How to transform a pair of guided nuclear missiles into a sperm whale and a bowl of petunias?

In The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy, a device known as the Infinite Improbability Drive, consisting of some complicated electronics suspended in a cup of hot tea, enabled instantaneous travel across the universe. At the point of reaching infinite improbability, it travels through every point of every universe simultaneously with some equally improbable side effects, including turning two incoming nuclear missiles into a sperm whale and a bowl of petunias, along with an interior makeover of the targeted spaceship.

Whilst yet to be confirmed, one has to wonder if President Trump’s top physicists have created their own Infinite Improbability Drive and installed it in the Oval Office to replace a broken fidget spinner. Certainly, events have been unusually unpredictable of late, and markets have struggled to make any sense of the pronouncements from the President and his top team. On April 8th, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said the President “has a spine of steel and will not break”. Perhaps unknown to her at that point was that 10-year US Treasuries had just opened 20 basis points weaker as she spoke. Within 24 hours, 10-year yields reached 4.50%, up from 3.90% merely 36 hours earlier. On April 9th, the President suspended most of his reciprocal tariffs for 90 days. It was the plan all along apparently. Shame he didn’t tell markets that from the start, as it would have saved a lot of bother, but then that’s the Art of the Deal.

At first blush, what was improbable about these market moves was that Wall Street analysts were falling over themselves to raise the probability of a tariff-induced recession. Influential JP Morgan CEO, Jamie Dimon, suggested that a recession is the “likely outcome”, and others chimed in alongside him. Against that backdrop, every drop of market experience over the past 30 years would have said that US Treasuries should be rallying, with yields falling precipitously, representing, as they do, the world’s premier safe haven asset. There would also be an expectation that the Federal Reserve Put1 would kick into operation and interest rate cuts would follow.

That the reverse happened, that yields rose rapidly, is widely seen as a sign that the difficulty in understanding the policy regime was rapidly undermining investors’ confidence in US assets as a destination for their capital (probably along with some hedge fund leverage that needed to be unwound). Trump acknowledged the bond market “was getting a little queasy” and that it had “had a moment” but he had now sorted it.

As of the time of writing, 10-year yields have stabilised, falling slightly to about 4.3%, though still well above where they were early last week. The S&P has bounced off its lows but is still over 10% lower than its level in late February. It remains the case that effective tariff rates are around 20% of all imports, the highest rate since the early 1930s and the era of Smoot-Hawley. It’s tricky to calculate the exact number as it will depend on the degree of import substitution and, of course, Trump might well suspend, remove or increase any of the remaining tariffs. This precise uncertainty will doubtless weigh on markets. It will also infect all other US policy, since it is now rational to attribute a non-trivial probability for any announced plan to be changed, cancelled or doubled down on. And one has to spare a thought for the US Federal Reserve and other global central banks; economic forecasting is a fraught business at the best of times, but if you have little to no idea what the government policy of the world’s largest economy is going to look like, you might as well ask Russell Grant2 for your growth and inflation forecasts as inputs into your large-scale general equilibrium macroeconomic model.

Where does that leave investors of long-term capital? The answer is written on the front cover of the fictional electronic guidebook, The Hitchhiker’s Guide To the Galaxy, in large friendly letters, “Don’t Panic”. This adage is not a sign of complacency, nor does it imply we know what comes next. On the contrary, it is because we know that we don’t know, that we can resist the temptation to panic. When considering how to approach moments of volatility, an investment process that anchors to valuations rather than the noise of news and speculation will, in our view, maximise the probability of long-term market outperformance.

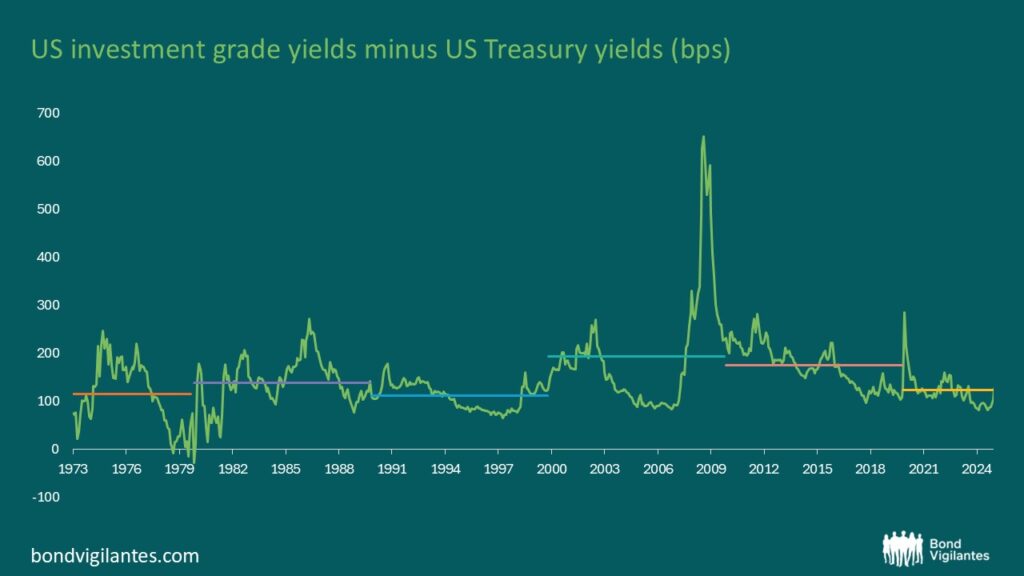

The latest market episode has rippled through to corporate bond markets, where we have been highlighting for some time that value is a little thin on the ground. Indeed, credit spreads, the additional yield for lending to a company rather than to the government, reached their tightest levels since the late 1990s around the end of 2024. A modest widening of spreads occurred in March as the first tariff-related sabre rattling got underway, but it’s been the past two weeks when this has accelerated. Setting this into an historic context is always helpful, and US data going back to the early 1970s gives us 50 years to pore over. In this chart of investment grade (IG) spreads, decade averages are marked and whilst phases of extreme distress like the 2009 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) or the risk-on irrational exuberance of the 1990s skew averages for those periods, the key observation is this: IG spreads much below a 100 basis points (bps) represent poor long-term value and, as sure as eggs are eggs, something we can’t foresee is going to come along and create a perturbation in the Force, offering a more attractive opportunity to buy.

Source: Bloomberg

From the tightest levels, US IG spreads are perhaps 50 bps higher. This broadly takes them back to the average since 2020, which importantly is similar to the averages of the 70s, 80s, and 90s. The 2000s are affected by the ’02 Enron et al episode and the GFC, and the 2010s represent a normalisation post-GFC. Two points follow: first, credit spreads have a helpful medium-term tendency to mean revert, and second, current levels are about average.

Averages can disguise sector dispersions and President Trump’s particular focus on the global auto industry, for example, has caused a particular pain point to develop for corporate bonds in that sector. The US High Yield auto index traded at 240 bps over government bonds at the end of February and widened to 440 bps by close of business on 11th April. Certain individual issuers did considerably worse than that, presenting opportunities to add a little exposure here and there.

It’s fair to say that liquidity last week was poor as markets absorbed the fallout from Liberation Day, and further, that there was no panic selling of credit flooding the market in the way it did during the GFC, so pickings for valuation-focused managers were modest. History suggests we will at some point be offered better odds than now, when spreads are firmly back above long-term averages. The infinite improbability coursing through markets right now may mean we see it sooner rather than later; certainly, the odds of something unusual happening has to have risen. Then again, an edgy calm may return for the time being, whilst markets wait for hard data on the economy and during which, we shift to the edge of our seats any time President Trump wanders out into the Rose Garden. For now ‘Don’t Panic’.

1 This is the notion, originally coined during the tenure of Chairman Greenspan, that the Federal Reserve will always intervene to support financial markets during a downturn.

2 Russell Grant is a British astrologer best known for horoscopes and television appearances.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.