Long term interest rates – the neglected tool in the monetary policy toolbox

I was recently fortunate enough to see a presentation by Phillip Turner from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) on a paper he published earlier this year. ‘Benign neglect of the long term interest rate’ is a highly informative and interesting piece. In it he argues that after decades of the market determining long term interest rates the “large scale purchases of government bonds have made the long term interest rate key in the monetary policy debate”, and that a policy framework should be implemented around long term rates.

The use of central bank balance sheets isn’t as novel a concept as one might think when they hear (as I did repeatedly over 4 days of conferences and seminars in conjunction with the IMF/world bank annual meetings) QE described as unconventional monetary policy. In fact Keynes argued that central banks should stand ready to buy and sell government bonds as a means of affecting the price of money (the interest rate) from as early as the 1930s. Furthermore, the Thatcher government engaged in “quantitative tightening” as recently as the early 1980s by issuing more long dated gilts than were required to finance government spending. The rationale was that issuing more gilts would drain liquidity, curtail broad money growth and slow inflation more effectively than just increasing the Bank Rate.

Setting policy for longer term interest rates may be new territory for today’s generation of policy makers however it shouldn’t be for some. It’s often forgotten that the Fed actually has a triple, not dual mandate. Along with maximising employment and promoting stable prices they are also charged with providing moderate long term interest rates.

What constitutes a moderate long term interest rate is a matter for debate but the paper makes clear that adjusting the short term rate is not necessarily an effective measure in influencing the 10yr yield.

Turner argues that it may be more efficient to alter the average maturity of the outstanding government bonds – those not held by the central bank – through open market operations. The BIS has calculated that shortening the average maturity by one year will lead to a 1% reduction in the yield on a 10 year note. Essentially the message is that the longer the average maturity of the outstanding debt the tighter the policy.

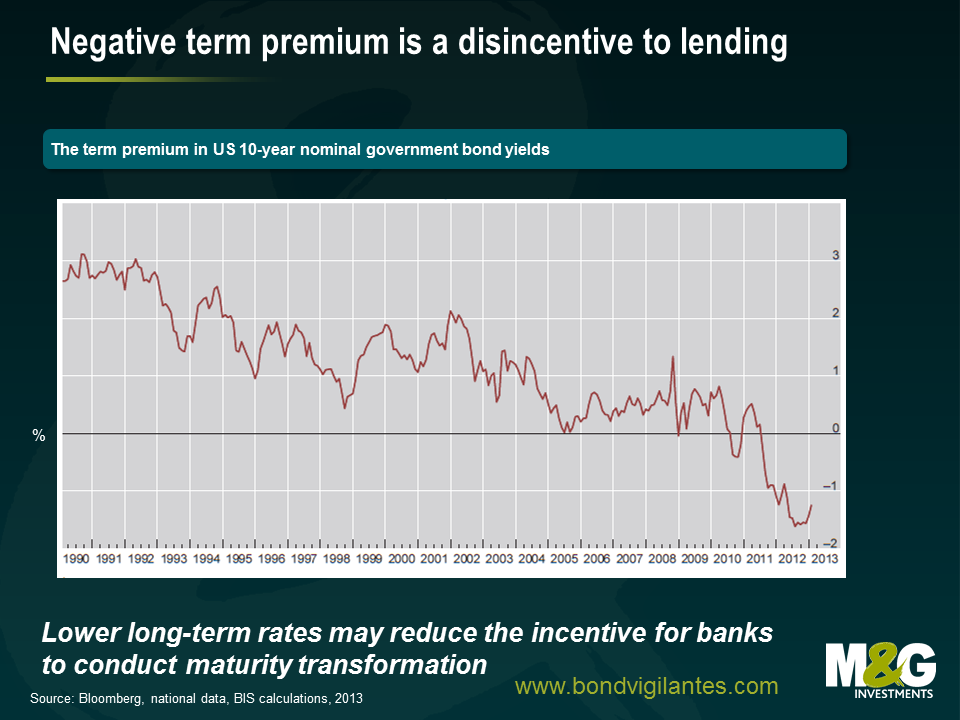

The inherent irony of lowering long term rates to stimulate the economy is that it reduces the incentives for banks to perform their socially useful function of maturity transformation – borrowing short and lending long. The lower long term interest rates the less of an incentive banks have to lend further out along the yield curve. The graph below shows that the term premium in the US 10yr has been negative for a large part of this decade.

However I believe that tougher regulation (larger capital buffers), increased litigation costs and a general de-levering of the economy will restrict the level of bank lending regardless of how steep the yield curve is.

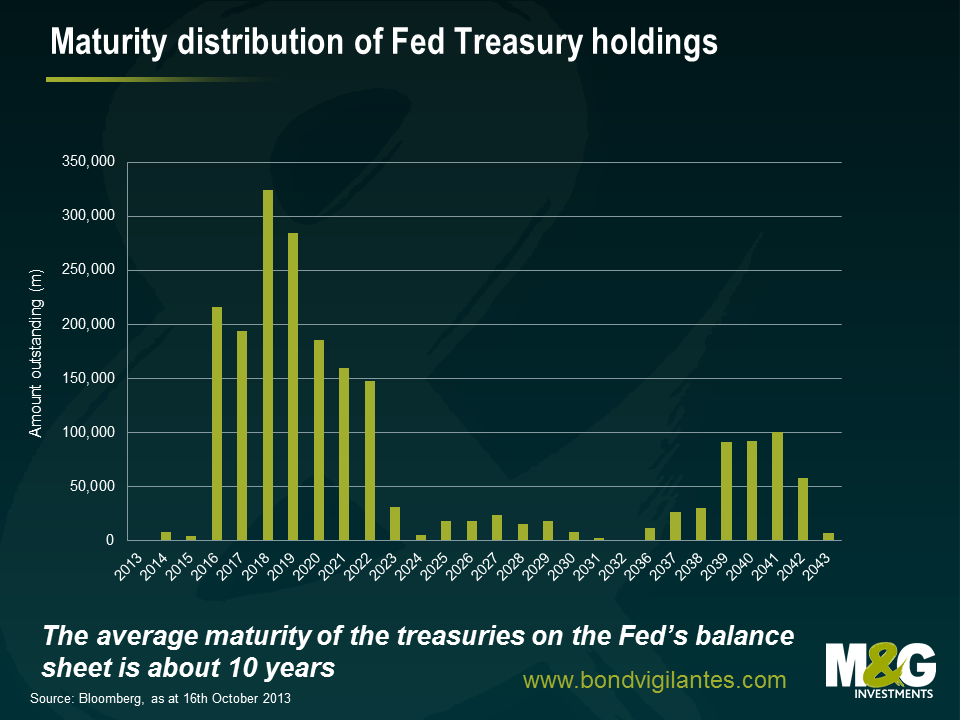

This chart shows the maturity distribution of bonds held by the Fed.

I’ve calculated that the average maturity of all Treasuries in issue is roughly 6 years, whilst the average of those on the Fed’s balance sheet is about 10 years. Operation Twist was a conscious effort by the fed to lower long run yields and they are still buying bonds at the long end. Given that factors other than the steepness of the yield curve are driving bank lending perhaps the Fed should be buying fewer Treasuries with 7-10 years to maturity in favour of even more longer dated ones. Also if and when they decide to sell their holdings they should consider this (and the on-going) analysis on the wider implications of altering the average maturity of the Treasury free float.

There are plenty of other interesting observations and questions raised in the paper so I recommend reading the whole thing…..especially if your job involves managing a central bank balance sheet.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

17 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox