The Art of the Tariff

Tariff headlines are designed to provoke and grab attention, with striking percentages quoted that appear to signal President Trump’s latest stance, framing the narrative around which country stands to win, and which to lose.

But the reality is far more nuanced than what a headline number suggests. Recently, we’ve seen that tariffs are driven not just by economic considerations, but increasingly by political motives

In this blog, I want to show why headline numbers can be misleading by highlighting the differences between two particular countries, Brazil and Vietnam, with both appearing to be on the opposite ends of the tariff spectrum. On paper, Brazil faces a 50% tariff on its exports to the US, while Vietnam faces just 20% after agreeing a trade deal with the US. By looking at headline numbers alone, you may be forgiven for concluding that Brazil’s economy is going to be worse hit than Vietnam’s, but once you dig into the finer details, and think about why these tariffs are in place, the conclusion is worlds apart.

When Trump first rolled out tariffs on Liberation Day, the logic was simple, albeit slightly misguided: target countries with big trade surpluses with the US i.e. target countries that exports more than it imports from the US. Based on this approach, Brazil faced the minimum 10% due to the fact they run a trade deficit with the US, whilst Vietnam received a level of 44% reflecting their large trade surplus with the US. So far so good. But in today’s environment, a mere four months post Liberation Day, the story is very different. This reversal reflects the changing scope of the tariffs from an economic tool, to a political tool designed to shape sovereign issues overseas.

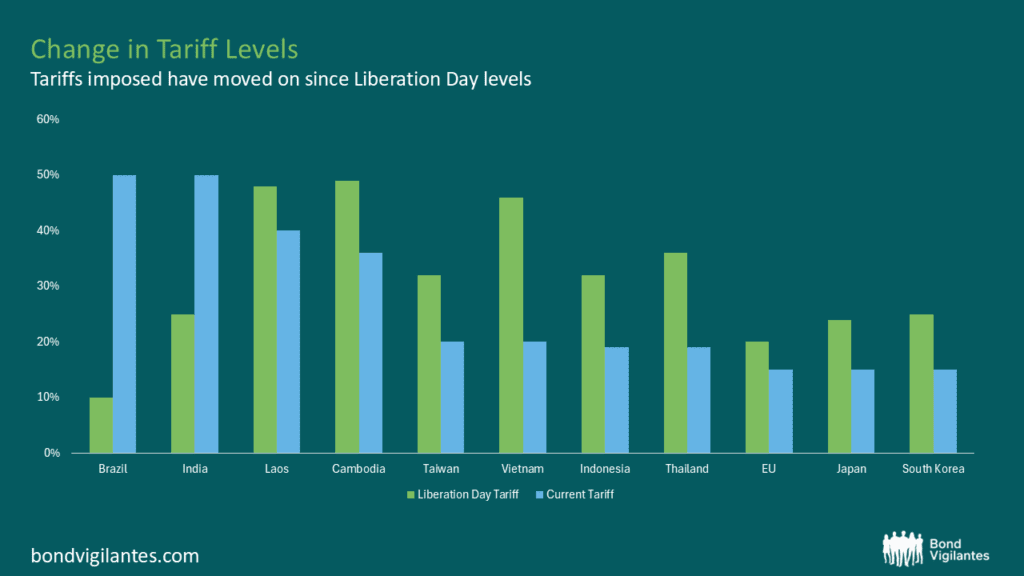

The table below provides some examples of how much tariff levels have changed between Liberation Day and now. We can see that Brazil and India stand out as having received increasing levels and we know that these have been politically driven. India for their continued purchase of Russian oil, and Brazil for reasons we will discuss a little later. For those that have seen decreases, the driver has been agreeing trade deals with the US administration.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg, as 12 August 2025. Stated tariff levels may vary across goods.

The more recent escalation for Brazil came after former president Jair Bolsonaro was indicted for allegedly plotting a coup d’état to overturn the 2022 election, which he lost to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

Prosecutors accused Bolsonaro and his allies of planning to nullify the election results with the charges being accepted by Brazil’s Supreme Court in early 2025, and the US response was swift: tariffs as a political weapon to support one of his closest allies in Bolsonaro. This isn’t new territory for Trump. He has long seen tariffs as a tool for leverage, but the speed and severity of this move underscores how far trade policy has drifted.

However, despite the headline-grabbing 50% tariff, the economic impact on Brazil is relatively muted. The US is not a major trading partner for Brazil, accounting for less than 10% of Brazil’s total exports. In fact, Brazil is one of the more closed-off economies when looking at major emerging markets. Moreover, most of Brazil’s high-value exports to the US, such as energy products, aircraft, and industrial materials, are exempt from the steep tariff and remain at 10%. The 50% rate mainly hits agricultural goods like coffee and beef, which, while symbolic, represent a smaller share of Brazil’s overall trade portfolio. And so, in practice, the tariff is more political theatre than it is an economic headwind for Brazil. And for this reason, it may be very unlikely to expect Lula to yield.

Vietnam, on the other hand, is far more exposed. The US is Vietnam’s single largest export market, absorbing roughly 30% of its total exports, primarily in electronics, textiles, and furniture. Even after the recent trade deal that capped tariffs at 20% (down from a threatened 44%), the hit is significant because Vietnam’s economy is deeply dependent on US demand. Add to that the complexity of transshipment rules, which impose 40% tariffs on goods suspected of being Chinese-origin, and compliance costs rise sharply. For Vietnam, this isn’t just a headline; it’s a structural challenge that will weigh on the economy.

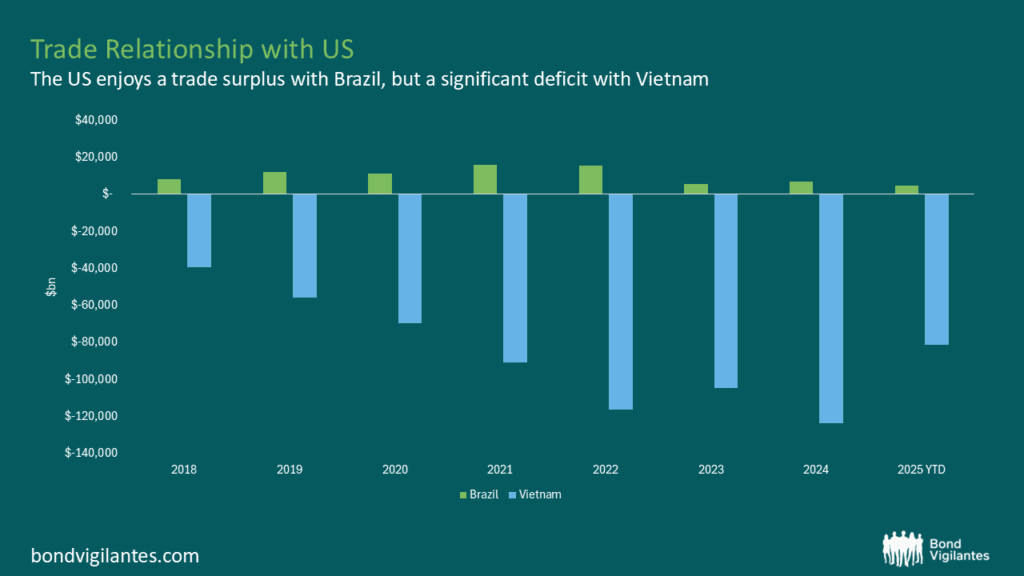

The vulnerability gap becomes even clearer when you look at trade balances. Since 2018, Vietnam’s surplus with the US has ballooned, a direct consequence of supply chains shifting during the US-China trade war in 2018-19. Brazil, by contrast, has maintained its steady deficit.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg, US Census as at 31 July 2025

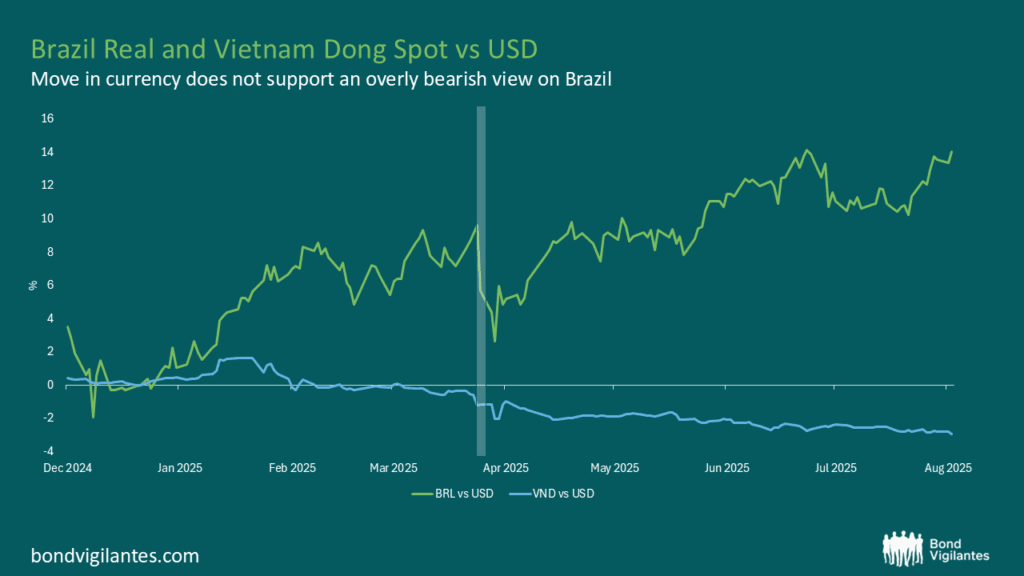

And in the face of these varying vulnerabilities, what are the markets telling us? The cost of buying insurance on Vietnamese and Brazilian debt has fallen year-to-date, but more so for Brazil. During the same period the Brazilian real has strengthened against the dollar by c.14.5%, while the Vietnamese dong has weakened c.3%. Now, currencies and credit spreads are influenced by a whole host of factors, so it would be wrong to claim these moves are entirely a direct reflection of tariffs. But markets are a good barometer of stress, and if there were genuine fears about Brazil’s economy after the tariff hike, we could expect to see it in FX or credit pricing… but we don’t.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg, as 12 August 2025. Shaded area denotes Liberation Day announcement.

And so what we can conclude is that whilst tariffs may dominate headlines, they rarely capture the full picture. Brazil and Vietnam offer an example of how the surface-level numbers obscure the economic impact. As we’ve seen, Brazil’s steep tariff hike is more about political signalling than economic punishment, while Vietnam’s seemingly lighter burden carries far heavier consequences due to its structural reliance on US trade. It would also seem that markets appear to understand this nuance better than the headlines do.

As we’re finding in today’s politically charged environment, whereby US trade policy is increasingly moving away from economic basis, it’s not enough to track the numbers, we need to understand the fine print that will determine the overall impact. Only then can we separate the noise from the signal.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.