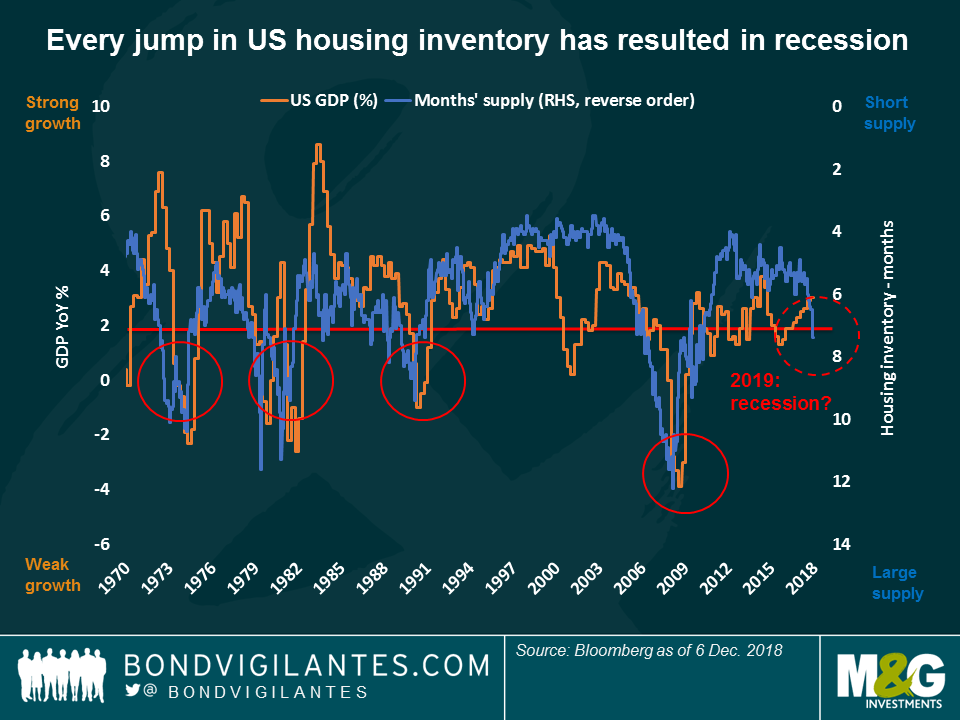

Housing is REALLY important to the economy. The “multiplier” effect of a house being built is significant as it is a labour-intensive industry; also, when you buy a house you also purchase white goods like fridges and freezers, TVs and furniture – and often a car (more on autos later). To assess the impact of the housing market on the economy, our favourite chart in 2007 showed the relationship between housing inventories (unsold new homes measured in months’ worth of supply) and US GDP growth. Whenever you saw the supply of unsold homes reach 7 months, a recession followed. It certainly did in 2008, despite the consensus of economic forecasters believing that economic growth would be 2.4% – it was actually negative. Why should we worry now? Well, the supply of unsold new homes is… 7.4 months (blue line).

As for autos, a bellwether of consumer confidence, the picture isn’t pretty, either. There are many reasons for global car sales to be falling: new emission standards, diesel scandals, tariffs, the rise of Uber/car sharing and the deferral of electric car purchases ahead of infrastructure upgrades. Still, the degree to which car sales is falling is shocking, at -10% per year. Reality is starting to bite: General Motors, for instance, recently announced US plant closures and nearly 15,000 job cuts.

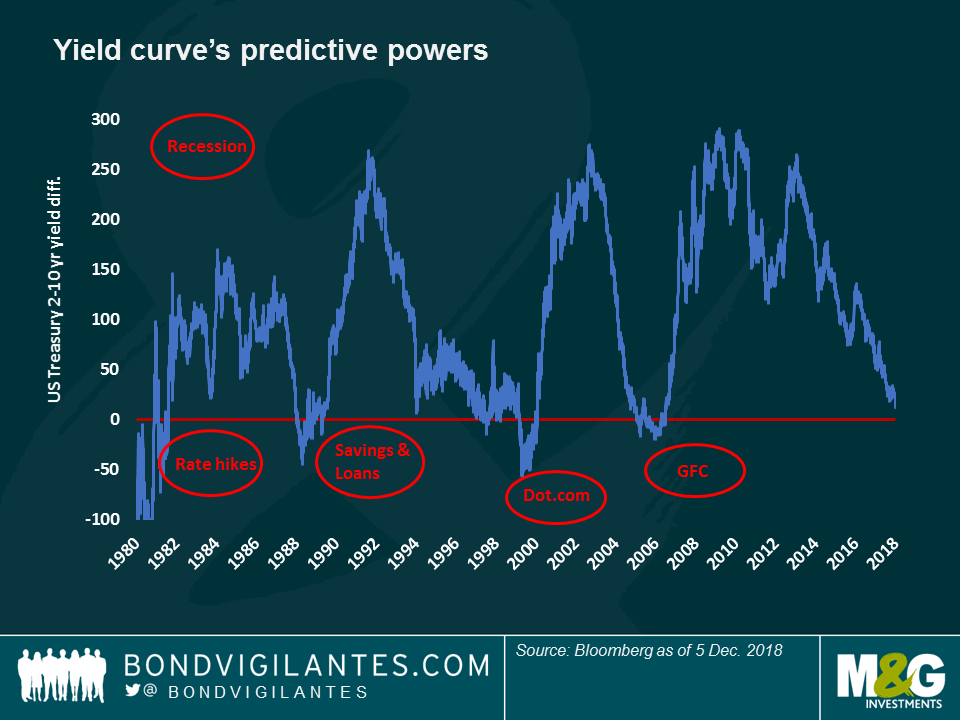

Reflecting this gloomy scenario, we have the one indicator that is really getting people worried: the shape of the yield curve. Traditionally, healthy-looking yield curves are upward sloping, with yields on long-dated bonds higher than those with short maturities, reflecting a premium for uncertainty (future inflation shocks or a fiscally irresponsible government, for example). But when the yield curve flattens and even inverts (with long bonds yielding less than shorter-dated ones), this is usually a harbinger of an economic slowdown as it reflects lower confidence in the future. In fact, there are virtually no incidences of an inversion not being followed by a recession, which in part explains why equity markets fell by 3% on December 4th, just as 5-year Treasury yields slipped below those at 2 years. When long-dated bonds yield less than short-dated ones, the bond market is predicting that interest rates will need to be cut by the central bank because recession is coming.

Are we therefore near the peak of the Fed hiking / tapering cycle? If so, you might think that 2018’s sell-off in almost all asset classes might be nearly over, and that there is value in both government bonds and credit. But for the latter there might be an economic slowdown to navigate first.

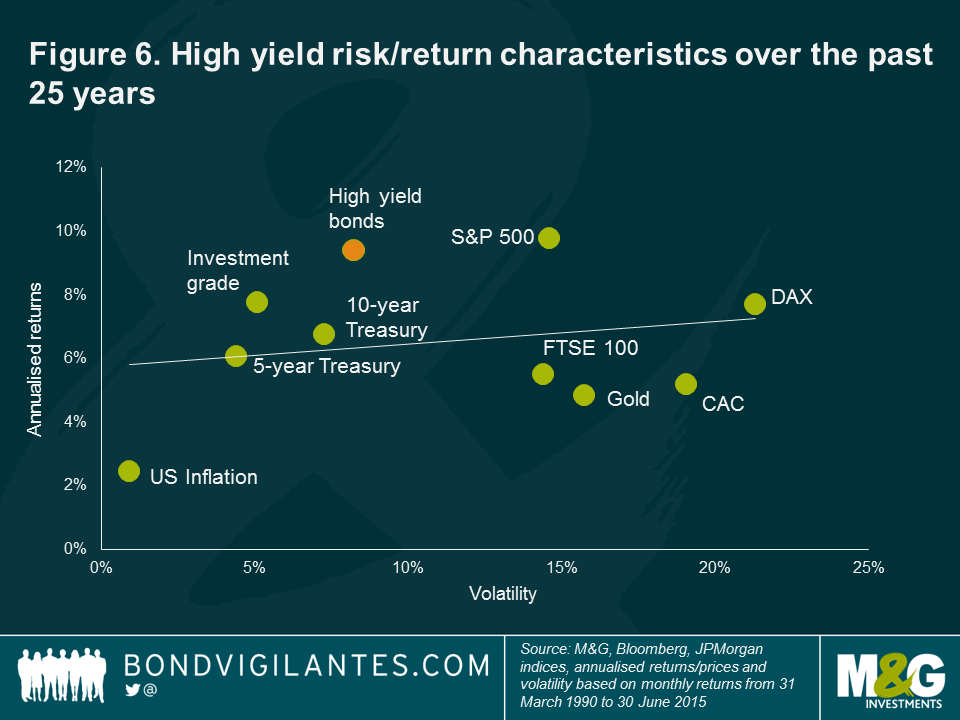

High yield (HY) has done particularly well since the aftermath of the 2007-08 financial crisis (except in 2015, given the plunge in oil prices). The asset class has benefited from the so-called Goldilocks scenario, in which growth is strong enough to fuel earnings, but not so much to force interest rates significantly higher. This has kept default rates low, at a time when the yield-tourists were happy to go down the capital structure in order to lock in good income.

This, however, started to turn this year as 2-year Treasuries yield 2.7%, with little risk, making Non-Investment Grade businesses less attractive on a risk-adjusted basis. Markets have been merciless: US HY spreads, for instance, have widened more than 100 bps in barely two months. Still, the asset class is one of the very few sectors in the black this year, largely supported by a sharp reduction in supply: as interest rates have gone up, companies have flocked to the leveraged loan market, a cheaper form of finance. The move has also been welcomed by investors, happy to receive a variable interest rate in a rate-rising environment – and also happy to seemingly ignore the deterioration in lending standards and the weak covenants attached to those loans.

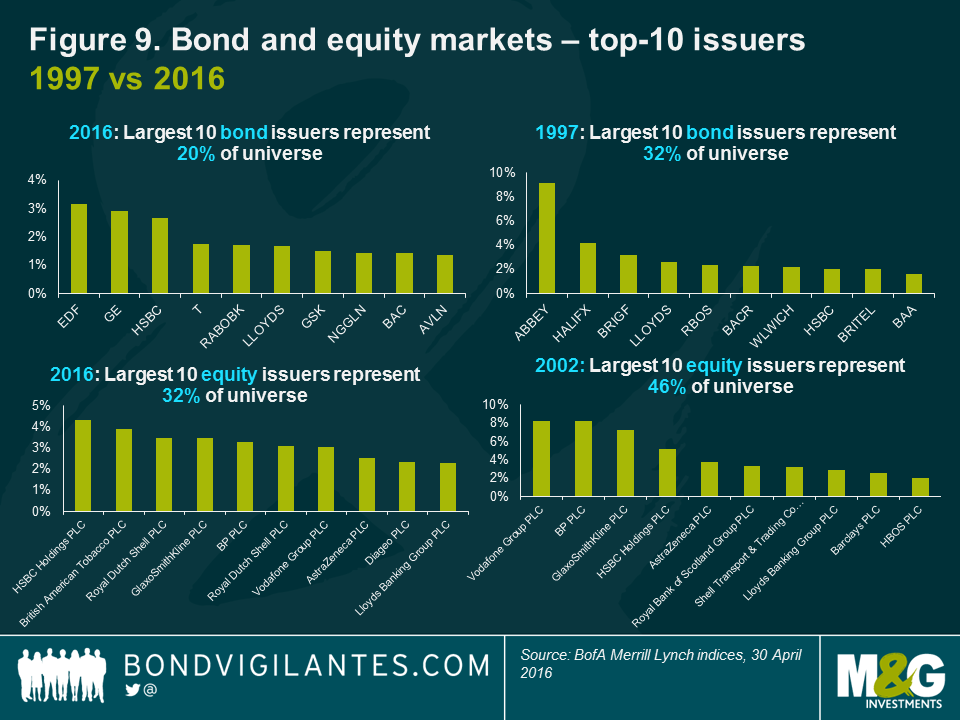

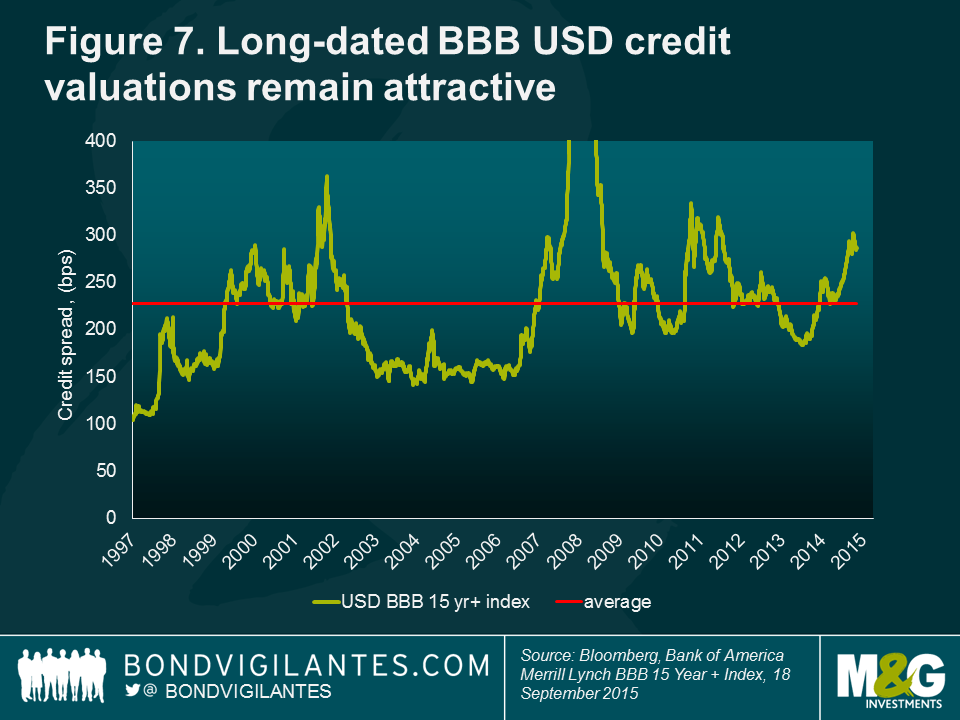

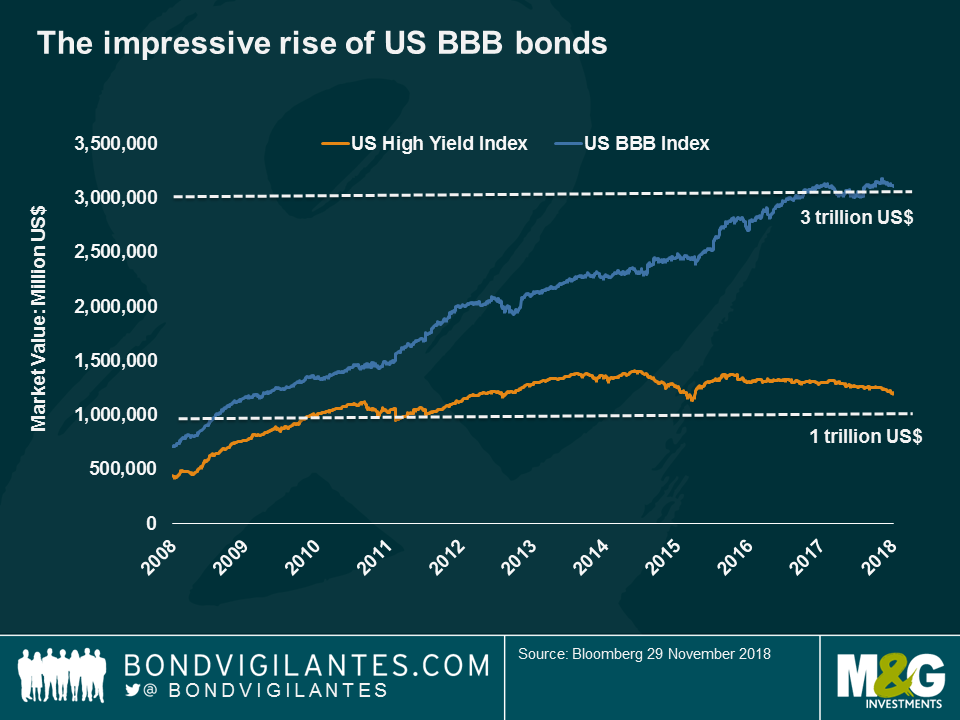

If short supply has helped HY, the opposite has dragged down US Investment Grade (IG) corporate bonds so far this year: a decade of cheap money has helped US IG companies issue billions of dollars worth of debt, often used to increase dividend payments or buy-back their own shares, enhancing equity prices. The market value of the IG rating bucket just above junk, or BBBs, has actually swollen to $3 trillion, more than twice its level a decade ago. It is now almost three times the size of the entire US HY market, raising concerns about the effect of potential downgrades in the HY universe.

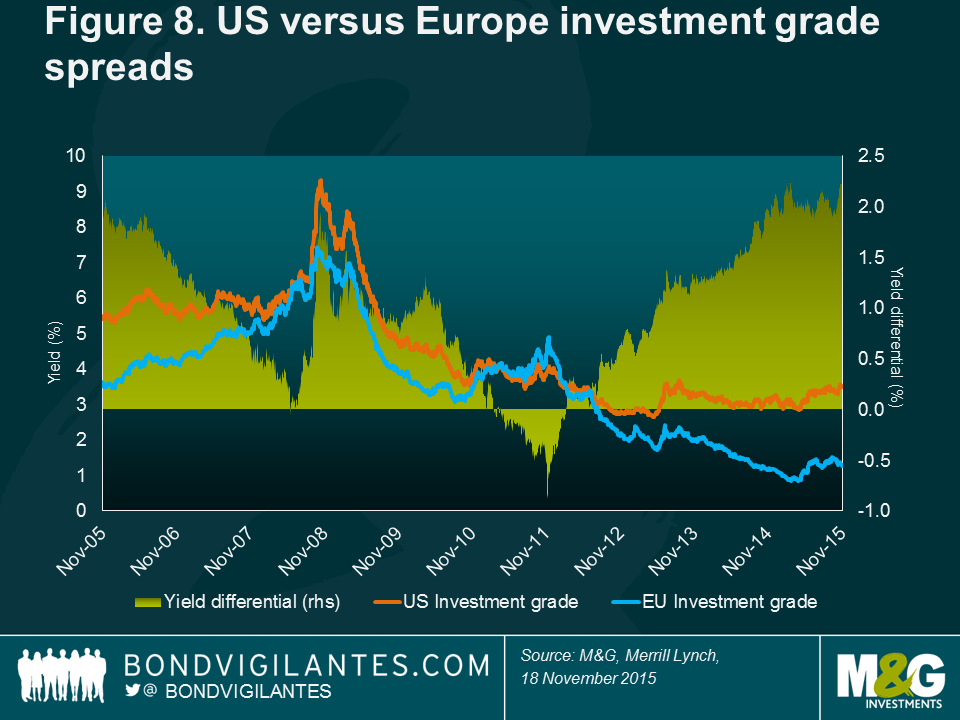

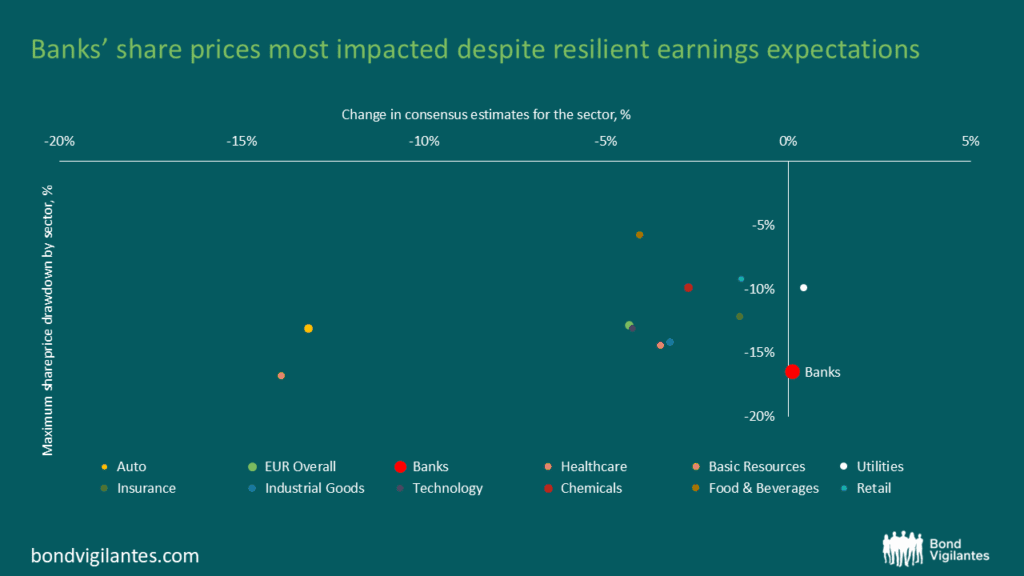

One credit area, though, that has traditionally benefited from rising rates is banking, as financial institutions borrow short-term money in order to make long-term loans, so rising rates can boost their profit margins. Banks have also better capitalised balance sheets, following more and tougher regulation after the Financial Crisis – once compared to casinos, some banks look and trade now more like utilities. Banks could also benefit from what it is still a positively-growing global economy. Valuations might be more attractive in Europe, as the ECB’s QE programme has only bought traditional non-financial bonds, leaving bank debt with relative high yields per a given credit quality.

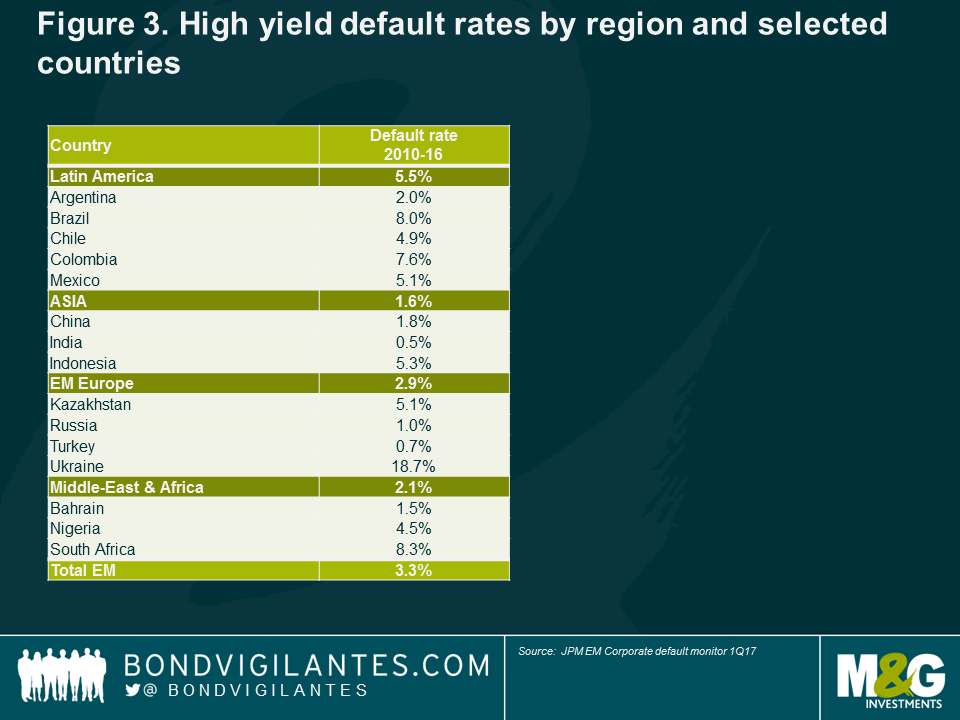

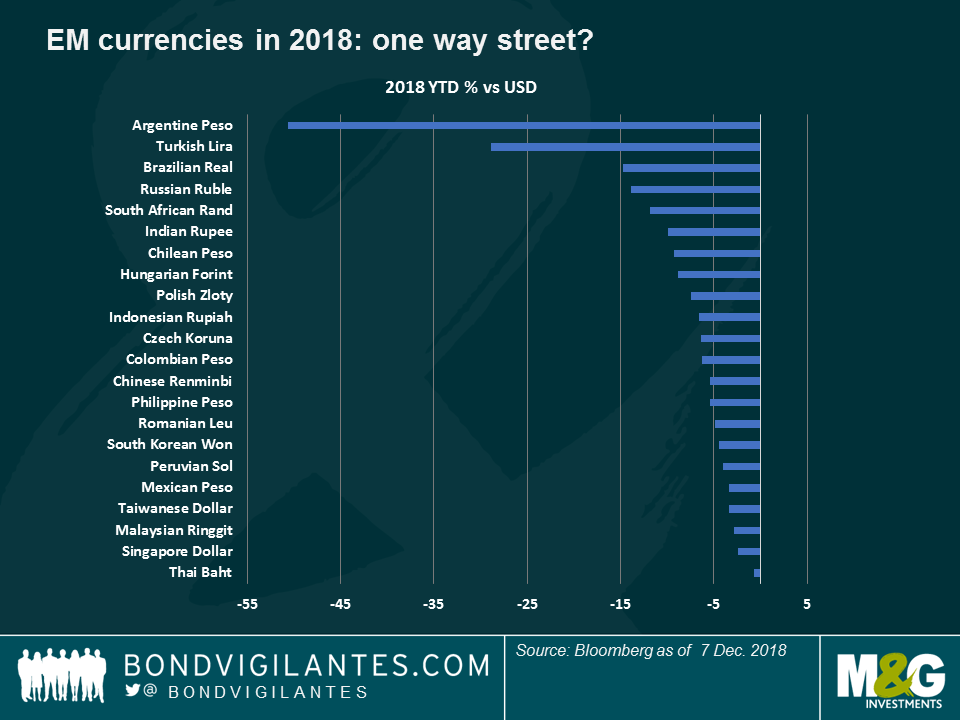

If we are looking for growth, Emerging Markets (EM) seem to be enjoying more of it than Developed Markets, and are forecast to continue doing so. EMs may also be more attractively valued going into 2019, following a poor 2018, when they have been hit by a rising dollar, the ongoing trade wars, a slowdown in China and idiosyncratic stories in Turkey and Argentina. Nobody knows what 2019 will bring, as some of the headwinds that shook the asset class in 2018 are still prevalent, including the trade tensions that could hinder global growth. However, and much to EM’s relief, dollar strength might be contained by an increasing US Budget deficit and a potential slowdown in US growth.

The one thing that seems certain is that volatility is here to stay – but that brings opportunity. We saw in 2018 how Brazil’s election substantially lifted the Real and reduced the country’s bond yields. Next year may bring us further opportunity, with scheduled general elections in India, Argentina, South Africa, Ukraine and Nigeria. Following this year’s sell-off, with some EM currencies down 20% or more, valuations are more attractive.

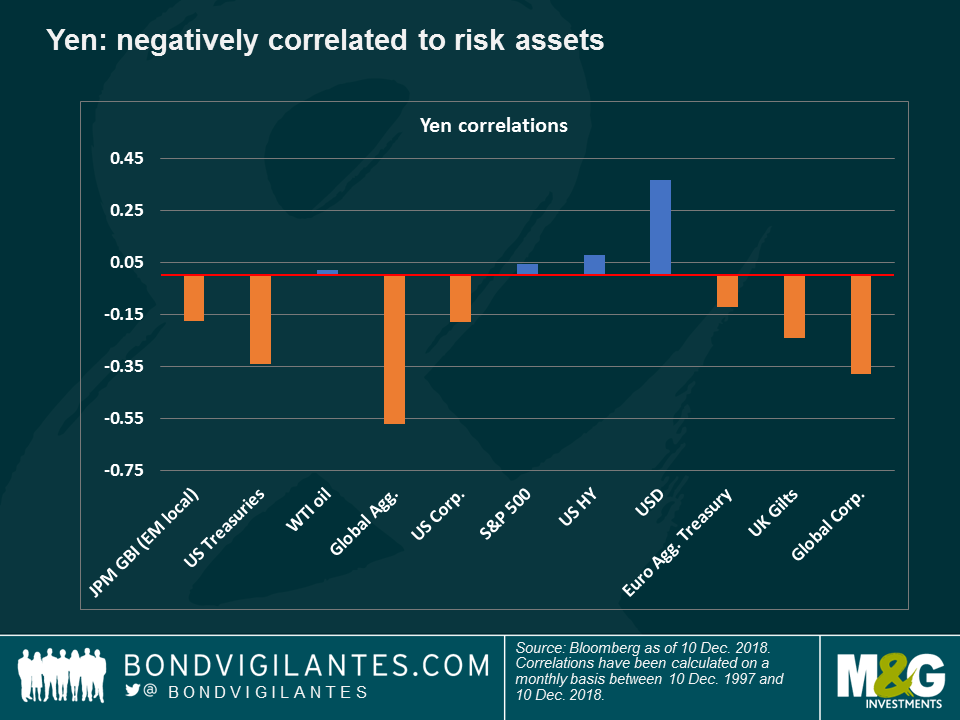

The one currency that has (just about) held its value against the dollar this year is the yen. Despite the country’s fragile economy and the central bank’s multi-billion yen stimulus, the currency has continued to offer certain protection to investors – either because of valuation, its safe-haven status, or because of the diversification that it offers to US and European investors. As seen in the chart, the currency has low correlation to not only risk assets, but also a negative correlation to the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index, the bellwether of fixed income markets. This year, for instance, the yen strengthened against the US dollar from mid-July to mid-August, during the peak of the Argentinean and Turkish turmoil that hit EMs and credit markets.

All in all, there are few presents from Santa this Christmas after some major repricing across asset classes, which could turn into opportunities for value-seeking, long-term investors in 2019. Until then, our best wishes to our readers for this Christmas and the New Year – may it bring you positive surprises, of the kind not tracked by any index.

1: Home ownership and wage growth – a new vision

Historically, the relationship between wage inflation and unemployment has been strong and is famously revealed in the Philips curve. However, this relationship has broken down over the past decade, causing much head-scratching among economists and central bankers: in the US, wages have failed to significantly rise despite a five-decade low unemployment rate and strong economic growth; in Britain, the present 4.1% unemployment rate is at the lowest since Brian Clough became Nottingham Forest manager in 1975 – yet, annualised consumer inflation has dropped this year from 3% to the present 2.4%. To cast some light on this puzzling question, former Bank of England MPC member and Dartmouth College professor Danny Blanchflower and colleague David Bell have come out with a different view.

According to the two academics, it is not unemployment what really has been driving wage growth since the GFC, but underemployment – or the willingness of current workers to increase their working time without getting more money.

Why are people willing to work more for free? Some attribute this to the decline of unionism and globalisation, but these trends have been going on for some time. A more probable and recent reason, the academics argue, is home ownership rates, which started declining in 2004 at a rate that only accelerated with the outbreak of the GFC in 2007. Renting a home, instead of owning it, seems to reduce workers’ bargaining power as they feel more unstable and hence, insecure. Tough news for workers as in the US, the home ownership rate has plunged to 63.9%, down from 69% in 2004; in Britain, it stands at 63.4%, down from an all-time high of 73.3% in 2007.

2: Tobacco: up in smoke

If markets are supposed to be mirrors of societies, the bond universe is certainly reflecting the world’s and the new generation’s increasing value for health. “Peak smoking” in the US was in the 1960s, when an adult smoked an average of over 11 cigarettes per day. That has fallen to 4 and continues to decline. Tobacco firms have been hit for years as falling consumption and tougher regulation hit sales and margins, but this year they are also facing new pressure from authorities keen to ban some of their most popular flavours. As bond investors embracing Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) criteria, we also have seen increased interest from clients in excluding tobacco bonds from portfolios. Could these hard exclusions of cigarette companies be about to become mainstream for bond investors?

Well, at last it has happened. Ten years after the global financial crisis began, we have reached a place where synchronised global economic growth is more than just a pipe dream and the prospect of central banks moving away from their extraordinary ultra-loose monetary policy stances of the last decade is finally a reality.

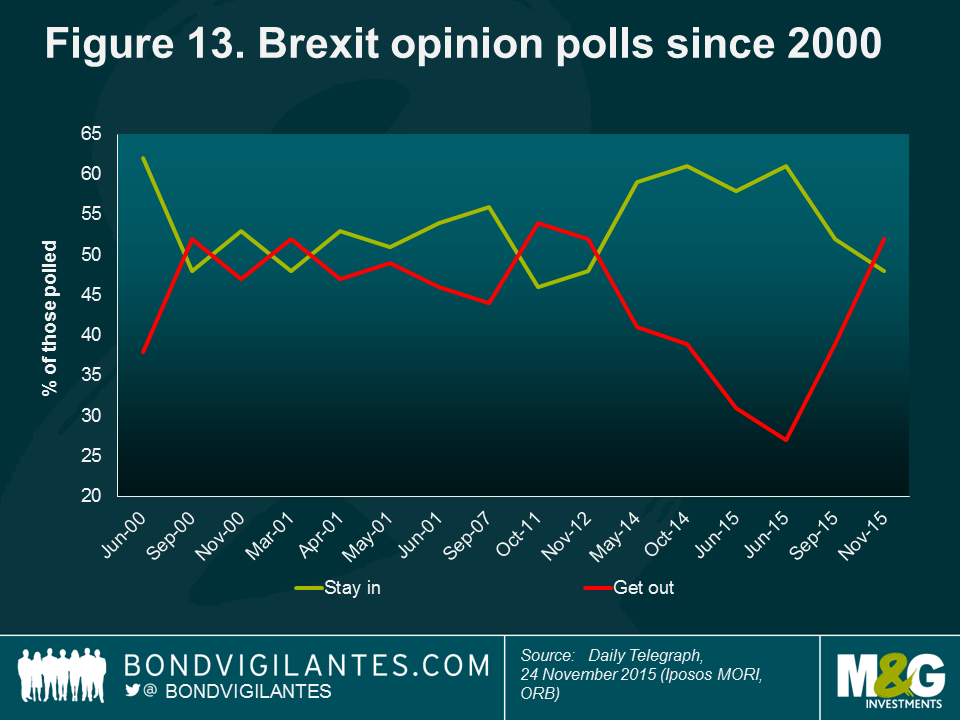

There has been much excitement in recent months about the robust and broad-based nature of global economic growth. However, this is not to gloss over the risks that remain. Chief among these is inflation (or the lack thereof). With the notable exception of the UK, where sterling post-Brexit referendum weakness has pushed the Consumer Prices Index as high as 3% in recent months (see box on Brexit), there have been more column inches devoted to softening than hardening inflation trends (see box on inflation).

A broadly rosy US outlook

Despite the solid performance of the US economy, inflation there has remained weak. Indeed, outgoing US Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen has described 2017’s low inflation as a mystery. Bond investors are split into two camps: does this weakness reflect temporary factors, or is there something more structural going on? If it is the latter, the Federal Reserve should be worried as there is little that monetary policy can do to combat deflationary forces like globalisation, demographics and technology improvements.

I think the arguments suggesting that the recent low inflation numbers reflect transitory factors and some positive supply-side developments look valid. For example: the increase in healthcare costs following the introduction of Obamacare has been lower than expected, while the introduction of unlimited data plans by cell phone providers has shown up in the official statistics as a sharp decline in prices. Looking ahead to 2018, a tight labour market should foster wage growth, while the potential for lower corporate tax levels could encourage higher domestic and international investment.

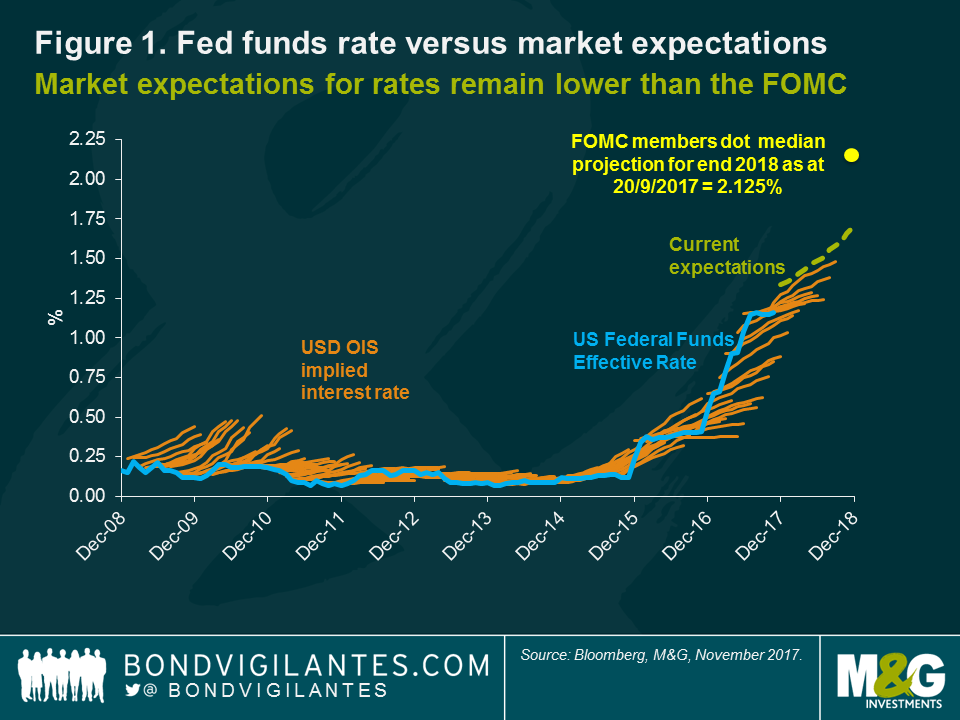

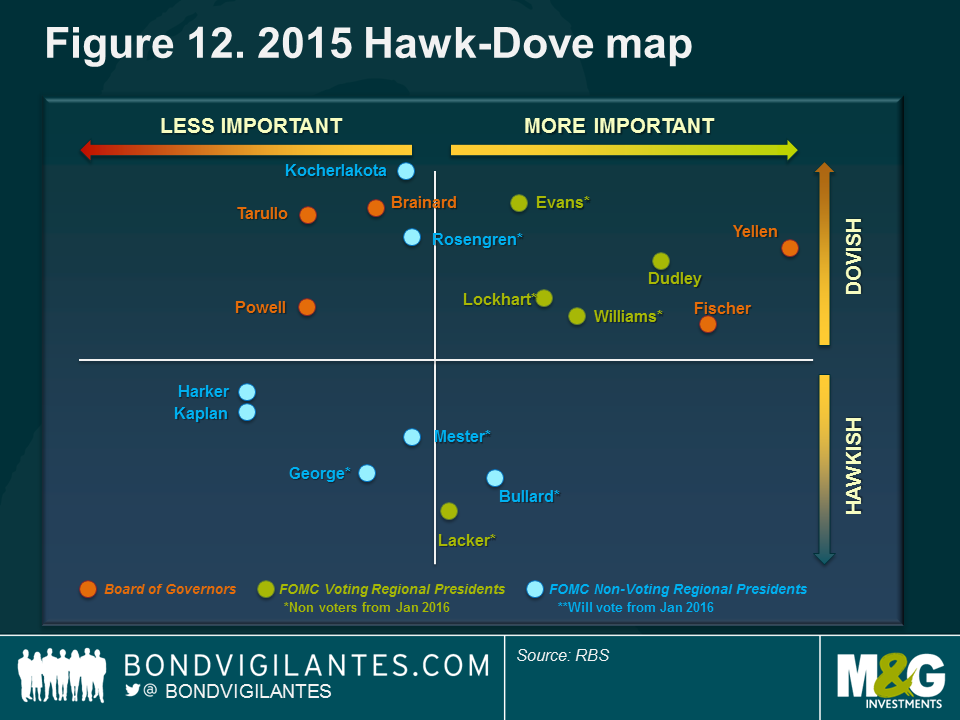

I expect the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) under new chairman Jerome Powell to continue to normalise rates gradually in 2018. Market pricing suggests a similar view, though expectations for the Fed Funds rate at the end of 2018 are around 50 basis points lower than the FOMC dot median projection would suggest (Figure 1).

The value of investments, and the income from them, will fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested.

All change at the Fed?

President Trump confirmed in November that Jerome Powell will replace Janet Yellen as Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve from February 2018. So what can we expect from the 16th chair of the Federal Reserve – the first non-economist to lead it since 1979? While Powell’s background differs from the norm, his policy stance is not expected to. The muted bond market reaction on the day of the announcement underlines his status as the status-quo pick. Had alternative candidates John Taylor or Kevin Warsh been appointed, the bond market may have sold off in anticipation of a more aggressive Fed hiking cycle and a faster QE taper than Yellen and the current Board – of which Powell forms part of – have implied. Indeed, 2017 marked Powell’s fifth year on the Board of Governors and in that time he has proven to be supportive of gradual interest rate hikes, voting consistently as part of the Yellen-led consensus.

Given Powell’s corporate background, however, it’s not a stretch to surmise that he may be more partial to lighter-touch financial regulation (something that Trump has long been an advocate of) than some of his predecessors. For example, with respect to the Volcker Rule (governing banks’ ability to speculate with retail deposits), Powell stated in a speech in October that “there’s a lot of room to address the burden” and that in terms of regulation “we can do it more efficiently”. This may have been noted by the market: since the announcement of Powell’s appointment, US swap spreads in the long end, though still negative, have moved back towards positive territory, suggesting that the market may have started to price in the prospect of an easier regulatory environment.

Positive surprises from Europe

Europe’s broad economic growth was the surprise of 2017. Many business activity indicators are near record highs, consumer confidence is very strong, and the third quarter’s growth rate (2.5% yoy) was the strongest for 10 years. Challenges remain, such as the level of bad debts in the Italian and Spanish banking systems, but even these are starting to show signs of improvement.

The European Central Bank (ECB) under Mario Draghi can rightly claim a significant contribution to this turnaround. Its extremely easy monetary policy stance has allowed the financial system to heal and has given businesses and consumers confidence to invest and spend. Importantly, the ECB has given guidance that it will retain a very easy monetary policy stance, announcing an extension of quantitative easing (QE) until September 2018, at a reduced level of €30 billion a month. As in the US, 2017 inflation levels have been stubbornly low, and there is currently little evidence of a return towards its target of close to, but below, 2.0%.

In November, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) reversed its emergency rate cut undertaken in the wake of the Brexit referendum with what can be described as a “weak hike”. This may prove to be a one-off adjustment. The rate rise is difficult to justify given the continued political uncertainty that surrounds Brexit and the slow progress of UK-European Union (EU) negotiations. We expect to see more signs of slowing investment, falling consumer confidence and economic weakness unless a material agreement or transitional deal can be reached on the future UK-EU trading relationship – discussions on which can finally get underway after the two sides struck a last-minute deal on the first ‘divorce’ phase of negotiations in early December. The MPC, however, clearly has a different view and is worried that there is limited spare capacity in the economy that may lead to higher wages and above-target inflation. The good news is that this single rate rise of 25 basis points will have a limited effect on the real economy. Monetary policy remains highly accommodative, real interest rates are negative, and the Bank’s balance sheet is still large.

The world’s fourth-largest economy, Japan, is currently experiencing its second-longest economic expansion since World War II, having grown for seven successive quarters. As in Europe, the Bank of Japan is pursuing ultra-easy monetary policy and has committed to overshooting its 2% inflation target. As a result, it is unlikely that the Bank will alter its current stance of setting the short-term interest rate at -0.1% and 10-year Japanese government bonds at around 0%.

In China, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) will look to mitigate systemic risks, suggesting a monetary policy tightening bias in 2018. The emphasis at 2017’s Party Congress (an event that occurs once in five years) on the quality of economic growth means continued policy efforts on leverage controls and tightening in the housing sector, which could weigh on public and housing investment. That said, growth looks to be becoming more self-sustaining, with robust consumption and external demand. I expect that China will continue to contribute meaningfully to both global as well as emerging market economic growth in 2018.

How high can rates go?

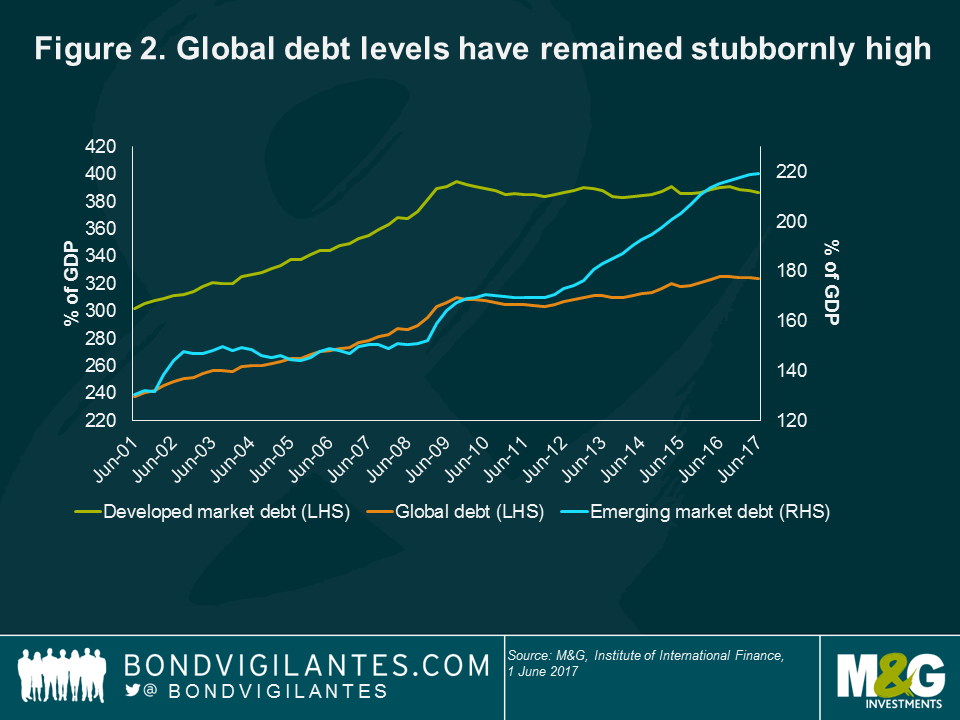

Many economists have attributed the slow pace of growth that we have seen during the economic recovery to a global deleveraging cycle aimed at reducing debt levels from what appeared to be unsustainable levels. So 10 years after the global financial crisis (as well as a European debt crisis and an oil crisis), where are we within this global deleveraging cycle?

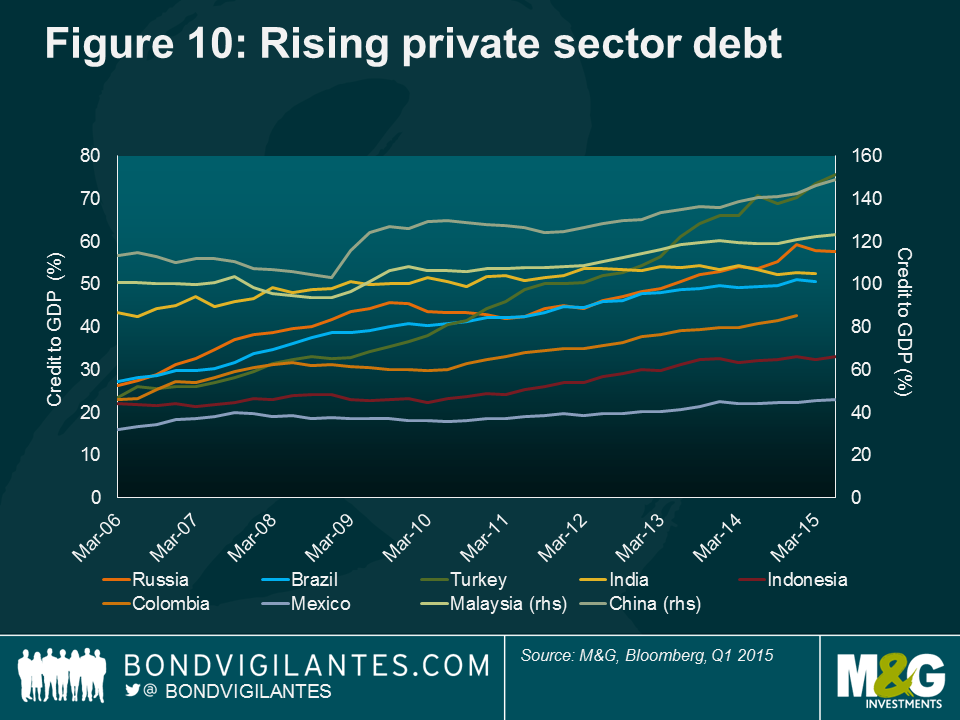

Figure 2 shows global debt levels in recent years across the largest developed and emerging economies. After peaking in 2009, total debt levels declined slightly before rising once again to a level of 324% of world gross domestic product (GDP) today. It also shows that while we have been experiencing a mild deleveraging cycle in the developed world over the past 10 years (primarily due to deleveraging in the banking sector), most of the recent increase in global debt levels has come from emerging countries (Chinese state-owned enterprises being an important contributor, for example). This unabated increase in global debt levels means that – all else being equal – peak interest rates for this economic cycle in most developed countries are likely to be lower than they have been in the past.

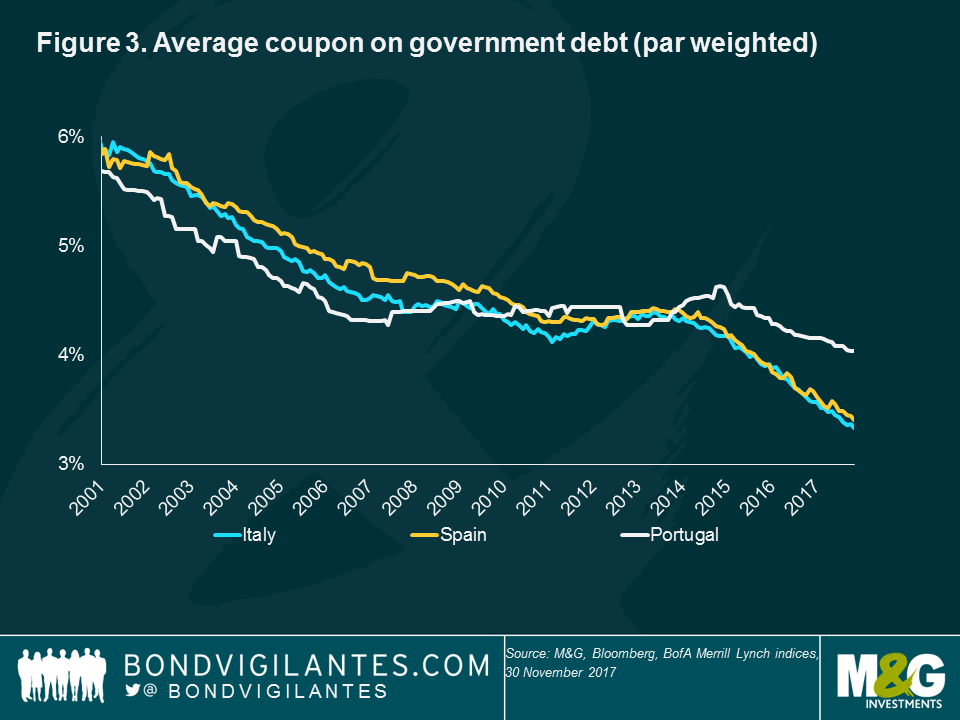

Another key metric in the sustainability of global debt levels is the average interest rate paid on that debt. In this regard, the ultra-loose monetary policies that we have seen in most of the developed world have provided a bit of respite for many governments’ debt levels. Figure 3 shows that five years of nil or negative ECB deposit rates have significantly helped Europe’s ‘peripheral’ countries reduce the cost of servicing their public debt. Spain, for example, has been able to reduce the average coupon that it pays on its debt from about 4.5% three years ago to around 3.4% today.

Assuming that the ECB’s QE programme will keep government bond yields low, we expect the cost of Spain’s debt to decline further during 2018. Its government has also taken advantage of low rates to increase the average maturity of its debt from 7.5 years in 2012 to around 9 years today – helping insulate it from future rate hikes or yield spikes.

Equally, the type of debt, such as fixed or floating rate coupons, must also be taken into account. The US household sector is arguably far less sensitive to higher interest rates than in the UK, as most mortgages in the US are priced off long-term fixed rates.

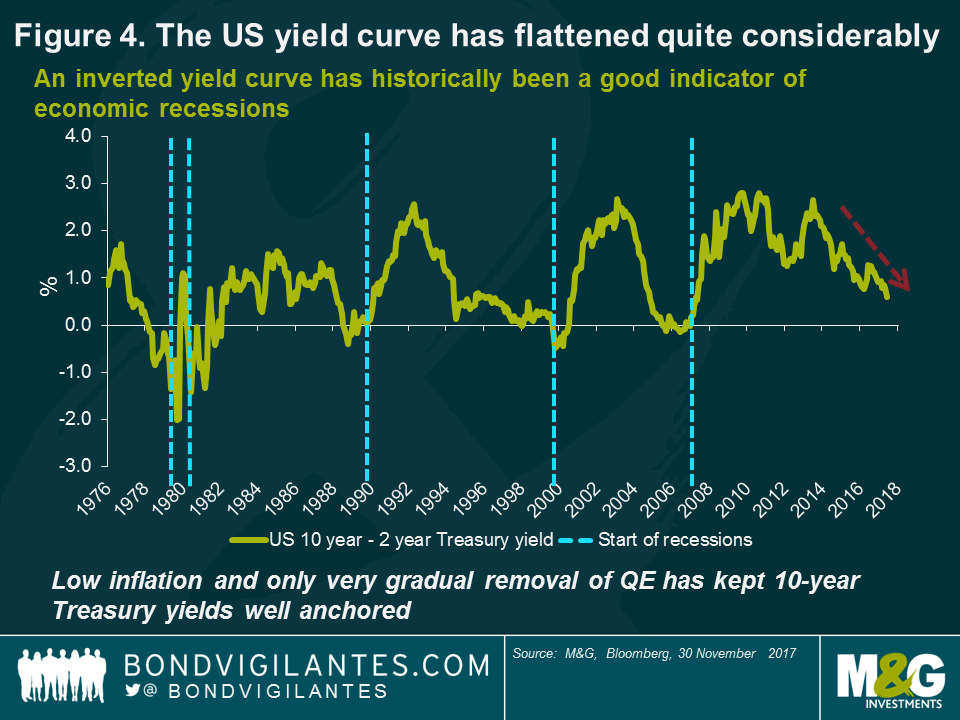

The fact that the Fed will need to keep raising rates to tighten monetary policy further is reflected in the adjustment that we have seen in 2017 in 2-year Treasury yields, which increased from 1.1% to around 1.8%. What is more surprising is that longer-term government yields have been extremely resilient: 10-year Treasury yields will end 2017 at around the same levels as they started. This combination of rising short-term yields and stable long-term yields has caused the US Treasury curve to flatten quite considerably in 2017 (Figure 4).

Historically, a flattening yield curve suggests an economic downturn (the yield curve inverted before each of the last seven US recessions). Given that the Fed could hike at least a couple more times in 2018, the curve could indeed become inverted if longer-term yields remain so well anchored.

So does the current shape of the yield curve signal an imminent recession in the US? Not necessarily. The persistent high demand for long-dated government bonds has been due at least in part to other important structural factors, such as slower productivity growth, lower inflation levels and an ageing world population. From a more technical perspective, the very gradual unwinding of the Fed’s balance sheet, the recent announcement from the US Treasury that it will sell more short-dated government bonds, and the purchase of longer-dated instruments by US corporations to pre-fund their pension liabilities in anticipation of tax reforms have probably also accelerated the recent yield curve flattening movement.

Given that these technical influences may lessen, and that the closing of the global output gap could also lead to higher inflation, we believe there could be downward pressures on long-dated US (or even UK or European) government bond prices in the months ahead. For these reasons, we continue to find many long-dated government bonds rather expensive at current levels.

The year of the great QE taper

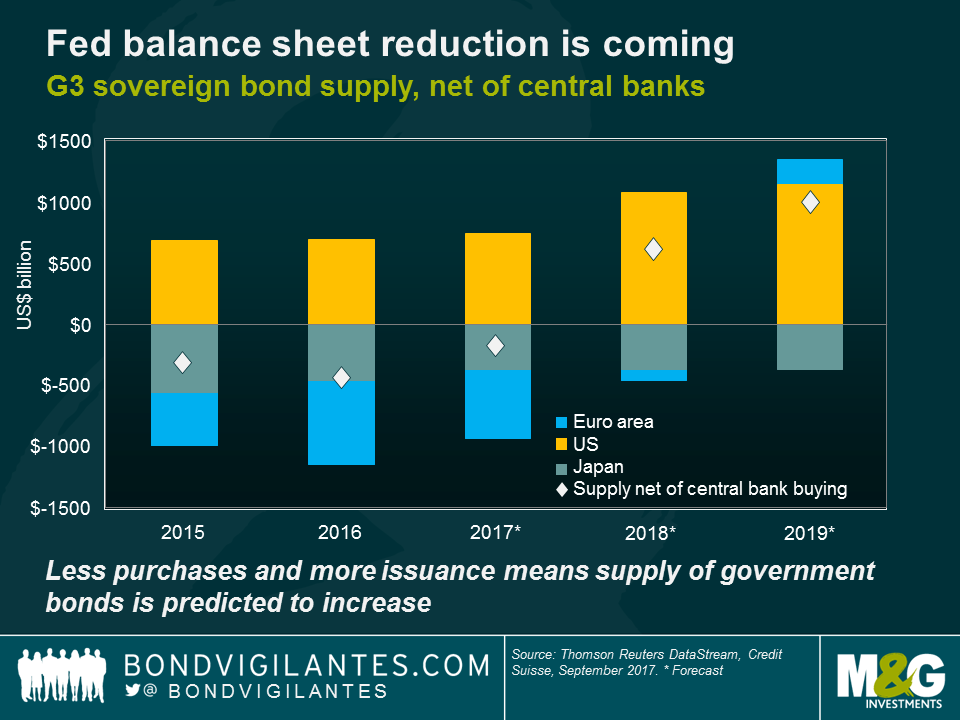

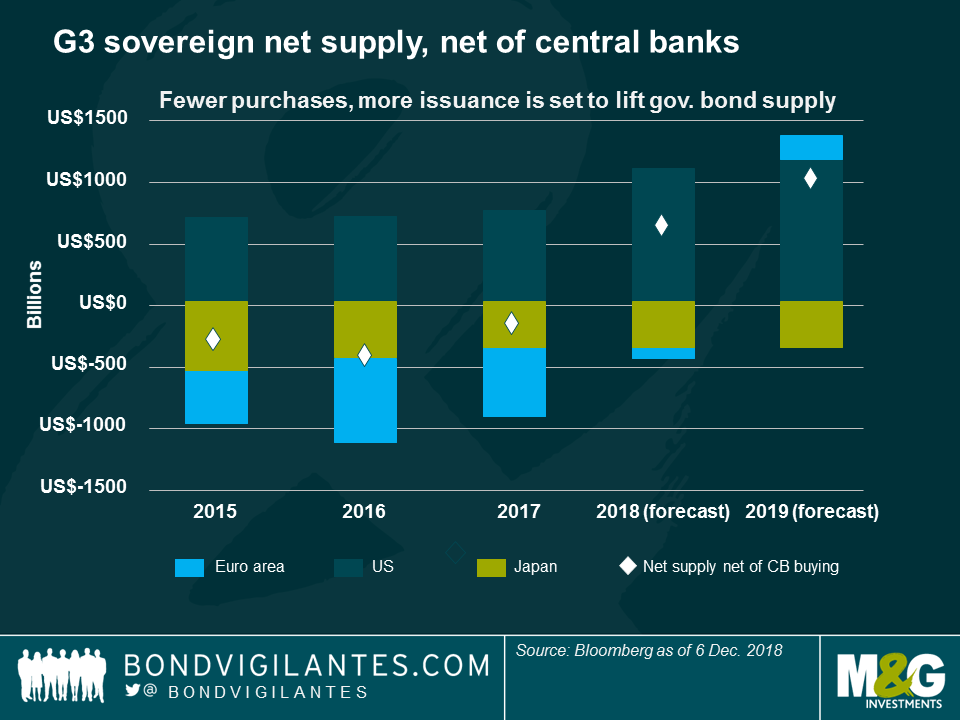

It may be a continuation of the status-quo with a Powell-led Fed, but that doesn’t mean it’s more of the same. Balance sheet reduction and the great QE taper are set to take centre stage in 2018.Almost 10 years to the day of the onset of the global financial crisis, the Fed announced its process of balance sheet normalisation, committing to gradually reduce its balance sheet by US$10 billion per month (split 60/40 between US Treasuries and mortgages). From January 2018, the monthly reduction doubles to US$20 billion. The Fed-imposed limits will continue to increase every three months, until the total monthly reductions reach US$50 billion in Q4 2018.The technicals are changing. After years of central bank demand for Treasuries, 2018 is the first year in a long while when technical support for US Treasuries may waver, as net supply effects kick in (see chart).

After years of shrinkage in net G3 government bond supply (net of central bank QE purchases), QE tapering by both the Fed and the ECB means that 2018 will likely see more sellers than buyers of G3 government bonds. The implications are clear: the days of record low government bond yields may well be behind us. If QE reduced government bond yields on the way in, the opposite may well prove true on the way out.

Beware credit quality

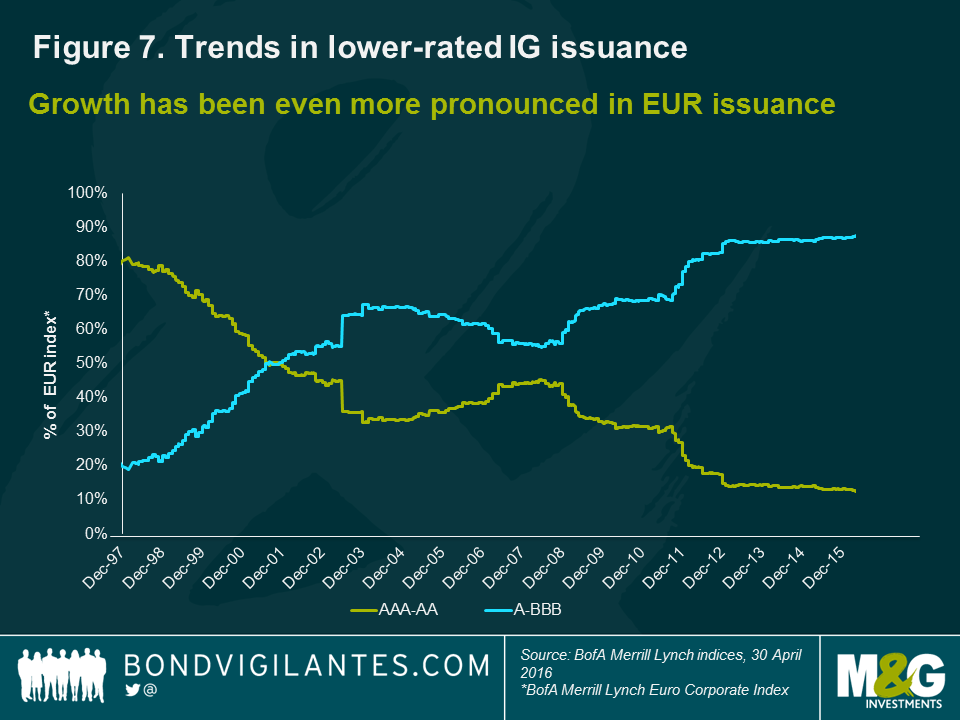

The quality of investment grade credit has seen significant deterioration in recent years. This has partly been voluntary, with companies believing that adding leverage to their balance sheets can enhance equity returns, but it also reflects the wider-scale credit downgrades that banks and financial institutions in particular experienced during and after the credit crisis. In 2000, for example, the US credit market contained a little over 30% in BBB rated securities (and the nascent eurozone credit market just under 10%). This has risen significantly since the start of the millennium, to the extent that global credit markets are now almost 45% exposed to BBB rated issuers, and this is trending higher. As a result, today’s global credit market has a far riskier credit profile than a decade earlier.

This is particularly important in the context of today’s credit spread levels. If you were to look at the overall global investment grade universe spread level in isolation, you could be tempted to think that despite the rally in corporate bond prices in recent years, valuations are simply back to their long-term average. However, when you take the aforementioned deterioration in credit quality into account, the picture is less rosy. It suggests that global credit is now into expensive territory rather than fair value. Of course, some of the reasons that have caused this are valid: ECB bond-buying, still-low default rates and continued demand for income-producing assets.

In high yield, it remains an issuer’s market, with bondholders’ rights suffering further degradation over the course of the year. According to Moody’s, so-called HY-lite (bonds that lack fundamental investor protection) levels have been rising steadily in Europe since 2013, from a level of well below 10% to around one third of all bonds coming to market today.

There are few immediate warning signs, as companies still benefit from a favourable macroeconomic environment, in a world of synchronised global growth and benign financial conditions. Companies can continue to benefit from cheap refinancing conditions for the foreseeable future.

Nevertheless, to my mind, deteriorating credit quality, and lower rewards for taking risk have made credit (both investment grade and high yield) a far less attractive asset class in 2017 than in previous years. For these reasons, I have reduced my overall exposure to corporate bonds this year, although as ever, I will monitor the market closely going into 2018 for better buying levels.

Emerging markets: resilience and relative value

After a nervous start to 2017, President Trump-related concerns for emerging market (EM) investors have broadly eased – the difficulties of getting things done domestically has constrained the president’s ability to do as much internationally as he may have initially hinted at. And in the event, sentiment towards the emerging bond markets has held up well in 2017. Optimism over improving (and synchronised) global economic growth has played a part here, as have firmer trends in commodity prices and China’s better-than-expected performance.

In addition, some topical risks started being ‘priced out’ of the emerging bond markets as the year progressed, including developed market political risks and worst-case scenarios in US/China relations (the US has not named China as a currency manipulator or embarked on a trade war).

Emerging market fundamentals and valuations still look selectively attractive versus developed markets. Growth rates in many emerging economies exceed those in the developed world, for instance, while many also boast far lower debt-to-GDP ratios. Yields on both local and hard currency emerging market sovereign debt comfortably outstrip those on developed market government bonds.

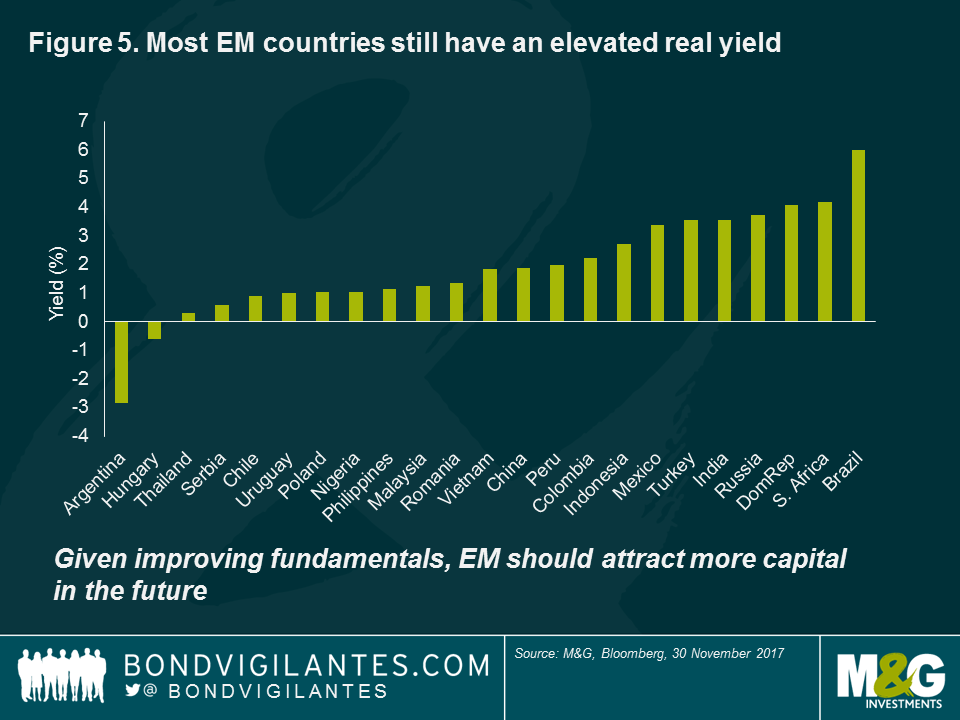

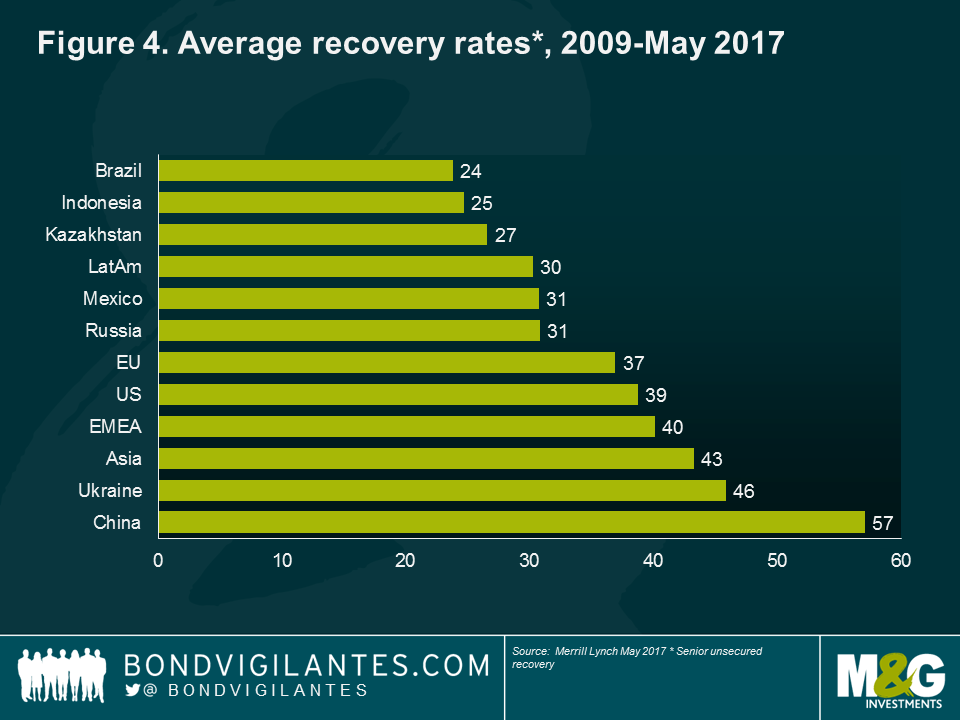

As Figure 5 shows, high real yields underline the appeal in regions such as Latin America, where inflation is expected to fall in several larger markets, including Brazil and Mexico. However, I do remain concerned about the scale of China’s debt and, although a ‘hard landing’ is unlikely, we believe that tight spreads in the country’s bond market do not properly compensate for the risks.

More generally, the implications of higher US interest rates still need close attention. However, for many EM economies, the higher US rate environment is less challenging than in previous cycles, due to improvements in their current accounts, and lower overall levels of US dollar-denominated debt. That said, US rate increases could pose a headwind for certain emerging economies, particularly those more dependent on US dollar funding.

Absent the Fed falling behind the curve, my view is that EM debt markets can withstand slow and gradual US monetary tightening. Their high real yields should provide something of a cushion against further US hikes. A strengthening global economic outlook, meanwhile, also has favourable implications for the credit quality of EM bond issuers, as EM credit ratings actions typically correlate with growth rates.

Inflation: still missing in action

The lack of inflation in the global economy (with the current exception of the UK for Brexit-specific reasons) despite near-record levels of employment in much of the developed world remains one of the great puzzles of the post-financial crisis world. Conventional economic theory suggests that a shortage of labour will drive up wages as companies compete for the dwindling supply of workers, in turn fuelling higher inflation. But there is little sign of this happening just yet.

Of course this is not a new phenomenon, with global inflation having been on a downward trajectory for the past couple of decades. Many theories have been put forward to explain this trend. An increasingly open global economy has undoubtedly had a major impact, with the availability of cheaper goods and services from China and other emerging markets helping to keep consumer prices lower. Another key theme centres around advances in technology and artificial intelligence. As well as driving down the costs of production, increased automation may also reduce the demand for human labour, potentially keeping wages lower.

The rise of the so-called gig economy – the part of the labour market consisting of short-term or temporary jobs – is another important trend which has been attracting a lot of attention in recent years. With uncertain working hours and limited rights compared to permanent employees, gig economy workers will typically have very little bargaining power when it comes to setting wages. The prospect of a 1970s style wage-price spiral – where heavily unionised workforces secure ever higher wage settlements – looks remote in this context.

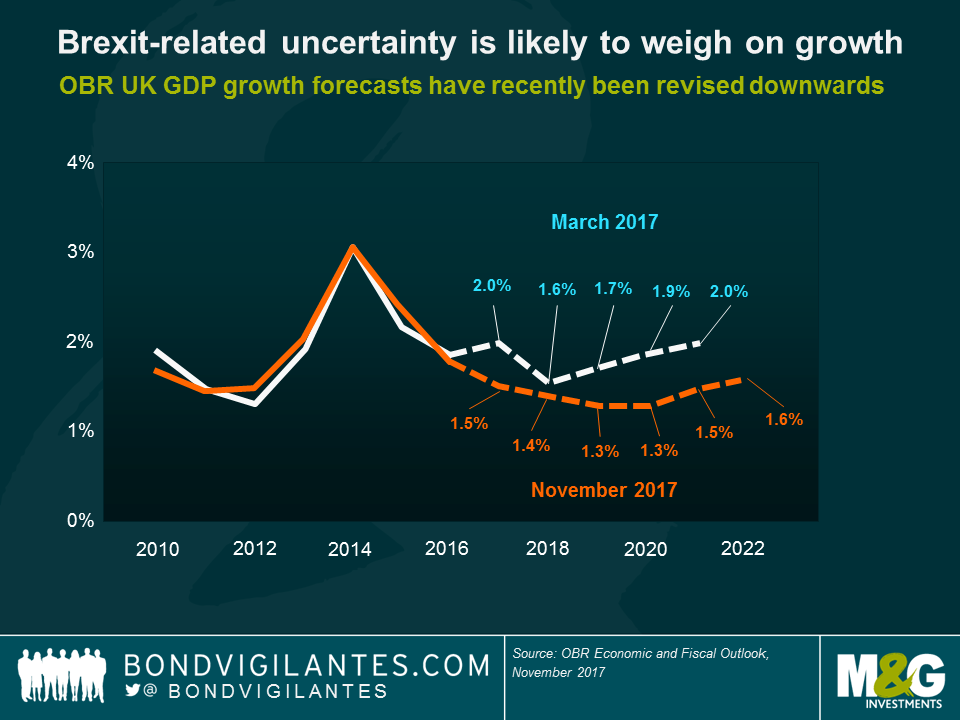

Brexit: Economic as well as political uncertainty

While the politics surrounding Brexit has never been far from the headlines in 2017, something that has perhaps fallen under the radar is the economics. After the referendum, the UK economy initially surprised both economists and the market, with growth and consumer data staying robust into the end of 2016.However, the most recent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts make for dire reading. Where previously the OBR was expecting growth to hit a low in 2018 and pick up gradually thereafter, the figures published in November 2017 now project growth downgrades to all five years of the forecast period, with growth bottoming out two years later in 2020. Either way, gone are the days of 2% annual growth rates.

The growth downgrades come largely from the OBR’s revision to its productivity forecasts. After years of overestimating growth, assuming productivity would return to pre-global financial crisis annual trend growth rates of around 2%, this assumption has now been halved, with productivity growth now expected to average closer to 1% (adding a cumulative £91 billion to the forecast for public net sector net borrowing over the next five years).This adjustment makes no assumption of the ultimate UK Brexit deal, however, and with changing demographics and a shrinking working population, it’s entirely possible that these productivity downgrades may still prove too optimistic. Should the economy disappoint – or Brexit start to bite – the UK may have no choice but to relax its fiscal austerity stance, bringing the focus back to the UK’s credit rating (currently AA), debt burden and currency once again.

More than one-third of the way through the Brexit negotiation period, the two sides have finally limped to an agreement on the first phase of negotiations – the ‘divorce’ settlement. Now all eyes will turn to the status of the future trading relationship. Despite the still-uncertain outlook, one thing is becoming clearer: the fundamental outlook for the UK economy is not looking pretty.

This information is not an offer or solicitation of an offer for the purchase of shares in any of M&G’s funds. Distribution of this document in or from Switzerland is not permissible with the exception of the distribution to Qualified Investors according to the Swiss Collective Investment Schemes Act, the Swiss Collective Investment Schemes Ordinance and the respective Circular issued by the Swiss supervisory authority (“Qualified Investors”). Supplied for the use by the initial recipient (provided it is a Qualified Investor) only. In Hong Kong, this financial promotion is issued by M&G Investments (Hong Kong) Limited, Office: 16/F, Man Yee Building, 68 Des Voeux Road, Central Hong Kong; in Switzerland, by M&G International Investments Switzerland AG, Talstrasse 66, 8001 Zurich, authorised and regulated by the Swiss Federal Financial Market Supervisory Authority; in the UK, by M&G Securities Limited (registered in England, No. 90776) and, elsewhere, by M&G International Investments Ltd (registered in England, No. 4134655). Both M&G Securities Limited and M&G International Investments Ltd are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the UK and have their registered offices at Laurence Pountney Hill, London EC4R 0HH. M&G International Investments Ltd also has a branch located in France, 6 rue Lamennais, Paris 75008, registered on the Trade Register of Paris, No. 499 832 400 and a branch in Spain, with corporate domicile at Calle Fortuny, 6 – 4º A, 28010, Madrid registered with the Commercial Registry of Madrid under Volume 32.573, sheet 30, page M-586297, inscription 1, CIF W8264591B and registered with the CNMV under the number 79. For Hong Kong only: If you have any questions about this financial promotion please contact M&G Investments (Hong Kong) Limited. The Portuguese Securities Market Commission (Comissão do Mercado de Valores Mobiliários, the “CMVM”) has received a passporting notification under Directive 2009/65/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and the Commission Regulation (EU) 584/2010 enabling the fund to be distributed to the public in Portugal. M&G International Limited is duly passported into Portugal to provide certain investment services in such jurisdiction on a cross-border basis and is registered for such purposes with the CMVM and is therefore authorised to conduct the marketing (comercialização) of funds in Portugal. For Singapore: for Investment Professionals and Institutional Investors only.

Whether you call it ‘Green’, ‘Responsible Investing’ or ‘ESG’ (environmental, social and governance), there is no doubt that it is now a firmly established part of the investment landscape, having evolved from something of a niche interest to a mainstream concern in the space of just a few years. Growing awareness of a range of environmental and social issues has seen an ever larger number of investors move their focus away from purely financial goals towards an approach that also considers the social and environmental impact of their investments.

A generational shift is under way

Over the coming years, we think the interest in responsible investing only looks set to grow, with millennial investors, in particular, likely to be a key long-term driver. While responsible investing has proved increasingly popular with investors of all ages, it is the millennial generation (broadly defined as those born between 1982 and 2000) which has shown the strongest enthusiasm for this form of investment.

According to research carried out by M&G and The Wisdom Council1, 9 out of 10 ‘millennials’ said they were interested in socially responsible investing and wanted to know more. Millennials were also twice as likely (64%) than investors over 55 (29%) to invest in a fund if social responsibility was part of the thesis.

While the overall earnings power of millennials is still in its early stages, the wealth and influence of this generation is expected to grow significantly over time. Millennials are set to become the largest demographic in the US over the next few years and, over the coming decades, are expected to inherit trillions of dollars’ worth of assets from the wealthy ‘Baby Boomer’ generation. In this context, we think millennials will become an increasingly powerful driver of the demand for responsible investments.

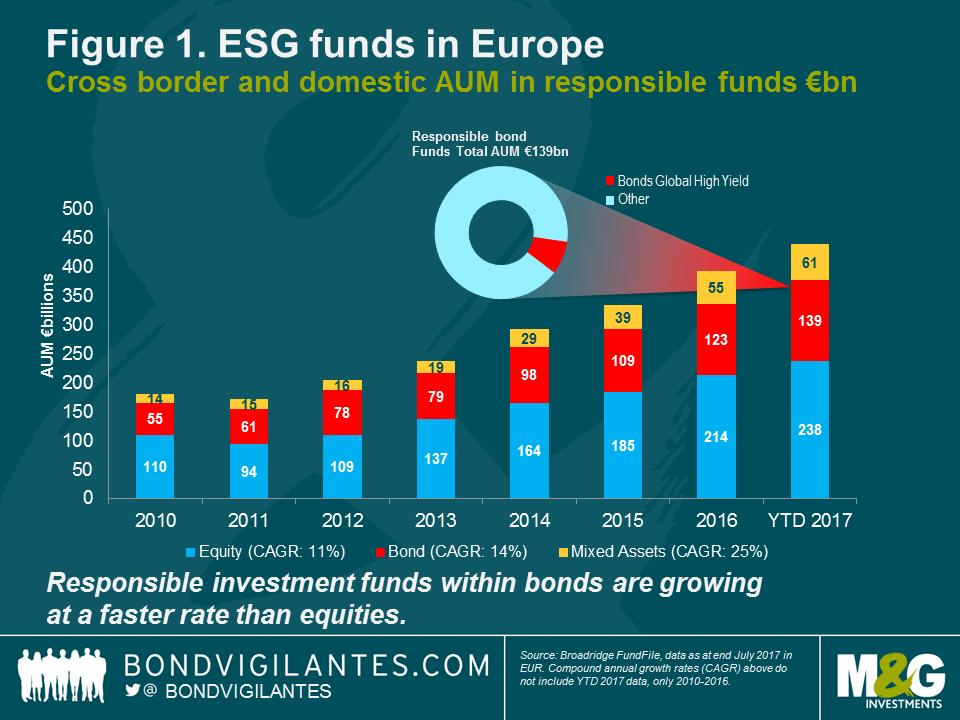

Indeed, this shift in perceptions and priorities is already manifesting itself in assets, especially in Europe, where ESG assets under management (AUM) have increased from €180 billion in 2010 to €438 billion as at 31 July 2017 (see Figure 1).

A notable development has been the growing number of ESG bond funds available to investors. While ESG equity funds still represent the majority of AUM, bond funds are quickly catching up, having grown at a faster rate than ESG equity strategies since 2010, measured using a compound annual growth rate.

Consequently, responsible investing will be a major growth area for both bond investors and the fund management industry alike.

There are, however, three key questions that need to be answered:

- What does ‘responsible investing’ actually mean?

- What outcomes are being targeted and how do we define and measure these?

- How can this framework, once established, be integrated into existing investment processes and portfolios?

In this paper, we take a cross section of ‘responsible investing’ approaches and consider how they may or may not work within the context of a global high yield bond portfolio.

- Research conducted by the Wisdom Council (www.thewisdomcouncil.com) with collaborative partners including M&G Investments, Aberdeen Standard Investments, Equiniti, Nutmeg and Royal London Asset Management.

ESG approaches from a high yield perspective

Fixed income assets make up a considerable proportion of most investor portfolios. However, while bond funds now represent a sizeable portion of the ESG universe, these are predominantly focused on investment grade issuers, with high yield bond funds accounting for only a fraction of assets under management.

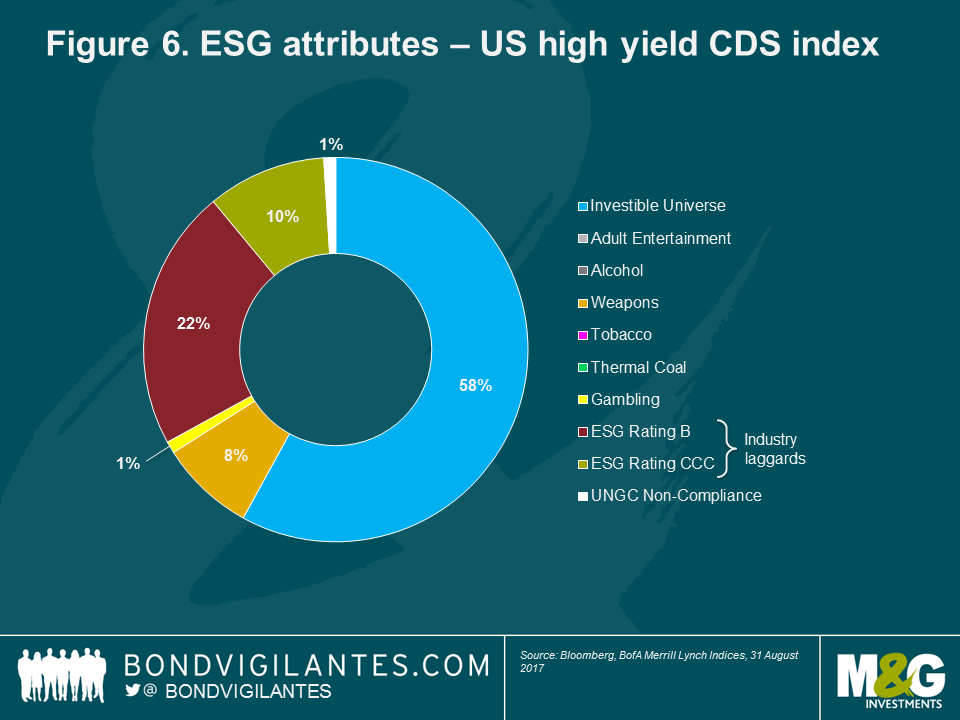

One potential reason for this is that the high yield market does not easily fit in with ‘off-the-shelf’ ESG methodologies. Table 1 outlines some of the most common ESG approaches and considers their suitability from a high yield perspective:

Table 1. Some common ESG approaches

| Description | Pros | Cons | |

| ‘Norms’-based screening | Excludes companies that are assessed to be in breach of widely accepted principals, such as the United Nations Global Compact principles on human rights, labour, environment and anti-corruption. | Broad acceptance by the investment community. Compliance has limited impact on the investible high yield universe. | Punishes purely by exclusion – limited scope for positive engagement. No flexibility to deviate from principles laid down – a ‘one-size-fits-all’ framework. |

| Negative screening (sector exclusion) | Excludes companies whose revenues are derived from specified sectors, such as tobacco, gambling or weapons. | Simple to apply and align with client preferences. | Fails to consider companies outside specified sectors that display poor ESG credentials. Subjectivity in terms of deciding which sectors should be excluded – eg, is nuclear energy good or bad? |

| Negative screening (exclusion of industry laggards) | Excludes companies that are deemed to have poor ESG credentials based on an in-depth assessment of a range of ESG factors. | Provides a more comprehensive and sophisticated analysis of a range of ESG factors. | Requires complex analysis and a robust and comparable ESG scoring methodology. |

| Positive screening –‘best-in-class’ approach | Focuses on companies that are deemed to have the strongest ESG credentials based on an in-depth assessment of a range of ESG factors. | Explicitly rewards industry leaders and creates a more positively aligned portfolio | Implementation would leave a very limited choice of high yield names, compromising diversification and implementation of investment-driven views. |

| Green bonds | Issued by governments or companies to raise finance specifically for “green” purposes, such as clean energy plants or energy efficiency projects. | Targets specific projects designed to make a positive environmental impact. Funds are usually ring-fenced and only used to fund the specified project. Self-selecting universe, easy to define. | Very small, concentrated universe of high yield issuers with high idiosyncratic risks. ‘Green’ designation can be somewhat subjective and inconsistent. |

| Impact investing | Covering a range of asset classes, impact investments are designed to solve social and environmental challenges. | Highly tangible. Provides capital for businesses or projects looking to make a positive ESG impact. | Opportunities tend to be illiquid, private and project-based. Can be challenging for a diversified open-ended investment vehicle offering daily liquidity. |

Responsible investing has evolved significantly over the past decade and today covers a variety of related but distinct strategies.

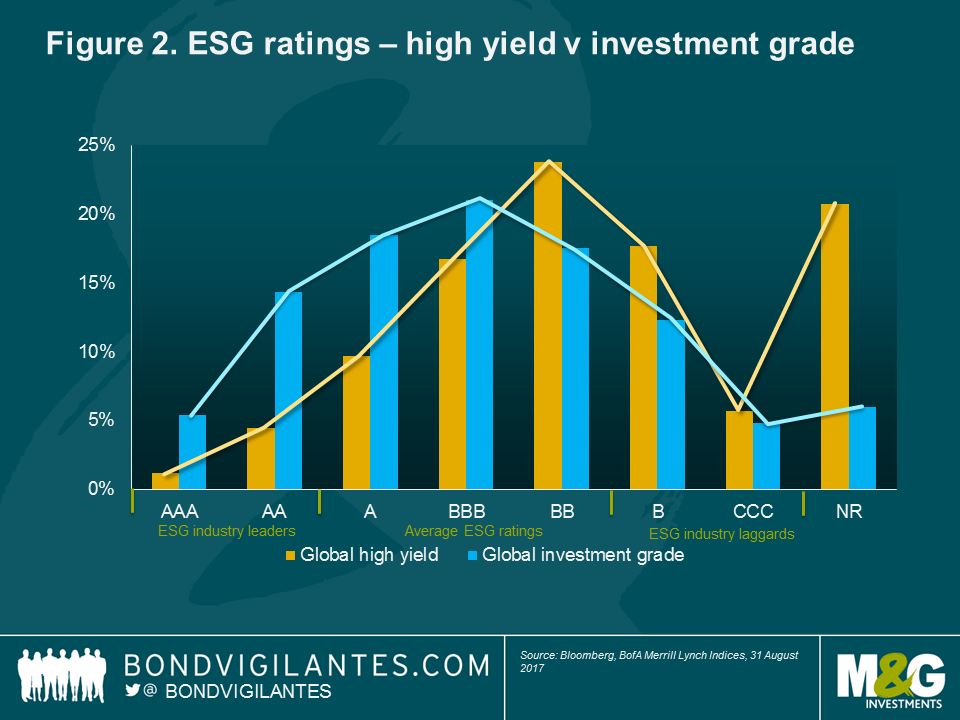

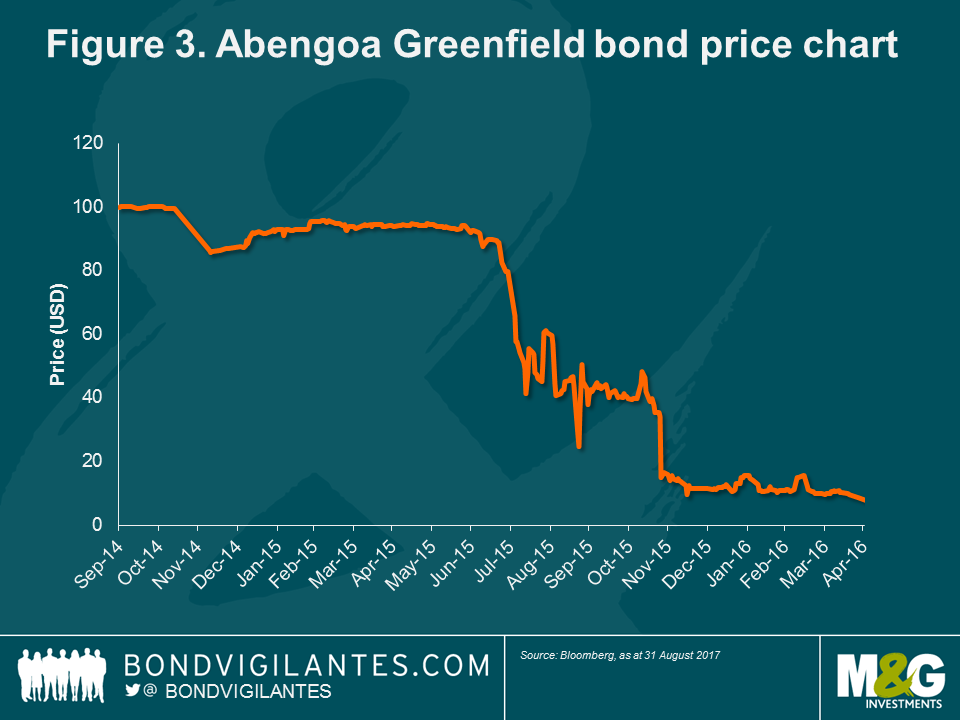

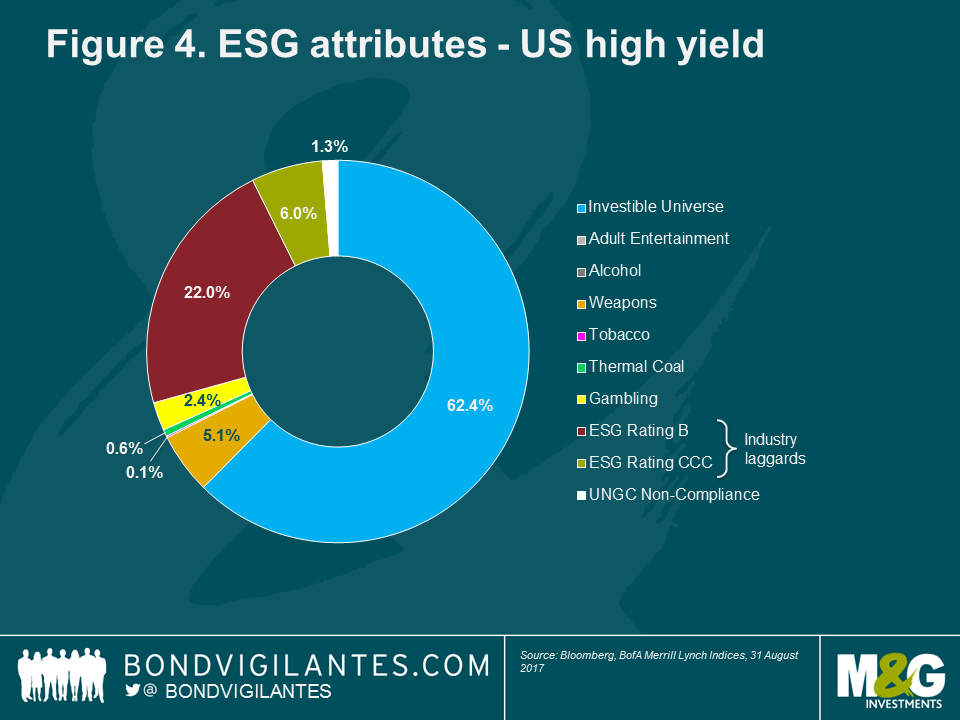

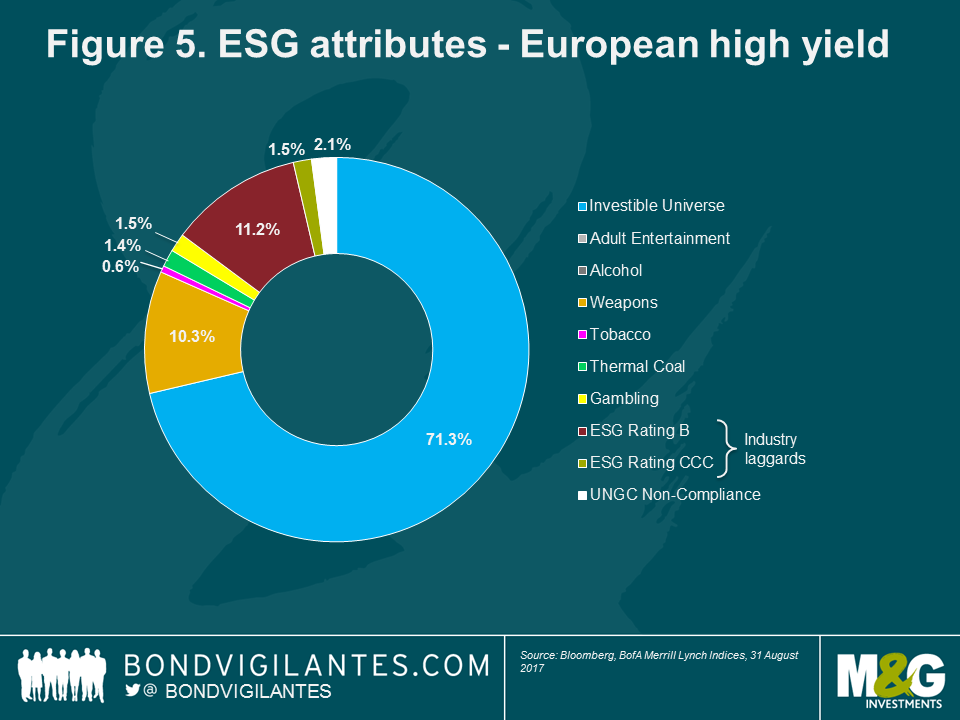

An ESG approach which has gained broad acceptance is the ‘norms’-based screen. This excludes companies that have failed to meet internationally accepted standards, such as breaching the United Nations Global Compact principles on human rights, labour, environment and anti-corruption. A ‘norms’-based screen ensures the removal of companies that have been judged to be in breach of these standards, although this approach only captures approximately 2% of high yield companies so does not provide a comprehensive ESG approach in itself.