Is Europe (still) turning Japanese? A lesson from the 90’s

Seven years since the start of the financial crisis and it’s ever harder to dismiss the notion that Europe is turning Japanese.

Now this is far from a new comparison, and the suggestions made by many since 2008 that the developed world was on course to repeat Japan’s experience now appear wide of the mark (we’ve discussed our own view of the topic previously here and here). The substantial pick-up in growth in many developed economies, notably the US and UK, instead indicates that many are escaping their liquidity traps and finding their own paths, rather than blindly following Japan’s road to oblivion. Super-expansionary policy measures, it can be argued, have largely been successful.

Not so, though, in Europe, where Japan’s lesson doesn’t yet seem to have been taken on board. And here, the bond market is certainly taking the notion seriously. 10 year bund yields have collapsed from just shy of 2% at the turn of the year and the inflation market is pricing in a mere 1.4% inflation for the next 10 years; significantly below the ECB’s quantitative definition of price stability.

So just how reasonable is the comparison with Japan and what could fixed income investors expect if history repeats itself?

The prelude to the recent European experience wasn’t all that different to that of Japan in the late 1980s. Overly loose financial conditions resulted in a property boom, elevated stock markets and the usual fall from grace that typically follows. As is the case today in Europe, Japan was left with an over-sized and weakened banking system, and an over-indebted and aging population. Both Japan and Europe were either unable or unwilling to run countercyclical policies and found that the monetary transmission mechanism became impaired. Both also laboured under periods of strong currency appreciation – though the Japanese experience was the more extreme – and the constant reality of household and banking sector deleveraging. The failure to deal swiftly and decisively with its banking sector woes – unlike the example of the US – continues to limit lending to the wider Eurozone economy, much as was the case in Japan during the 1990s and beyond. And despite the fact that Japanese demographics may look much worse than Europe’s do today, back in the 1990s they were far more comparable to those in Europe currently.

Probably the most glaring difference in the two experiences is centred around the labour market response. Whereas Eurozone unemployment has risen substantially post crisis, the Japanese experience involved greater downward pressure on wages with relatively fewer job losses and a more significant downward impact on prices.

With such obvious similarities between the two positions, and whilst acknowledging some notable differences, it’s surely worthwhile looking at the Japanese bond market response.

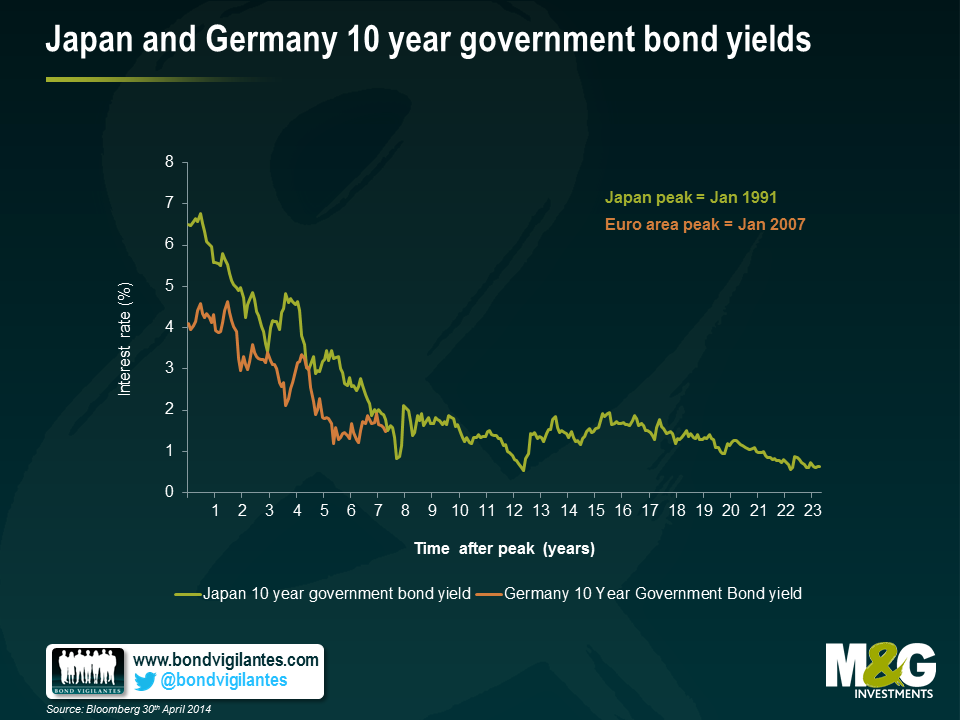

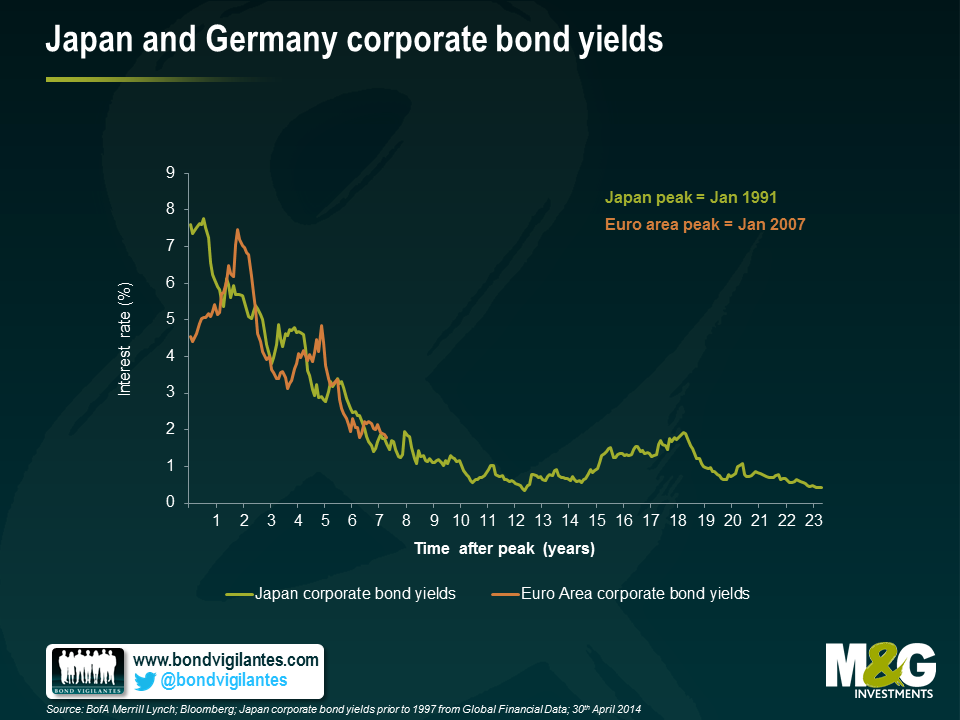

As you would expect from an economy mired in deflation, Japan’s experience over two decades has been characterised by extremely low bond yields (chart 1). Low government bond yields likely encouraged investors to chase yield and invest in corporate bonds, pushing spreads down (chart 2) and creating a virtuous circle that ensured low default rates and low bond yields – a situation that remains true some 23 years later.

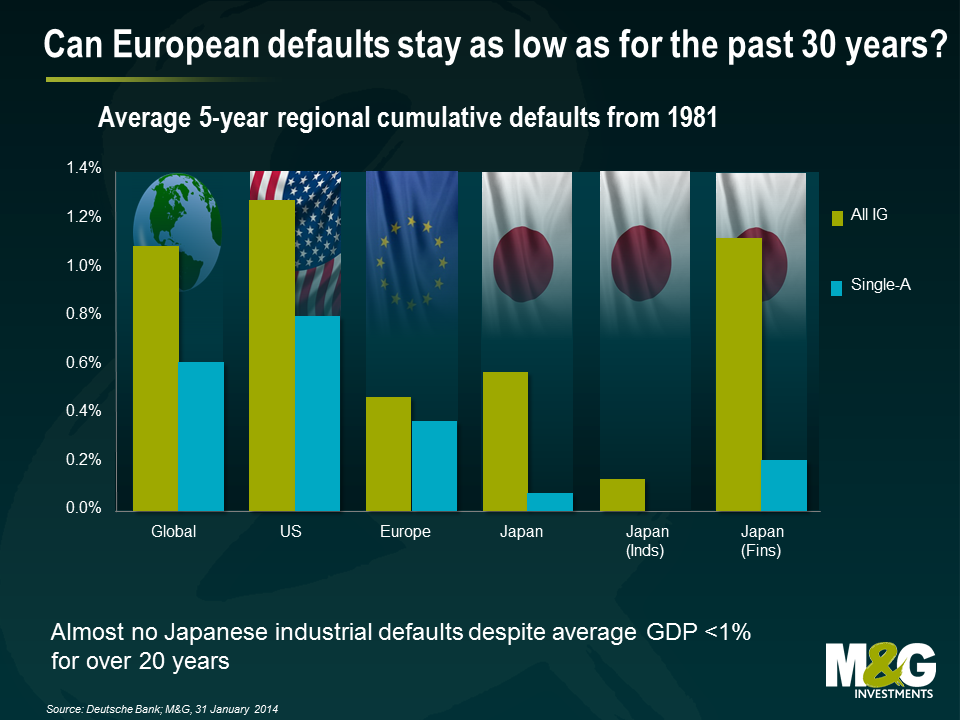

As an aside, Japanese default rates have remained exceptionally low, despite the country’s two decades of stagnation. Low interest rates, high levels of liquidity, and the refusal to allow any issuers to default or restructure created a country overrun by zombie banks and companies. This has resulted in lower productivity and so lower long-term growth potential – far from ideal, but not a bad thing in the short-to-medium term for a corporate bond investor. With this in mind, European credit spreads approaching historically tight levels, as seen today, can be easily justified.

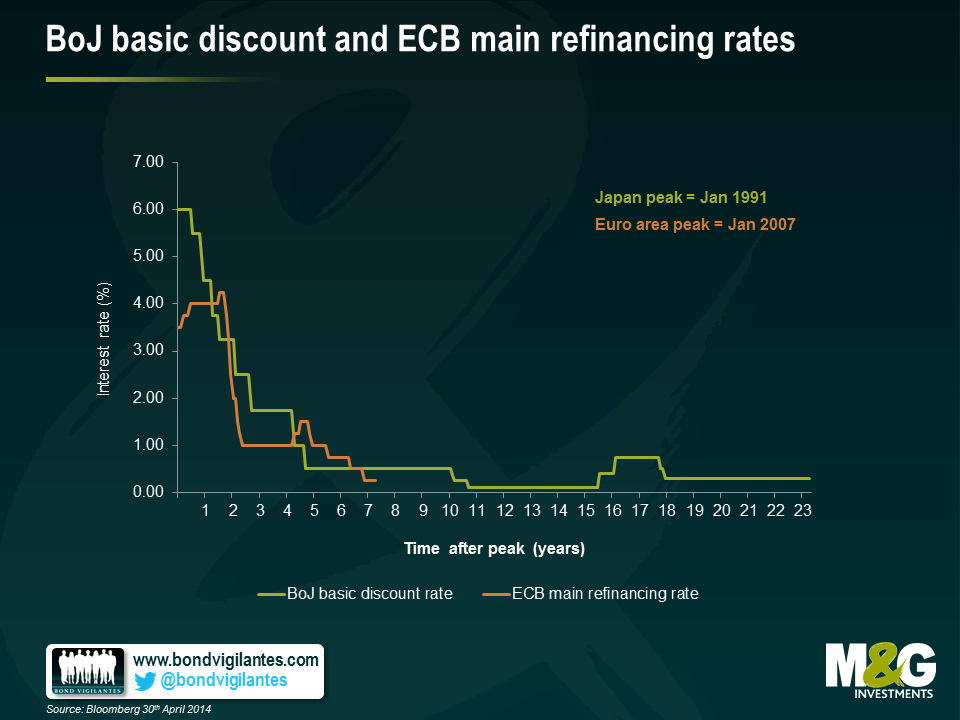

Europe currently finds itself in a similar position to that of Japan several years into its crisis. Outright deflation may seem some way off, although the risk of inflation expectations becoming unanchored clearly exists and has been much alluded to of late. Japan’s biggest mistake was likely the relative lack of action on the part of the BOJ. It will be interesting to see what, if any response, the ECB sees as appropriate on June 5th and in subsequent months.

Though it is probably too early to call for the ‘Japanification’ of Europe, a long-term policy of ECB supported liquidity, low bond yields and tight spreads doesn’t seem too farfetched. The ECB have said they are ready to act. They should be. The warning signs are there for all to see.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.