Why have bonds sold off – and why did they even rally in the first place?

Ben Bernanke has spent a good deal of time explaining on his blog why he thinks interest rates are so low (something that Martin Wolf wrote a column on earlier this week). An extremely quick and dirty summary is low nominal interest rates and yields can be explained by low inflation, however this doesn’t explain why real interest rates are also low. Bernanke doesn’t think low real interest rates are down to Fed manipulation (if central banks had deliberately put rates too low then we’d have dramatically overheating economies when in reality we have the opposite) – it’s because the industrialised world generally is seeing weak growth, but in his view this probably isn’t to do with secular stagnation, it’s more to do with ongoing global imbalances.

As bond fund managers, we’re at least as interested in what drives longer dated bond yields versus what affects central bank interest rates and short dated yields. And short term and long term interest rates have been behaving wildly differently of late – market expectations for the first US rate hike have been broadly stable since the beginning of 2014, and yet 10 year US Treasury yields plummeted from 3% in January 2014 to almost 1.6% earlier this year, and have now backed up to 2.2%. As Bernanke explains, it’s all to do with what has been going on with the term premium.

Long dated Treasury yields can be split into three components – expected inflation, expectations about the future path of real short term interest rates, and a term premium, where the term premium is the extra return that investors require to own a long dated bond rather than investing in a series of short dated bonds. You’d normally expect the term premium to be positive since investors should require extra yield to compensate them for the risk of owning longer dated bonds (eg unexpected moves in inflation or the wider economy, uncertainty regarding the future path of central bank interest rates). However, the term premium collapsed through last year and various measures show it to have been outright negative for the first few months of 2015. Indeed, according to the New York Fed’s ACM model*, the rally in US Treasuries in 2014 was entirely due to the collapse in the term premium, and were it not for the collapse in the term premium, in December 2014 the 10 year US Treasury yield would have hit the highest level since 2008. And were it not for the recent jump higher in the term premium since February, US Treasury yields would not have sold off in the last three months but would have rallied!

So the very big, obvious question, is what drives the term premium? Historically the most important factor has been inflation and the perceived risk of unexpected inflation, and a low term premium today suggests investors see little risk of this occurring. The term premium tends to be counter cyclical, being higher in recessions and when there is macroeconomic volatility generally, perhaps because investors are highly uncertain about the direction of future Fed policy.

On the demand side, there’s evidence that the term premium drops if there’s a flight-to-safety bid, eg Russia default and Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) crisis in 1998 (although the term premium actually spiked sharply immediately post the Global Financial Crisis). Meanwhile the Fed’s QE program probably reduced the term premium, as have regulatory changes that encourage banks, brokers, insurers or pension funds to own more bonds.

And supply factors have also played a part – Greenspan’s ‘conundrum’, where a drop in the term premium meant that 10 year yields fell despite the Fed pushing short rates higher, can be partly explained by US Treasury issuance being heavily biased to short dated bonds from 2001-2006 (although large overseas purchases of US Treasuries likely contributed to a lower term premium – the savings glut – plus surely the predictability of the Fed’s policy contributed to the lower term premium given that they hiked rates by 0.25% in 17 consecutive meetings).

What has stumped Bernanke, along with many investors, was the collapse in the term premium through 2014, at a time when US economic data was robust, QE purchases wound down, and uncertainty and risk aversion were little changed. His two possible explanations are that economic weakness outside the US, and subsequent overseas central bank action, may have spilt over into US Treasuries. Oil prices also fell sharply about the same time as the term premium, but he doesn’t find either of these explanations ‘completely satisfying’ (implying not very satisfying at all).

In contrast, I’d argue that the overseas dynamic has been a key driver of the collapse in the US term premium.

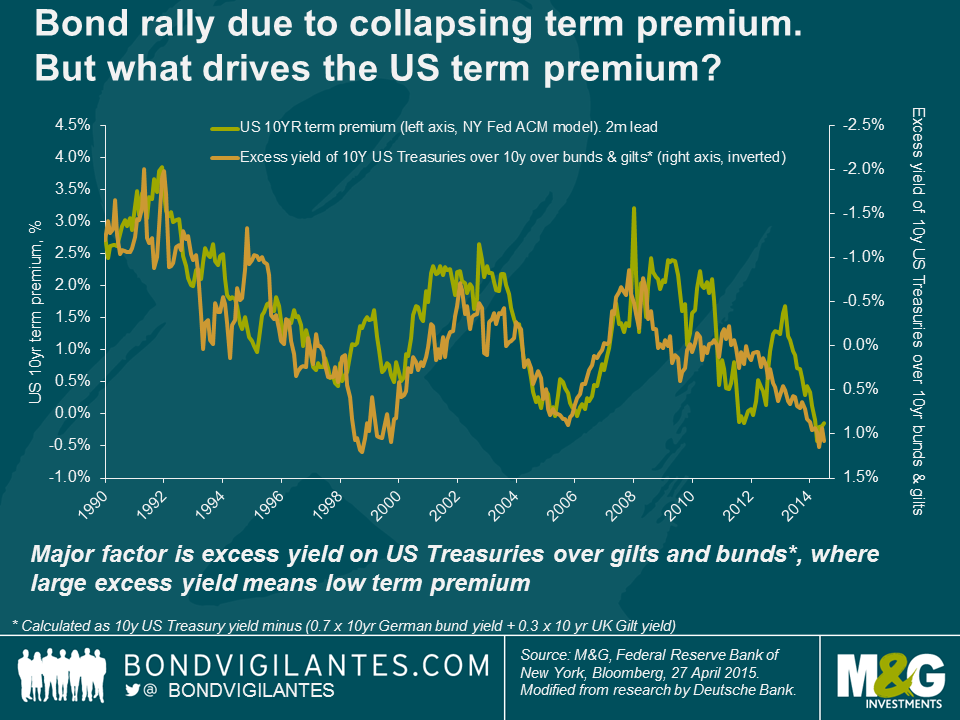

First, the chart below shows that over the last quarter of a century, higher yields in the US relative to German and the UK appear to cause a reduction in the US term premium ,and vice versa. One explanation for this is that higher long dated US bond yields, which are due to expectations of higher Fed funds rate (perhaps due to the relative economic strength of the US) encourage portfolio flows into US Treasuries from abroad, and these flows drive down the US term premium. Lower yields in the US have the opposite effect.

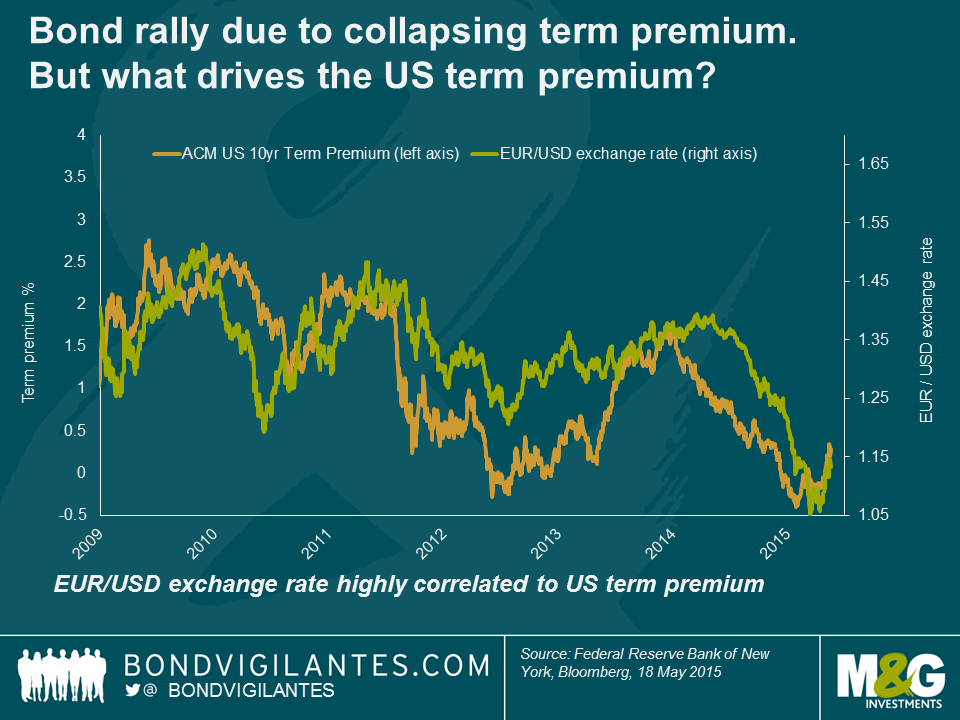

This explanation gains credence if you consider the reasonably close correlation between the US term premium and the EUR/USD exchange rate since 2009 in the chart below. This is related to the point above, given that differentials in short dated bond yields tend to be a major driver of FX movements, but it does suggest that the diverging economic fortunes and diverging actions between the Fed and the ECB has had a major impact on the US term premium on a 10 year US Treasury.

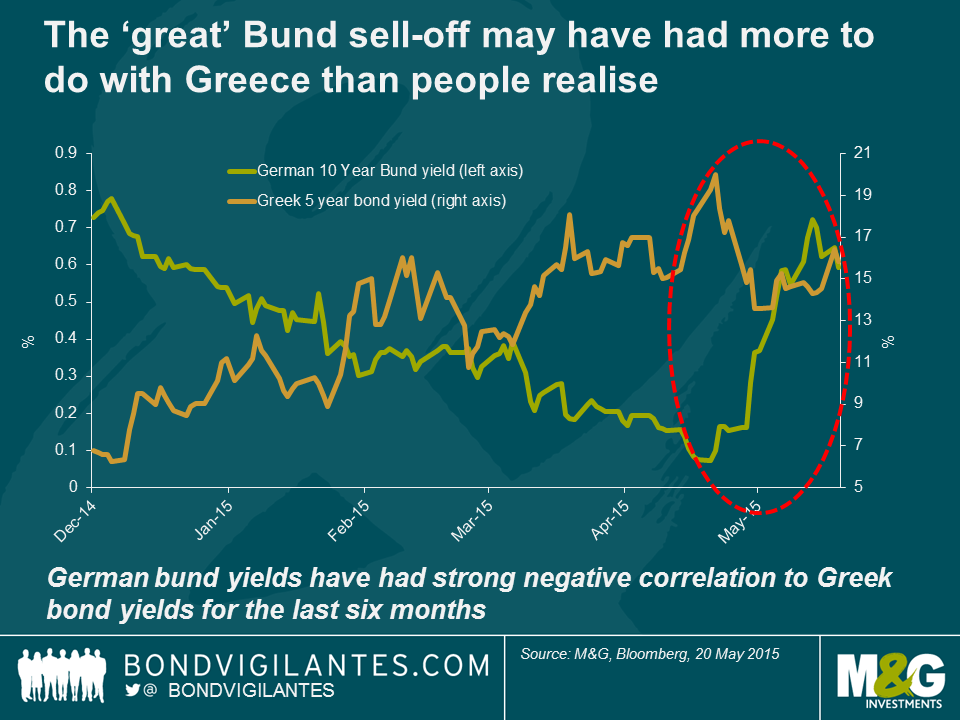

Focusing on just the past few months, the global bond sell off has surprised many given that US economic data has been consistently woeful. As already mentioned, this sell off can be entirely accounted for by the recent rise in the term premium. Again, I would argue that Europe has probably played a key role. European government bonds had already enjoyed a strong rally through 2014 on the back of sustained weakness in Eurozone economic data and expectations of ECB QE, expectations that were eventually validated. However the flaring up of the situation in Greece in October, and particularly since December, appears to have resulted in a significant safe haven bid for core Eurozone government bonds as suggested by the strong negative correlation between bund yields and Greek bond yields.

What are the implications of all of this? The main takeaway is that there are a number of factors that can drive the US term premium up or down, and previous studies have highlighted the correlation of term premia across markets, but Europe and the ECB seem to have recently played a key role. Just as exceptional US monetary policy measures up to last year were exported abroad (especially to emerging markets), the loosening of ECB monetary policy (and to a lesser extent Japan) is now being imported into the US.

So the implication for the investor is that longer dated US bond yields have, at least recently, had little to do with US specific factors. The behaviour of Eurozone bond yields has not been all about QE – crowded positioning may have exacerbated the recent bund sell off, but Greece has likely been a bigger driver of term premia globally in the past six months than many realise. The implication for the Fed is that the US is far from being in complete control of its own monetary policy, bearing in mind that monetary policy does not just include short term interest rates (led by the Fed Funds rate), but also the long term interest rate (Matt wrote a blog on an excellent BIS paper on this in 2013). If global factors are pulling US long term interest rates too low, resulting in excess stimulation of the economy (the most obvious feed through is via the housing market) then the Fed needs to take action. Either it needs to talk up long term rates , and Janet Yellen seems to have tried to do precisely this a few weeks ago (yesterday’s FOMC minutes also mentioned the term premium). Or if that doesn’t work, and it probably won’t if the term premium is indeed dominated by global factors, then it’ll probably need to hike short rates more aggressively than it otherwise would need to. Alternatively, if US data improves and it really wants to engineer a jump in the term premium, then the Fed can hint that it will look to sell back its stock of US Treasuries, which is something that Richard wrote about recently on this blog.

*The term premium is not directly observable, and there are multiple definitions and models that attempt to describe and model the term premium. The Kim- Wright model of the term premium, another widely used model, gives broadly similar results to ACM, although BIS use a model giving a considerably lower level of -2% in early 2015, albeit the general trend has been similar.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox