A growing asset class

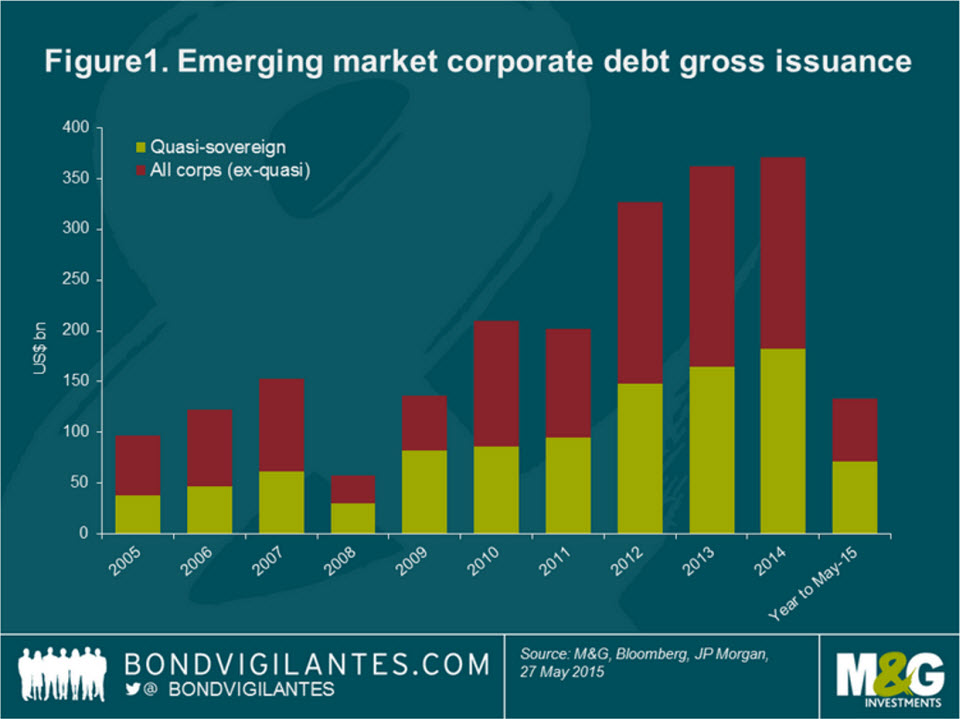

Emerging market (EM) corporate debt has been the fastest-growing segment of fixed income assets over the past decade, rising by nearly seven times since 2005 with external EM corporate debt currently worth c.US$1.7 trillion – larger than the US high yield credit market. One significant contributor to this growth in EM corporate debt in recent years has been the increasing share of quasi-sovereign issuance, which accounted for 49% of the US$371 billion of bonds issued in 2014 (see figure 1). Helped by this trend, EM quasi-sovereign bond stock of US$783 billion surpassed EM sovereign-only bond stock of US$747 billion in 2014 for the first time.

While the definition varies across market participants, an entity or a company is typically defined as ‘quasi-sovereign’ if a government owns either more than 50% of its equity or more than 50% of the company’s voting rights.

Historically, developing countries have been using quasi-sovereign issuance to fulfil policy function, develop the hard-currency corporate debt market, or promote international expansion of leading domestic players. As at the end of June 2015, there were about 170 quasi-sovereign issuers in emerging markets*, more than 60 of which were fully owned (such as Petróleos Mexicanos, or Pemex, in Mexico) or issued bonds explicitly guaranteed by their respective governments (for example, Magyar Exim Bank in Hungary).

* Estimate based on various EM bond indices.

Given the commodity-based nature of emerging markets, oil & gas is unsurprisingly the most represented sector within the quasi-sovereign bond universe, followed by financials, utilities and metals & mining.

In terms of countries, China has been by far the largest issuer of quasi-sovereign debt in the past five years, with over US$170 billion of hard-currency bonds currently outstanding. Following this market in absolute size are Russia, Brazil, Korea, the UAE and Mexico. However, on a relative basis (measuring quasi-sovereign bonds as a percentage of total hard-currency bond stock of a country), Venezuela, several Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members (namely United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Saudi Arabia), and Kazakhstan, are ahead of Russia and Korea, and even China.

The largest single issuers are Latin American oil & gas giants Pemex and Petróleo Brasileiro (Petrobras), which altogether represent nearly 15% of total quasi-sovereign bond stock in emerging markets (see figure 2).

One of the best risk-adjusted returns in EM

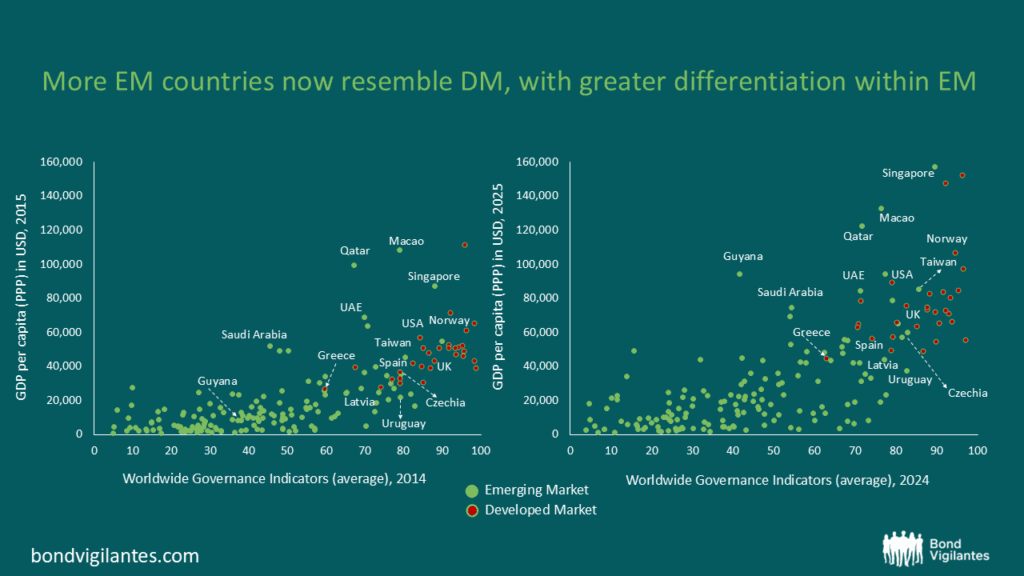

EM quasi-sovereign bonds have generated good returns since 2005. According to JP Morgan, they generated an annualised return of 6.05%** between 2005 and 2014. With a Sharpe ratio of 0.51 during the same period, this sub-asset class has delivered the best risk-adjusted return within EM (hard-currency) debt over the past decade. The good returns coincided with a prosperous period for emerging markets, characterised by improving macroeconomics in developing countries and relatively healthy fundamentals in the ever-growing corporate debt universe. However, times have arguably changed for emerging markets and macro headwinds have resurfaced in the likes of a stronger US dollar, low commodity prices, fears of a hard-landing for the Chinese economy and EM outflows on the back of the long-awaited US interest rate hike, amongst others.

**Evolution of Quasi-Sovereigns in the EMBI Global, JP Morgan, February 2015

Against this backdrop, an important impact for quasi-sovereign credits has been the increasing differentiation made by investors in terms of corporate fundamentals – an analysis that was somehow lacking, based on the assumption that sovereign analysis was sufficient and that quasi-sovereign corporate fundamentals almost did not matter.

Assessing the credit risk of quasi-sovereign issuers

In most instances, a quasi-sovereign usually has a so-called ‘implicit’ guarantee from its government, but that does not mean it will necessarily obtain an ‘explicit’ guarantee on its bonds. Therefore, bond investors must make sure they carefully examine bond documentations to assess whether or not they are invested in a bond explicitly guaranteed at the sovereign level. For example, while SriLankan Airlines, the national carrier, has weak credit fundamentals, its bonds are nevertheless rated B+ by Standard & Poor’s, in line with Sri Lanka’s government rating, because of the unconditional and irrevocable (hence, explicit) guarantee offered by the government on SriLankan Airlines’ bonds. A change of control clause is also critical in assessing the level of protection for bondholders to a change in the government ownership. Again, credit documentation due diligence is required to identify these risks.

Another key element for assessing quasi-sovereign risk is the level and likelihood of government support in case of liquidity woes. The more strategically important a corporate is to a country, the more likely a government will be supportive. This is the reason why there is a wider definition of quasi-sovereign – albeit less used by market participants – which includes privately owned companies that are of extreme importance to the economy and would likely be supported by their respective governments. This is the case, for instance, with privately owned Alfa-Bank in Russia. On the contrary, a high level of government-ownership does not necessarily mean that a government will be supportive in a default scenario; therefore, assessing the willingness – on top of the ability – of a government to step in is crucial. As an example, in 2009, the state-controlled Dubai World conglomerate ran into financial trouble and the government of Dubai clearly stated at this time that it had no legal obligation to financially support the company, adding that: “the lenders should bear part of the responsibility”. What was seen as a safe quasi-sovereign investment finally resulted in a painful and lengthy restructuring of the debt for bondholders.

The third factor in quasi-sovereign risk assessment is, of course, corporate credit risk. This encompasses the same work as for ‘pure’ EM corporates – that is, sector outlook, operational performance, credit metrics, management analysis, foreign exchange mismatch, refinancing risk analysis, covenants, bond recovery rate estimates in case of default, etc – in order to measure the so-called ‘standalone credit profile’ of an issuer. Good practice consists of assessing a standalone rating of the intrinsic credit, excluding extraordinary support of a government in a default scenario, but including any daily or punctual government support in the daily operation of a company. Brazil-based quasi-sovereign Petrobras, for example, is rated Ba2 by Moody’s, which assumes a high likelihood of government support (Brazil is rated Baa3 by the rating agency), but is only rated three notches below at B2 on a standalone basis (baseline credit assessment), following the deterioration in Petrobras’ fundamentals and the ongoing corruption scandal involving the company.

How quasi-sovereign bonds trade

To understand how EM quasi-sovereign bonds trade in the market, one important distinction investors make is the aforementioned level of government ownership and the presence or not of government guarantees, as the correlation of a quasi-bond to its sovereign component is highly dependent on these two elements. In general, spreads of quasi-sovereign issuers that are explicitly guaranteed or 100% owned by their governments are highly correlated to their respective sovereign spread. For example, this is the case for PEMEX (100% owned by Mexico) or oil & gas group Pertamina (100% owned by Indonesia), whose spread correlations with their respective sovereign bonds are 0.93 and 0.95. Bond indices, in general, make a case of this correlation and JP Morgan includes fully owned or explicitly guaranteed quasi-sovereigns in its EM hard-currency sovereign index (EMBI Global). The EM hard-currency corporate bond index (CEMBI) includes most quasi-sovereign issuers that are not 100% owned or not explicitly guaranteed by their respective governments. These latter bonds typically have a lower correlation to their sovereign curve, although the sovereign spread component is not negligible – for instance, Petrobras spreads have a correlation of around 0.5 with Brazil.

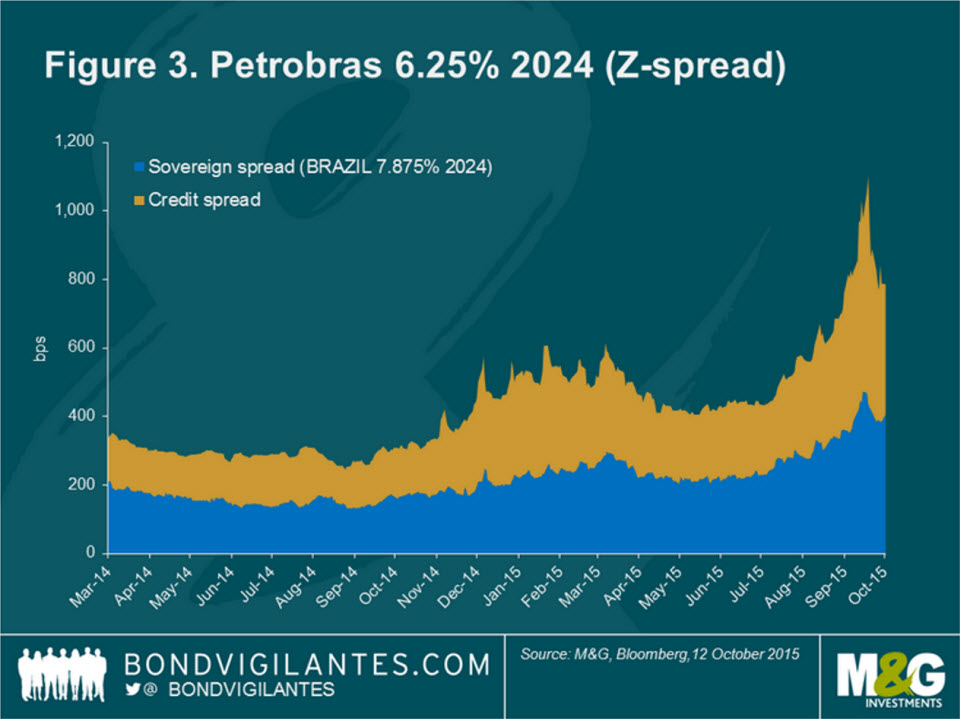

One widely used measure of valuation of quasi-sovereign risk is the spreads offered by hard-currency bonds to its sovereign spreads. With the exception of the Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) bonds, almost all quasi-sovereign bonds trade wider than their corresponding sovereigns since they include an additional layer of risk: corporate credit risk. (Figure 3 provides an example for Petrobras’ bonds yielding 6.25% maturing in 2024). Bank of America Merrill Lynch recently conducted an analysis of quasi-sovereign spreads on 20 of the largest issuers in the Eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa region (EEMEA) and Latin America, all at least 50% owned by their respective government. Interestingly, the study concludes that sovereign spreads account for an average of 55-60% of the total spread – hence, investors bear an average of 40-45% of credit risk on quasi-sovereign bonds. In theory, the weaker the standalone credit profile the higher the credit proportion of spreads, as it is the case for Petrobras, whose credit spreads account for more than 50% of the bonds’ overall spreads.

Emerging market headwinds have resurfaced

The deterioration of emerging market fundamentals has been an important theme in the past 18 months.

On the macro side, all key countries in key regions have shown a weaker tone: (i) Brazil for Latin America faces tremendous economic and political challenges, (ii) Russia for EM Europe is still subject to economic sanctions from the West due to its involvement in the Ukraine crisis, and (iii) China for Asia, which is trying to regain competitiveness by ways of devaluating the renminbi. In addition, low commodity prices have been affecting – albeit unevenly – a number of developing countries and the fear of the adverse impact of the long-awaited US interest rate rise on emerging market debt is also not helping to improve sentiment. On a positive note, the lower oil price context has been a welcome push to most net-importer Asian countries, while Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico are benefiting from a stronger US economy.

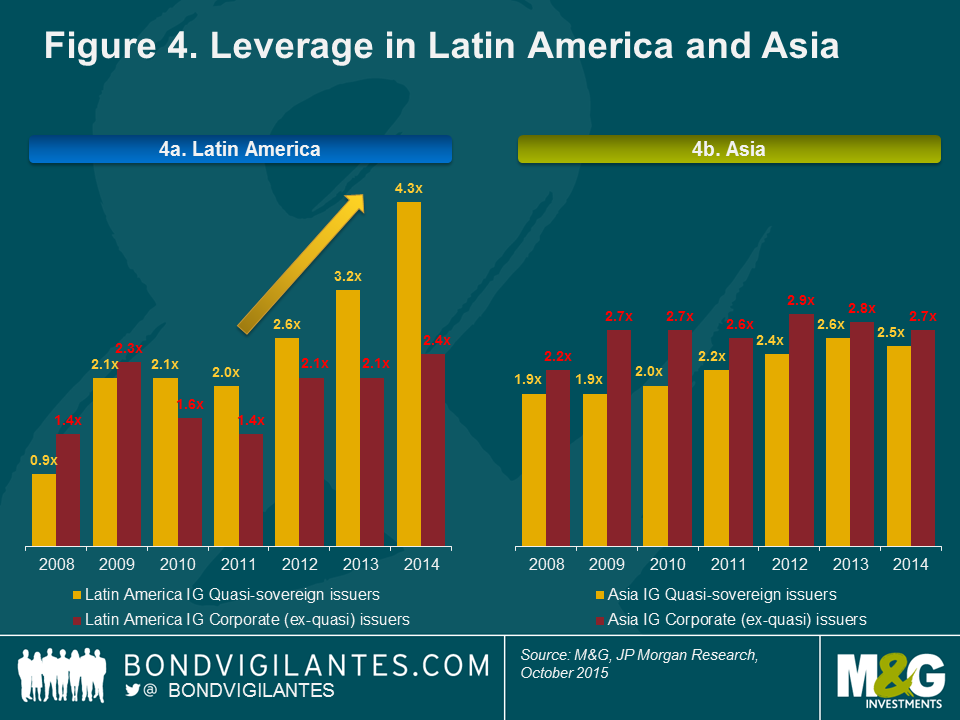

As often is the case in emerging markets, the trends of corporate fundamentals have hardly distinguished from the macro context and the overall picture is also on the downside. The very nature of quasi-sovereign issuers – being a mix of sovereign and corporate – has amplified the impact of the weakening macro backdrop on their fundamentals. For instance, weaker EM currencies in Latin America have had a significant effect on debt metrics for companies indebted in US dollar and with earnings in local currency – as can be seen in the rising leverage of Latin American investment grade (IG) quasi-sovereign issuers (see figures 4a and 4b). On the contrary, it is fair to say that Asian quasi-sovereign issuers have been very resilient despite the strong growth in quasi-bond issuance.

The adjustment on quasi-sovereign bond spreads should continue

Fundamentals have deteriorated in emerging markets, but bond spreads have also become more attractive in the asset class. Investors may, therefore, be considering whether some value has emerged. Our view is that this has not yet happened, based on the following considerations:

– Looking at spreads over sovereign, Asian quasi-sovereign bonds currently look the least attractive. While corporate fundamentals have been resilient across the region, spreads to sovereign have surprisingly not reacted to the deteriorating macroeconomic environment in Asia and averaged 98 bps as of 7 October 2015. It shows that Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are still seen as a safe haven for many investors on the assumption that China would not let a government-owned entity go bankrupt. Given China’s slowing economy and the lack of historical evidence of government bailout in case of default, a cautious approach to Chinese quasi-sovereign credit – with a thorough analysis of the standalone credit profile of issuers – seems essential nevertheless, in our opinion.

– In the EEMEA region, the spread pick-up offered by quasi-sovereigns over their respective sovereign looked attractive at the beginning of the year. However, the easing of geopolitics in Ukraine in the first half of 2015 has led to a strong outperformance and spread tightening of Russian quasi-sovereigns (and corporates) during the period.

– Finally, Latin American quasi sovereign spreads look unsurprisingly wide (average 286 bps as of 7 October 2015, well above historical levels, as shown in figure 5). But this is mainly the result of Brazil and, in particular, Petrobras. Adjusted for the largest country in Latin America, quasi-sovereigns spreads over sovereign excluding Brazil are actually relatively flat (only 25 bps wider) since May 2014. Arguably, they are offering little value as (a) Latin American sovereign bonds have widened by more on the back of the deteriorating macro environments, and (b) standalone credit profiles of quasi-sovereign issuers weakened significantly in the past 18 months.

Despite such factors, the pick-up in spreads of quasi-sovereign bonds above their respective sovereigns should continue to offer opportunities for investors looking for attractive yields, but who are also mindful of the rising default environment in the pure EM corporate bond space. Quasi-sovereigns, relative to pure EM corporates, offer a higher likelihood of government support due to their ownership and general strategic importance for their home countries. A selective approach is key against this backdrop, with careful sovereign and corporate credit research, while investors may also want to consider hedging strategies – such as buying credit default swap (CDS) protection in the respective country – in order to reduce sovereign risk.

US companies issued a record amount of more than €27 billion of euro-denominated bonds (known as ‘reverse Yankees’) in the first quarter of 2015, taking advantage of the relatively low financing costs on offer in Europe compared to their home market. This is just one example of how corporate issuers routinely capitalise on local corporate bond market supply and demand dynamics in search of cheaper finance. Such opportunities are not only available to issuers. Those investors with a sufficiently flexible investment strategy can also exploit relative value opportunities across global corporate bond markets and, in so doing, potentially earn a significant pick-up over more constrained strategies. They can also benefit from the many other advantages that flexible global investing offers, such as diversification.

US dollar credit spreads have widened significantly in relative terms

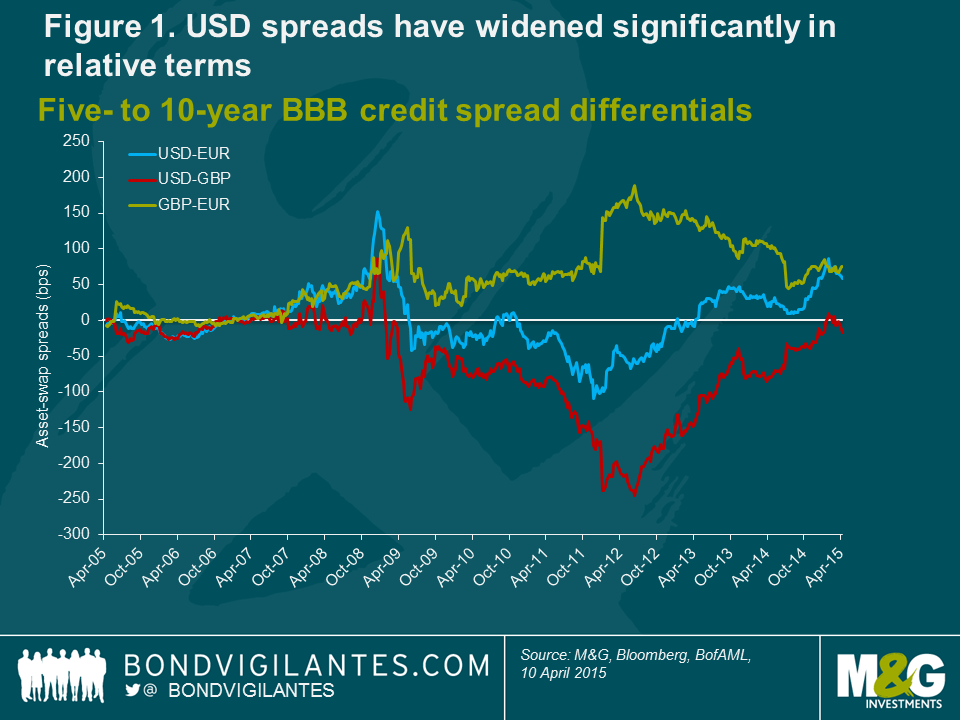

Figure 1 shows changes in credit spread differentials (the differences between credit yields) between USD, EUR and GBP corporate bond markets over the last 10 years, highlighting that USD spreads have widened significantly, in relative terms, more recently. The USD–EUR spread differential has risen by nearly 170 basis points (bps) to +58 bps from -109 bps in November 2011. GBP spreads are currently slightly wider than USD spreads, but the USD–GBP spread has come a long way from its lows of -238 bps at the beginning of 2012 to only -17 bps today. This trend is not confined to USD spreads: relative to EUR spreads, GBP spreads have also outperformed over the past three years, with the GBP–EUR difference trending downwards by around 115 bps since June 2012.

The magnitude of the relative spread movements between USD, EUR and GBP corporate bonds over the past 10 years is also striking. Although we are looking at bonds from the same credit rating band (BBB) and maturity range (5-10 years), the spread differential ranges are substantial. This volatility in spread differentials across corporate bond markets is a powerful argument in favour of global bond investing. At M&G, we look to exploit these cross-market discrepancies through the flexible nature of our fixed income mandates.

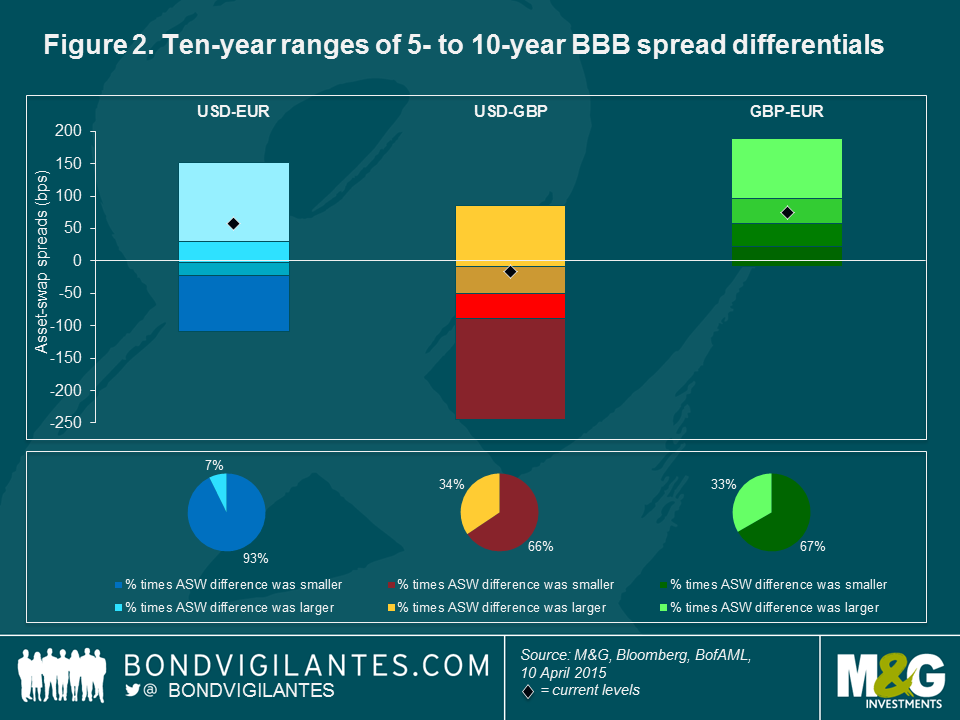

The percentile analysis shown in figure 2 illustrates the spread differential ranges in global corporate bond markets over the past 10 years. The current USD–EUR spread level ranks within the top quartile. Apart from a brief moment at the height of the global financial crisis, USD spreads have never been wider, relative to EUR spreads, in the past 10 years than in the first quarter of 2015. In fact, for about 93% of the time, the differential was smaller (or even negative).

The current values for the other two currency pairs are high relative to their 10-year ranges, too. For roughly two-thirds of the time, the USD–GBP and GBP–EUR differentials have been lower than now, although their position is less extreme than that of the USD–EUR pairing.

On this measure, USD BBB spreads look attractive at the moment, particularly compared to EUR spreads. If we assume that mean reversion (which says that prices and returns eventually move back towards their average over time) will apply, then there is a good chance that USD corporate bonds will outperform EUR bonds on a credit spread basis going forward. But are things really that simple? Unfortunately, they are not.

There are a number of reasons for this. It can be misleading to compare pure credit spread levels between different corporate bond markets without taking the cross-currency basis into account. This is a measure of the premium that borrowers pay to obtain funding in a currency other than their own (see box for more detail). In the case above, this approximate adjustment reduces the attractiveness of USD credit spreads relative to EUR spreads by around 35 bps at the five-year point. Nevertheless, according to our analysis, this leaves an average spread pick-up of approximately 25 bps for switching from EUR into USD BBB credit.

The EUR–USD cross-currency basis

It is surprisingly tricky to compare credit spreads in different currencies on a like-for-like basis. The easiest way to do so is perhaps to think it through from a bond issuer’s perspective. Imagine a US company (A) wants to take advantage of low interest rates in Europe and thus plans to raise debt capital by issuing a EUR-denominated ‘reverse Yankee’ bond. Without any hedges in place, the success (or failure) of this strategy will depend mainly on the future course of interest rates in both markets and the EUR–USD exchange rate. If the company does not have a view on these factors, it will probably decide to hedge away the risks by entering into a cross-currency swap with a counterparty.

The swap works as follows: Company A raises a certain principal amount of EUR debt capital in the European corporate bond market and then passes it on to the counterparty in exchange for the corresponding principal amount in USD, based on the spot EUR–USD exchange rate. During the life of the swap, Company A will pay USD interest on the USD principal to the counterparty, for example, at 3-month USD Libor. In exchange, Company A will receive EUR interest on the EUR principal, for instance at 3-month Euribor plus a certain margin, which can be positive or negative and is called the cross-currency basis. Company A can use these intermediate EUR cashflows to pay the coupons to its EUR bondholders. At the maturity of the swap contract, the USD and EUR principals are again exchanged between Company A and the counterparty. Company A can then use the terminal EUR cashflow to redeem the outstanding EUR bond.

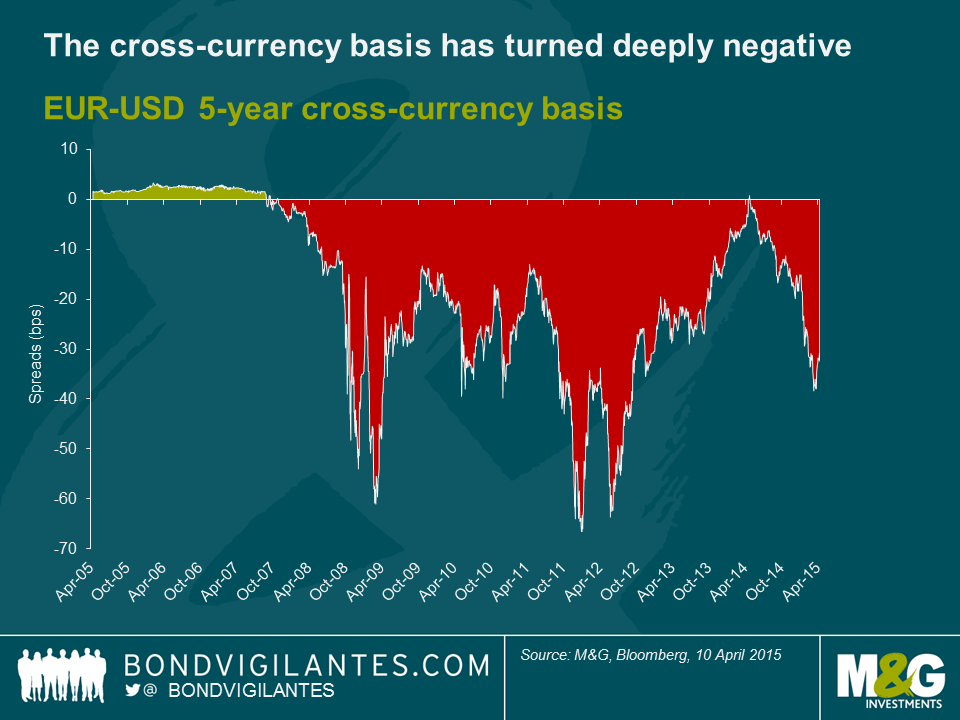

The cross-currency basis moderates market supply and demand for one currency over another. For example, when many US issuers want to issue euro-denominated bonds, as we have seen in the past year, the terms get worse. In other words, the cross-currency basis their counterparties are willing to pay them will decline. As the chart below shows, this is exactly what has been happening: the EUR–USD 5-year cross-currency basis has moved deeply into negative territory to around -35 bps.

The fall of the EUR–USD cross-currency basis thus makes it less appealing for issuers to raise funds in EUR than in USD. Since bond issuers and bond investors are two sides of the same coin, this means that a negative cross-currency basis improves the relative attractiveness of EUR bonds over USD bonds. To put it the other way round, we have to adjust USD–EUR credit spread differentials downwards by essentially adding the negative cross-currency basis to USD spreads.

While this is a simplification, as it ignores other factors affecting credit spread differentials between comparable bonds issued in different currencies, such as home bias, it provides a general indication. The key message is: USD credit spreads are attractive versus EUR spreads for bond investors at the moment, but the valuation difference is less appealing than it looks at first glance.

US credit spreads facing headwinds

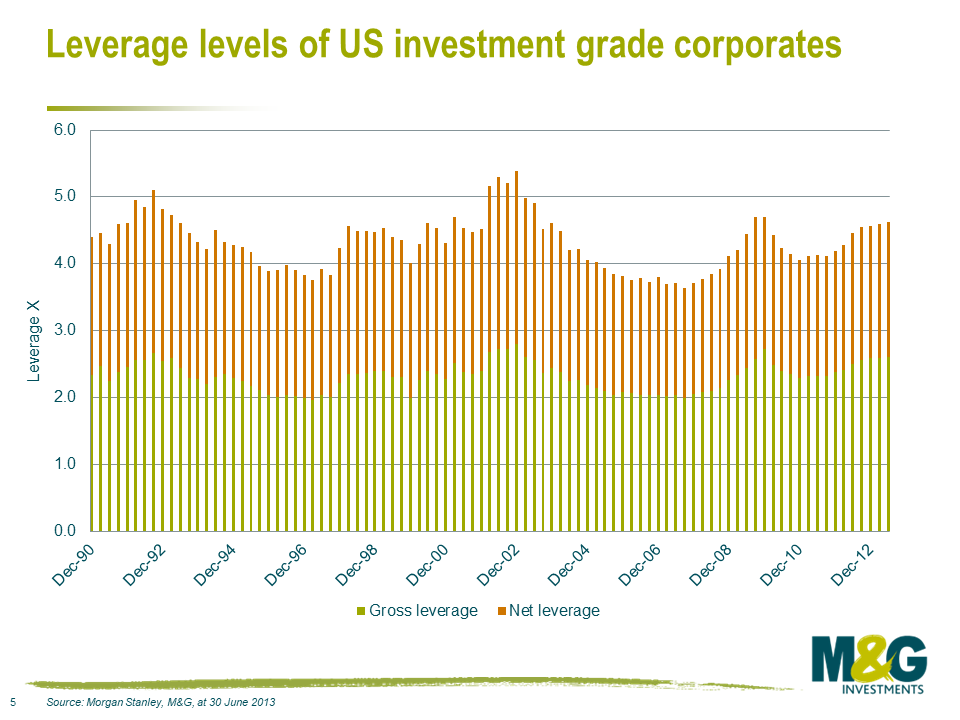

Additionally, even if USD corporate bonds are offering attractive spreads compared to EUR bonds, there may be good reasons for this seeming discrepancy. USD credit spreads are currently facing a number of headwinds, the result of the US economy being at a later stage of the credit cycle than that of Europe. Firstly, leverage has been ticking up and merger and acquisition (M&A) event risk has been rising, at least in certain sectors, notably telecommunications, healthcare and consumer goods. Secondly, export-driven US companies have been hurt by the strengthening of the US dollar against most major currencies. Thirdly, unlike the European Central Bank, which is in fully fledged quantitative easing mode, the Federal Reserve is now providing less monetary stimulus and is likely to hike interest rates in the relatively near future, making refinancing activity for US companies more costly going forward. Fourthly, the energy sector has a much higher weight in USD BBB indices than in EUR indices, and thus average USD credit spreads have been suffering more severely from suppressed oil prices. And finally, many US companies have also been distinctly shareholder-friendly, engaging, for instance, in debt-financed share buy-backs.

All of these points are valid and need to be considered on a case-by-case basis when comparing the relative attractiveness of USD and EUR credit. Yankee bonds, as US dollar-denominated bonds issued by European or other non-US entities are known, offer a way of getting around most of the credit-negative aspects of the US bond market while still getting exposure to the favourable USD credit spreads. In addition, Yankee issuers are often less well researched by US analysts, and thus frequently offer a spread premium to engage the interest of US investors. Similarly, we can often find compelling relative value opportunities in the USD bonds of many US-based issuers at the moment. But within these categories, which maturity band currently presents the most interesting opportunities for corporate bond investors?

Today: record term premiums on offer in USD credit

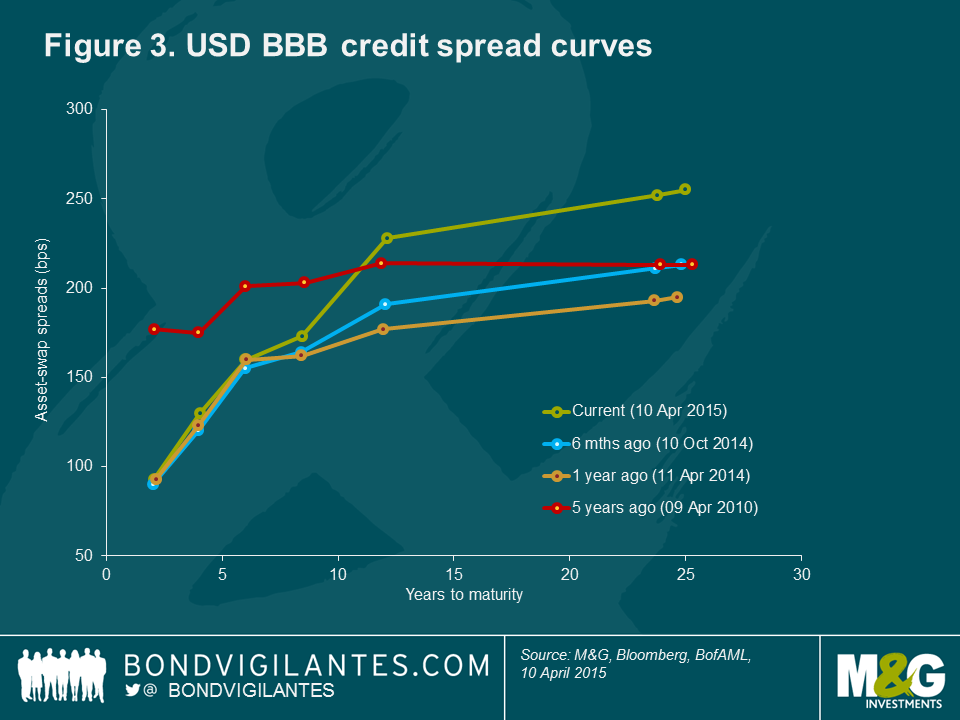

To answer this, we need to look at the steepness of credit spread curves. In figure 3, we have plotted the latest USD BBB credit spread curve alongside historic curves. Over the course of the last year, a considerable steepening has taken place. Interestingly, spreads remained pretty much unchanged at the lower maturity end, but have widened substantially beyond the six-year mark. The 25-year to 6-year spread differential has increased by 60 bps to 95 bps since April 2014. The current 25yr–2yr term premium amounts to 162 bps – about four-and-a-half times that of five years ago.

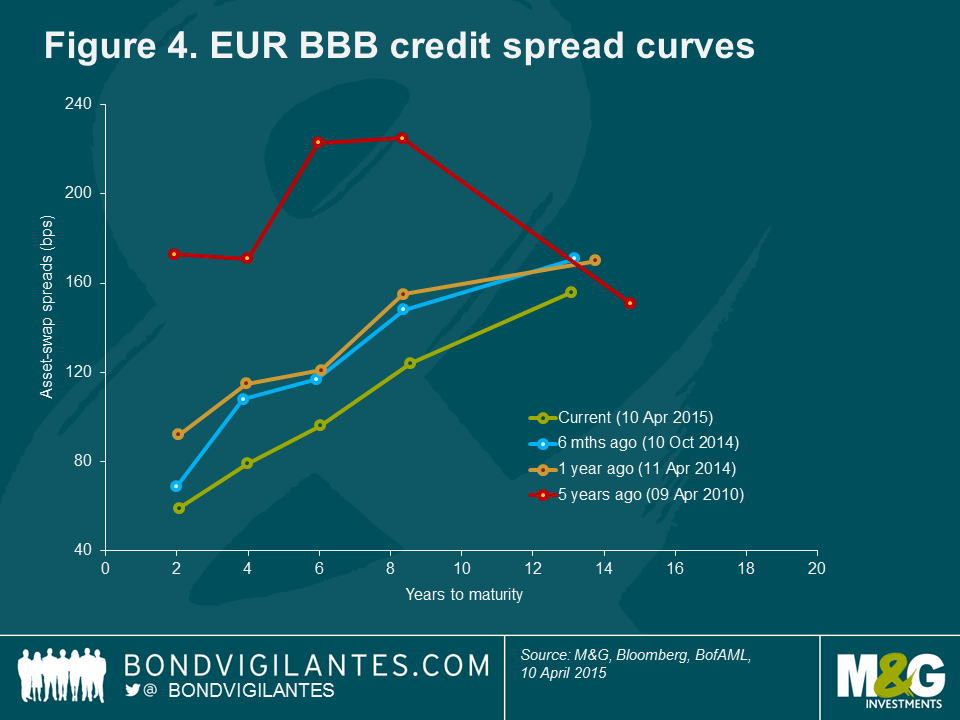

Things are a little different for EUR BBB credit, as shown in figure 4. Lower average maturities in the EUR corporate bond markets result in shortened credit curves. Over the past year, term premiums have moderately increased to 97 bps (13yr–2yr) and 60 bps (13yr–6yr). In contrast to the USD curve, however, the steepening of the EUR credit curve has not resulted from underperformance at the long end. Instead, the whole curve has shifted downwards and spreads at the short end have slightly outperformed those at the long end. In the vast majority of cases, credit spread curves are upward-sloping, which makes sense intuitively, as bond investors typically demand a higher credit risk term premium for lending for a longer time. In times of financial distress, though, credit curves can adopt less regular shapes. The EUR BBB curve from April 2010, for instance, as the eurozone debt crisis gained momentum, displays a significant hump at intermediate maturities.

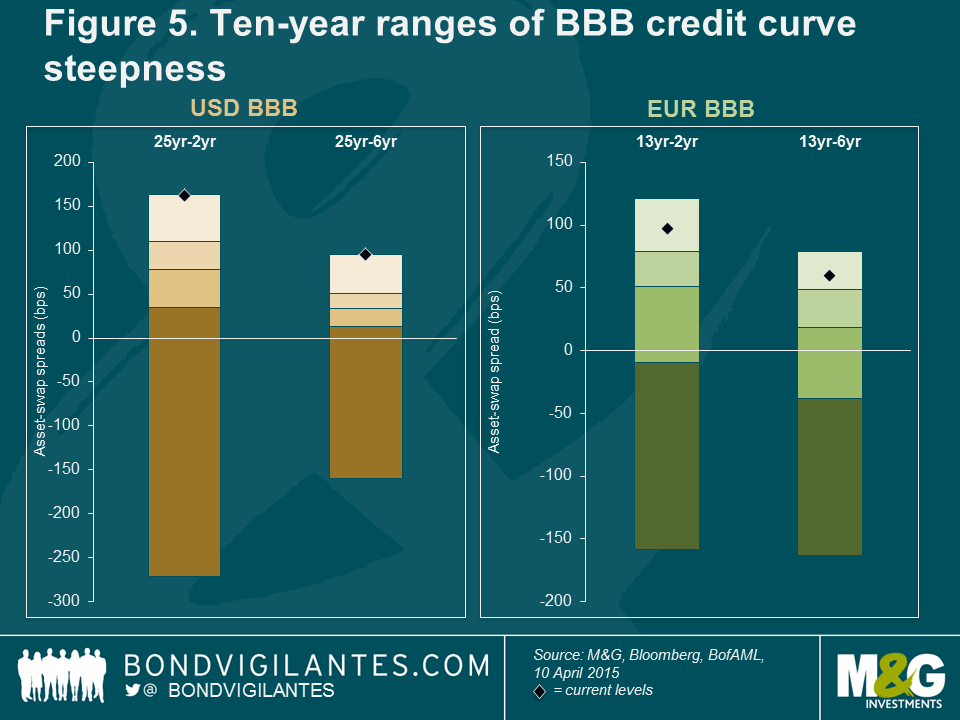

A comparison of the most recent USD and EUR steepness readings versus their 10-year ranges highlights just how steep credit curves are at the moment. All current term premiums shown in figure 5 are located within the top quartile. The situation in the USD BBB bond market is particularly extreme as both the 25yr–2yr and the 25yr–6yr differentials are at record highs, opening up an attractive relative value opportunity. Investors who are willing to take long-dated credit risk exposure in the USD corporate bond market are handsomely compensated in terms of credit spread.

It is worth remembering that a large portion of the steepening in the USD credit curve has been counteracted by the simultaneous flattening of the US Treasury curve, making the total yield pick-up at the long end less compelling. However, for those investors able to lock in pure credit risk exposure, for instance by using US Treasury futures to remove or reduce their duration exposure (their sensitivity to a change in interest rates), long-dated USD credit looks highly appealing at the moment.

Tomorrow: where will the most attractive opportunities lie?

There is little argument that USD corporate bonds are currently attractively valued on a credit spread basis, particularly when compared with their euro-denominated counterparts. Even taking unfavourable cross-currency basis adjustments into account, there is a decent spread pick-up to be gained from switching into USD corporate bonds from EUR corporates. The steepness of the USD credit spread curve has become so extreme that ample term premiums can be earned at the long end.

But this currently favourable valuation of long-dated USD credit represents merely a snapshot in time. The ranges across which both credit spread differentials in global corporate bond markets and credit curve term premiums move are remarkably wide. Adopting a sufficiently flexible global corporate bond strategy enables investors to take advantage of the myriad cross-market relative value opportunities that inevitably present themselves one way or another over time.

It may only be June as I write this, but it already feels as if we have crammed a whole year’s worth of events into the first six months of 2015.

The year kicked off at a whirlwind pace, with the long-awaited announcement by the European Central Bank (ECB) that it would finally begin its quantitative easing (QE) programme nearly upstaged by the Swiss National Bank’s surprise move shortly beforehand to abandon its currency peg. The resulting move in the Swiss franc, the biggest ever one day move in a major currency, combined with the promise of the larger-than-expected €1.2 trillion ECB package helped push significant parts of the bund market into negative yield territory. In Switzerland, 60% of banknotes in circulation are held in the largest CHF1,000 note, perhaps for ease of storage outside of the banking system – a fact that has presented us with an alternative vision for M&G’s staff canteen: one crammed full of heavy metallic safety deposit boxes rather than Styrofoam lunch containers.

This was not all for January: by month-end, a Greek election and the latest in the country’s endless eurozone in/out soap opera, and a grand total of 14 central bank rate cuts had also been squeezed in.

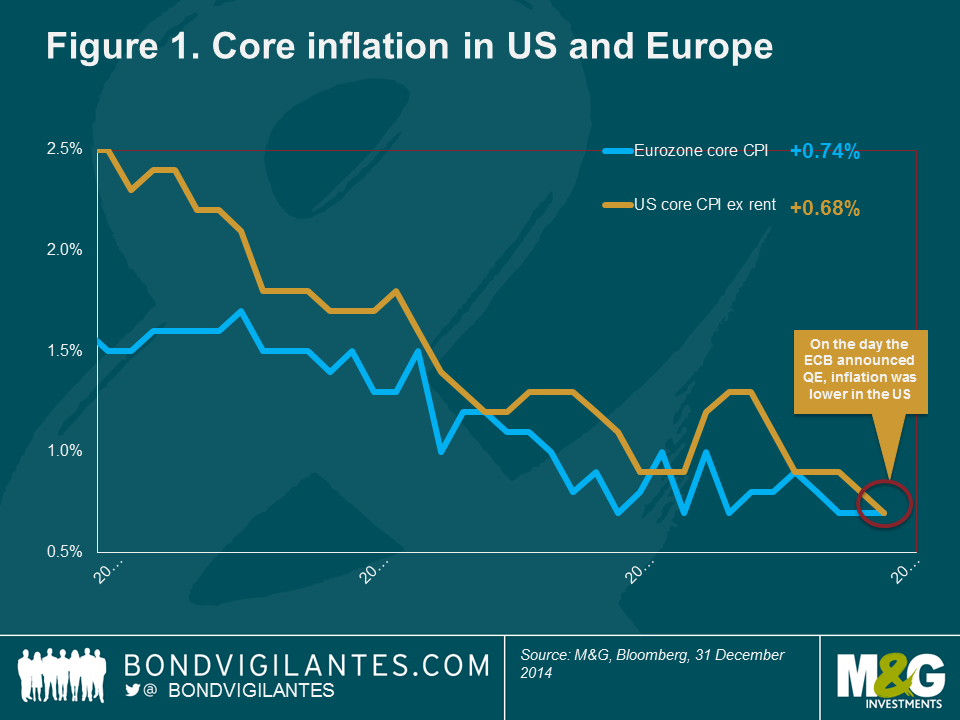

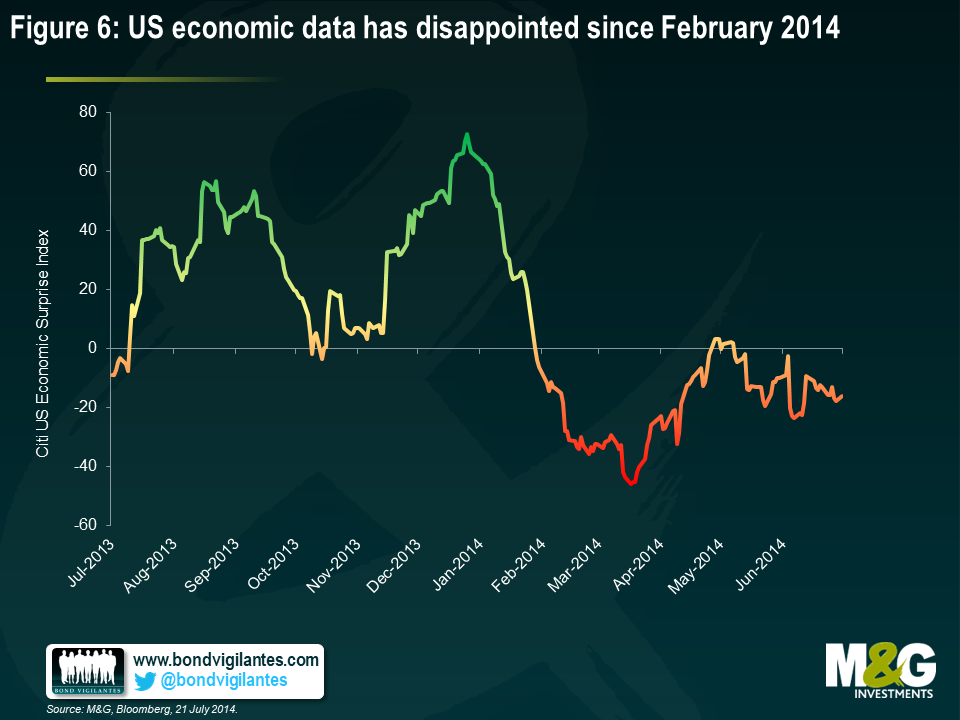

But while markets panicked – and continue to do so – about eurozone deflation, some context can prove illuminating. In this case, as figure 1 shows, on the same January day that the ECB announced its huge balance sheet expansion, US core inflation (on a like-for-like, ex housing basis) was actually lower than in the eurozone and had fallen more quickly. Even so, at that stage, markets still expected a US rate hike in June.

More recently, a government bond sell-off that saw the ‘risk-free’ German 2.5% 2046 bond fall nearly 20% in less than three weeks following a peak on 20 April, has again highlighted the risk to capital that bond investors can face when yield curves rapidly re-price. This has refocused attention on the disparate behaviour of the various fixed income asset classes in such an environment, as well as the importance of duration positioning on bond returns.

The Fed: timing is everything

The Fed (US Federal Reserve) is facing a quandary. After more than six years of close to zero interest rates, it would dearly love to begin hiking, giving it the luxury of having both a brake as well as an accelerator when setting policy. A number of developments over recent months – namely the rally in equities, the growth in the sub-prime auto loans market, and the return more generally of structured credit – worryingly resemble the period 2003-07, during which the Fed kept rates too low. There have also been some early signs of wage growth creeping back into the system, as evidenced by wage hikes for Walmart and McDonalds employees, amongst others. Latest data show US wage inflation running at 2.6% for the first quarter of 2015, up from 1.8% a year earlier.

Central to Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s dashboard of key economic indicators are several employment metrics, including JOLTS (Job Openings and Labour Turnover Survey) and quits (when employees voluntarily leave their current employment, often because they are accepting a new position). These add an extra layer of dynamism to the wider labour market picture. Based on the bullishness of these indicators, a rate hike should soon become a reality. But Yellen and the Fed remember the lessons of the Great Depression well – remove stimulus too soon, and a rapid descent back into recession could be on the cards. The Fed is left gambling that it will be easier to fight inflation by hiking rates than combating deflation in an already zero-bound world. This in turn helps push back the potential risk that higher rates lead to dollar strength, further impacting US corporate profits.

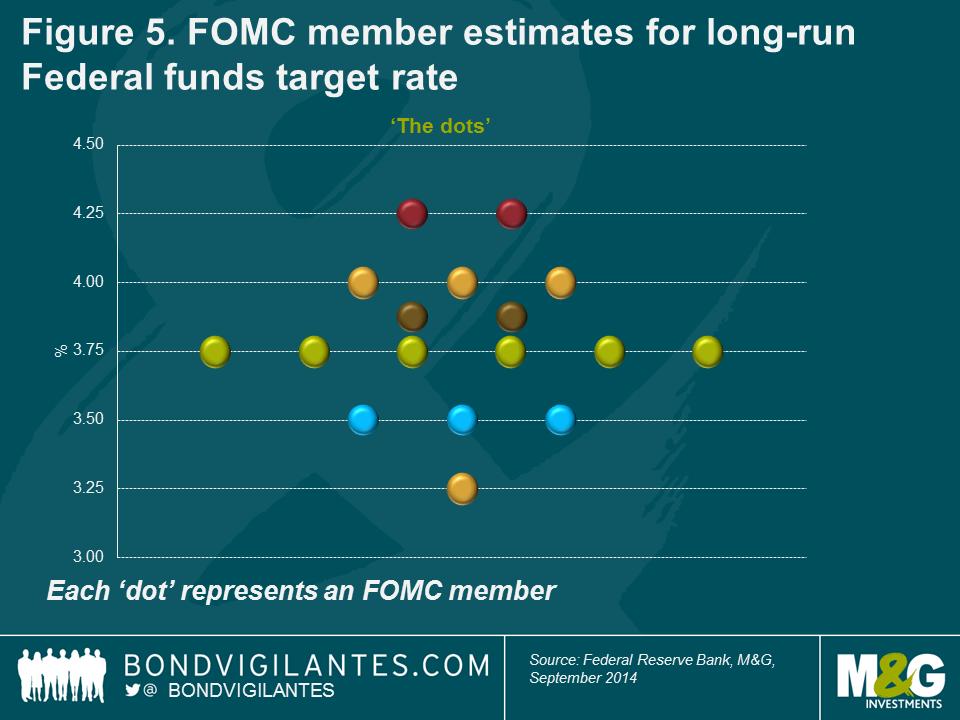

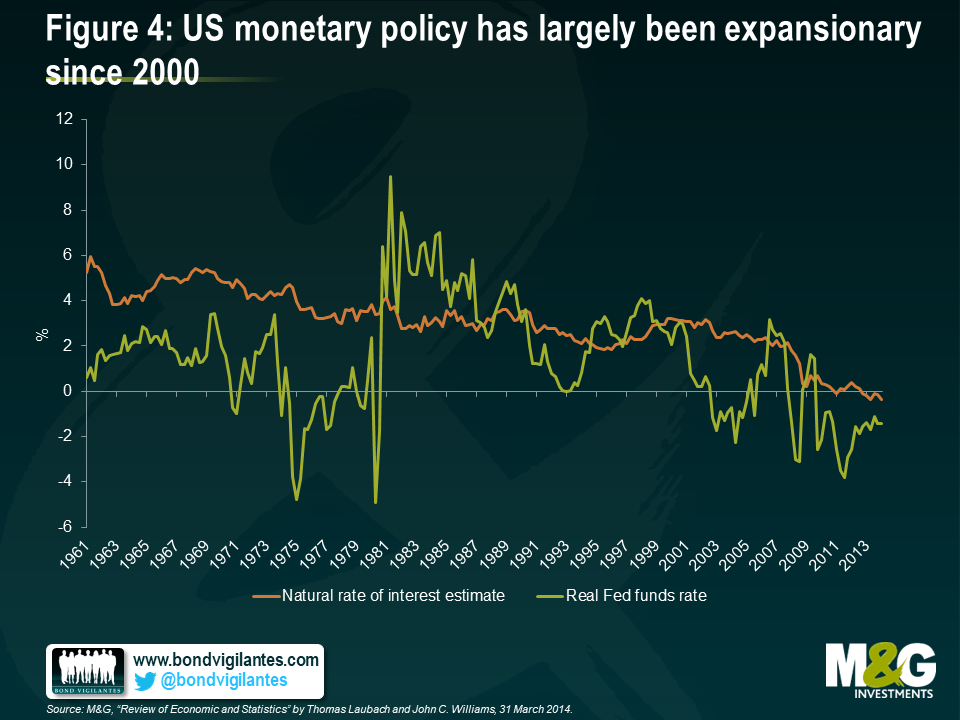

There has been a significant shift in the Fed’s dots charts since the start of the year (as a reminder, Federal Open Market Committee member estimates regarding the long-run Federal Reserve Funds Target Rate as shown in its so-called ‘dots’ chart are helpful when drilling down into how tightening might unfold). The chart provides a guide not only to the direction in which bond yields should go, but also by how much. This shift has brought the Fed’s expectations more into line with what the market is now pricing in (see figure 2). In its current incarnation, it shows the magnitude of term premium (see box on what drives the term premium) and highlights why we remain short duration across our fund range. But this can’t be taken in isolation: the ECB’s liquidity glut is being exported around the world. For a German insurance company needing to deliver guaranteed returns to its customers of, say, 1.5%, it’s a no-brainer to buy 10-year US Treasuries yielding 2% rather than bunds at 0.2%.

What drives the term premium?

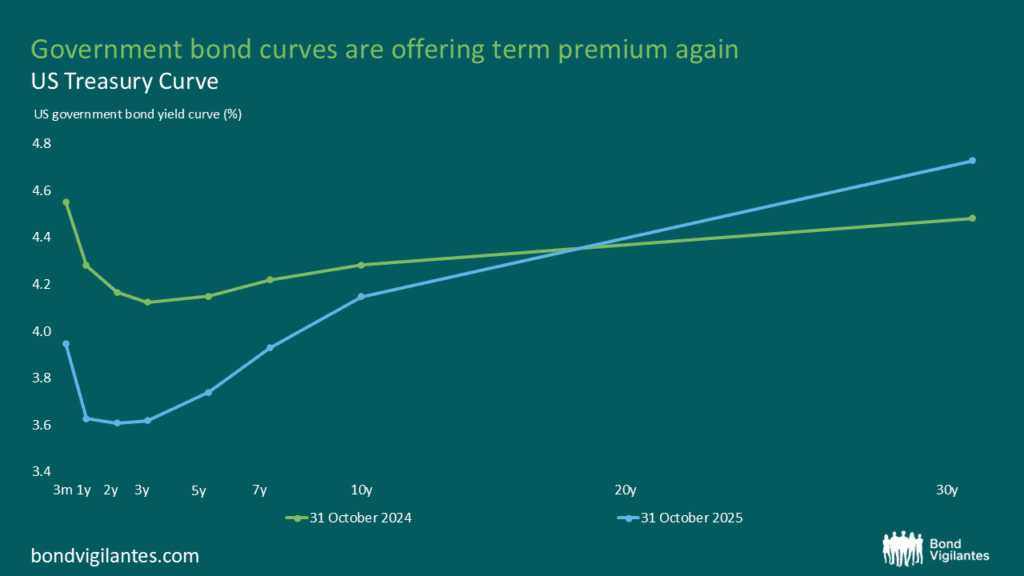

Long-dated government bond yields can be split into three components – expected inflation, expectations about the future path of real short-term interest rates, and a term premium, reflecting the extra return that investors require to own a long-dated bond. Typically, term premium is positive, as investors usually need extra yield to compensate them for the risk of owning longer-dated paper. However, term premium on US Treasuries collapsed last year and recent measures show it to have actually been negative in early 2015.

So what drives the term premium? Historically, the most important factor has been inflation – and the perceived risk of unexpected inflation. A low term premium today suggests that investors currently see little risk of this occurring. Demand and supply factors also exert some influence. For example, US Treasury issuance heavily skewed towards the short end of the curve in the early 2000s contributed to a fall in the term premium around this time.

One possible explanation for the collapse in US term premium in recent months comes from overseas. A higher term premium in the US has historically encouraged portfolio flows into US Treasuries from abroad, and vice versa (see chart). More recently, the diverging policy actions of the Fed and the ECB have had a major impact, with a strong European bond rally in 2014 on expectations of QE from the ECB.

The implication here is that longer-dated US bond yields have, at least recently, had little to do with US-specific factors. The impact of the belated arrival of the ECB’s QE is now being exported to the US. This suggests that the Fed is far from being in complete control of its own monetary policy and gives Fed Chair Janet Yellen yet another issue to consider in her deliberations on exactly when, and how aggressively, to finally begin hiking US interest rates.

Europe: better prospects on the horizon

Turning to Europe, it’s fair to say that if you were designing policies to generate deflation, you would have followed the exact path followed by the region’s policymakers in recent years. Europe has adopted the polar opposite of the three arrows espoused under ‘Abenomics’ (in Japan). From a monetary perspective, policy decisions had drained some 40% from the eurozone’s balance sheet by the end of 2013, although more recent decisions have reduced this somewhat to a little over 20% (see figure 3). From a fiscal standpoint, excessive austerity and Germany’s focus on ‘Black Zero’ (its goal of moving from a budget deficit to a small surplus for the first time since 1969) mean there is little appetite or ability to fight deflation in this way. Structural reform has been equally slow.

But there is now – finally – some good news, with the introduction of potentially limitless QE, the likelihood of less fiscal austerity to come, and some small signs of structural reform. Regarding the latter, Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi has to date struggled to make much progress with his ambitious reformist agenda, so any advancement here could prove significant.

The potentially even better news is that the ECB’s programme of asset-backed securities (ABS) purchases has not really begun yet. This may take time to pick up speed, but if it does so, it should provide a good way for banks to get stale loans off their balance sheets, by repackaging them and selling on to the ECB at a profit. This should, in turn, support bank profitability, shrink banks’ balance sheets and enable new loans.

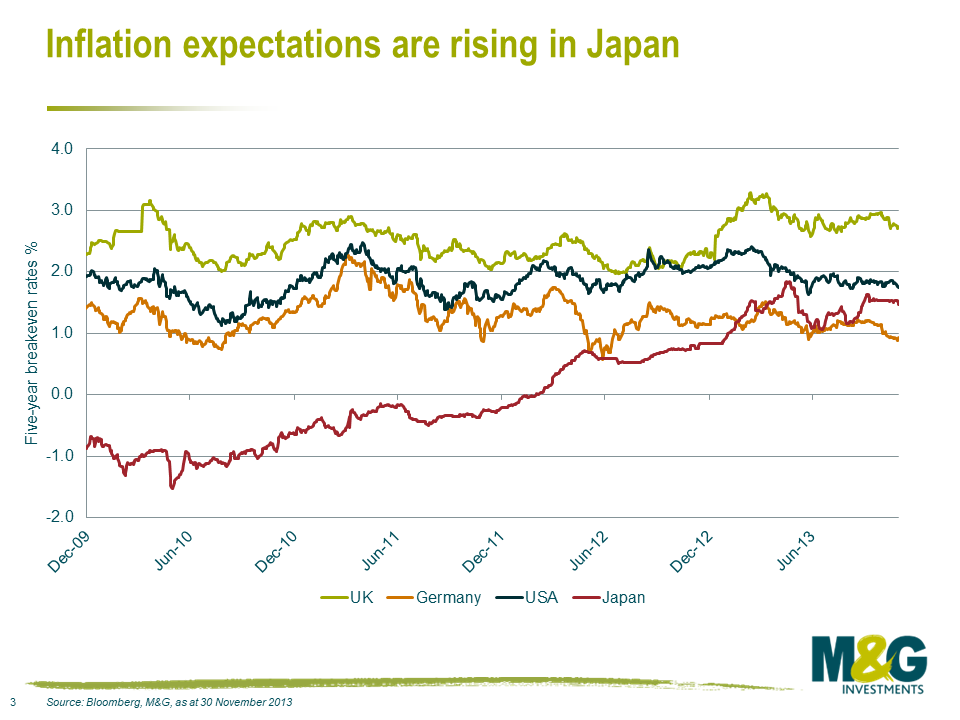

While it is still early days to apportion significant results to the ECB’s QE programme, the eurozone officially moved out of deflationary territory in April, following four months of falling prices. This modestly higher inflation figure, along with a recovery in oil prices, a weaker single currency, and improvement in economic data has created a renewed demand for inflation-linked assets. In our view, despite a strong rally in recent months, European breakeven rates continue to price in too little inflation over the medium term, and so short-dated government linkers offer good value versus conventional government bonds.

Credit: technical, valuations and fundamentals suggest value

QE changes investors’ behaviour, leading them further out along the risk curve against suppressed government bond yields. In recent months, we have begun to find better relative value on a selective basis in the high yield market following the underperformance by segments of the asset class in the latter part of 2014. Importantly, going forward, the ECB and Bank of Japan QE packages should support demand for high yield bonds.

I wrote at the end of last year about my preference for the floating-rate note (FRN) segment of the market. This remains a valid means of taking advantage of further US dollar strength, Fed rate hikes and improving US corporate and banking sector health. I have also been finding value in conventional US corporate bonds. US spreads actually widened in 2014, partly due to huge new issuance and the knock-on effects for energy companies of the oil price collapse later in the year. Investment-grade corporate bonds look attractive at the moment, according to the three key factors of technical, valuations and fundamentals. Meanwhile, liquidity has again been a hot topic in the press in recent months, and is something that investors are right to be mindful of in the present environment (see box on liquidity).

Liquidity: an ever-present challenge

Back at the end of 2014, we wrote about the changing face of corporate bond market liquidity, and how liquidity conditions in today’s world appear increasingly linked to the direction of spreads (decent in times of narrowing spreads, and correspondingly poor as they widen). The topic of liquidity has not gone away since then, and indeed has been exacerbated by the second-quarter government bond market sell-off that has sent bond yields soaring.

A lack of liquidity in and of itself is not necessarily something to be feared, as long as an appropriate level of liquidity management is observed. Liquidity risk is often misunderstood: a bond could be defined as perfectly liquid, should an investor be prepared to sell at a significant discount. Instead, we define liquidity as the ’cost of immediacy of trading’, that is, the ability to execute trades at a reasonable market level.

Like all risks, investors can be rewarded for accepting liquidity risk, charging a premium that can be attractive in today’s low-yield environment. In fact, we see significant value in doing so in certain segments of the markets. In our view, investors in BBB rated corporate bonds are being paid well in excess of the liquidity and default premia that we feel investors can demand for the risks involved in lending to these investment grade-rated companies (see chart).

To mitigate liquidity risk, managers can undertake measures that include (but aren’t limited to) investing in government bonds; holding short duration, high-quality corporate bonds; holding a cash or cash-like buffer; favouring on-the-run (most frequently traded) bonds over off-the-run bonds; owning senior debt relative to subordinated debt; using derivatives like credit default swaps and futures; investing in primary market issuance as a source of supply; and maintaining diversified portfolios with concentration limits.

At M&G, liquidity management is embedded within our investment process. We also have a dedicated risk management team, and a formal governance structure in place that carries specific liquidity management responsibilities.

Emerging markets: sovereigns look safer than corporates

It should be no surprise to hear us describe ourselves as longstanding China bears – a standpoint that seems entirely consistent with the slower growth we have seen coming out of the country.

I have been wary of emerging markets (EM) for some time based on a number of themes, including the strengthening US dollar as well as slowing Chinese growth. But as usual there are two sides to every story. Emerging market sovereigns, having largely borrowed in local currency rather than US dollars, are not in terrible positions and have some control over their own destiny. The picture is somewhat less rosy for EM corporate issuers, who took greater advantage of low US dollar-denominated borrowing costs and, in so doing, have created a bigger market than the US high yield market. Many of these have not hedged their dollar liabilities and will be particularly vulnerable when higher rates do take hold.

As usual, the key is to be selective. For example, I have bought some local currency Mexican and Colombian debt since the start of the year due to the aggressive sell-off in both currencies in 2014.

Currency: further US dollar strength on the cards

The strong US dollar has been a big story during much of 2014 and into the first part of 2015, and we expect dollar strength to continue, based on the relative strength of the US economy and likelihood of more imminent rate rises there than elsewhere.

That said, given the significance of the greenback’s rise versus other key currencies, such as the euro, since the start of the year, I took some profits in the currency during the first quarter as the rise in the dollar had been quite extreme. However, over the last few weeks, I have been adding some dollar exposure back as I expect the US Fed to be the first major central bank to raise interest rates, and interest rate differentials are likely to be a key driver of currencies over the next 12 months.

As the dust settles following the UK election result – in which voters and investors alike were surprised to see the Conservative party achieve a parliamentary majority (albeit a slim one) – recent sterling strength may be challenged. In our view, a dovish Bank of England, the UK’s very large current account deficit, and the renewed prospect of an in/out referendum on British membership of the European Union by 2017 will likely weigh on the currency. As a result, we remain wary (read: underweight) on sterling. While it may feel like 2015 can’t yield too many more surprises, in reality, the second half of the year could yet turn out to be equally frenetic.

It has become customary in recent years for January to begin with strategists making dire predictions for bond markets. And yet 2014 has, like its immediate predecessors, conspired to confound the vast majority of these expectations. While equity markets have delivered decent returns in the main this year, the predicted bond market rout has failed to materialise.

Download the PDF version of the Panoramic Outlook

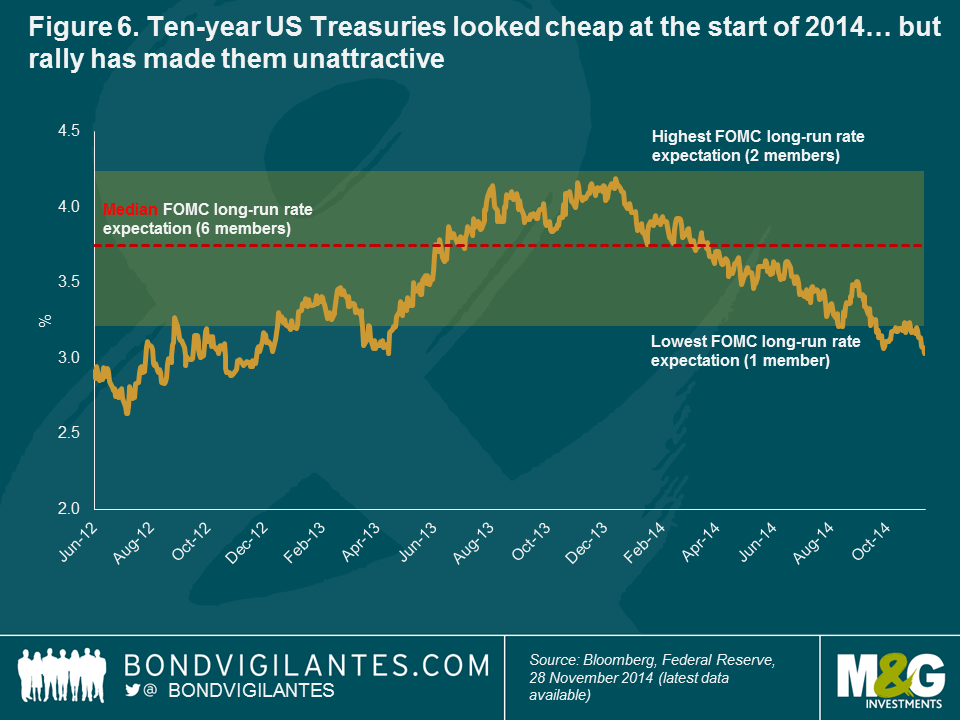

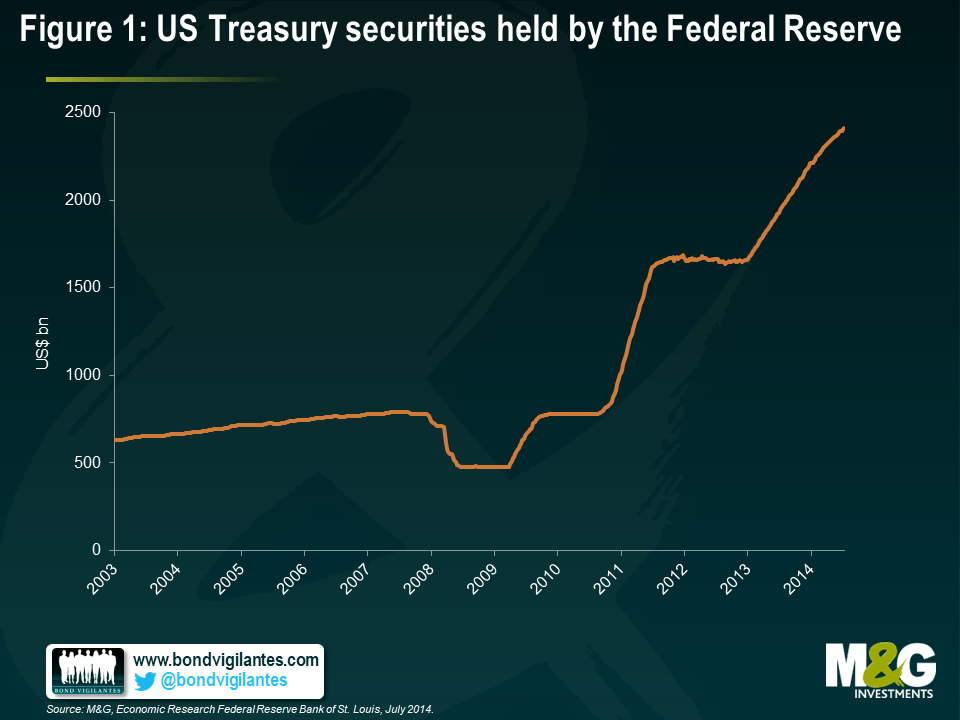

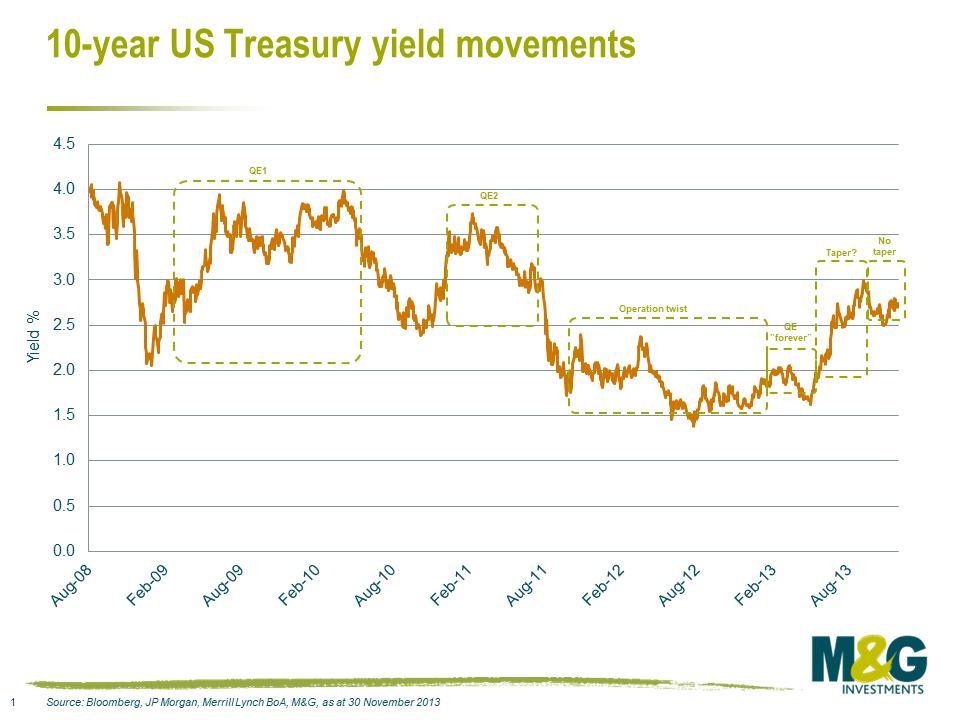

At the start of 2014, the consensus was that 10-year US Treasury yields would rise north of 3.25%. This was based on the view that the US Federal Reserve (Fed) would end its six-year quantitative easing (QE) programme, which has seen its balance sheet swell to more than US$4.5 trillion, and that the country’s growth would start to become self-sustaining.

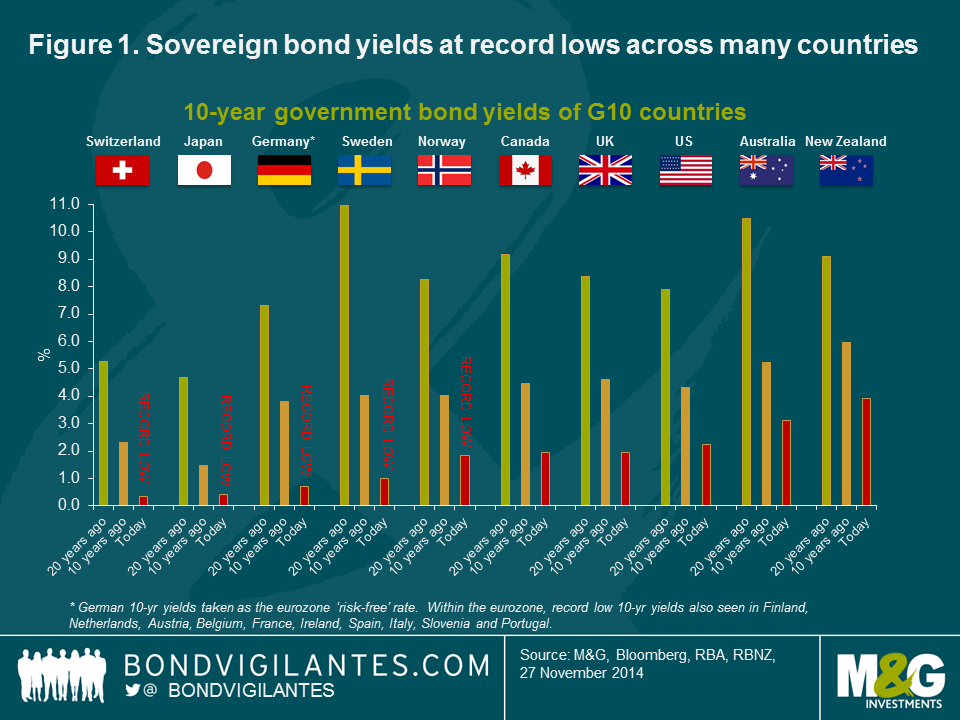

As I write, the US is growing nicely and the Fed did indeed end QE in October. Yet global government bond yields have plummeted – yields on 10-year US Treasuries were 2.2% at the end of November, and European bond yields are at all-time lows (see figure 1). The same is true for Japan. So what explains the further collapse in bond yields that caught almost every Wall Street strategist and economist off guard (with the notable exception of HSBC’s Steven Major, who forecast 10-year Treasuries at 2.1% by year-end), and what does it mean for bond investors in 2015?

Wintry weather, resurgent geopolitics

To start with a summary: 2014 began with some awful weather in the US, leading to a very weak first-quarter gross domestic product (GDP) headline figure. Ben Bernanke then held a series of hedge fund-hosted dinners, just months after standing down as Fed chairman, in which he told those listening that the market’s view of normality was too rosy – rates, yields, growth and inflation would all, in the Fed’s view, be lower than the market was pricing. Waves of geopolitics then hit: Russia/Ukraine, Middle East violence, Hong Kong’s anti-Chinese protests, and Ebola. These ‘risk-off’ events stimulated a flight to quality amongst investors. Safe-haven assets like high-quality government bonds benefited from the uncertainty caused by these geopolitical factors.

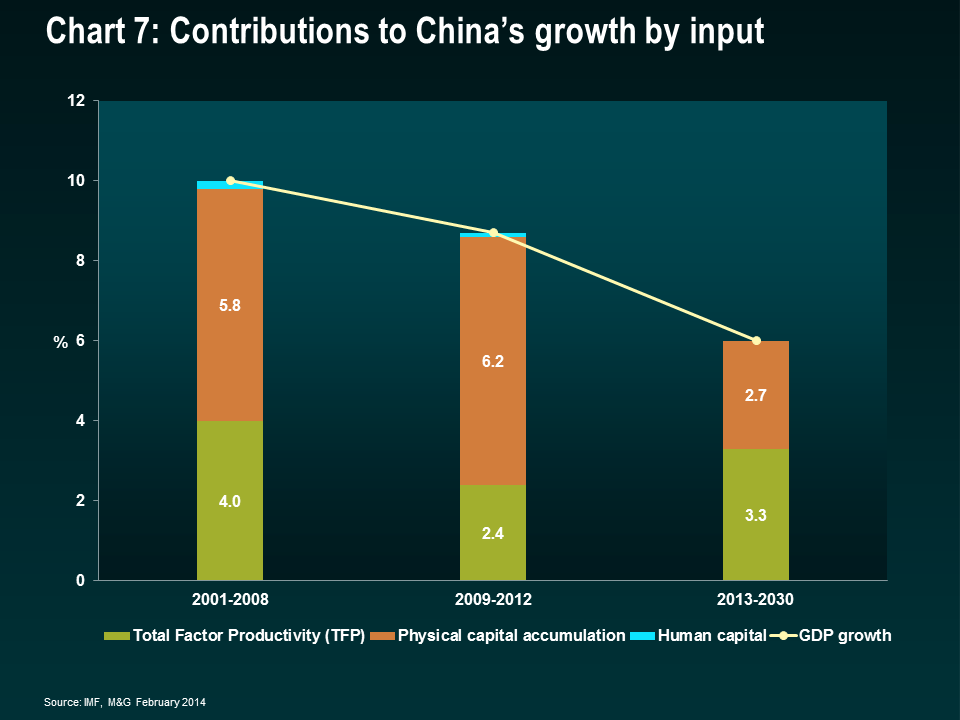

The Real Level of China GDP Growth

Perhaps one of the most frequent questions about China’s record decade of growth is whether it is actually real. Commonly, there are a number of reasons to doubt the accuracy of China’s GDP data. To begin with, the Chinese local government structure has various political disincentives to reporting accurate GDP figures. Local officials are promoted almost entirely on the basis of their locality’s growth rates, hugely motivating them to report increasing GDP figures. At the central government level, it appears politically necessary that GDP continues to rise, particularly now as policymakers are pressured to sustain growth in the face of a rebalancing economy.

One reason for economists’ scepticism over China’s GDP numbers is that the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics takes just two weeks to collect its GDP data, compared with six weeks for (the much smaller) Hong Kong, and eight for the US.Even China’s premier, Li Keqiang, has expressed doubts about the data, admitting, over dinner with the US ambassador to China in 2007, that the figures were, “man-made and therefore an unreliable statistic”. Instead, he suggested focusing on three data points – electricity consumption, rail cargo volume and bank lending – as a better proxy to evaluate China’s economic progress.

Economists have, since then, tried to put together alternative indices to gauge China’s true growth. We recently discussed Citigroup’s inspired ‘Li Keqiang Index’ which uses the three indicators mentioned above. To nobody’s surprise, it points to a more pronounced slump in growth than that suggested by official Chinese numbers.

China’s debt levels built up dramatically over the past decade. Thanks to recent policies aimed at limiting the supply of new credit, debt growth is now slowing. The property market is one of the most sensitive barometers of this, with monthly house price declines in roughly 75% of Chinese cities recently. There is also evidence that the market is saturated and inventories have ballooned. Yet, in spite of this, GDP growth in the third quarter came in better than expected at an annualised rate of 7.3%.

Some argue that the reliability of the ‘Li Keqiang Index’ may be compromised since its underlying indicators were mentioned. Back in 2007, when the conversation took place, the Chinese economy, and the Liaoning province in particular, were far more reliant on heavy industry. However, the structure of the national economy has changed dramatically and today, the services sector accounts for a greater share of the economy, requiring a very different method of measurement.

Given the challenges of assessing the real level of China’s GDP, some of the volume data, such as power and rail freight, may be interesting as there is less incentive at the local government level to massage them. However, they only reveal part of the truth and must be assessed in conjunction with a broader range of economic indicators. Regardless, the various data sources seem to be converging around the point we have been arguing for many years – that China’s growth is slowing and this will ultimately have significant consequences for countries that have become increasingly reliant on strong Chinese growth.

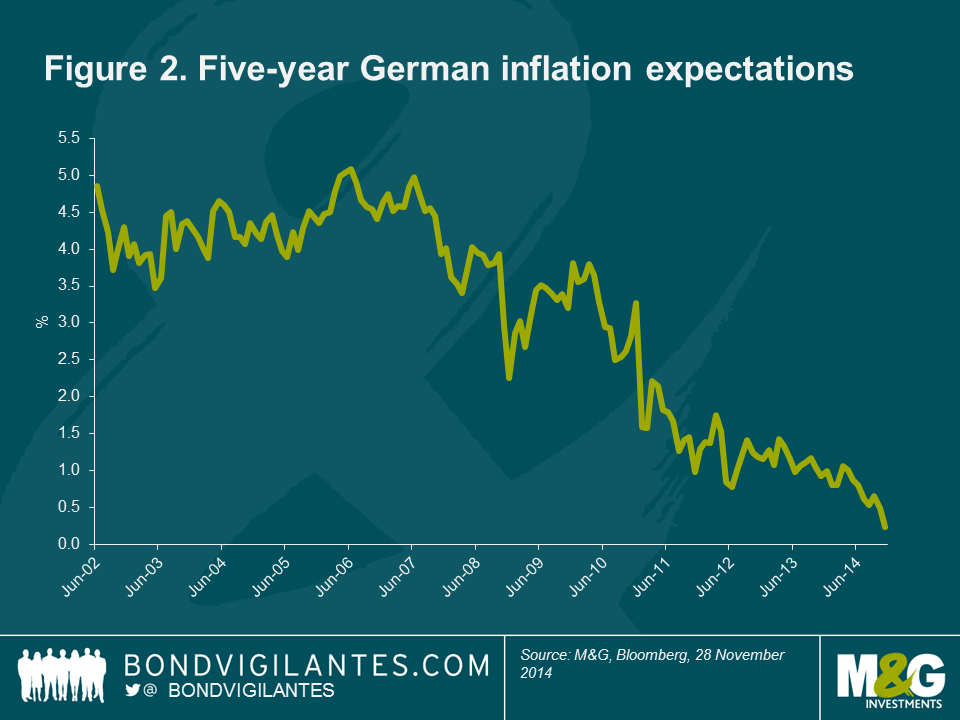

Finally, and perhaps most importantly as we look into 2015, we have a global deflation scare – the new aim for central bankers is to get inflation up to 2%, rather than driving it down as before. Recent Consumer Prices Index (CPI) levels of 1.7% in the US and 1.3% in the UK give moderate cause for concern, but it is the eurozone, with annual inflation of just 0.4%, that is the real worry, particularly as this includes five peripheral eurozone economies that are now in deflation (Greece, Spain, Italy, Slovenia and Slovakia).

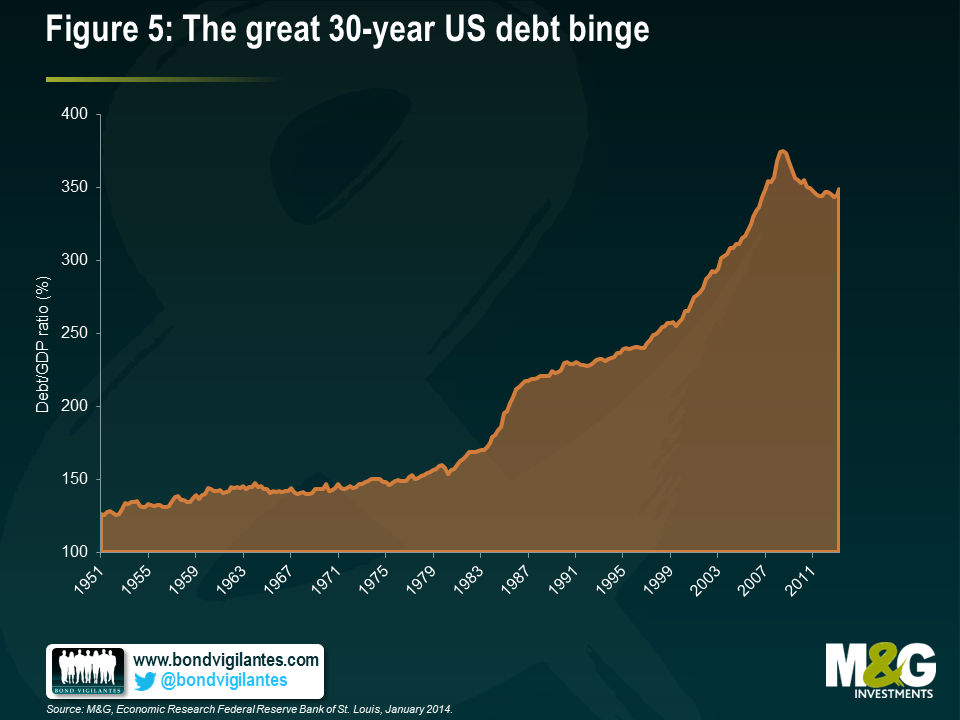

Many are questioning why 2014 did not turn out as they had predicted. Larry Summers, former US Treasury Secretary and economic adviser to Barack Obama, believes that developed economies are entering into a period of ‘secular stagnation’ – an environment in which growth in rich economies grinds to a halt due to significant underinvestment in future potential. If secular stagnation sets in, the only way to fuel growth is through the development of mini asset bubbles which aim to drive consumption levels higher.

Another reason that some investors are pointing to in order to explain the fall in yields this year is a high level of global savings and liquidity after multiple rounds of central bank quantitative easing. Others suggest that yields are low because governments are too reliant on central banks and haven’t done enough to facilitate sustainable economic growth.

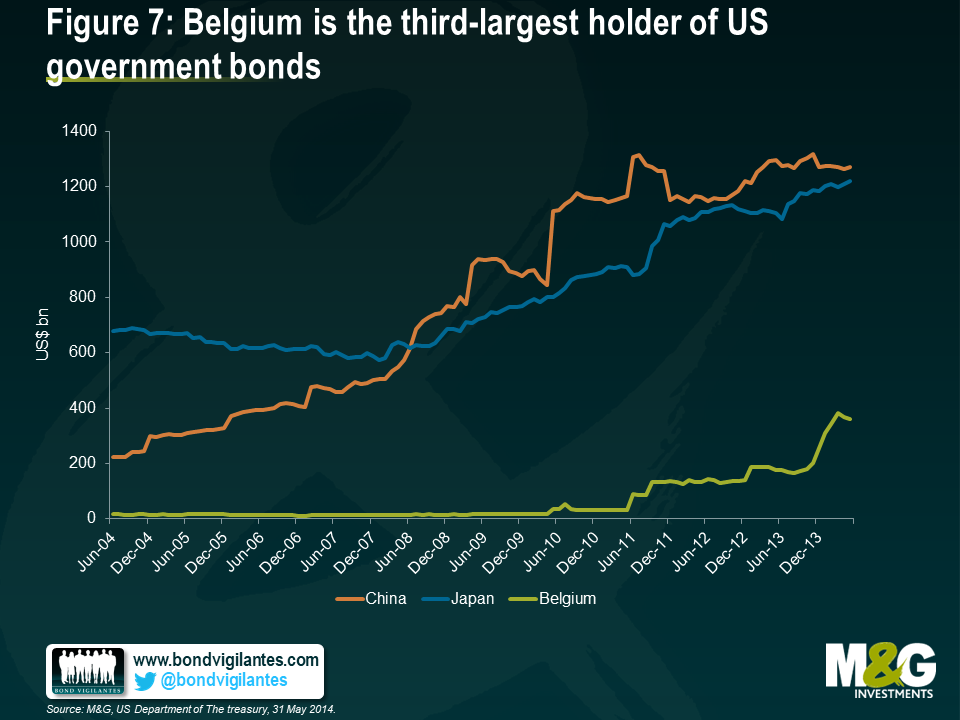

There’s certainly some truth in the idea that if the US government hadn’t fallen over the fiscal cliff in 2013, if the European Commission and the German government had loosened their approach to austerity and deficit reduction, and if the European Central Bank (ECB) had increased rather than shrunk its balance sheet in the past couple of years, we might not be in this position. But these new deflationary pressures aren’t coming purely from the western world. China’s economy is inescapably slowing (see box entitled The real level of China GDP growth). This isn’t necessarily a problem for China itself, as its institutions are very used to micromanaging different parts of its vast economy and regions, and it also owns around US$1.3 trillion of US Treasuries that it could sell to finance a fiscal stimulus if required.

However, the knock-on effects of a China slowdown are significant. Lower growth means less investment in infrastructure, housing and other construction projects. The prices of raw materials could fall – those minerals and metals that are exported by countries such as Chile, South Africa and Australia. Chinese consumers could have less disposable income to buy New Zealand’s premium powdered milk, and firms may spend less on German capital goods or American digger trucks. And it means that the downward pressure on global energy prices is coinciding with a Saudi Arabian oil glut and US energy self-sufficiency on the back of the shale oil revolution.

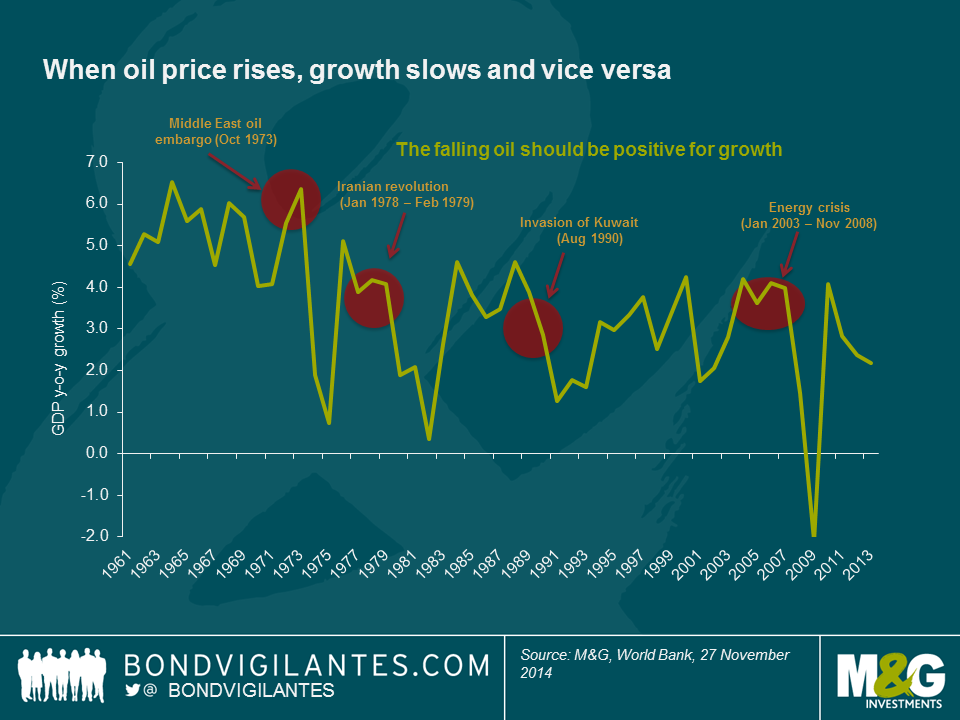

It has been this collapse in oil prices (see box entitled Oil’s positive shock), from US$120+/barrel to less than US$75/barrel, that will have a significant impact on headline inflation numbers, especially in the US where low taxes on gasoline at the pump mean that oil price falls feed through quickly and aggressively into the CPI. In the UK and Europe, where most of the cost of fuel is tax, the impact is more muted but still present.

Deflation: the new enemy

Surely this is good news for consumers? Absolutely! History shows that movements in energy costs are perhaps the single biggest driver of changes in economic growth. As a result, 2015 should be a year where growth rates finally get the help they need to reach escape velocity. It’s the single biggest reason to be cheerful.

But in some ways, central bankers will regard this latest weakness in commodity prices (and, for largely unrelated reasons, food prices) as inconvenient at best. With inflation numbers well below those 2% targets, consumer and market expectations of future inflation deteriorating, and interest rates already at the zero bound, they are flirting with deflation. Indeed, there is a growing nervousness that not only are asset bubbles being created, but that we are nearing a situation of ‘Japanification’, in which both consumption and corporate investment is permanently deferred as individuals and businesses realise that falling prices means there it is never a good idea to buy something today.

The eurozone crisis to date has been characterised by last-minute action, with seemingly great reluctance from Germany. What’s more, that action has been driven by financial markets rather than cold economic data, political pressure from peripheral governments, or even street protests. This time could be slightly different, as for the first time Germany’s economy is also in trouble, as it finds itself unable to find buyers for its exports. But with Germany continuing to put emphasis on ‘Black Zero’, its goal of moving from a budget deficit to a small surplus for the first time since 1969, it looks unlikely that fiscal largesse will play a part in any concerted deflation-fighting policies. So that leaves the ECB, itself part responsible for the current predicament through its shrinking balance sheet.

Oil’s Positive Shock

The path of oil prices has been far from steady over the last few decades. In 1973, the world’s major industrial countries were faced with an oil embargo from the Middle East, leading to a petrol shortage. The ensuing crisis caused economic growth in a number of countries, including the US and UK, to stagnate as oil prices quadrupled. Then in 1979, oil production fell as a consequence of the Iranian Revolution, again causing oil prices to rocket.

The 1990s witnessed the next significant spike in prices, this time in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. More recently, a combination of supply and demand factors contributed to the oil price ascending between 2003 and 2008.

But this time it’s different – oil prices have tumbled and now stand at five-year lows. Historically, significant changes in the oil price have been driven by supply constraints and high demand, resulting in a drag on world GDP. In recent times, however, the oil price has been driven lower by an oil glut. Excess supply from both the US and OPEC has resulted in a flood of oil against a backdrop of flat consumption. Meanwhile, OPEC officials confirmed after their meeting in October that the organisation is in no hurry to cut output.

The current positive supply shock transfers real income from producers to households, which should have an impact on the wider economy through increased spending and demand for other goods. With oil prices falling, the global economy is set to benefit from an estimated US$200 billion uplift. As an input to production, lower oil prices also make it economically feasible to produce more GDP with existing technology. Although deflationary in the short term, this is expected to be positive for world growth over longer time horizons, as the fall in oil price provides great consumer stimulus which (all else being equal) should help to lift global GDP in 2015.

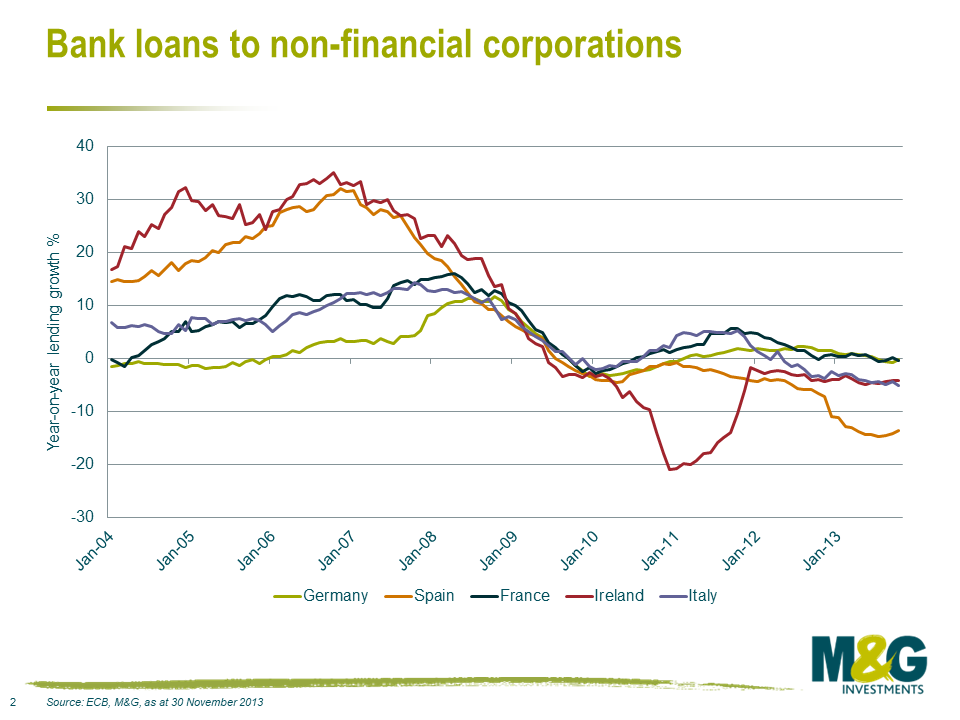

The ECB finally started to buy covered bonds and asset-backed securities during the autumn, and has reintroduced a targeted long-term lending programme (the T-LTRO) in order to stimulate private-sector borrowing. So far, none of these activities has been the ‘big bazooka’ that might change sentiment in the same way as QE was for the Fed, Bank of England, and now even the Bank of Japan.

There are some signs of hope: whilst initial take-up of the T-LTRO facility was disappointing, it’s likely that some of this was related to the announcement of the ECB’s own stress test results. Now that the Asset Quality Review is finished, and banks know whether they passed or failed, there is capital raising to be done. As a result, we expect a large amount of so-called AT1 bank debt to be issued in the coming months (see box entitled The rise and rise of CoCos). It also means that the uncertainty around the stability and capital needs of the eurozone’s banking sector is behind us, and that banks can lend the ECB’s cheap money on to their customers. We expect future demand for T-LTROs to increase, helping to reverse the decline in the ECB’s balance sheet and boosting end demand.

Whilst full-blown quantitative easing has yet to materialise, ECB President Mario Draghi and other council members have made it clear that it continues to be an option. Legal challenges to this from the German Constitutional Court remain a possibility. But if inflation fails to stabilise in the coming months, we expect to see out-and-out QE in 2015, with bond purchases spread across eurozone member nations in proportion to their economic importance. This should mean a general lowering of yields across the single-currency area, and a further narrowing of Spanish and Italian bond spreads.

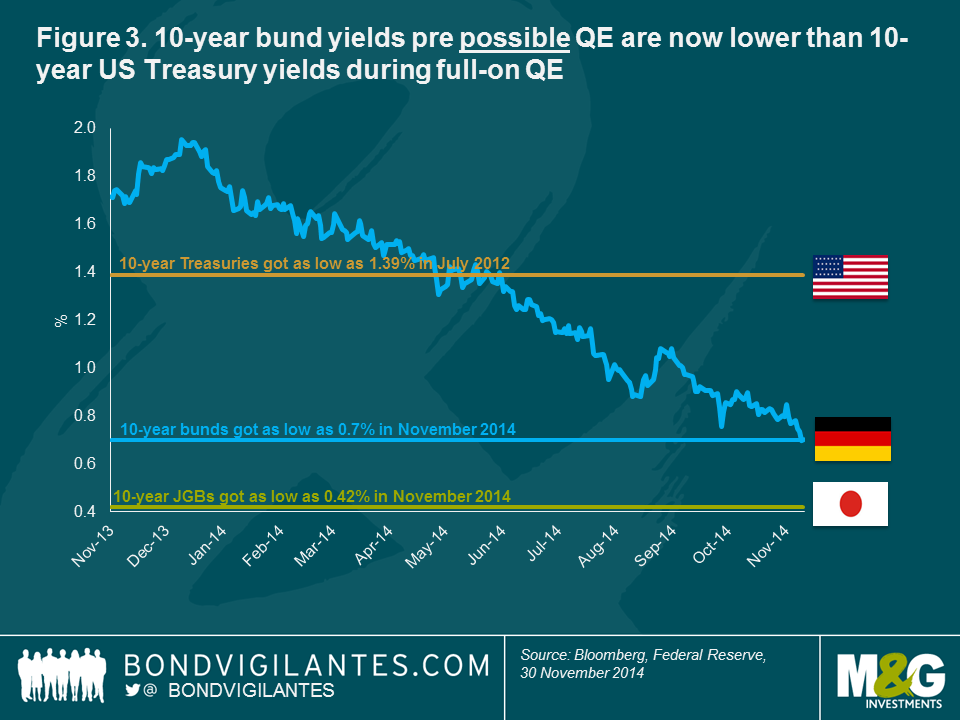

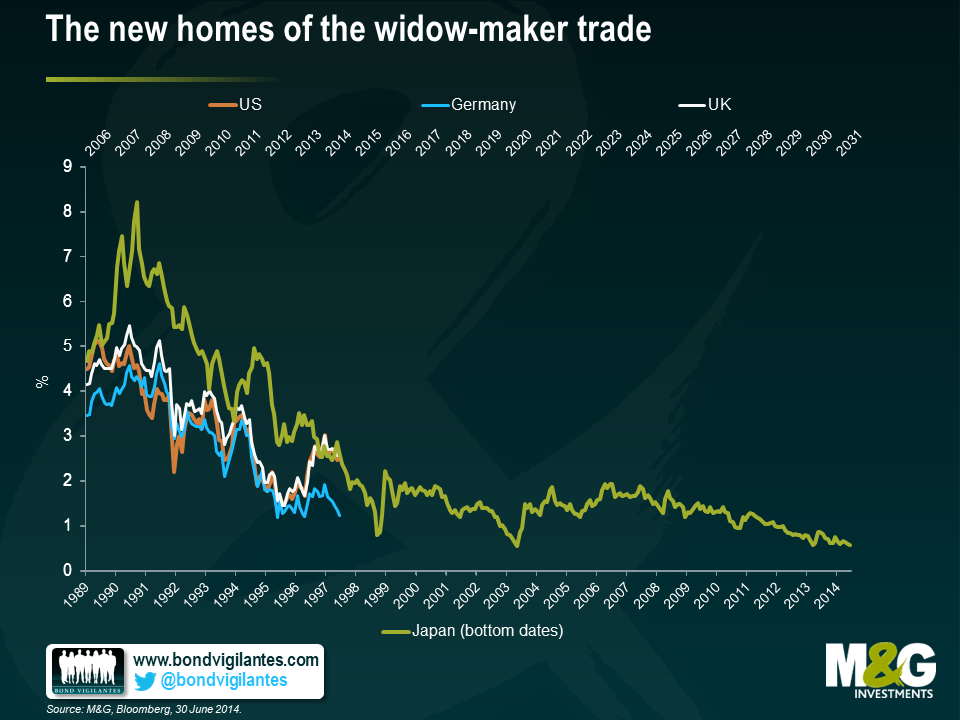

It’s clear though that bond markets have already discounted a significant QE programme from the ECB. The 10-year bund yield at 0.7% is already well below the sub-1.5% that US 10-year Treasury yields got to in 2012 at the peak of the Fed’s QE spree, and is not far from the 0.4% that Japan got to three decades into its economic crisis and after QE, zero rates and prolonged deflation (see figure 3).

But given how low core eurozone bond yields have fallen without full-blown QE, what real impact could this have? Deflation has come to Europe despite ever cheaper borrowing costs for the public and private sector. Its biggest impact just might be through the currency.

The Rise and Rise of Cocos

The biggest growth area for Europe’s bond market in 2014 has been hybrid securities – instruments with cryptic names such as CoCos (contingent capital notes) and AT1s (additional Tier 1 notes). Their rise reflects a wider drive to raise new capital following major regulatory changes designed to reduce the risk of governments needing to bail out banks in times of financial stress, as was the case in the financial crisis. The regulations include new capital requirements imposed under Basel III.

CoCos and their kind are finding popularity with banks and regulators alike due to the way that they combine features of equity and debt and can be deeply subordinated within capital structures. As this suggests, they are complex financial instruments that require significant analysis in order to invest. This has been recognised in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), which moved to restrict their sale to the mass retail market in October.

We believe that when purchased at an attractive price, CoCos can, on a selective basis, be a welcome source of additional risks and returns within a diversified bond portfolio. In our view, it is important to have a large and dedicated team of financial credit analysts that can conduct fundamental analysis, meet company management and understand the possible risks involved in investing in such instruments. Investing in CoCos bears specific risks that go beyond the risks of corporate bonds and include: trigger-level risk, coupon cancellation risk, capital structure inversion risk, call extension risk, and valuation risks. In addition, CoCos are an emerging asset class and it is still difficult to predict how they will perform in a stressed environment.

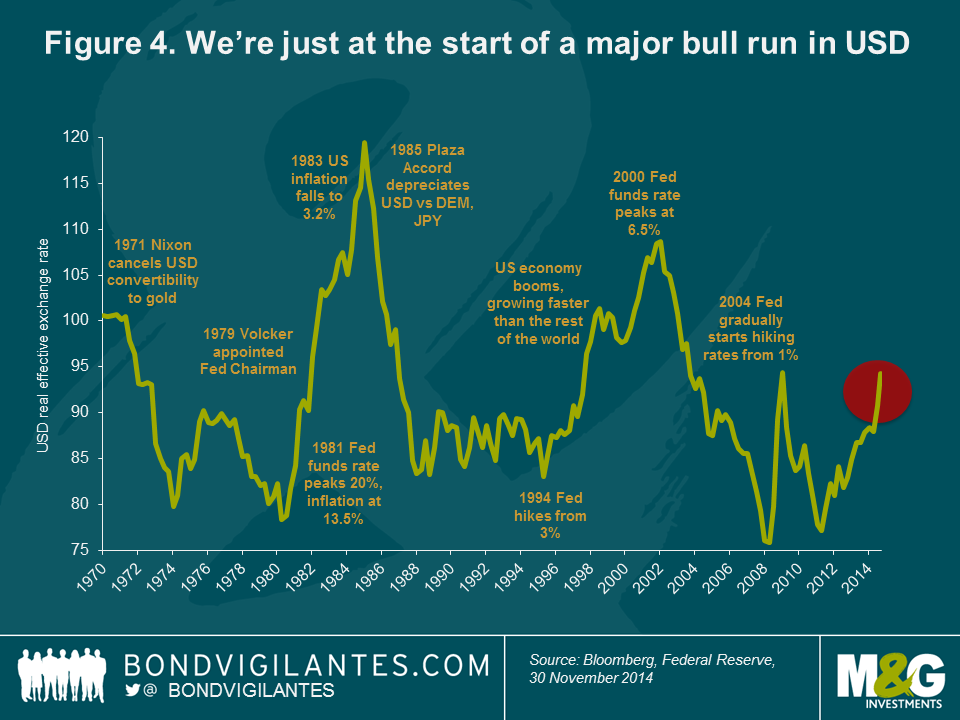

Financial markets tend to regard QE as a debasement of the currency – just look at the yen since Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced the sharpest of his three arrows, the huge expansion of the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet, or conversely at the strength of the US dollar as the currency markets anticipated the end of Fed bond buying. It’s likely that both yen and euro weakness will continue into 2015 and beyond. Whilst the US dollar has seen a significant bounce from its weakness in the middle of 2014, its current strength looks minor compared with historical bull markets.

Bull market for the US dollar ahead

The US dollar is not only supported by the relative shrinking of the Fed’s balance sheet compared with those of the Bank of Japan and the ECB, but more fundamentally by its stronger growth potential over the coming years, the likelihood that the US will be the first of the large economies to hike rates, and also by an improvement in its current account. Whilst the US remains a deficit economy, importing more than it exports, the dramatic turnaround in its energy position means that within the next decade or so it could become self-sufficient in energy – and its current account deficit all but disappears (see figure 4).

We continue to like the US dollar, but not its government bond market. One way to take advantage of expected dollar strength, Fed rate hikes and improving US corporate and banking health is to buy floating rate notes (FRNs). Unlike traditional bonds, these instruments don’t have fixed coupons and instead pay a rate of interest linked to money market rates. So as the Fed raises rates, probably in the middle to second half of 2015, the coupon on the FRN rises too.

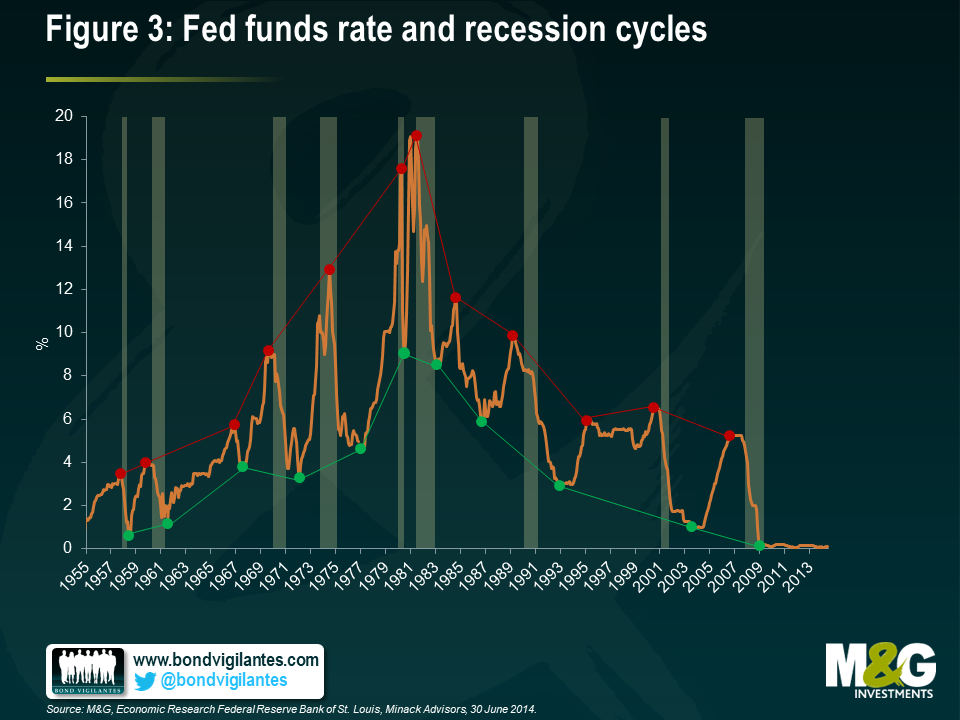

Federal Open Market Committee member estimates regarding the long-run Federal Reserve funds rate as shown in its so-called ‘dots’ chart are helpful when drilling down into how tightening might unfold (see figure 5). In effect, this provides a guide not only to the direction that bond yields should go, ie, upwards, but also by how much. Based on the dots, and given that forward-looking US Treasury yields were around the top dots 12 months ago, we found that the start of 2014 was a good time to add duration. Fast forward to year-end, and taking into account the significant year-to-date yield rally, and the reverse applies, with short duration now looking the right stance (see figure 6).

Might there come a time to go negative duration and could 2015 be that time? Possibly, although we should remember that negative duration implies a negative carry, meaning you have to be right simply to break even. In other words, yields have to rise for returns to stand still. However, a proper bear market for fixed income assets seems unlikely before inflation starts to rise back up towards target. With wage rises still very low, despite certain signs of tightening in parts of the US labour market, the timing of such a sustained inflation pick-up remains uncertain.

Developed world challenges

While the outlook for the UK economy remains relatively solid, there has been a significant downgrading of expectations over the past few months and the UK has fallen back from the position it held for much of the year as front-runner for interest rate hikes. As David Cameron pointed out in early November, “red warning lights are once again flashing on the dashboard of the global economy” in the shape of the eurozone teetering on the verge of another recession, slowing emerging market growth, little progress with global trade talks and geopolitical risks.

UK Referendum Fever

Prime Minister David Cameron’s pledge back in 2013 to give UK voters an in–out referendum on European Union membership has been gaining prominence this year, particularly after Scotland’s own close-run vote against independence from the UK in September.

Cameron has adopted an increasingly critical stance on the EU in recent months, as he tries to counter the rising popularity of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), whose campaign is centred around leaving the bloc. Should the Conservatives be returned to power following parliamentary elections in May 2015, an EU referendum would take place by 2017.

The relative narrowness of the Scottish vote (in the end, around 55% voted in favour of remaining part of the UK, although opinion polls in the weeks running up to the election were far closer) caused sterling to weaken and the stocks of a number of Scotland-headquartered firms to sell off.

While short-lived – and over very quickly following the announcement of a victory for the ‘no’ camp – the volatility gave markets some insight into what could happen in the run-up to an EU referendum. Should the UK vote in favour of ‘Brexit’, as it has become known, then all bets could be off. Although most voters currently claim to be in favour of continued EU membership, the Scottish referendum provides an example of how voting intentions can remain fluid right up to the day of the vote.

The UK’s significant reliance on the eurozone, in particular, is already making itself felt in slowing manufacturing and export data. Added to which, with parliamentary elections due in 2015, and the possibility of ‘Brexit’ (British exit from the European Union, see box entitled UK referendum fever) becoming more widely discussed, 2015 looks likely to be beset with uncertainty.

We have said it before, but the UK’s ongoing very large current account deficit remains a key concern. We continue to view the currency as being fundamentally overvalued on this basis, and such large deficits – as well as being unsustainable from an economic perspective – have historically also preceded a sterling crash.

Elsewhere in the developed world, we remain short the yen, as sentiment is likely to remain adverse against Japan’s persistent economic growth problems and need for ongoing stimulus. However, a combination of weak oil prices, and the recent announcement that the next scheduled consumption tax hike has been put on hold could yet combine to turn Japan into the surprise growth story of 2015.

Emerging markets: support remains

Emerging bond markets have generally performed well over the past 12 months, despite investors’ focus on the winding down of QE in the US and the bouts of volatility caused by geopolitical concerns. Against these factors, sentiment towards the asset class has benefited from persistent very low interest rates and benign inflation conditions in developed economies, which have supported demand for higher yielding assets such as emerging market bonds.

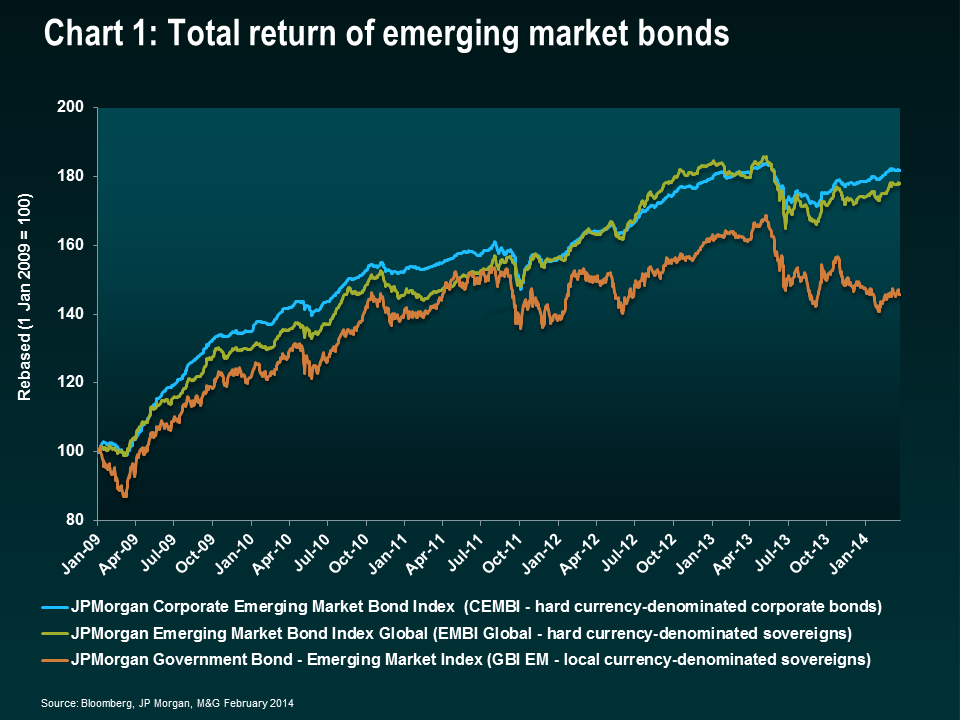

The fast growth of the emerging corporate bond market in recent years is widening the opportunity set in the asset class. The hard currency corporate bond sub-asset class has doubled in size since 2010, and is now worth over US$1.3 trillion – on a par with the US high yield market. With the inclusion of local-currency bonds, the Bank of International Settlements estimates that the total emerging market corporate bond market was worth nearly US$4 trillion at the end of 2013.

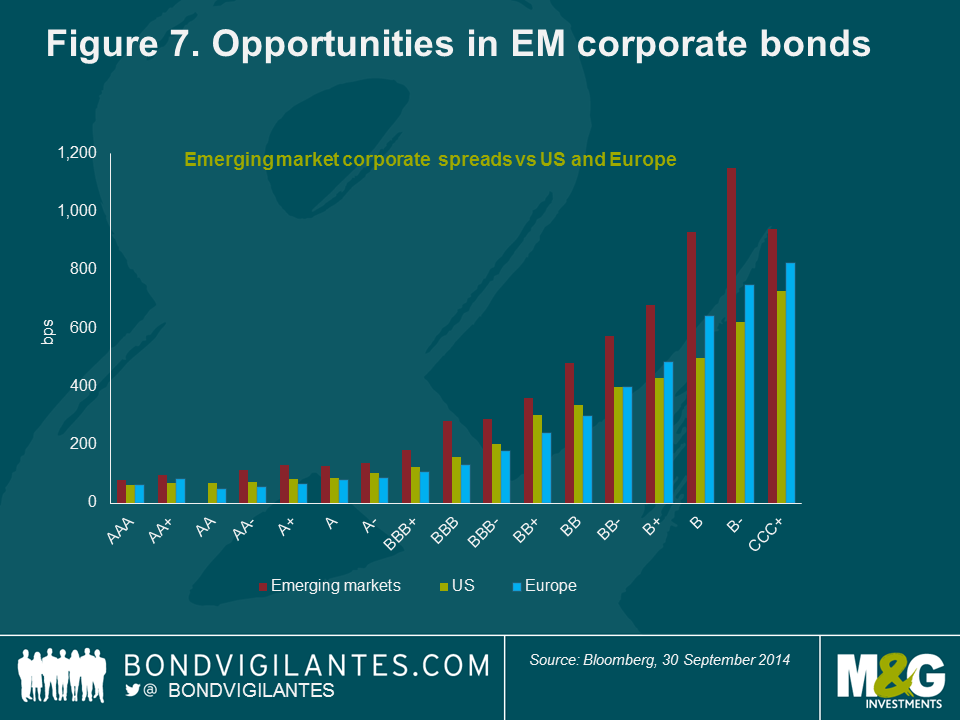

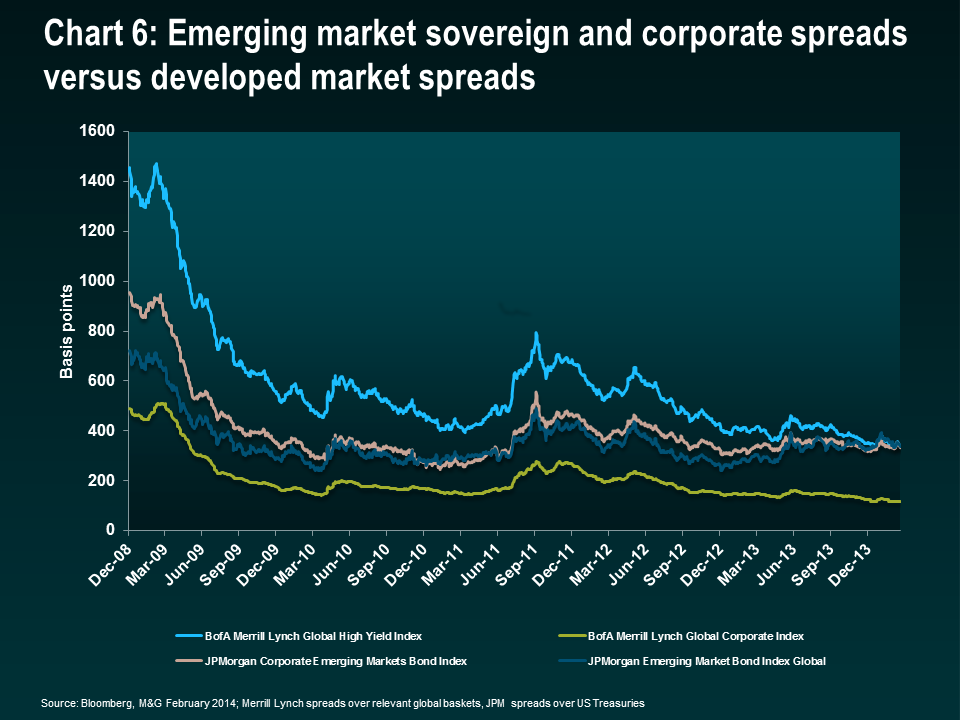

From a current valuation perspective, emerging market corporate bonds can be attractive relative to their developed market counterparts after steadily decent performance from the latter. However, investing on a selective basis with careful and thorough credit research remains key. Figure 7 shows that for a similar bond rating class, emerging market corporate credit is offering higher spreads than in the US and Europe, suggesting that investors are being compensated for the credit risk as well as receiving a premium for investing in emerging market assets.

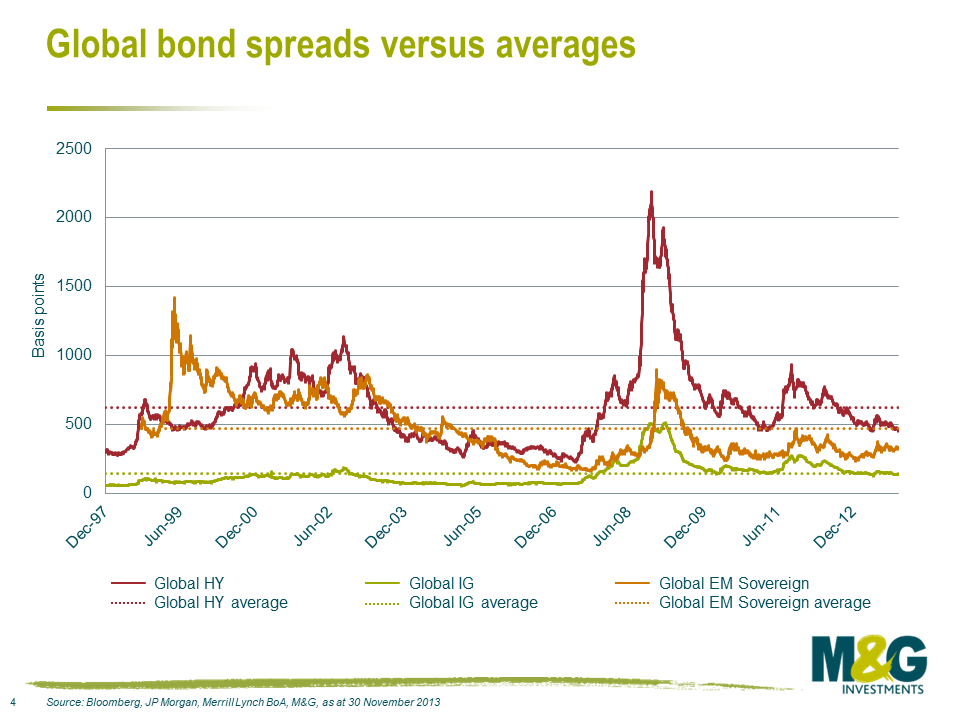

Credit: closer attention to quality now needed

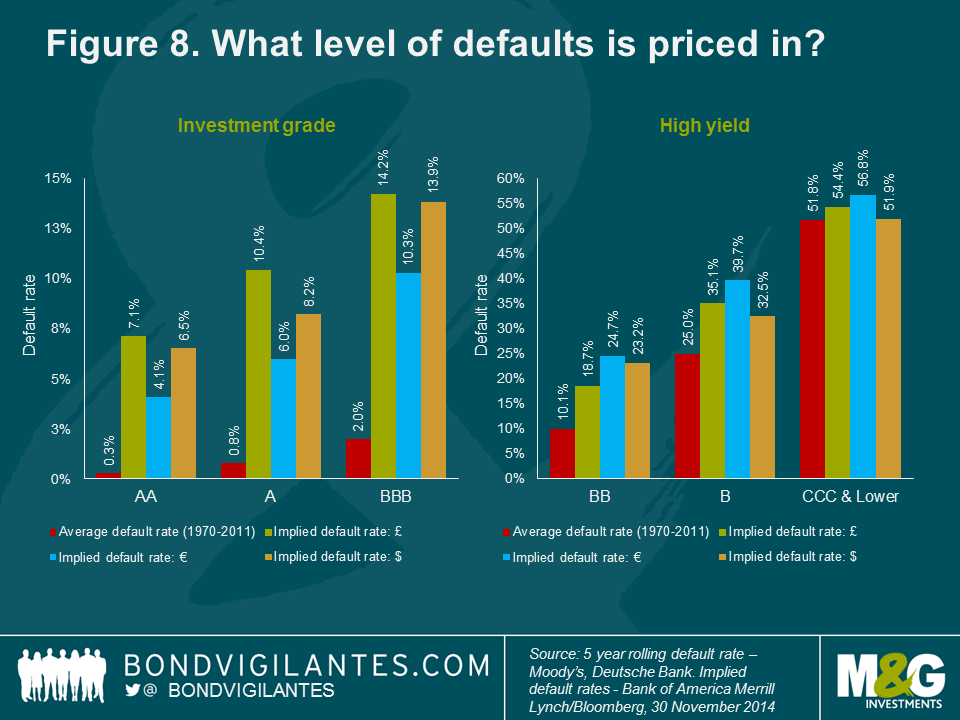

The easy money has clearly already been made in corporate and high yield bond markets. Since the height of the credit crisis, spreads on investment grade have tumbled from a peak of 511 basis points (bps) in 2008 to around 123 bps today, and in high yield, from 2,193 bps to 488 bps over the same period. The good news is that in every rating bucket except for CCC, investors are still being overcompensated for default risk – in other words, credit spreads imply a higher level of defaults than we would expect to see (see figure 8). The bad news is that most of that excess spread is likely to be a premium for illiquidity (see box entitled The price of liquidity), which is not necessarily a problem for long-term investors, but could be a potential source of volatility in the shorter term.

While there are signs of some bad behaviour returning to credit markets, this is on a much smaller scale than in the years before the credit crisis in 2008. Nevertheless, animal spirits do appear to be returning – especially in the US – as evidenced by rising levels of corporate debt, increased merger and acquisition activity and an upsurge in the issuance of lower rated CCC bonds and ‘payment-in-kind’ debt (PIK notes). Dividend payments and share buybacks are also increasing, although healthy corporate profit margins appear to be having only a limited impact on capital expenditure so far, which is a shame for global growth.

While the global default rate is still extremely low, a few warning signs probably suggest that it is time to start paying closer attention to deteriorating credit quality. Overall, companies still have lots of (arguably too much) cash on their balance sheets, but there are a few signs that profit margin growth has reached an end.

A number of high yield businesses have run into problems this year, and while each has been the result of specific issues which were unique to those companies, it does perhaps highlight a general trend of complacency amongst high yield investors. On the other hand, an increase in distressed debt can be a source of opportunities; where we believe the underlying business is robust and the bondholder’s legal position strong, we many occasionally invest in distressed debt instruments.

As the experience of the past few years has aptly demonstrated, making bold predictions for bond markets for the coming year requires no small measure of bravery. Nevertheless, with substantial volumes of QE still on the horizon in a number of globally significant economies such as Japan and the eurozone, the prospect of deflation rather than inflation keeping central bankers awake at night, and the timing of interest rate hikes being pushed out in nearly all economies, it does not need a huge leap of faith to say that conditions for bond investors currently look relatively benign. Equally, as the start to 2014 showed, all it takes is a few stormy months – literally or figuratively – for all best estimates to fall by the wayside.

The Price of Liquidity

Bond trading used to be an integral part of the business model of large banks. That changed after the 2008 financial crisis, when a storm of regulation forced banks to de-lever their balance sheets and retreat from secondary market-making activities. The past few years have seen banks relatively less willing to hold corporate bonds on their own balance sheets until a buyer or seller can be found.

Investors are justifiably worried about what will happen if everyone decides to sell corporate bonds en masse. In an extreme scenario, a complete absence of secondary market activity would impair fixed income managers’ ability to sell their corporate bond holdings, regardless of whether the securities were held in mutual funds, exchange-traded funds or institutional mandates.

The liquidity premium on offer in credit markets is one of the reasons investors can expect a higher return relative to investing in deep and liquid government bond markets. When liquidity was excellent in 2006–07 and credit spreads were very tight, an investor in corporate bond markets was not being paid for liquidity risk and subsequently suffered greatly when corporate bond spreads widened to all-time highs in 2008. The deterioration in liquidity contributed to the large sell-off in corporate bond markets at that time.

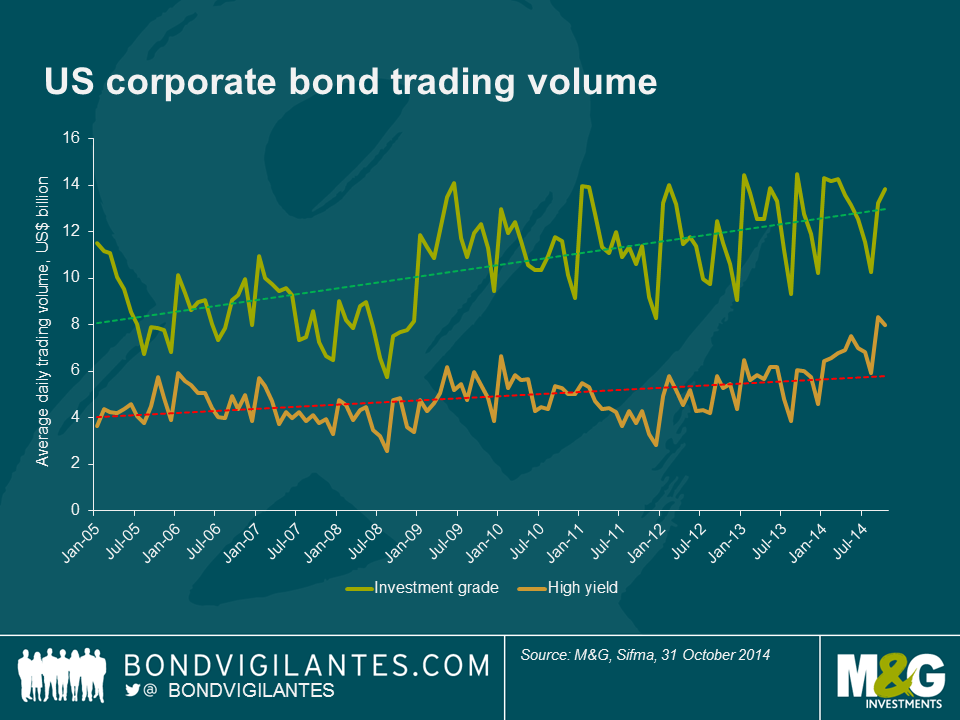

The underlying dynamics of the marketplace make for interesting reading. Secondary-market corporate bond turnover in the US has actually now increased to above pre-crisis levels. As shown in the chart below, average daily transaction volumes have risen from less than US$15 billion in 2007 to US$22 billion in October 2014.

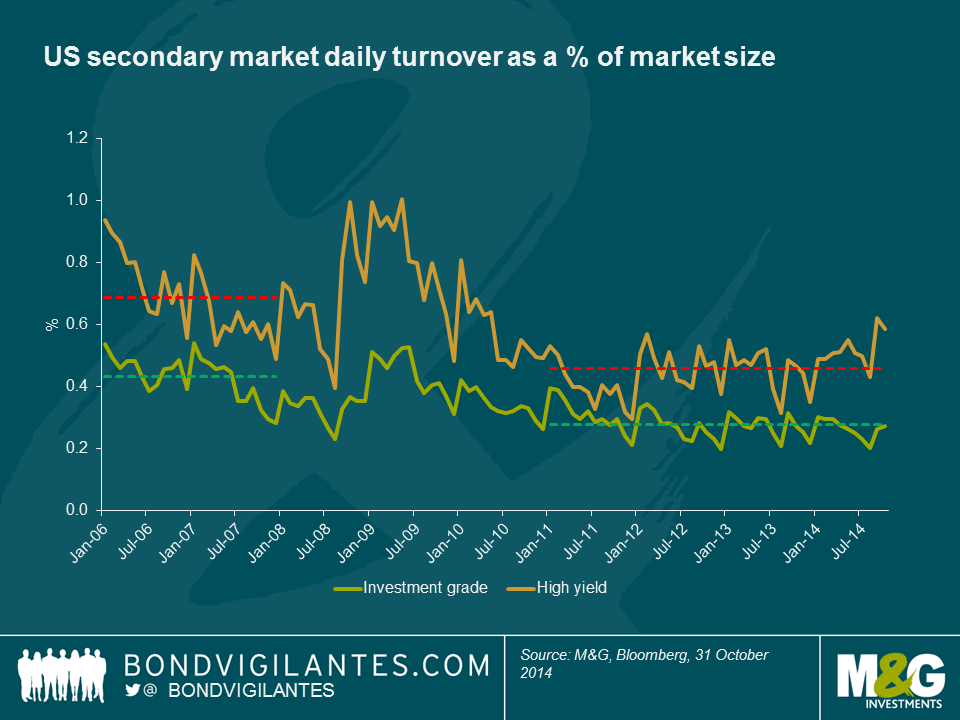

However, global corporate bond markets have grown significantly over the past seven years. Thus, when looking at corporate bond trading as a percentage of the total market, rather than in absolute terms, the steady decline in the share of outstanding corporate bonds that trade on the secondary market becomes evident. Secondary daily market turnover in US investment grade has averaged 0.28% from 2011 to today, a decline from 0.43% in the period between 2006 and 2007. Interestingly, during the financial crisis period – a time most perceive as a very poor liquidity environment – daily market turnover spiked to 0.5% of the US investment grade and 1.0% of the US high yield market as investors sought to exit positions. Whilst liquidity has fallen relative to pre-crisis levels, there is no evidence of a recent, more precipitous, drop in secondary market liquidity.

That said, there have been days in 2014 where a lack of liquidity has been blamed for abnormal market moves. On 15 October, the yield on the benchmark 10-year US government bond plunged 33 basis points to 1.86% before traders stepped in. Yields then rose back to 2.13%. This ‘flash crash’ may have been the result of some large market participants capitulating on short duration calls, alternatively computer-driven trading has been suggested as another reason for the price action in government bonds as yields fell below the key support level of 2.0%. At the end of the day, almost US$1 trillion worth of Treasuries had been bought and sold, showing that liquidity was available. The question, as in all distressed markets, was whether investors were buying and selling at reasonable prices.

Harvesting the liquidity premium is one of the ways for bond fund managers to generate higher returns for investors. Of course, the risks of owning lots of illiquid paper are higher in a poor liquidity environment where it may be difficult to meet client redemptions. To mitigate this risk, managers can undertake measures that include (but aren’t limited to) investing in government bonds; holding short duration, high quality corporate bonds; holding a cash or cash-like buffer; and emphasising diversification.

Liquidity conditions today appear increasingly linked to the direction of spreads (decent in times of narrowing spreads, and correspondingly poorer as spreads widen). We think a lack of liquidity in and of itself is not necessarily something to be feared. That said, we actively monitor liquidity risk across our bond funds, and it is a key reason why we integrate liquidity management into our investment process.

With many of the conditions for the economy to normalise now met, the point at which interest rates also begin to normalise is getting closer.

Bank of England Governor Mark Carney, Liverpool, 9 September 2014

… with the economy getting closer to our objectives, the FOMC’s emphasis is naturally shifting to …. the question of under what conditions we should begin dialling back our extraordinary accommodation.

Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen, Jackson Hole, 22 August 2014

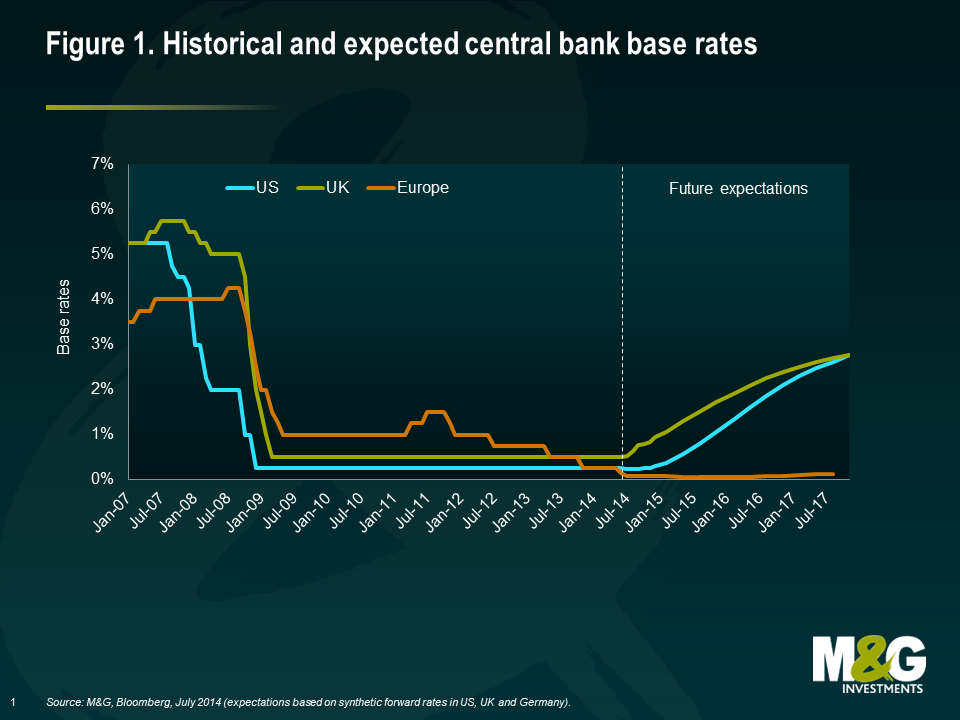

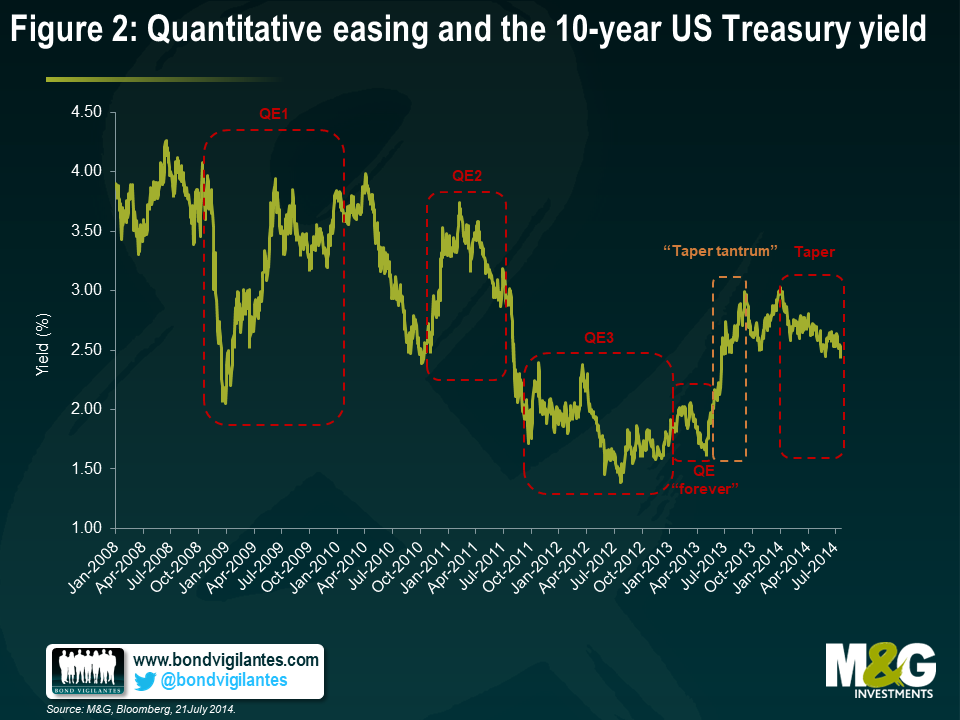

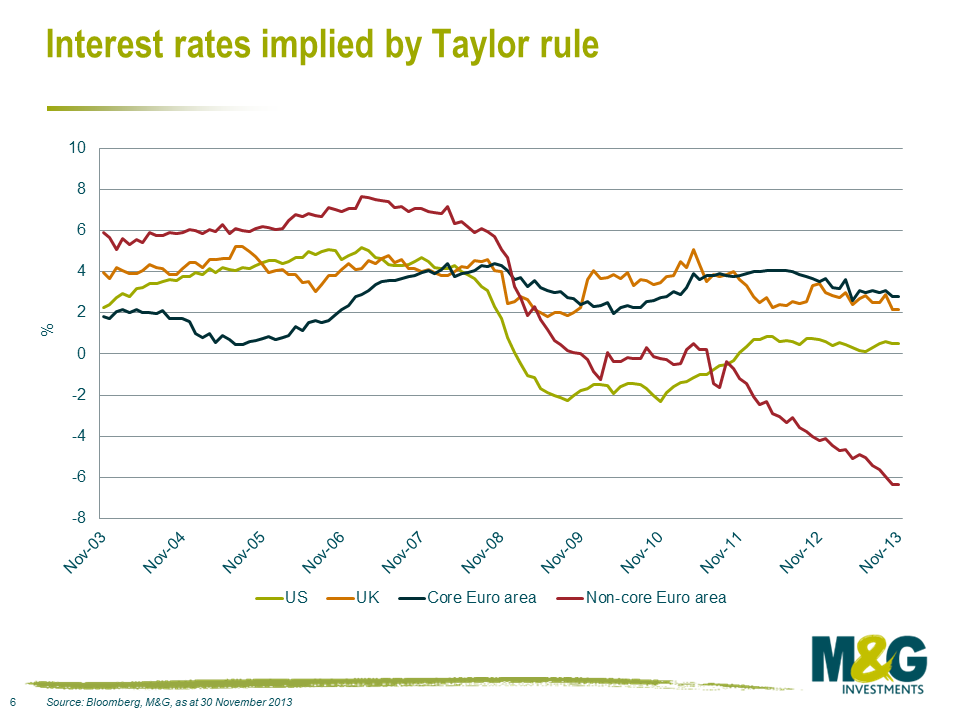

We are entering a new era for interest rates in the developed world. The extended period of ever looser monetary policy is starting to draw to a close. In the wake of the tapering of quantitative easing (QE) from the Federal Reserve (Fed), investors now expect to see the first interest rate hikes in many years, initially in the UK and shortly afterwards in the US (see figure 1). The principal focus of the debate is over the questions of “when?” and “how fast?” interest rates should rise, not “if?” For bond investors in particular, this transition has thrown up a lot of difficult questions. Having benefited greatly from falling yields and tightening credit spreads, the move to a more hawkish cycle will create many more headwinds and challenges when it comes to delivering returns for many fixed income asset classes.

Consequently, any product or instrument that can help investors navigate this environment has rightly been receiving a lot of interest and attention. In the latest in our series of the Panoramic Outlook, we will focus on one such instrument, the high yield floating rate bond. In recent years, this instrument has gained popularity with many issuers and the market has grown to a total US$44 billion.

A high yield floating rate note (FRN) has two key defining features: (1) a floating rate coupon that is automatically adjusted in line with changes in interest rates; (2) a relatively high credit spread that reflects the additional credit risk of a non-investment grade issuer.

It is the combination of these two features which not only enables investors to receive an attractive income stream now, but also allows them to benefit from higher coupons should interest rates increase with no associated loss to capital. This last element, the lack of a hit to capital in a rising interest rate environment, is the key difference to the traditional universe of fixed coupon bonds which suffer from price declines as yields move up.

In this issue, we will take an in-depth look at the characteristics and make-up of the high yield floating rate bond market. We will also consider the key drivers of returns, as well as some of the risks and how these can be managed.

High yield floating rate bonds 101

The key features of high yield floating rate bonds can be summarised as follows:

- It is a bond issued by a company that has a below-investment grade credit rating

- The coupon, usually paid quarterly, is made up of:

- a variable component which is adjusted in line with a money market reference rate, typically every three months (throughout this article we will refer to this measure as ‘3-month Libor’)

- a credit spread, which is fixed for the life of the bond and reflects the additional credit risk of lending to a company

- The bond has a fixed maturity (typically 5-7 years at the time of issue)

- The bond is a publicly traded instrument that can be bought and sold like any other corporate or high yield bond

- As an example, suppose that a 5-year bond is issued with a coupon of 3-month Libor + 450 basis points (bps). For the first year, 3-month Libor is 50bps, so the coupon is 500bps (or 5%) over that period. In the second year, 3-month Libor rises to 75bps, so the coupon increases to 75+450 = 525bps, or 5.25%, during that period.

Market characteristics

| Table 1: High yield floating rate market compared with other fixed coupon bond markets | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | Global High Yield Floating Rate | Global Government Bond | Global Corporate | Global High Yield |

| Average maturity (years) | 4.5 | 8.9 | 8.7 | 6.1 |

| Effective duration (years) | 0.03 | 7.2 | 6.2 | 4.2 |

| Spread duration (years) | 2.1 | 6.9 | 6.1 | 4.1 |

| Face value (US$ billion) | 44 | 23,081 | 7,964 | 2,057 |

| Yield to maturity (%) | 4.5 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 6.1 |

| Spread (vs government bonds, bps) | 400 | 14 | 110 | 435 |

| Composite rating | B1 | AA1 | A3 | B1 |

| Source: M&G, BofA Merrill Lynch, 5 August 2014. |

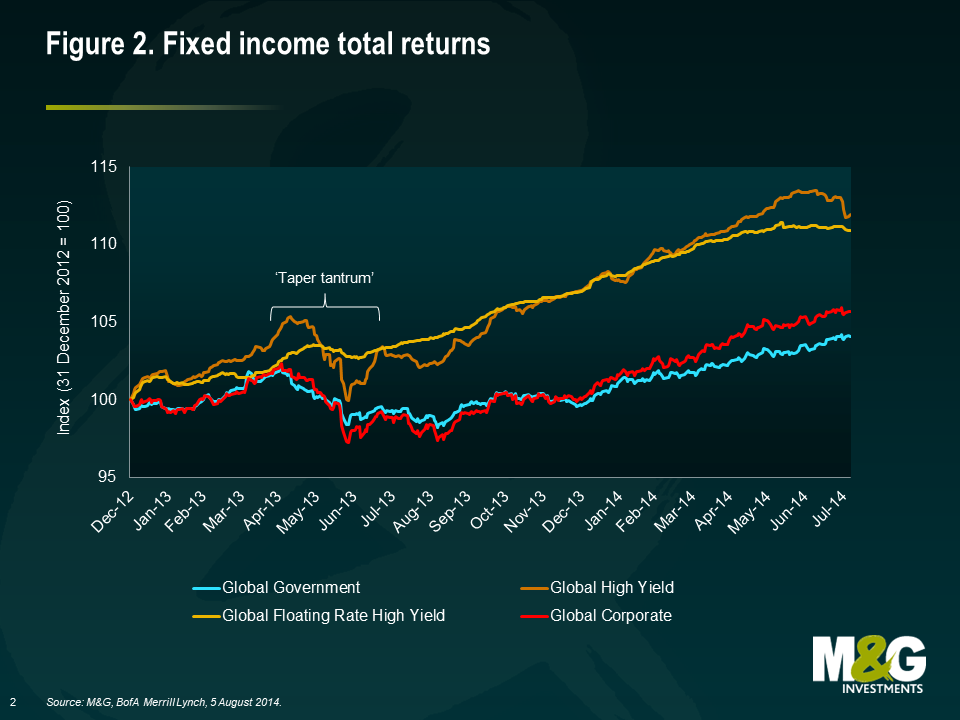

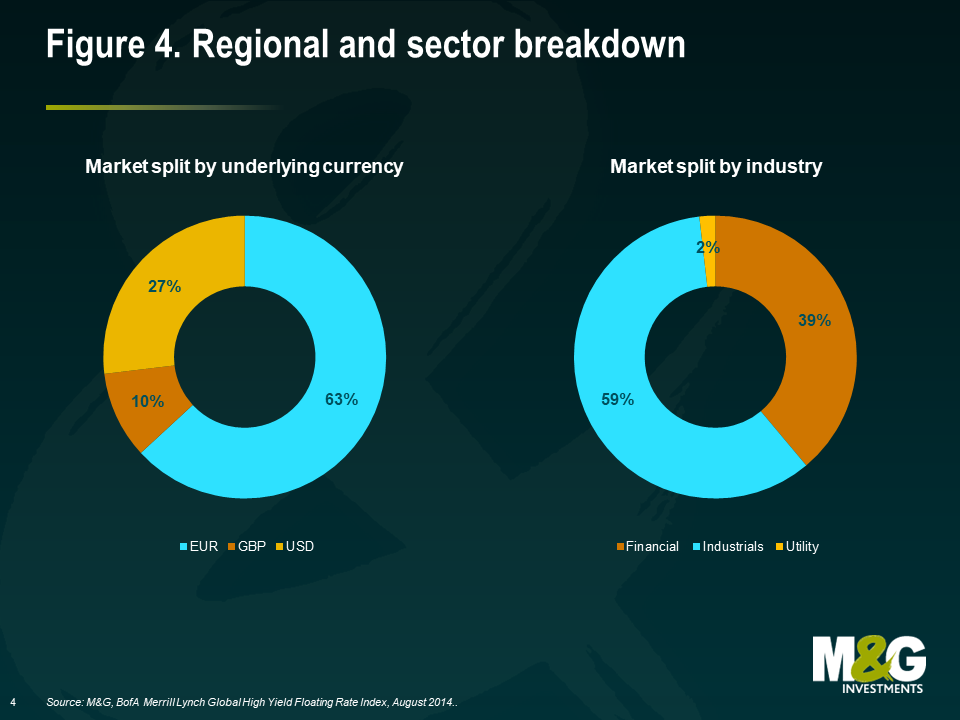

Table 1 highlights some of the characteristics of the high yield floating rate market and compares it with the more traditional government, corporate and high yield fixed coupon bond markets using data from Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s fixed income indices.

In terms of credit risk (measured by the composite rating) and credit spread (the yield premium above government bonds that compensates investors for the higher risk of default), the high yield floating rate market is very similar to the traditional high yield market. This is to be expected as there is a great deal of commonality between the two in terms of underlying issuers.