Should Eurozone governments use their gold reserves to lower their borrowing costs?

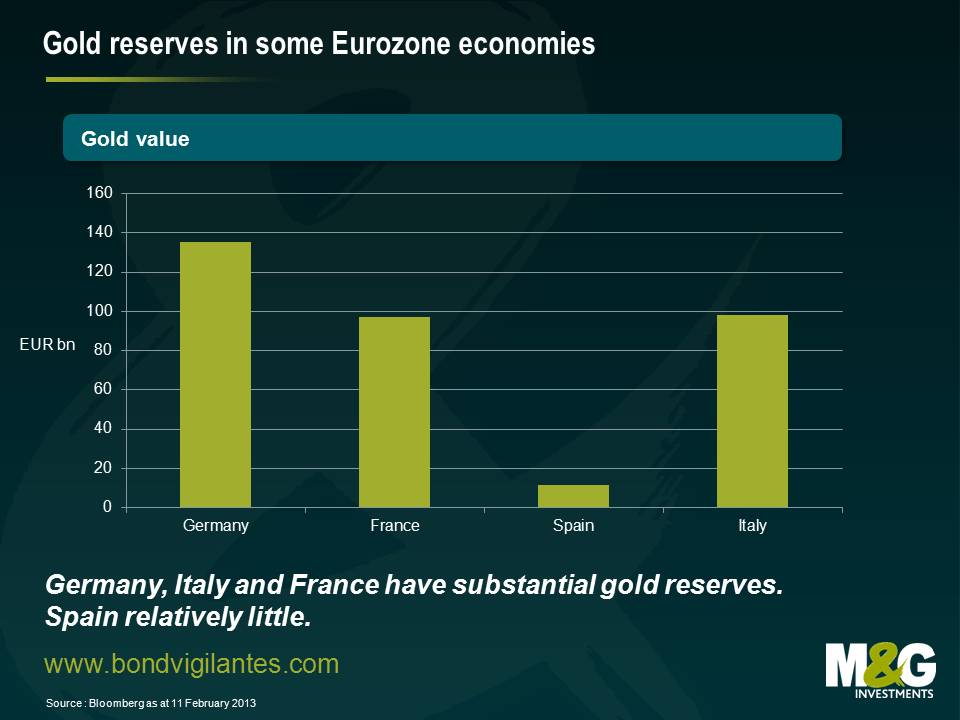

Last week we had Marcus Grubb of the World Gold Council come in to talk through the idea that Eurozone countries with high debt burdens and unsustainably high bond yields should unlock the value of their otherwise yieldless gold reserves by using it as collateral, and thereby borrow cheaply for at least that portion of their financing needs. The chart below shows that Germany (obviously one of the lowest yielding European members but here for interest), Italy, France and (to a much lesser extent) Spain have substantial gold reserves that could be used to collateralise European bond issuance.

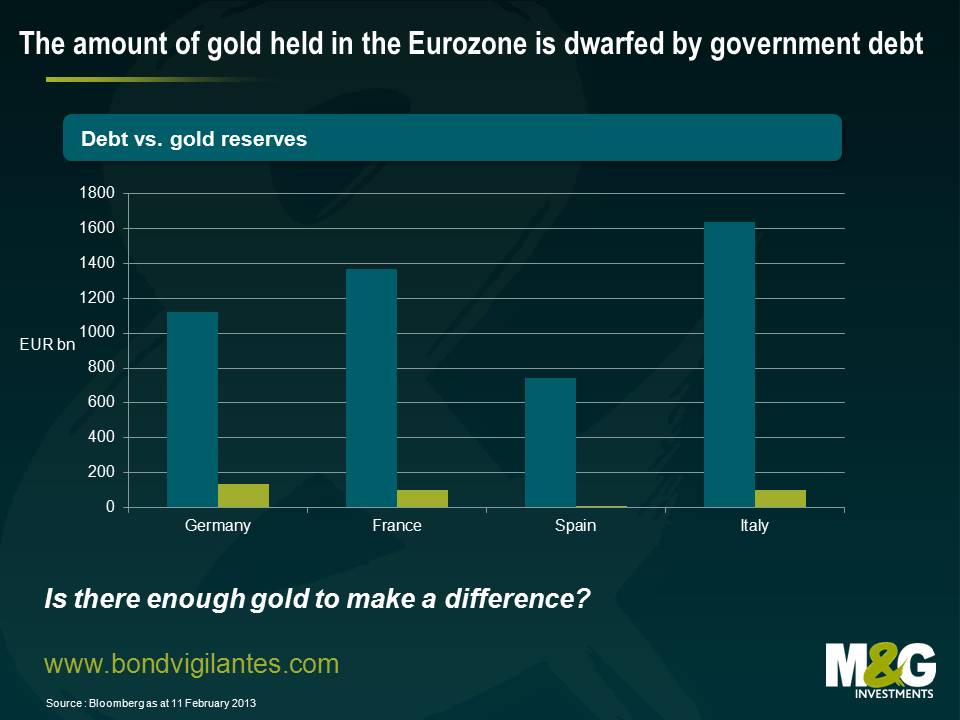

When we show gold holdings against outstanding levels of government debt we see that Germany has the equivalent of 12% of its debt in gold reserves (and incidentally as has been widely reported is repatriating 674 tonnes of its gold held by at the Banque de France and the New York Fed back to Frankfurt following a public campaign). For Spain though it’s under 2%. For France and Italy around 6-7%.

I think we can agree that issuing a bond backed by gold reserves would lead to lower borrowing costs – BUT only on that portion of the debt. This would effectively subordinate the pre-existing debt, and any future unbacked bonds. If the existing debt is effectively backed by the assets and tax gathering capabilities of the state, then to remove the gold reserves from these assets is reducing the creditworthiness of the outstanding bonds. Their yields should adjust upwards as a result. This is a bit like a bank subordinating senior bond investors by pledging its best mortgage assets to a covered bond programme – the covered bonds may be AAA rated, but the existing senior and sub bonds are jammed down the structure. Therefore, pledging gold assets as collateral might even lead to a ratings agency downgrade for some Eurozone countries – Italy is rated BBB at the moment, so could get downgraded to junk status if it pledges too many assets to a different bond programme. An unintended consequence. Nevertheless, there might be a combination of much lower gold backed bond yields (which might trade as AAA rated?) and higher existing bond yields that delivers an overall lower funding cost.

But how much scope would you have to issue this gold backed debt? To act as proper AAA collateral, the value of the gold asset at the maturity of the bond should be expected to cover the redemption amount, with a degree of over-collateralisation to cope with volatility in the price. You can see from the chart below though that in the past ten years the price of gold has been roughly between $400 and $1800 per ounce. If you took that as a possible range (and you might want it to be wider still), then what you see today as Euro 342 billion of gold reserves might only be able to collateralise Euro 76 billion of gold bonds – almost too small to be significant? At a lower confidence limit for the volatility of the gold you would be able to issue more bonds, but at higher yields.

What other objections might you have against the concept? Well does it seem a little desperate? Unconventional funding methods imply that all is not well (one of the reasons why under Paul Tucker, the Bank of England’s debt issuance department – before that responsibility went to the DMO – made great steps to modernise the gilt market, doing away with gilts with embedded optionality and quirks, and producing a transparent auction calendar). I think you’d want to get a highly rated issuer like Germany to issue a gold backed bond first, to establish a precedent, before the countries that might actually need to borrow like this did so. Secondly, since Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech, yields for Italy have fallen from 6% to 4.5% at 10 years, and in Spain from 7% to 5.5% – Open Mouth Policy without any real action has done far more for these countries’ borrowing costs than anything practical. Thirdly, having a claim on gold is not the same as having gold. To invest in such a bond you’d probably want the gold backing the instrument to be held outside of the country involved (and probably outside the Eurozone itself), for example in a custodian vault in Switzerland. Why would a country default on its debt but then send out truckloads of gold to bond investors around the world? My guess is that it would be disinclined to do so. Finally, our Central Bank Regime Change thesis suggests that the authorities will use their ability to create fiat money as a means of economic stimulus and (whisper it) debt reduction. A move towards gold, and its historical ties to the 1930s Depression, seems to be a move in the opposite direction to that desired.

So in summary, I don’t think that the Eurozone economies have enough of this shiny metal to make a difference to their funding costs, and given that, why do something that looks desperate that will cause angst for your existing bond investors and possibly raise your overall cost of funding if it goes down badly?

Incidentally, bonds backed by gold are not a new thing, although they have been out of fashion for a couple of decades. In Tom Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities (1987) Sherman McCoy is trying to buy $600 million of the French gold-linked Giscard bond, and it’s also discussed in Michael Lewis’s Liar’s Poker. The French issued four billion francs worth of gold indexed Rente Giscard bonds in 1973 – they were repayable in 1988 at either par, or 95.39 grams of gold for each 1000 franc note if the link between the franc and gold was severed in the lifetime of the bond, which it was. Sadly for the French government the gold price over the period (of high inflation) rose from around $100 per ounce to over $400 per ounce in the late 1980s. Thus the liability for the French rose to 53 billion francs. This was 1% of gross national product and 5% of government spending. This contemporary newspaper account suggests that the cost was £100 for every man, woman and child in France, and that were the debt to be settled in the metal itself it would equate to six months of global gold output. Some emerging market economies have used their gold reserves as collateral against loans before – South Africa engaged in gold swaps in the early 1980s for example. So the idea’s time might come again.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox