QUASI-SOVEREIGNS IN EMERGING MARKETS

A growing asset class

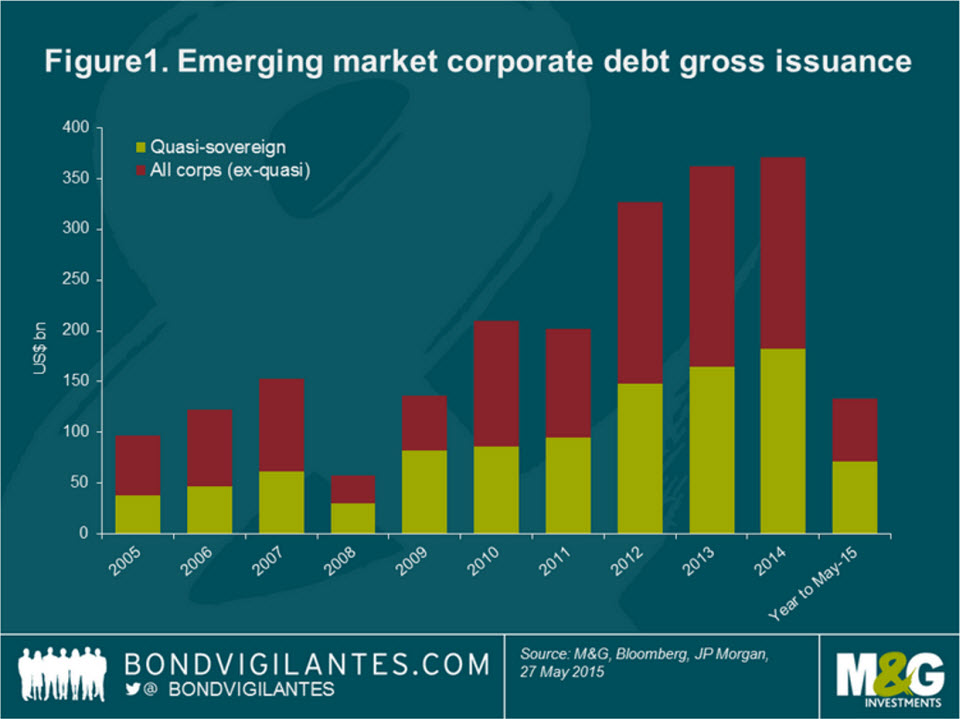

Emerging market (EM) corporate debt has been the fastest-growing segment of fixed income assets over the past decade, rising by nearly seven times since 2005 with external EM corporate debt currently worth c.US$1.7 trillion – larger than the US high yield credit market. One significant contributor to this growth in EM corporate debt in recent years has been the increasing share of quasi-sovereign issuance, which accounted for 49% of the US$371 billion of bonds issued in 2014 (see figure 1). Helped by this trend, EM quasi-sovereign bond stock of US$783 billion surpassed EM sovereign-only bond stock of US$747 billion in 2014 for the first time.

While the definition varies across market participants, an entity or a company is typically defined as ‘quasi-sovereign’ if a government owns either more than 50% of its equity or more than 50% of the company’s voting rights.

Historically, developing countries have been using quasi-sovereign issuance to fulfil policy function, develop the hard-currency corporate debt market, or promote international expansion of leading domestic players. As at the end of June 2015, there were about 170 quasi-sovereign issuers in emerging markets*, more than 60 of which were fully owned (such as Petróleos Mexicanos, or Pemex, in Mexico) or issued bonds explicitly guaranteed by their respective governments (for example, Magyar Exim Bank in Hungary).

* Estimate based on various EM bond indices.

Given the commodity-based nature of emerging markets, oil & gas is unsurprisingly the most represented sector within the quasi-sovereign bond universe, followed by financials, utilities and metals & mining.

In terms of countries, China has been by far the largest issuer of quasi-sovereign debt in the past five years, with over US$170 billion of hard-currency bonds currently outstanding. Following this market in absolute size are Russia, Brazil, Korea, the UAE and Mexico. However, on a relative basis (measuring quasi-sovereign bonds as a percentage of total hard-currency bond stock of a country), Venezuela, several Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members (namely United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Saudi Arabia), and Kazakhstan, are ahead of Russia and Korea, and even China.

The largest single issuers are Latin American oil & gas giants Pemex and Petróleo Brasileiro (Petrobras), which altogether represent nearly 15% of total quasi-sovereign bond stock in emerging markets (see figure 2).

One of the best risk-adjusted returns in EM

EM quasi-sovereign bonds have generated good returns since 2005. According to JP Morgan, they generated an annualised return of 6.05%** between 2005 and 2014. With a Sharpe ratio of 0.51 during the same period, this sub-asset class has delivered the best risk-adjusted return within EM (hard-currency) debt over the past decade. The good returns coincided with a prosperous period for emerging markets, characterised by improving macroeconomics in developing countries and relatively healthy fundamentals in the ever-growing corporate debt universe. However, times have arguably changed for emerging markets and macro headwinds have resurfaced in the likes of a stronger US dollar, low commodity prices, fears of a hard-landing for the Chinese economy and EM outflows on the back of the long-awaited US interest rate hike, amongst others.

**Evolution of Quasi-Sovereigns in the EMBI Global, JP Morgan, February 2015

Against this backdrop, an important impact for quasi-sovereign credits has been the increasing differentiation made by investors in terms of corporate fundamentals – an analysis that was somehow lacking, based on the assumption that sovereign analysis was sufficient and that quasi-sovereign corporate fundamentals almost did not matter.

Assessing the credit risk of quasi-sovereign issuers

In most instances, a quasi-sovereign usually has a so-called ‘implicit’ guarantee from its government, but that does not mean it will necessarily obtain an ‘explicit’ guarantee on its bonds. Therefore, bond investors must make sure they carefully examine bond documentations to assess whether or not they are invested in a bond explicitly guaranteed at the sovereign level. For example, while SriLankan Airlines, the national carrier, has weak credit fundamentals, its bonds are nevertheless rated B+ by Standard & Poor’s, in line with Sri Lanka’s government rating, because of the unconditional and irrevocable (hence, explicit) guarantee offered by the government on SriLankan Airlines’ bonds. A change of control clause is also critical in assessing the level of protection for bondholders to a change in the government ownership. Again, credit documentation due diligence is required to identify these risks.

Another key element for assessing quasi-sovereign risk is the level and likelihood of government support in case of liquidity woes. The more strategically important a corporate is to a country, the more likely a government will be supportive. This is the reason why there is a wider definition of quasi-sovereign – albeit less used by market participants – which includes privately owned companies that are of extreme importance to the economy and would likely be supported by their respective governments. This is the case, for instance, with privately owned Alfa-Bank in Russia. On the contrary, a high level of government-ownership does not necessarily mean that a government will be supportive in a default scenario; therefore, assessing the willingness – on top of the ability – of a government to step in is crucial. As an example, in 2009, the state-controlled Dubai World conglomerate ran into financial trouble and the government of Dubai clearly stated at this time that it had no legal obligation to financially support the company, adding that: “the lenders should bear part of the responsibility”. What was seen as a safe quasi-sovereign investment finally resulted in a painful and lengthy restructuring of the debt for bondholders.

The third factor in quasi-sovereign risk assessment is, of course, corporate credit risk. This encompasses the same work as for ‘pure’ EM corporates – that is, sector outlook, operational performance, credit metrics, management analysis, foreign exchange mismatch, refinancing risk analysis, covenants, bond recovery rate estimates in case of default, etc – in order to measure the so-called ‘standalone credit profile’ of an issuer. Good practice consists of assessing a standalone rating of the intrinsic credit, excluding extraordinary support of a government in a default scenario, but including any daily or punctual government support in the daily operation of a company. Brazil-based quasi-sovereign Petrobras, for example, is rated Ba2 by Moody’s, which assumes a high likelihood of government support (Brazil is rated Baa3 by the rating agency), but is only rated three notches below at B2 on a standalone basis (baseline credit assessment), following the deterioration in Petrobras’ fundamentals and the ongoing corruption scandal involving the company.

How quasi-sovereign bonds trade

To understand how EM quasi-sovereign bonds trade in the market, one important distinction investors make is the aforementioned level of government ownership and the presence or not of government guarantees, as the correlation of a quasi-bond to its sovereign component is highly dependent on these two elements. In general, spreads of quasi-sovereign issuers that are explicitly guaranteed or 100% owned by their governments are highly correlated to their respective sovereign spread. For example, this is the case for PEMEX (100% owned by Mexico) or oil & gas group Pertamina (100% owned by Indonesia), whose spread correlations with their respective sovereign bonds are 0.93 and 0.95. Bond indices, in general, make a case of this correlation and JP Morgan includes fully owned or explicitly guaranteed quasi-sovereigns in its EM hard-currency sovereign index (EMBI Global). The EM hard-currency corporate bond index (CEMBI) includes most quasi-sovereign issuers that are not 100% owned or not explicitly guaranteed by their respective governments. These latter bonds typically have a lower correlation to their sovereign curve, although the sovereign spread component is not negligible – for instance, Petrobras spreads have a correlation of around 0.5 with Brazil.

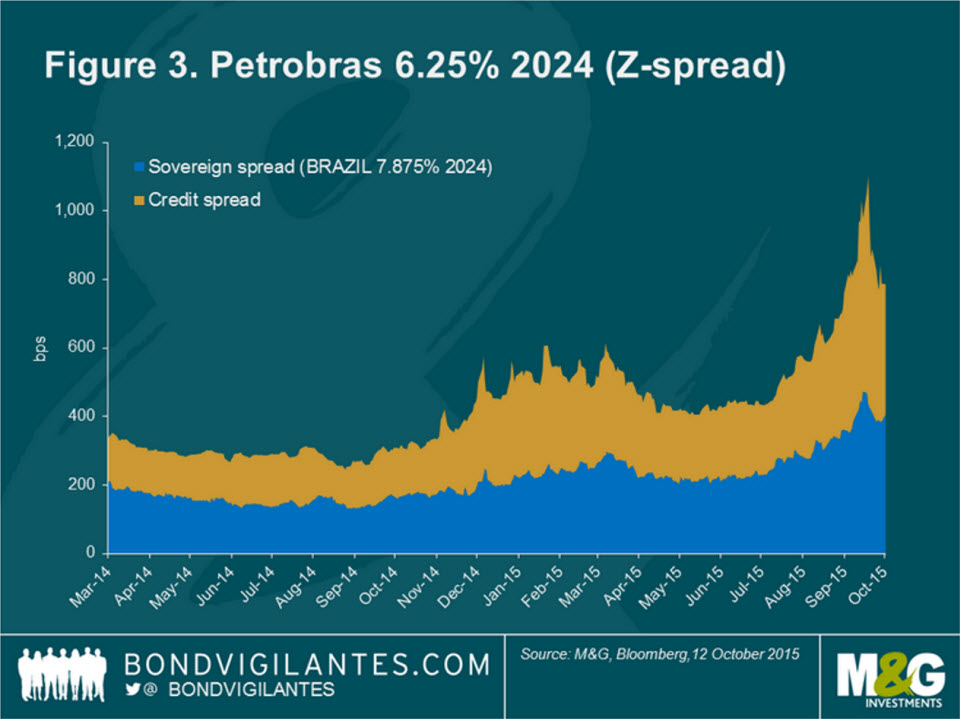

One widely used measure of valuation of quasi-sovereign risk is the spreads offered by hard-currency bonds to its sovereign spreads. With the exception of the Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) bonds, almost all quasi-sovereign bonds trade wider than their corresponding sovereigns since they include an additional layer of risk: corporate credit risk. (Figure 3 provides an example for Petrobras’ bonds yielding 6.25% maturing in 2024). Bank of America Merrill Lynch recently conducted an analysis of quasi-sovereign spreads on 20 of the largest issuers in the Eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa region (EEMEA) and Latin America, all at least 50% owned by their respective government. Interestingly, the study concludes that sovereign spreads account for an average of 55-60% of the total spread – hence, investors bear an average of 40-45% of credit risk on quasi-sovereign bonds. In theory, the weaker the standalone credit profile the higher the credit proportion of spreads, as it is the case for Petrobras, whose credit spreads account for more than 50% of the bonds’ overall spreads.

Emerging market headwinds have resurfaced

The deterioration of emerging market fundamentals has been an important theme in the past 18 months.

On the macro side, all key countries in key regions have shown a weaker tone: (i) Brazil for Latin America faces tremendous economic and political challenges, (ii) Russia for EM Europe is still subject to economic sanctions from the West due to its involvement in the Ukraine crisis, and (iii) China for Asia, which is trying to regain competitiveness by ways of devaluating the renminbi. In addition, low commodity prices have been affecting – albeit unevenly – a number of developing countries and the fear of the adverse impact of the long-awaited US interest rate rise on emerging market debt is also not helping to improve sentiment. On a positive note, the lower oil price context has been a welcome push to most net-importer Asian countries, while Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico are benefiting from a stronger US economy.

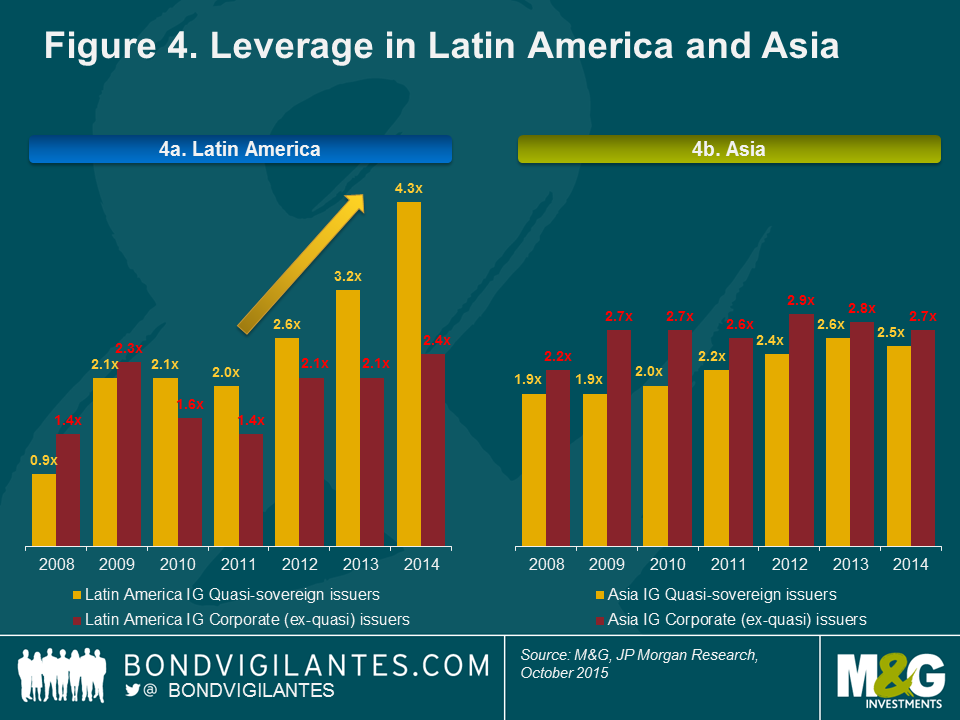

As often is the case in emerging markets, the trends of corporate fundamentals have hardly distinguished from the macro context and the overall picture is also on the downside. The very nature of quasi-sovereign issuers – being a mix of sovereign and corporate – has amplified the impact of the weakening macro backdrop on their fundamentals. For instance, weaker EM currencies in Latin America have had a significant effect on debt metrics for companies indebted in US dollar and with earnings in local currency – as can be seen in the rising leverage of Latin American investment grade (IG) quasi-sovereign issuers (see figures 4a and 4b). On the contrary, it is fair to say that Asian quasi-sovereign issuers have been very resilient despite the strong growth in quasi-bond issuance.

The adjustment on quasi-sovereign bond spreads should continue

Fundamentals have deteriorated in emerging markets, but bond spreads have also become more attractive in the asset class. Investors may, therefore, be considering whether some value has emerged. Our view is that this has not yet happened, based on the following considerations:

– Looking at spreads over sovereign, Asian quasi-sovereign bonds currently look the least attractive. While corporate fundamentals have been resilient across the region, spreads to sovereign have surprisingly not reacted to the deteriorating macroeconomic environment in Asia and averaged 98 bps as of 7 October 2015. It shows that Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are still seen as a safe haven for many investors on the assumption that China would not let a government-owned entity go bankrupt. Given China’s slowing economy and the lack of historical evidence of government bailout in case of default, a cautious approach to Chinese quasi-sovereign credit – with a thorough analysis of the standalone credit profile of issuers – seems essential nevertheless, in our opinion.

– In the EEMEA region, the spread pick-up offered by quasi-sovereigns over their respective sovereign looked attractive at the beginning of the year. However, the easing of geopolitics in Ukraine in the first half of 2015 has led to a strong outperformance and spread tightening of Russian quasi-sovereigns (and corporates) during the period.

– Finally, Latin American quasi sovereign spreads look unsurprisingly wide (average 286 bps as of 7 October 2015, well above historical levels, as shown in figure 5). But this is mainly the result of Brazil and, in particular, Petrobras. Adjusted for the largest country in Latin America, quasi-sovereigns spreads over sovereign excluding Brazil are actually relatively flat (only 25 bps wider) since May 2014. Arguably, they are offering little value as (a) Latin American sovereign bonds have widened by more on the back of the deteriorating macro environments, and (b) standalone credit profiles of quasi-sovereign issuers weakened significantly in the past 18 months.

Despite such factors, the pick-up in spreads of quasi-sovereign bonds above their respective sovereigns should continue to offer opportunities for investors looking for attractive yields, but who are also mindful of the rising default environment in the pure EM corporate bond space. Quasi-sovereigns, relative to pure EM corporates, offer a higher likelihood of government support due to their ownership and general strategic importance for their home countries. A selective approach is key against this backdrop, with careful sovereign and corporate credit research, while investors may also want to consider hedging strategies – such as buying credit default swap (CDS) protection in the respective country – in order to reduce sovereign risk.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox