Bondfire of the Maturities: how to improve credit market liquidity

Liquidity in credit markets has been a hot topic in recent months. The Bank of England has warned about low volatility in financial markets leading to excessive reaching for yield, the FT suggested that the US authorities are considering exit fees for bond funds in case of a run on the asset class, and you’ve all seen the charts showing how assets in corporate bond funds have risen sharply just as Wall Street’s appetite for assigning capital to trade bonds has fallen. But why the worry about corporate bond market liquidity rather than that of equity markets? There are a couple of reasons. Firstly the corporate bond markets are incredibly fragmented, with companies issuing in multiple maturities, currencies and structures, unlike the stock markets where there are generally just one or two lines of shares per company. Secondly, stocks are traded on exchanges, and market makers have a commitment to buy and sell shares in all market conditions. No such commitment exists in the credit markets – after the new issue process you might see further offers or bids, but you might not – future liquidity can never be taken for granted.

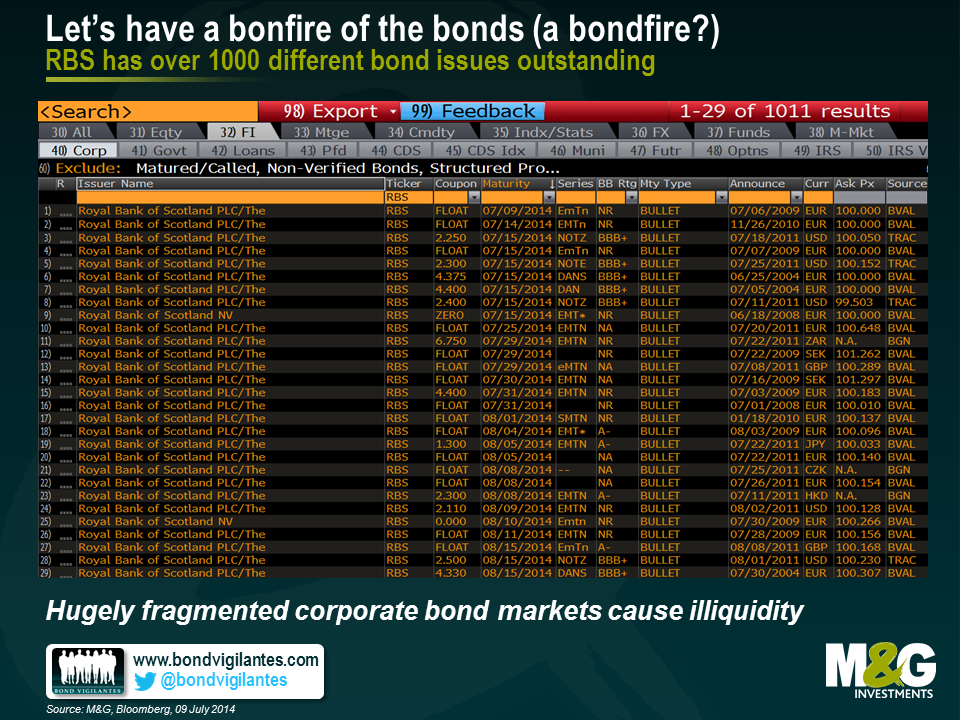

So how can we make liquidity in corporate bond and credit markets as good as that in equity markets? First of all let’s consider fragmentation. If I type RBS corp <Go> into Bloomberg there are 1011 results. That’s 1011 different RBS bonds still outstanding. It’s 19 pages of individual bonds, in currencies ranging from the Australian dollar to the South African rand. There are floating rate notes, fixed rate bonds with coupons ranging from below 1% to above 10%, maturities from now to infinity (perpetuals), inflation-linked bonds, bonds with callability (embedded options), and there are various seniorities in the capital structure (senior, lower tier 2, upper tier 2, tier 1, prefs). Some of these issues have virtually no bonds left outstanding and others are over a billion dollars in size. Each has a prospectus of hundreds of pages detailing the exact features, protections and risks of the instrument. Pity the poor RBS capital markets interns on 3am photocopying duty. The first way we can improve liquidity in bond markets is to have a bonfire of the bond issues. One corporate issuer, one equity, one bond.

How would this work? Well the only way that you could have a fully fungible, endlessly repeatable bond issue is to make it perpetual. The benchmark liquid bond for each corporate would have no redemption date. If a company wanted to increase its debt burden it would issue more of the same bond, and if it wanted to retire debt it would do exactly the same as it might do with its equity capital base – make an announcement to the market that it is doing a buyback and acquire and cancel those bonds that it purchases in the open market.

What about the coupon? Well you could decide that all bonds would have, say, a 5% coupon, although that would lead to long periods where bonds are priced significantly away from par (100) if the prevailing yields were in a high or low interest rate environment. But you see the problems that this causes in the bond futures market where there is a sporadic need to change the notional coupon on the future to reflect the changing rate environment. So, for this reason – and for a purpose I’ll come on to in a while – all of these new perpetual bonds will pay a floating rate of interest. They’ll be perpetual Floating Rate Notes (FRNs). And unlike the current FRN market where each bond pays, say Libor or Euribor plus a margin (occasionally minus a margin for extremely strong issuers), all bonds would pay Libor or Euribor flat. With all corporate bonds having exactly the same (non) maturity and paying exactly the same coupon, ranking perceived creditworthiness becomes a piece of cake – the price tells you everything. Weak high yield issues would trade well below par, AAA supranationals like the World Bank, above it.

So your immediate objection is likely to be this – what if I, the end investor, don’t want perpetual floating rate cashflows? Well you can add duration (interest rate risk) in the deeply liquid government bond markets or similarly liquid bond futures market, and with corporate bonds now themselves highly liquid, a sale of the instrument would create “redemption proceeds” for an investor to fund a liability. And the real beauty of the new instruments all paying floating rates is that they can be combined with the most liquid financial derivative markets in the world, the swaps market. An investor would be able to swap floating rate cashflows for fixed rate cashflows. This happens already on a significant scale at most asset managers. Creating bigger and deeper corporate bond markets would make this even more commonplace – the swaps markets would become even more important and liquid as the one perpetual FRN for each company is transformed into the currency and duration of the end investor’s requirement (or indeed the company itself can transform its funding requirements in the same way as many do already). Investors could even create inflation linked cashflows as that CPI swaps market deepened too.

So what are the problems and objections to all of this? Well loads I’m guessing, not least from paper mills, prospectus and tombstone manufacturers (the Perspex vanity bricks handed out to everyone who helped issue a new bond). But the huge increase in swapping activity will increase the need for collateral (cash, government bonds) in the system, as well as potentially increasing systemic risks as market complexity increases. Collateralisation and the move to exchanges should reduce those systemic risks. Another issue regards taxation – junky issuers will be selling their bonds at potentially big discounts to par. Tax authorities don’t like this very much (they see it as a way of avoiding income tax) and it means that investors would have to be able to account for that pull to par to be treated as income rather than capital gain. Finally I reluctantly concede there might have to be 2 separate bond issues for banks and financials. One reflecting senior risk, and one reflecting subordinated contingent capital risk (CoCos). But if we must do this, the authorities should create a standard structure here too, with a common capital trigger and conversion. Presently there are various levels for the capital triggers, and some bonds convert into equity whilst others wipe you out entirely. There is so much complexity that it is no wonder that a recent RBS survey of bond investors showed that 90% of them rate themselves as having a higher understanding of CoCos than the market.

Addressing the second difference between bonds and equities, the other requirement would be for the investment banks to move fully to exchange trading of credit, and to assume a market making requirement for those brokers who lead manage bond transactions. This doesn’t of course mean that bonds won’t fall in price if investors decide to sell en masse – but it does mean that there will always be a price. This greater liquidity should mean lower borrowing costs for companies, and less concern about a systemic credit crisis in the future.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox