Are rating agencies overlooking the impact of COVID-19 on Eastern Europe and Central Asia?

Rating agencies’ drawbacks come to light again

In times of crisis, markets understandably pay particular attention to the actions of credit rating agencies. For example, during the global financial crisis of 2008-09, the rating agencies were widely accused of failing to identify the widespread vulnerabilities in the financial system, reacting with “behind-the-curve” blanket downgrades. The main shortcomings of the rating agencies are well-known: slow reaction to new events and data, use of complicated and non-transparent indicators that are difficult to track and making ad hoc adjustments to the final rating (often based on unsubstantiated opinion rather than hard data). Furthermore, changes between different rating levels seem to be subject to varying thresholds (e.g. it takes more to move between IG and HY than it does intra-IG or intra-HY). Finally, some countries are not rated by some rating agencies (e.g. Armenia is not rated by S&P, Montenegro is not rated by Fitch).

During the current pandemic, the rating agencies seem largely to have adopted a wait-and-see approach in parts of EM, avoiding any negative moves for as long as possible. While this could have been justified at the early stages of the pandemic due to huge uncertainties, almost a year later their actions for many countries across Eastern Europe and Central Asia hardly look justified at first glance. Importantly, for some countries they have ignored or contradicted their previous assessments.

Fiscal deterioration in EM to last for years

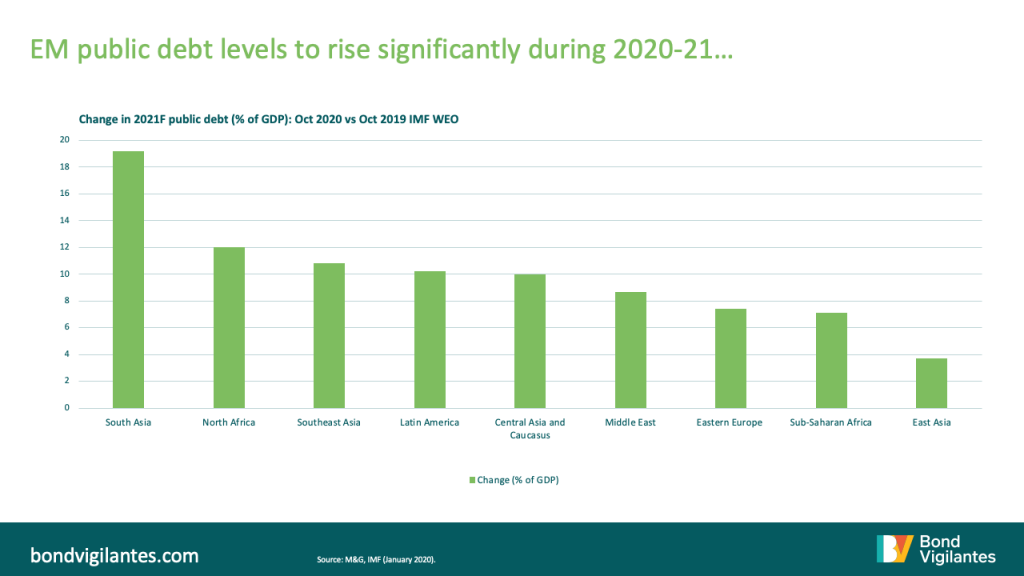

The impact of the pandemic on the macroeconomic variables determining a country’s willingness and ability to repay its public debt has been clearly varied. For example, the impact on GDP growth could be considered temporary in a multiannual framework of rating agencies’ views. Indeed, the vast majority of EM countries are expected to return to the path of solid growth in 2021 and recover to previous levels of output in 2022. The impact on fiscal policies and debt levels is likely to last for longer, however. In order to support economic growth in 2021 and beyond, many countries are willing only gradually to curb the huge fiscal deficit expansions seen in 2020. According to the latest IMF forecasts, this will push EM public debt on average about 9 percentage points (pp) of GDP higher this year compared to their pre-pandemic (October 2019) assessment for 2021. It is worth noting the significant variation across regions, with double-digit increases for South Asia and North Africa. Eastern Europe and Central Asia are no exceptions either, with public debt levels on average expected to be higher by 7-10pp in 2021. Importantly, in almost all countries the IMF expects this to be a permanent deterioration throughout its forecast horizon of 2025.

Preference for no reaction

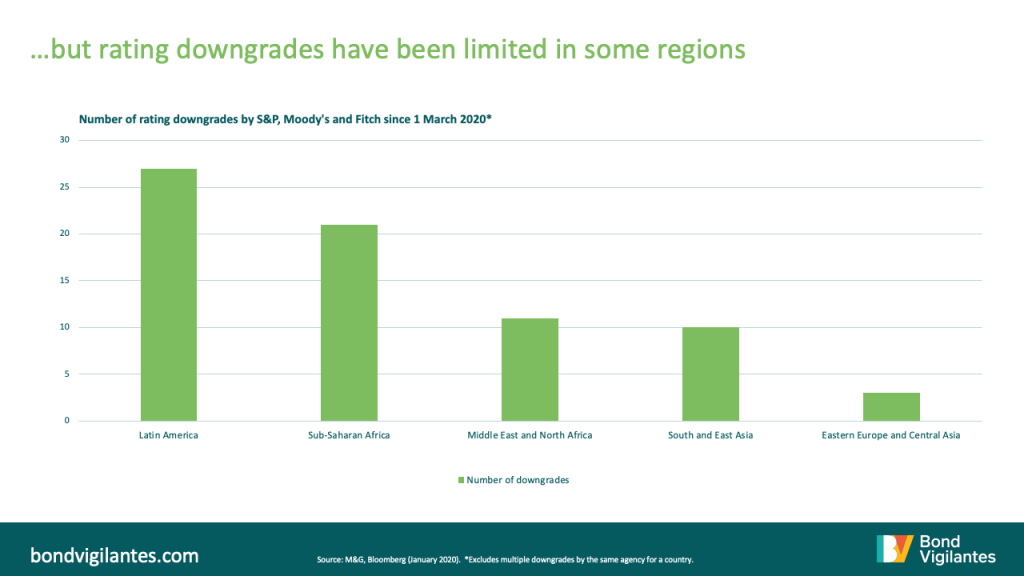

Since the start of the pandemic in February 2020, there have been more than 70 sovereign rating downgrades in EM. However, these have been distributed very unevenly, with the majority in Africa and Latin America. Meanwhile, in Eastern Europe and Central Asia the number of rating upgrades surprisingly exceeded that of rating downgrades. Out of 25 countries in the region, only Turkey, Armenia and Slovakia were downgraded. Croatia, Bulgaria, Ukraine and Slovenia were actually upgraded (all by Moody’s) in the middle of the pandemic despite significant long-term deterioration of public debt levels in all of them.

Given it’s been almost a year since the pandemic began, the argument that it takes more time for the rating agencies to react does not seem to hold. In fact, for the vast majority of countries across Eastern Europe and Central Asia the rating agencies did not even revise lower their rating outlooks (or downgrade where they had been negative already) despite the much-worsened longer-term forecasts. Romania was perhaps the most striking case, where a negative rating outlook assigned by S&P in December 2019 (i.e. well before the pandemic) miraculously did not lead to a rating downgrade in 2020. In its December 2019 rating assessment, S&P was concerned with the budget deficit increase from 3% to 4.5% of GDP in 2019, threatening a downgrade in case of further fiscal slippage. However, it failed to act when the deficit increased to 9% of GDP in 2020 and was projected at 7% in 2021.

Benefit of the doubt

It is interesting to try and understand the reasons behind the rating agencies’ surprising reluctance to take negative action (or even taking a positive one) in many cases. From a theoretical perspective, in determining a country’s credit rating it should not matter much whether a deterioration in its ability to repay debt was caused by external circumstances or the country’s own policies. However, it seems that during this crisis the rating agencies have been willing to overlook lasting deteriorations when they had confidence in the country’s future policy adjustment and general institutional strength. That would partially explain the significant number of downgrades and negative outlooks in Africa (full of low-income sovereigns with weak institutions) compared to Eastern Europe (where many sovereigns have high income and strong institutions by EM standards). For example, this argument applies to Croatia, whose entrance into the ERM 2 mechanism (the so-called “waiting room for the euro”) in mid-2020 proved to be much more important in securing a rating upgrade than the 15pp of GDP in public debt deterioration during 2020.

It would seem that the rating agencies preferred to give many countries the benefit of the doubt, perhaps to a larger extent than in previous years. For example, this seems to hold for Romania where, despite 8pp of GDP in public debt deterioration in 2020 alone, all three main rating agencies decided to avoid a long-awaited downgrade to junk, banking on the new government to change fiscal policies radically in 2021. Only time will tell whether they are right – most investors seem to disagree for now, continuing to price Romania’s debt at sub-IG spread levels.

Increased EU support has helped

Another factor specific to Eastern Europe has been the sheer scale of support from the EU in the form of grants and cheap loans (primarily via the new Recovery Fund). As a share of GDP, it has been much larger and longer-lasting compared to the crisis-related IMF and World Bank support to EM countries. In some EU countries, the associated increase in EU funds could amount to 3-4% of GDP per annum for the next four years, reducing the need for market borrowing in the future. While this financing is mostly tied to development projects (and thus will depend on a country’s absorption rate), its significant positive impact is clear. Some non-EU countries in the region will also receive additional support (albeit at much lower levels) via the Western Balkans and Macro-Financial Assistance programmes. The argument that debt increase matters less when financed with secured future grants and long-term low-interest official borrowing does seem to apply in these cases.

Do your own research

The rating agencies’ mixed reaction to the pandemic only further underscores the need for investors to perform their own analysis for EM countries, rather than blindly relying on someone else’s. With uncertainty still significant going forward, the rating agencies might run out of patience in 2021-22 if the anticipated policy adjustments across EM prove to be harder than expected. In the EM sovereign universe, it seems to be increasingly the case that the rating agencies just followed the markets, rather than vice versa.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox