China’s rising domestic bond defaults could spell offshore bond market rout

Chaori Solar and Baoding Tianwei will forever remain in the history of China’s bond market. In March 2014 the former became the first defaulter in the country’s onshore bond market whilst the latter turned out to be the first state-owned enterprise (SOE) default in China in April 2015. Since then, 24 other bond defaults occurred in the country, the majority of which in the manufacturing, metals and steel sectors, reflecting the country’s rebalancing act towards a service economy.

Around 90% of China’s corporate bond debt is denominated in local currency (Rmb) – the so-called onshore bond market. Two-thirds of this market is government-related debt. The remainder is corporates, of which 90% are SOEs. The IIF recently reported that it was the world’s third largest domestic market in value with a size of Rmb 48 trillion ($7.5 trillion) or 65% of GDP. Only the US $35 trillion (over 200% of GDP) and the Japanese $11 trillion market (250% of GDP) ranks in front of China. In principle, as a percentage of GDP, there is room for China’s onshore bond market to grow further. In practice, this is the tree that hides the forest considering that the country has a significant corporate loan problem with non-financial corporate debt of 125% of GDP. The very fact that there are increasing bond defaults in China’s onshore bond market – a relatively small universe composed of China’s blue chip companies – suggests that the main banks have been experiencing growing non-performing loan ratios.

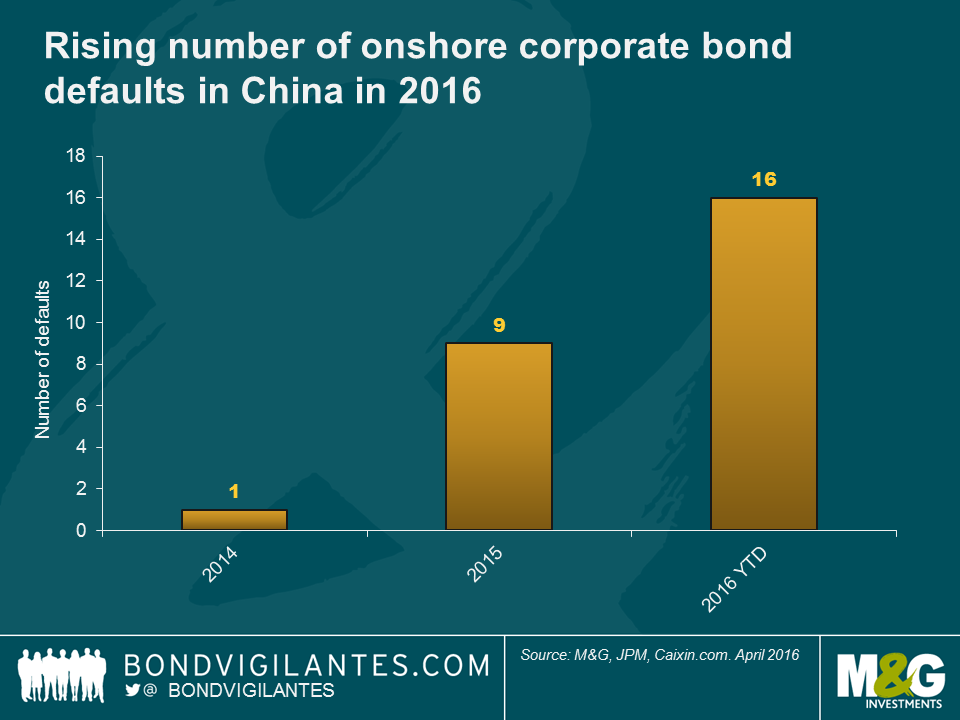

International bond investors would tend to see a rise in default rates as a natural healing process for China, allowing for greater credit differentiation. Therefore, one source of increased market concern is none other than the pace of corporate defaults this year and whether valuations do indeed reflect that risk. As can be seen in the chart above, there has been more corporate defaults in the onshore bond market year to date than in the previous two years. Another source of concern is the uncertainty about whether the government will continue to support state companies – which represent a large share of the onshore bond market. Back in September 2015, the Chinese government created two segments of SOEs: “Public Welfare Providers” and “Commercial SOEs”, raising questions about whether the latter segment would receive less extraordinary government support than anticipated by market participants – a huge change in local investors’ perception. Furthermore, the recent opening of the onshore market to international investors (they currently account for just 2%), albeit positive in the long term, is likely to bring greater credit differentiation across the onshore credit curve as new investors will have a broader benchmark universe and we could see the arrival of covenants in domestic bond documentation.

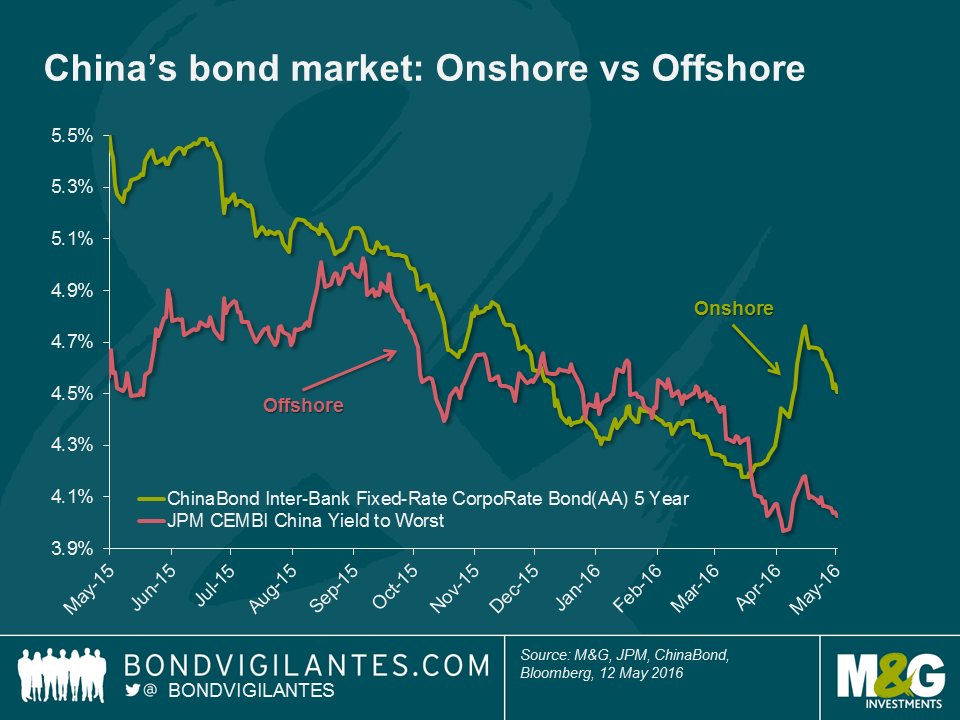

In theory, China’s softer economic environment and greater default risk should have pushed onshore bond market yields higher. The reality is quite the opposite. Corporate bond yields have declined materially in 2015 fuelled by rate cuts and private bank incremental bond buying after the stock market collapse. This decoupling of fundamentals relative to valuations was similarly observed in yields for US dollar-denominated bonds issued by Chinese corporates which, over the course of 2015, performed extremely well thanks to supportive market technicals, and despite deteriorating fundamentals (i.e. softer macroeconomics, asset quality deterioration for banks, oversupply and lower growth rates for property developers, higher leverage of a number of SOEs, etc.).

The attractive cost of funding in renminbi has been a positive technical backdrop for China’s offshore corporate bond market, which includes a large number of property developers. These issuers took advantage of the low yield and surprisingly high rating of the onshore market to refinance their US dollar bonds – enabling them to reduce FX mismatches on their balance sheets. For instance, in 2015 Chinese real estate developer Evergrande issued a CNY 5 billion onshore bond with a yield of 5.38%, which was locally rated AAA by the Chinese rating agency Dagong. Evergrande’s US dollar bonds (yielding above 8% for shorter maturities) are currently rated B3 and CCC+ by Moody’s and S&P, respectively. It is therefore easy to understand why property developers rushed on the onshore bond market for funding. As a result, the supply of US dollar bonds issued by Chinese corporates diminished whilst, in parallel, local investor demand for US dollar bonds remained high due to RMB bearishness and poorly performing equity markets.

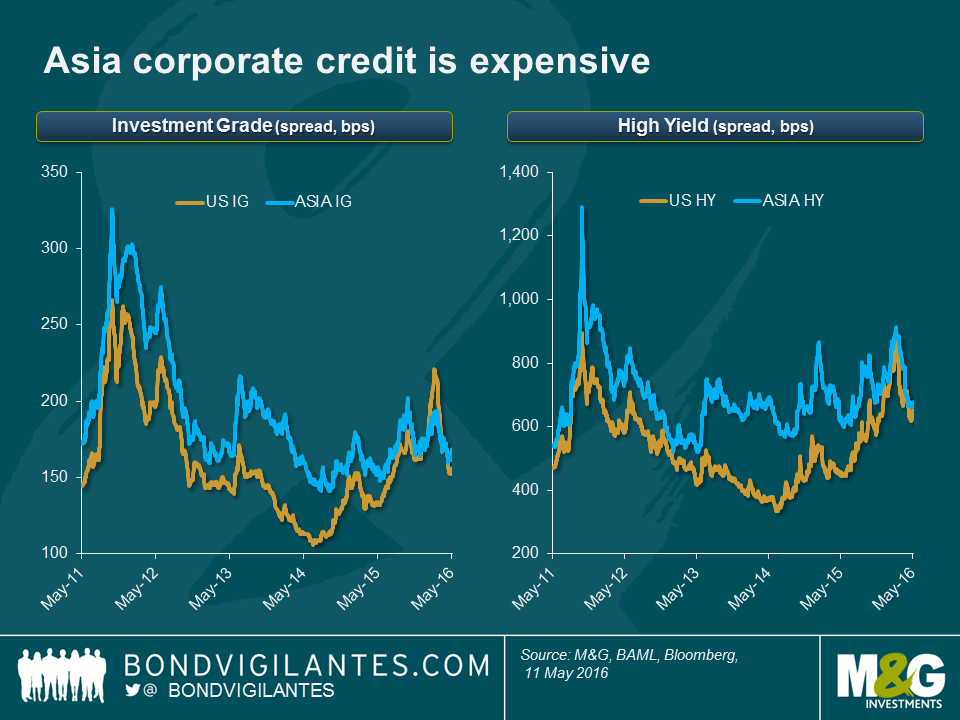

From a global investor’s perspective, this has resulted in a quite unattractive valuation point for offshore bonds. First, emerging markets bond investors may find higher bond yields outside of China, offering both a carry play and capital appreciation upside on credits with strong fundamentals – especially those that were unduly punished by the negative sentiment towards the asset class as a whole. Second, the repricing of corporate bonds in developed markets, notably in the US, makes Chinese US dollar bonds very expensive, especially bearing in mind the subordination risk (to domestic bonds) born by offshore investors in China. The following chart provides good evidence of tight valuations in Asia (of which a large share is China) versus US investment grade and high yield credits.

If China’s onshore default rates continue to increase at the current pace – which is very likely – and we witness an expected rise in onshore bond yields, there is a real risk of Chinese issuers turning down the onshore bond market to tap the offshore market. This would increase supply of US dollar bonds and put an end to the positive technical backdrop in terms of supply. Removing the technical aspect, fundamentals will catch up – as they always do – in the long run. On top of higher leverage resulting from a weaker macro, increased US dollar issuance will generate higher currency risk on balance sheet assuming some degree of depreciation of the RMB going forward. It will then only be a matter of time before the offshore bond market re-prices. The repricing should be uneven and US dollar high yield bonds would be most at risk with demand from local private banks and international investors turning to the better quality credits in a market where low yields no longer compensate for the greater default risk.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox