Global bond market outlook 2016

There was, and will be, divergence

It’s not felt like it somehow, but 2015 has been a bear market for US and UK government bonds, with yields up around 20 to 30 basis points (bps) at most maturities. In stark contrast, European bonds have made new record lows this year – initially as the European Central Bank (ECB) announced quantitative easing (QE) and cut interest rates to negative levels, but again ahead of its upcoming meeting in December where further easing measures are widely expected. German bund yields now have negative yields out to six years, and even Spanish and Italian debt, pricing in high default probabilities as recently as 2012, trades with negative yields at the short end of the curve.

Elsewhere in fixed income, we’ve seen stability in most investment grade corporate bond spreads in the UK and Europe, although some event risk has come back in the market (for example, spreads in VW bonds were hit badly after the emissions scandal). US investment grade bond spreads have underperformed this year as companies issued huge volumes of debt, perhaps in anticipation of yields continuing to rise as the Federal Reserve (Fed) starts to hike rates. The US market has also seen some fundamental deterioration in credit quality: leverage has risen, partly as a result of share buybacks and mergers & acquisitions (M&A) funded by borrowing. US high yield bonds were the underperformer of 2015, continuing the damage started at the end of 2014 as energy-related bonds (rigs, pipelines, exploration and refining) started to discount a prolonged fall in oil prices. And as other commodity prices (copper, iron ore) hit their lowest levels for years, bonds exposed to metals and mining also sold off. Outside of energy and commodity names, however, default expectations remain very low.

If there was a bear market for US and UK government bonds, it was nothing compared to that in emerging markets (EM). Local currency EM debt had an awful year. The Chinese slowdown created fears for global growth, with commodity-exporting developing economies suffering as a result. As these fears rose, outflows from developing world ‘yield tourists’ exacerbated the EM debt price falls. In the local currency space, many EM government bonds now yield more than 7% (Brazil yields over 15%) When coupled with falls in currency of 20-30% against the US dollar, we go into 2016 with a significant improvement in EM debt valuations.

Talking of the dollar, as Fed rate hike expectations grew, the US currency had another very strong 12 months. As one of my highest conviction positions for the last two years, it’s time to ask whether the dollar’s valuation already reflects a world of rising US rates and slow growth elsewhere in the world.

At last – wage growth! We now know what the NAIRU is

The missing ingredient in the global economic recovery since the Great Financial Crisis has been wage growth. As economies recovered, and corporate profits grew, incomes have improved only modestly. Without consumers seeing improvements in living standards, ongoing demand for goods and services was likely to stagnate. I’ve always said that there will be a time to worry about inflation, and a time to take outright short positions in bond markets, but that time wouldn’t come until wages started to rise at a meaningful rate. As we end 2015, it’s possible that that moment is about to happen – we may be at the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment. The NAIRU.

Economists love playing the NAIRU game. Where is it? Has anyone found it? Is it higher or lower than before? Despite the elusiveness of this theoretical concept and building block of modern macroeconomic theory, the implications are wide-ranging and touch everyone earning a wage.

As the prime theory that an economy is operating at full-employment, the NAIRU is of upmost importance to central bankers around the world. Left unchecked, an environment of rapidly rising wages can lead to higher inflation as businesses look to retain profit margins by hiking prices on consumers. It is for this reason that economists closely monitor wage price developments to see if there is any sign that labour-market tightness is leading to higher wages for workers.

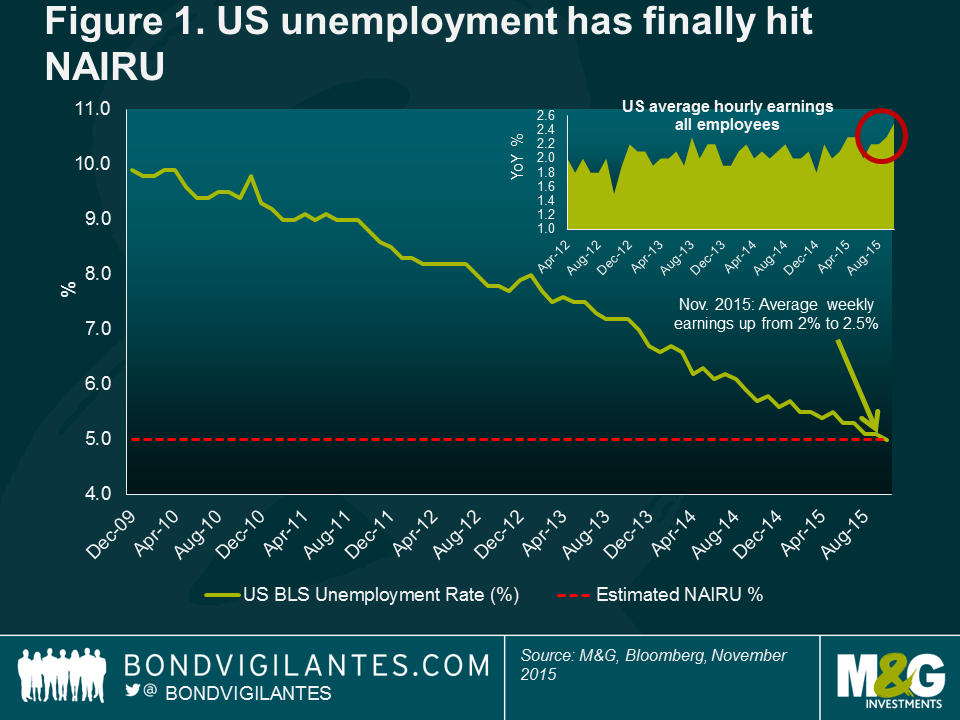

In the US and the UK, we now know what the NAIRU is. With the unemployment rate close to 5% in both countries, we have now begun to see the pick-up in wages that central bankers have been waiting for as a sign that their respective economies were on a self-sustaining growth trend (see figure 1).

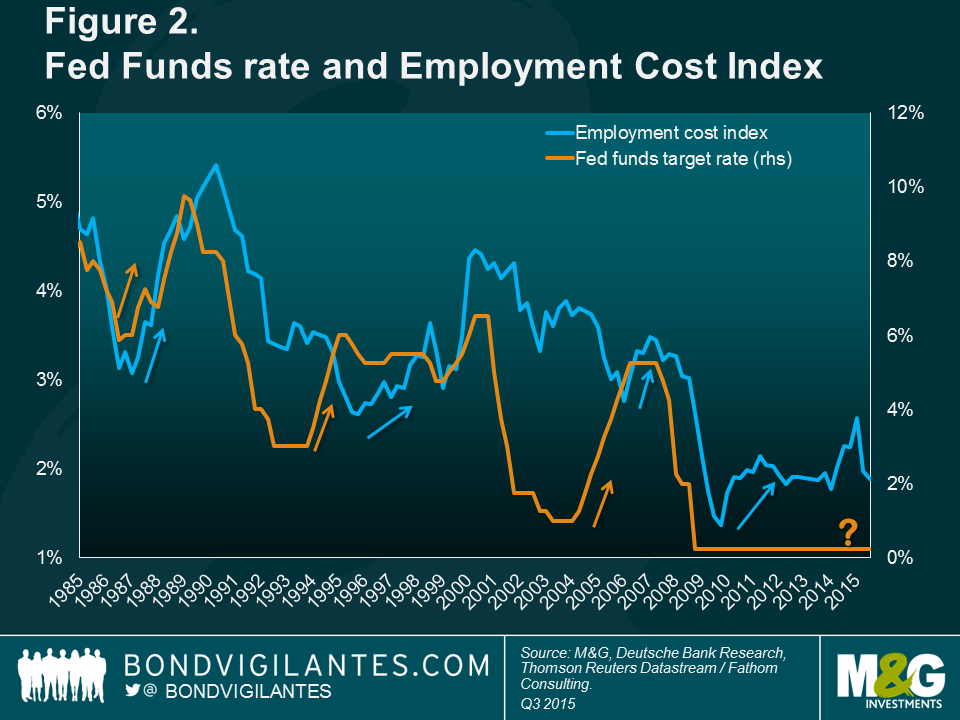

For the Fed, in particular, this is a big deal. Historically, a rising employment cost index (ECI) has been associated with interest rate hikes. Indeed, in the 1990s and 2000s, the Fed increased interest rates in anticipation of a pick-up in the ECI (see figure 2).

Given the US economy is operating at full employment, we expect the Fed is now ready – finally – to increase rates. The timing of a rate hike from the Bank of England (BofE) is more difficult to call, given the uncertainty surrounding a potential referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union (EU) in 2016. We don’t think the timing of any rate hike is as important as determining the terminal Fed Funds rate (the rate at which the Fed will stop hiking) in this cycle.

Fed tightening in this cycle will likely be unusually slow, cautious and well communicated to markets. If this is the case, then the reaction in bond markets would likely be relatively benign compared to prior Fed rate hikes. The first move of this cycle is likely to be the so called ‘dovish hike’ – rates go up, but the messaging is designed to not spook global markets. Nevertheless, historically, Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s framework for rate rises (the ‘Optimal Control’ path) suggested that the central bank’s reaction function would be to delay the first hike for as long as possible (tick) before an aggressive, steep hiking cycle. The fragilities of the global economy make this seem unlikely, but if wages continue to accelerate we should brace ourselves for a swifter normalisation of rates than is currently priced into bond markets.

Inflation: It’s all about the base (effects)

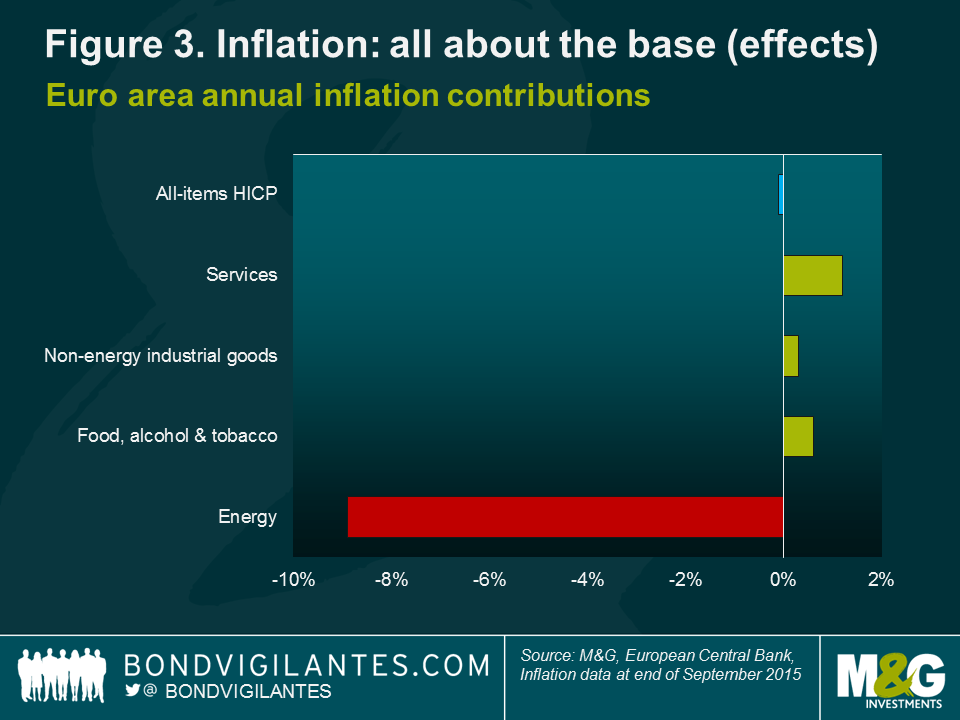

Central banks are currently doing a poor job of meeting their inflation targets, with many economies in the developed world either in or flirting with deflation. The reasons are predominantly the collapse in commodity prices, particularly oil and energy.

Energy represents 10-15% of consumer price index (CPI) baskets in developed economies, so oil price fluctuations have a significant feed-through effect on headline inflation rates (recent eurozone numbers demonstrate that the energy component of the CPI fell by 9% – see figure 3). This is particularly true in the US where relatively less tax is paid on petrol at the pump (in comparison to Europe where the bulk of the pump price comprises duty and VAT), resulting in a greater direct effect of oil price volatility on the inflation numbers.

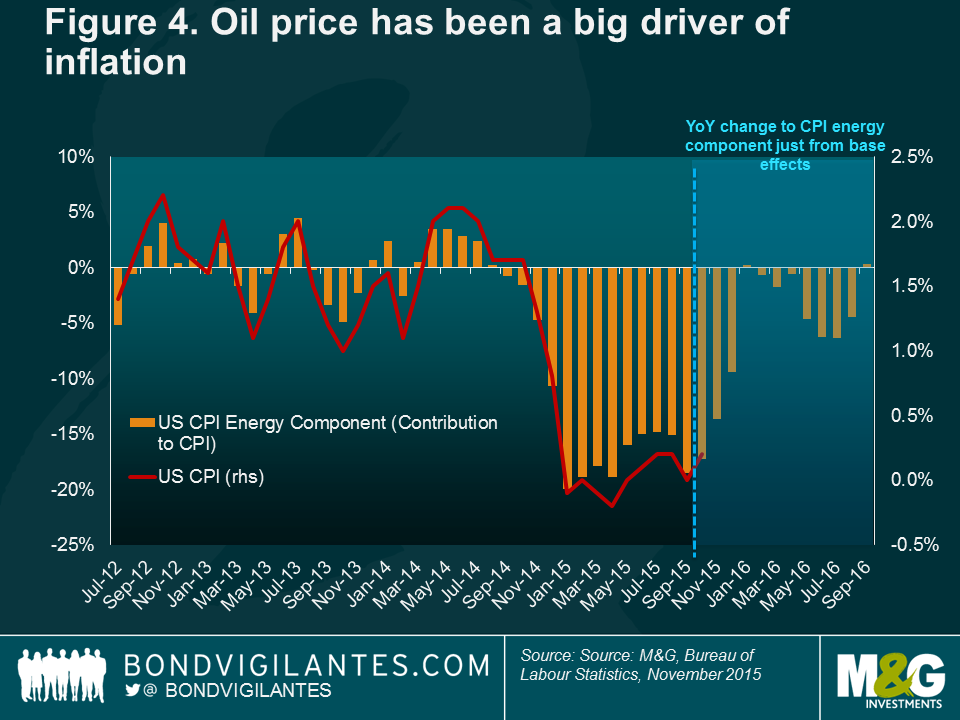

It is therefore important to remember the base effects. Base effects occur because inflation is calculated on a year-on-year basis, and therefore the movements in inflation a year ago are just as important in calculating the new inflation number as the recent movements. Because the price of oil fell significantly towards the end of 2014 and early 2015, going forward its effects on inflation are going to drop out. In figure 4, we simulate the effects on inflation in the future should the CPI energy component (of which oil is a big part) stay the same.

Though not an argument for significant inflation, or even inflation hitting its targets, this does mean that there is currently value in inflation-linked bonds across developed markets.

Welcome to Quantitative Tightening

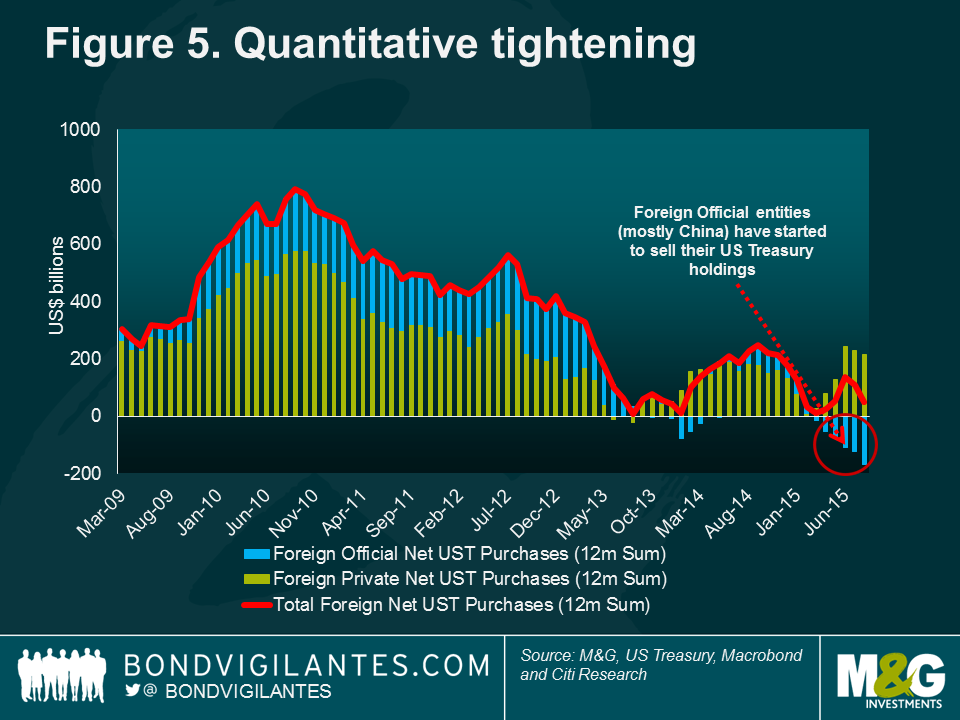

Quantitative easing (QE) is the process by which central banks inject cash into economies by buying vast amounts of government debt and other assets. This both increases the money supply, and also lowers bonds yields to reduce borrowing costs for corporates and individuals. There’s no agreement about how powerful these impacts are, but almost all estimates suggest that QE works in boosting both growth and inflation. But if QE works on the way in, what happens on the way out, when central banks stop buying bonds, and instead actually start selling down their holdings? Most of us think that large-scale selling of the QE bond holdings is unlikely (the BofE has said that sales wouldn’t commence until we’ve had a series of rate hikes to 2%), but there is another place that a quantitative tightening (QT) effect (higher yields leading to lower growth) could come from (see figure 5).

After years of stockpiling foreign currency reserves, the financial community is currently debating the impact of emerging economies turning from massive buyers to massive sellers of reserve currencies and bonds. QT is the theory that capital outflows from EM economies have resulted in large declines in foreign exchange reserves as EM central banks raised cash to facilitate a fiscal easing and to support exchange rate intervention. Because these reserves are typically held in government bonds – like US Treasuries and German bunds – this process has resulted in a surge of bond sales by EM central banks. This is particularly true in China, where foreign exchange reserves have fallen by over $500 billion in the past year as the government has been selling government bonds to control the depreciation of the renminbi.

While we should be nervous about the impact of continued liquidation of US Treasuries, gilts and bunds as EM growth remains weak, there is another powerful opposing force that continues to support the US Treasury market, in particular. Since European interest rates went negative (in the eurozone, Denmark, Switzerland and Sweden) and sent yields tumbling across the curve, investors in the region have been desperate to find attractive income-bearing opportunities. Many have fixed liabilities to match that can no longer be satisfied in the European bond markets. So capital has been gushing into the US, and so far, at least, foreign ‘non-official’ purchases of US Treasuries are outweighing the sales from the EM central banks. Even when fully hedged to remove currency risk, selling domestic bunds and buying dollar-based Treasuries results in a significant yield pick-up, with no additional credit risk. The balance of these two dynamics – QT versus European yield hunting – will be critically important for both the speed of any US Treasury sell-off and the future path of the US dollar.

A more hawkish FOMC

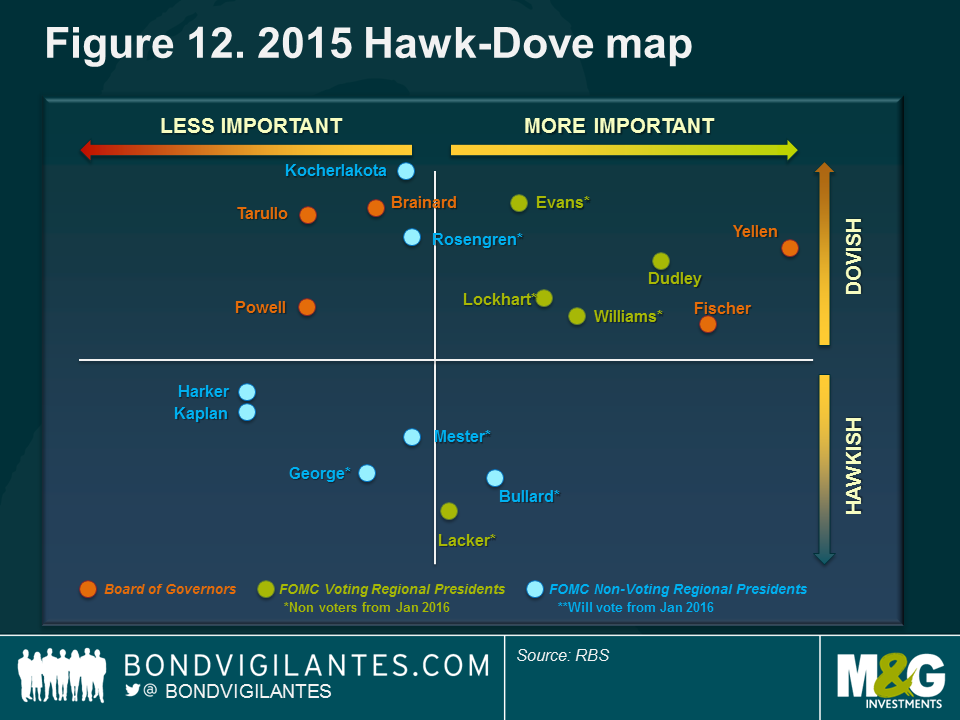

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meets eight times a year and currently consists of 10 participants, each of whom casts a single vote on the interest rate policy for the US. These voters consist of the five-person Federal Reserve Board of Governors (appointed by the US President) and five Federal Reserve regional bank presidents. Of the latter, one vote stems from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York President (William Dudley) who serves on a continuous basis and the remaining four votes originate from regional bank presidents who serve one-year terms on a rotating basis. An additional seven non-voting Reserve Bank presidents therefore attend the meetings of the committee, participate in the discussions and assess the risks to the long-run FOMC goals of price stability and full employment. All 17 members contribute to the FOMC ‘dot plot’ forecast for the path of future interest rates.

On 1 January 2016, the current four voting FOMC regional bank presidents will be rotating, replaced with four members from the non-voting pool of regional bank presidents. Heading out are presidents Lacker, Lockhart, Williams and Evans – most of whom are known for their ‘dovish’ lean and propensity to keep rates on hold given their labour market concerns. These FOMC doves are being replaced with the incoming Rosengren, Bullard, Mester and George – the latter three being some of the most vocal Federal Reserve ‘hawks’; bullish on the US economy, concerned about the inflation outlook and more inclined to raise rates sooner rather than later (see figure 12). (Although Rosengren is a dove, he is considered less dovish than predecessor Evans). On face value, one could surmise that this hawkish swing will result in a more definite and quicker pace of interest rate hikes in 2016.

No easy answer to Europe’s problems

What’s a central bank president to do? Having averted the eurozone crisis with his famous “whatever it takes” speech in 2012, and convincing the more hawkish members of the ECB Governing Council to embark upon QE to the tune of €1.1 trillion this year, ECB President Mario Draghi continues to desperately seek an answer to the deflationary malaise in which the economy currently finds itself. In November this year, Draghi told markets that the ECB “…will do what we must to raise inflation as quickly as possible. That is what our price stability mandate requires of us.”

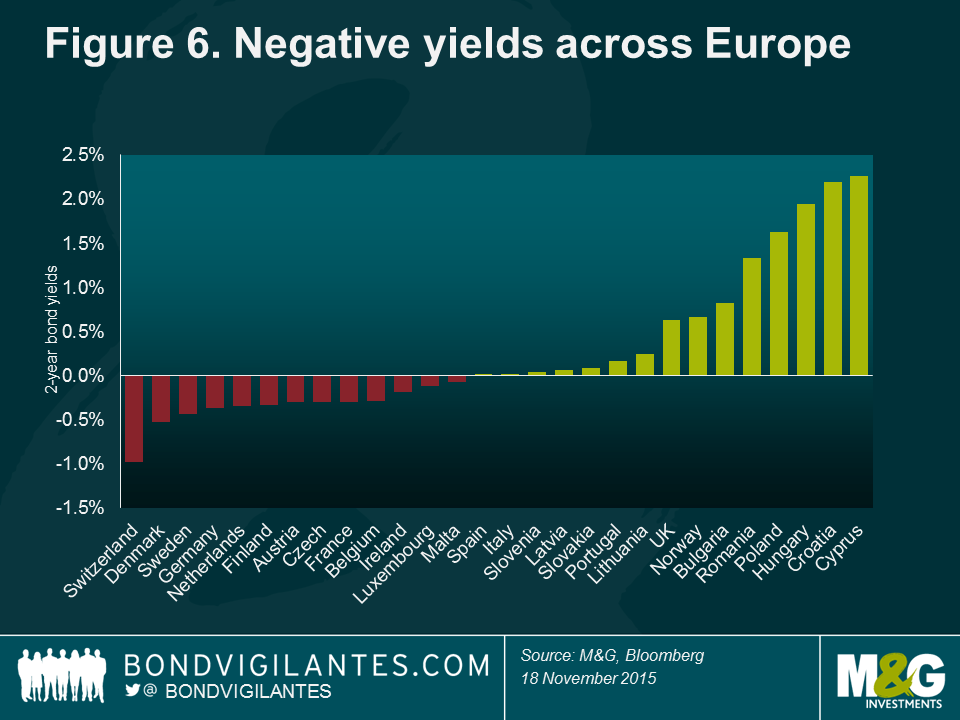

There is widespread speculation that the ECB will undertake further easing measures in order to deliver on its price stability mandate of close to, but below, 2% inflation. These include expanding and extending its asset-purchase programme, adding to the composition of asset classes that are eligible for ECB purchases, as well as cutting interest rates further into negative territory. Previously, Draghi said that “we are at the lower bound”. This appears premature; the central banks of Switzerland, Sweden and Denmark have all maintained negative interest rates into 2016 (see figure 6). There is no reason why interest rates could not go deeper into negative territory.

With the ECB likely to lower its forecast for economic growth in 2016-17 and given the extent of monetary easing that has already taken place, it is clear that the eurozone economy is not in a healthy state despite signs of improving consumer confidence. Concerns around the possibility of Greece leaving the eurozone, political risk in Spain and Portugal, and a lack of any real progress towards a fiscal and political union are likely to continue to weigh heavily on investors’ minds in 2016 and beyond.

The trends evident within the European macroeconomic landscape have several implications for investors. Firstly, the euro is likely to come under further pressure given the different policy biases of the ECB and the Fed. A gradual decline in the euro may result over the course of 2016, with parity to the US dollar a potential reality. A negative ECB deposit rate and higher Fed Funds rate is at the core of this prospect as capital flows out of the euro area in search of a positive return.

Secondly, ECB action is likely to support the front end of the yield curve in the short term and may see support for yields with longer-term maturities. However, we see little value in owning European government bonds at these low yield levels, given the risk of an upward surprise in inflation rates and limited potential for upside capital returns. Indeed, with a third of the European government bond market trading with a negative yield, it seems preposterous to lock in a negative return unless you believe that Europe is entering into an economic depression.

Thirdly, European corporate assets – like asset-backed securities and corporate bonds – may increasingly come into scope for ECB asset purchases as it attempts to encourage banks to lend into the real economy. In this type of environment, high-quality corporate bonds may be the biggest beneficiary of a large buyer like the ECB stepping into the market.

Finally, a further cut in ECB deposit rates could have a negative impact on bank profitability as net interest margins are further squeezed by lower interest rates. There are also fears that domestic lenders in Spain could be forced to pay billions of euros in compensation to customers whose mortgage contracts were found to have illegal interest rate floors. Additionally, life insurance companies face further pressure in an environment where it is difficult to generate positive real yields from risk free assets.

Better valuations in corporate bonds

There are two significant supports in place for credit markets as we go into 2016. First of all, credit spreads in both investment grade (IG) corporate bonds and in high yield (HY) are likely to overcompensate for expected default rates (so hold-to-maturity credit investors are likely to outperform investments in government bonds); secondly, in a world of low or negative yields in government bonds, investor demand for credit remains firm.

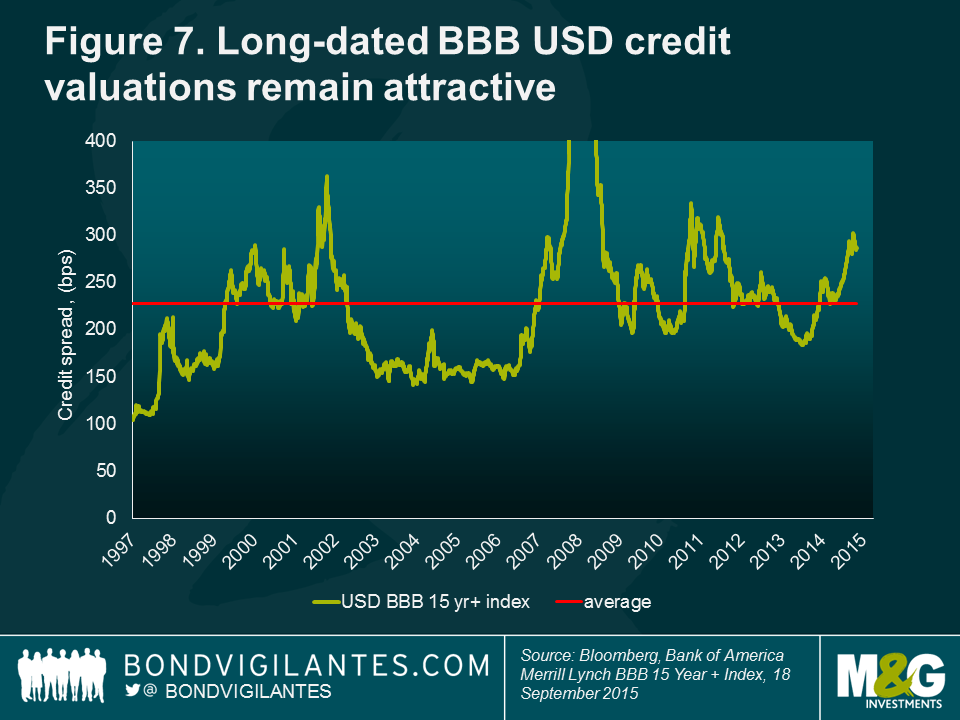

In particular, we think there’s some excellent fundamental value in long-dated US BBB rated bonds, where we can find spreads of 250-300 bps over US Treasuries in companies we like (see figure 7).

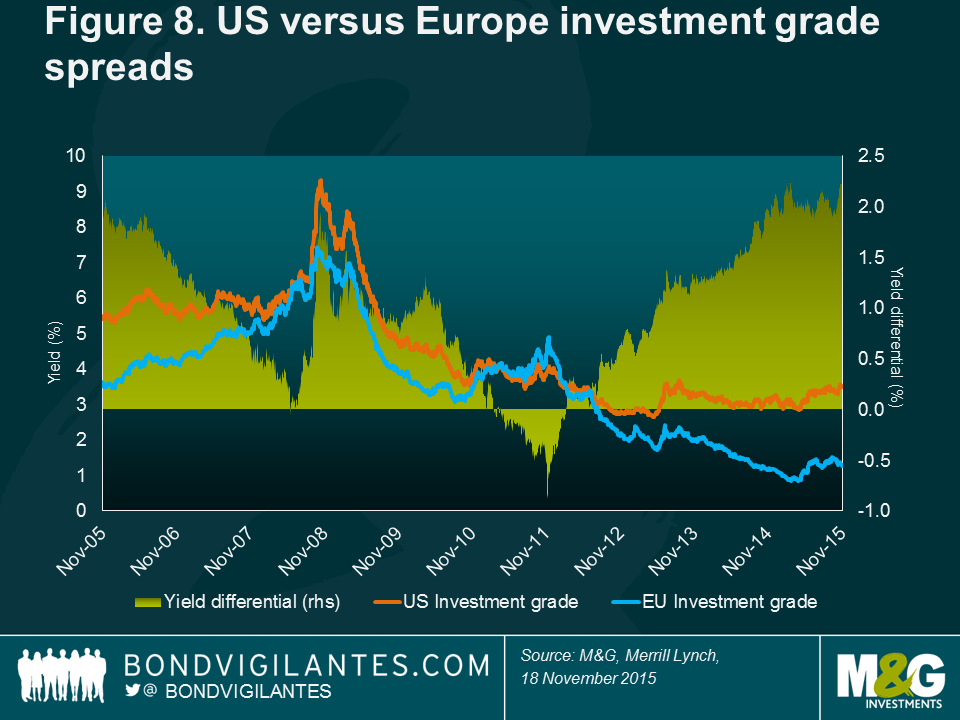

US investment grade underperformed in 2015 due to the weight of issuance there as companies anticipated the start of the Fed hiking cycle. As a result, the pick-up in yield over European investment grade debt is now over 2% at the index level (see figure 8).

While there is a perception that credit is expensive, it’s worth noting that over the past 20 or so years global corporate bond spreads have been tighter than they are now 73% of the time and, after the widening in spreads we saw in August and September, my global bond strategy was to add credit risk, both in investment grade and high yield.

This doesn’t mean that there aren’t challenges. We think a good portion of the ‘overcompensation’ that credit investors get for investing in the asset class isn’t about credit risk, but liquidity risk. There were a couple of days in 2015 when credit markets all but closed down as risk appetite disappeared. Managing liquidity risk in a portfolio is equally as important as choosing the companies you lend to: this might mean running with more cash or government bonds than you might like ideally, it might mean avoiding smaller or complex bond issues, and the use of credit default swap (CDS) indices is important as an extremely liquid way of adding or removing credit risk from a fund.

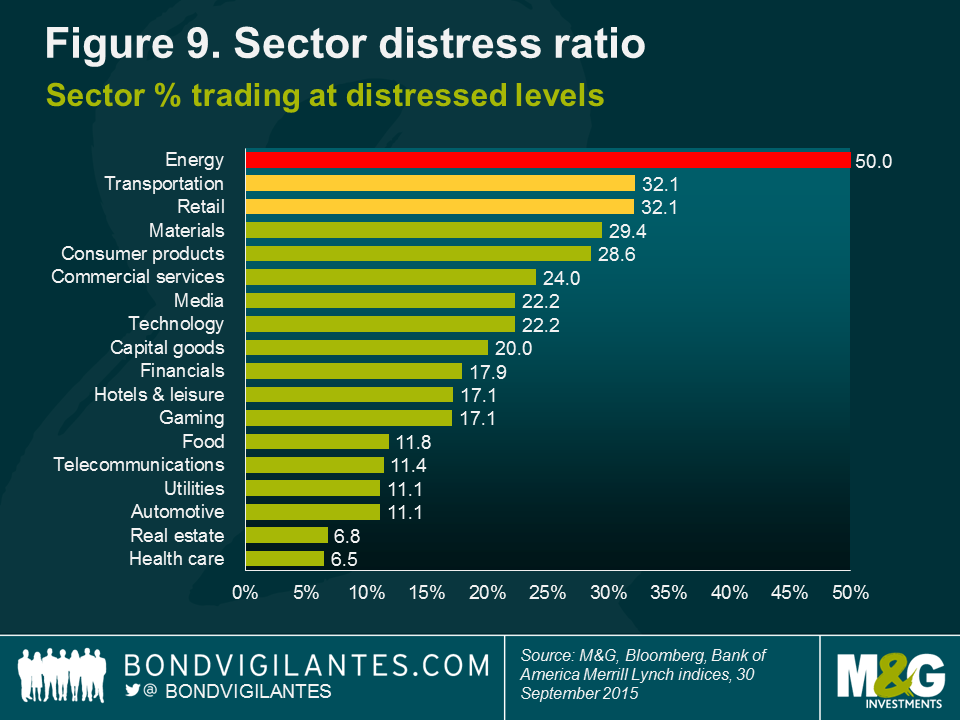

Other challenges relate to increasingly poor behaviour from corporate bond issuers. For example, bond investors don’t like debt-financed M&A that results in ratings downgrades, or bonds being issued to do share buybacks (or to buy the business owner a third yacht). This kind of issuance is coming back to the market, and corporate leverage is edging up. So the tailwinds of improving corporate fundamentals are no longer with us, and there’s also been a pick-up in idiosyncratic risk (the VW emissions scandal, for example, which saw its 10-year bonds fall by around 10%) and a sector-specific pummelling: high yield energy bonds have seriously underperformed as the oil price collapsed (see figure 9), with many bonds now priced at distressed levels (commodity names, like Glencore, suffered as well). Defaults will pick up from the 2.5% global high yield annual rate, but with high yield spreads at 6% over government bonds there is room for the asset class to outperform.

Fear and loathing in emerging markets

Emerging Market (EM) countries have been an important source of economic growth since the financial crisis of 2007-09. Initially, it was the huge fiscal stimulus, particularly in China, that gave global trade and activity a lift. More recently, it has been a significant leveraging of EM corporate balance sheets that has helped to support growth. In 2015, these factors began to diminish, resulting in lower global growth and turmoil in many EM asset classes.

EM assets were hit by a number of key events throughout 2015. The unwinding of a multi-year bull market for commodities has been damaging for even those countries that would have normally benefited from lower input prices. For example, Turkey should have been a huge beneficiary of lower oil prices, as oil imports represent roughly 60% of the country’s trade deficit. Yet, a toxic combination of geopolitical worries and policy mistakes overwhelmed Turkey’s sovereign balance sheet improvement. In Brazil, the currency plummeted after a corruption scandal and continued wavering on economic reforms by President Dilma Rousseff. Turning to Asia, the region has suffered negative growth spillovers from China, resulting in a slowdown in trade within the region.

We have held back from investing in EM assets over the past few years, waiting to see what impact a slowdown in Chinese growth would have on EM bonds and currencies. Additionally, we observed that companies in EM economies were gorging on cheap foreign currency funding since the Great Financial Crisis and credit valuations, in particular, appeared expensive to us. EM economies now face rising credit costs, slowing bank earnings, decelerating credit growth and weaker economic performance. Particularly worrying was the impact that higher US interest rates and weaker domestic currencies would have on the ability of sovereigns and corporates to meet their debt obligations. In this environment, EM companies with structural advantages, like low dollar-denominated debt and strong currency hedging practices, are likely to perform better than their peers.

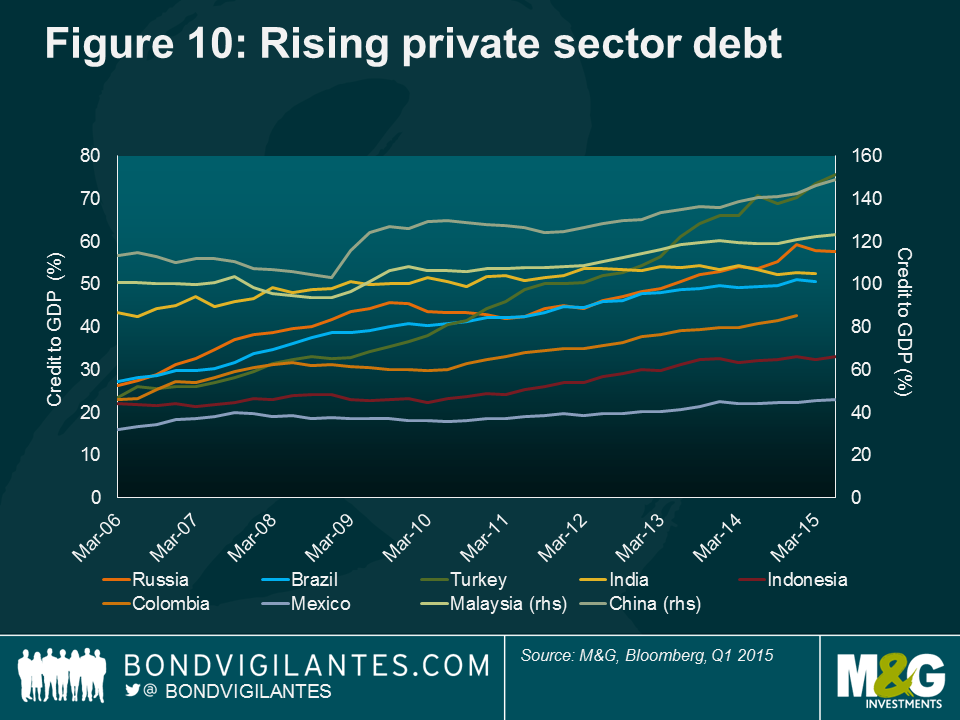

One mitigating factor could be EM currency reserves, but we note that these now appear to be falling. Also, an important distinction between the 1990s and early 2000s is that the build-up of private sector debt (compared to public sector debt previously) means that the risk of default is now more spread out (see figure 10).

The impact of foreign remittances as workers employed in the large developed world economies send money home to their families was another positive for EM. But from a trading standpoint, the memory of prior EM episodes could continue to restrain risk-taking in EM markets. Any further reversal of capital flows, especially portfolio investment, could continue to reduce the ability of spreads to compress in 2016. While EM has witnessed significant outflows since the 2012 ‘taper tantrum’, reducing the risks of a wholesale exodus, there are still significant risks of further capital flight.

Despite these worries, the tough environment for EM assets in 2015 means that EM valuations are now not as rich as they once were. Emerging economies have been better managed over the past decade and monetary policy is more credible, inflation expectations are better anchored, banking systems are more robust and financial regulatory and oversight has improved. Nonetheless, the two massive elephants in the room – foreign currency liabilities and capital flight risks – present significant tail-risk scenarios for EM. How these risk factors evolve will be a key factor in our determination of the appropriate time to increase exposure to EM bonds and currencies.

Divergence and the dollar

Since the middle of 2014, the US dollar index is up by nearly 25%. The dollar’s safe-haven status in a world of renewed geopolitical tensions (Ukraine, Syria), and the economic weakness spreading from China to the rest of the emerging markets explains some of this appreciation. But the rest can be explained by what might be the financial ‘Word of the Year’ in 2016: divergence. Rates are not only likely to rise in the US during 2016, but for the eurozone, Japan and those emerging economies more monetary stimulus rather than less is likely.

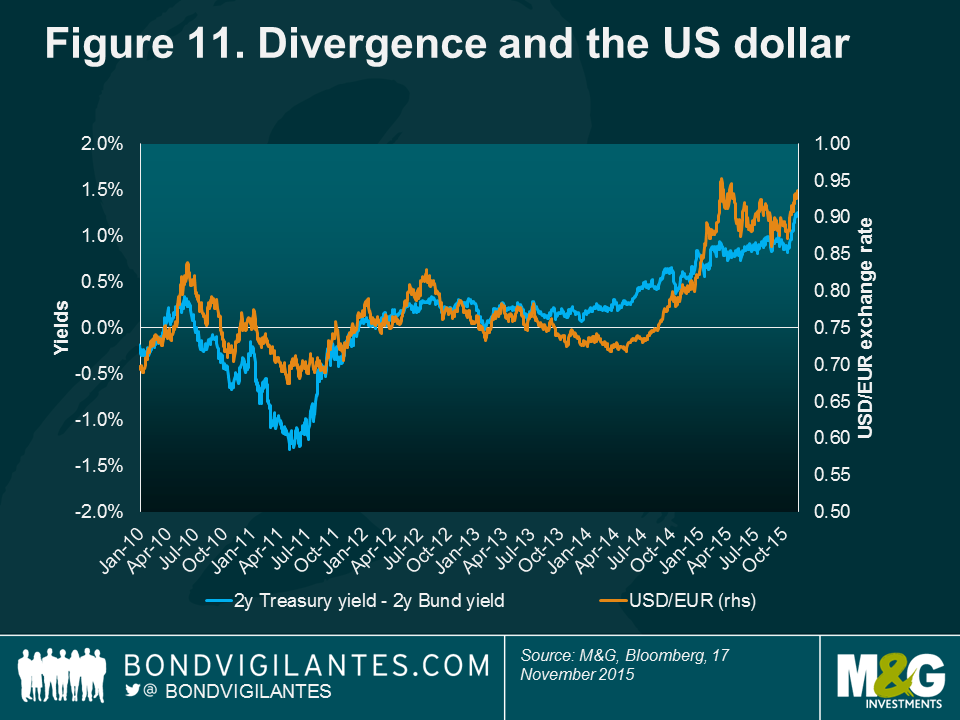

In January this year, two-year US Treasury bond yields were at 0.4%, and those in Germany were at -0.1%, a spread of 50 bps (see figure 11). As we move towards the end of 2015, the bond markets are pricing in rate moves in opposing directions, with a 70%+ chance of a December Fed hike now discounted, and the ECB expected to cut its deposit rate down to negative 35 bps. The spread between the two-year yields in the US and Germany is now over 120 bps, making Treasuries look much more attractive and encouraging capital flows into US assets and the dollar.

European rates are expected to be negative for at least two years, by which time markets think the Fed will be approaching a 2% funds rate. As a result, both investment and speculative flows into the dollar have increased, perhaps to a level that might limit the potential for future appreciation (a recent investment bank survey showed that long dollar positioning was believed to be the most ‘crowded’ trade in global financial markets). We remain positive on the US dollar, although following the steep falls in emerging market and related currencies (such as the Australian and New Zealand dollars) we have closed out many of our short positions against the greenback.

As divergence continues, we would expect the euro to continue to underperform; but we’re likely to be nearer the end of these currency movements than the beginning. History shows us that the bulk of a cyclical dollar rally occurs in the run-up to the first Fed hike, and some of the fundamental valuation methods for the US currency now don’t make it look so stellar. Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) looks at the relative currency-adjusted prices of goods in different economies and suggests that there should not be significant differences across geographies and they should be able to be arbitraged away. Practically, PPP differentials can persist for long periods thanks to imperfect markets and structural differences, but there is evidence of long-term mean reversion. PPP now has the dollar looking expensive against most other currencies (The Economist’s PPP proxy, the Big Mac Index, has only Switzerland and the Nordic currencies as overvalued versus the US dollar). Other valuation methodologies that look at inflation-adjusted trade balances (Real Effective Exchange Rates) also show the dollar to be dear. At the other end of the scale, despite a perception that it’s a furiously expensive place to visit, the Japanese yen is cheap.

We mustn’t forget also that if the dollar continues to strengthen it will do the Fed’s job for it. Monetary conditions have tightened as a result of the trade-weighted dollar appreciation (although the US is a relatively closed economy, so the impact isn’t as big as it would be for the UK, for example, where we are addicted to imported goods). The pain of the strong dollar has been felt predominantly in the corporate sector (a Fortune magazine headline from October reported: “American companies are in a profits recession: You can blame King Dollar”). US earnings per share fell in the second quarter and are expected to have fallen in the third quarter too, as overseas revenues shrank in dollar terms. In the 1980s, the US dollar appreciated by around 50% against the pound, Deutschmark, French franc and yen, leading to the Plaza Accord in 1985. As calls for protectionist policies grew from US companies and politicians, global central banks met to successfully coordinate a devaluation of the dollar. It doesn’t feel like we’re anywhere near that point yet – and maybe the US can best afford to be the sole ‘loser’ in the currency wars?

What will we do when robots take our jobs?

Cleveland, 1954. Henry Ford II was showing the head of the auto workers’ union around a new semi-automated Ford car factory and cheekily asked him who would be paying union fees in the future. The union boss replied, “and who’s going to be buying your cars?” This apocryphal story encapsulates the two fears that have taking robotics out of the pages of the New Scientist and into those of The Economist. Firstly, that technology is advancing so rapidly now that robots are “eating our jobs” – and, whereas historically robots replaced tools, they are now replacing workers and increasingly moving up the skills curve. Robots and Artificial Intelligence (AI) no longer just do routine assembly work, but are replacing higher skilled workers in areas like medicine, education and the law. Whilst technology also creates jobs, the start-up success stories of recent years (eg, Google) have extremely small workforces. Secondly, as robots replace higher paid workers, the aspirational middle classes suddenly find themselves unable to buy the ‘stuff’ that keeps our modern economies going. Consumption falls and a deflationary spiral begins. In The Rise of the Robots, Martin Ford’s brilliant book about this process, he suggests that even better education won’t save the next generations from being replaced by machines. To prevent social disaster and economic collapse, we therefore need to consider a guaranteed income for all citizens.

Elsewhere, technology is starting to affect fund managers in other ways. For example, in the last few weeks we’ve been offered satellite analysis of retailers’ car parks to help forecast their sales, and CO2 data from China as a ‘nowcast’ of GDP growth there. The Billion Prices Project scrapes internet data to generate a daily CPI number that tracks the official number (released a month later) pretty well. A company tried to sell me a high-speed internet connection to the ECB’s press conference that was claimed to be several seconds quicker than the mainstream broadcasters’ feeds. This exponential technological progress is already transforming our understanding of the global economy.

The brave new world of Modern Money Theory & People’s QE

In a blog in April 2012, I suggested that a relatively painless way to reduce the UK’s ever-expanding debt burden might be to ‘cancel’ the gilts held on the Bank of England’s balance sheet as part of the QE programme. It’s fair to say that there was some robust pushback from readers (although not as much as I got when writing about Scotland, or electronic money…). Fast forward to today, and this seems like it might be an idea whose time has come, although I’d argue that with the UK economy growing again the need for such extreme measures is much lower now.

But others disagree. There’s a growing academic movement that suggests that a bonfire of both public and private sector debt is urgently needed. And money printing is back in fashion. Modern Money Theory (MMT) suggests that no government that can print its own money should ever find itself fiscally constrained. At times of economic stress, governments should actively create ‘fiat money’ to spend on projects that create full employment. Mass unemployment need not be tolerated. Don’t worry, because resource constraints rather than the money supply cause inflation.[1] Linked to this idea, and central to the ideas of Adair Turner (who has also subsequently called for the cancellation of the QE gilts) in his new book Between Debt and the Devil[2], is a criticism of bond market-funded credit expansion via the banking sector. And as the Bank of England discusses unwinding QE (it will do so when rates in the UK hit 2%), new Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn has said that his government would introduce ‘people’s QE’, with printed money financing infrastructure projects and increased government spending.

While it doesn’t feel as though the UK or US have passed the point where money printing is needed (Europe and Japan on the other hand…), we do need to look at the ever-increasing stocks of both public and private debt in the developed world and ask ourselves whether either economic growth or inflation will naturally erode them. If not, then default, restructuring, or the printing presses may eventually come into play.

[1] For my recommended read on this, see Modern Money Theory: A primer on macroeconomics for sovereign monetary systems, by L. Randall Wray, Palgrave Macmillan, August 2012.

[2] Princeton University Press, October 2015.

Positioning for 2016

A central bank policy member told me recently that, “the least likely path of monetary policy is that priced in by bond markets”. The US interest rate futures market expects a gradual pace of rate hikes towards 2% over the next couple of years. This policymaker’s view was that growth and inflation outcomes are likely to be binary. The inflation soft patch we are in now could be symptomatic of deep problems in the global economy, in which case further monetary easing and unconventional policies will be needed. Or, if the recent wage developments are maintained, inflation could return to target sharply, and rates will need to rise much more quickly than the market expects. We think it’s more likely that we have reached full capacity in many areas of the labour market in the US and UK, and that there is little value in their government bonds.

If we’re right, and recent wage inflation is sustainable, then we should see inflation rates heading back above 1% in the developed economies. A return to CPI levels above central bank 2% targets will take longer, but with inflation-linked bonds pricing in persistent disinflation, we want to buy them. Insurance is a better buy when it’s cheap, and inflation protection is no different.

In corporate bonds, it’s hard to see why default rates should rise much from current levels. Fundamentals are slowly deteriorating, but outside of energy and commodity names, spreads appear to overcompensate investors for the credit risks they take. Liquidity risks remain high though, as the corporate bond market asset growth has been accompanied by a shrinking of the investment banks’ ability and willingness to hold bonds on their balance sheets. We believe investors need to be compensated for both credit and liquidity risk, and to run more in cash and liquid fixed income instruments than they might want to purely from an investment standpoint.

The sell-off in emerging market debt and currencies looks to be the biggest valuation opportunity in global fixed income. Significant risks remain, however, both from the continued slowdown in global trade, but also from domestic politics and fiscal deterioration. We’ve closed out our EM short positions, but are not yet ready to be fully bullish on the asset class.

The dollar tends to do well until the Fed starts its hiking cycle. While the strengthening of the US currency is relatively modest compared to some of its previous bull cycles, and we expect it to continue to outperform into next year as the great ‘divergence’ continues, on some fundamental valuations, and taking into account heavy investor positioning in it, the upside potential is not as great as it was.

Brexit could have a big impact on UK assets

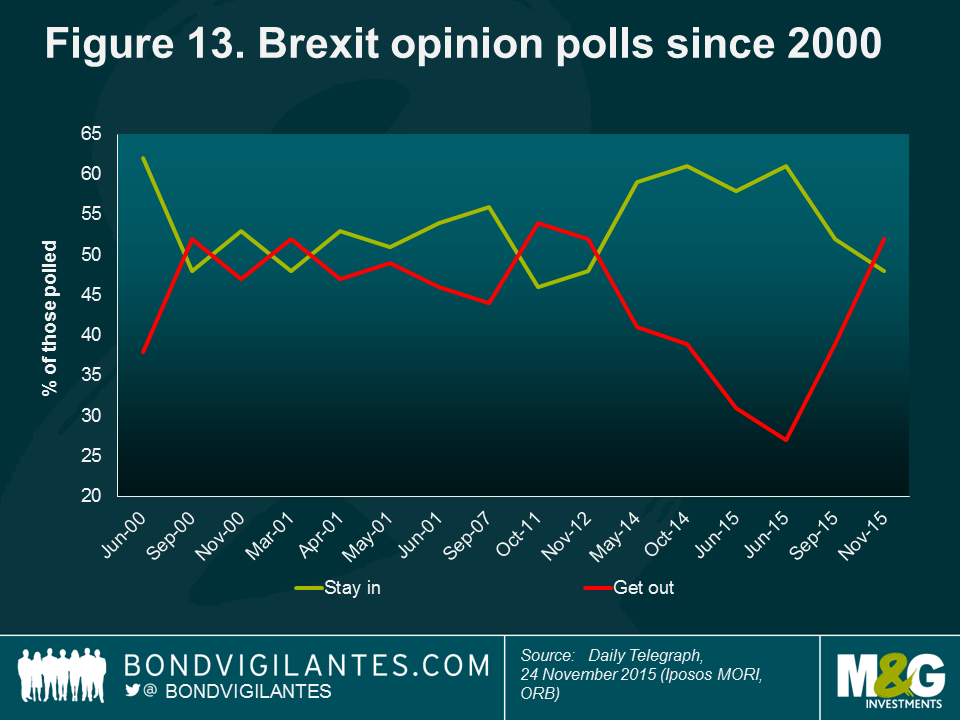

2016 could be the year that the UK votes to leave the European Union. Prime Minister David Cameron has said that an In/Out referendum on membership will take place by the end of 2017, and many expect the vote to be held during 2016. Whilst opinion polls during much of 2015 supported the ‘stay in’ vote, the latest data suggests that the majority of responders would now like to ‘get out’. Ongoing economic problems in the eurozone, and perhaps most importantly the perception that Europe’s open borders encourage UK-bound immigration, have recently reversed the tide in favour of Brexit (see figure 13).

Would Brexit matter? Eurosceptics point to the fact that European companies need the UK more than the UK needs them, given that Britain is a large net importer from the eurozone. They also point to the success of non-EU European states such as Switzerland and Norway, which have free trade agreements with the Union. But with a third of the UK’s gilt market owned by foreign investors, a record current account deficit needing to be financed, and ratings agency Standard & Poor’s suggesting that a two-notch downgrade would follow a Brexit vote, it’s difficult to be too relaxed about the impact of an ‘Out’ vote. The pound has been strong in 2015, largely thanks to rate hike expectations, but it’s probably rational to be nervous about UK assets as the referendum date nears.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox