Greek debt forgiveness: Where there’s a will, there’s a way

The Euro Summit meeting in Brussels that took place a couple of weeks ago seems to have finally provided some temporary closure to the Greek debt crisis. The dreaded Grexit scenario was avoided (at least for the moment) and the Greek government was able to repay its arrears to the IMF and the ECB using the €7.2 billion bridge loan provided by the European Council. Looking ahead, this short term loan gives Greece and its creditors a bit of breathing room to establish a “Memorandum of Understanding” around a more comprehensive bailout package, estimated to total approximately €85 billion over the next three years. In terms of concessions made by the Greek government, Prime Minister Tsipras was forced to cross many of his Party’s “red lines” on taxes and spending cuts, and these austerity measures will probably continue to exert pressure on the Greek economy for the coming months and years.

Whereas the lengthy negotiations until now have focused primarily on the reforms to be implemented by the Greek government, I find it quite interesting that very little progress has been achieved on providing some type of debt relief to the Greek government and its people. Indeed, despite having already been significantly reduced in 2012, Greek debt to GDP has soared again from less than 130% in 2009 to over 180% today, and according to the IMF should peak at 200% within the next two years. Even more alarmingly, debt dynamics in Greece continue to look extremely worrying, as continued slippage on the fiscal side and disappointing growth numbers (the European Commission recently reduced its growth forecast for Greece for 2015 from 2.5% to 0.5%) mean that the situation will continue to get worse before it gets better. More recently, the forced closure of the banks and imposition of capital controls only exacerbated the country’s woes, as a larger than anticipated capital injection in the Greek banking sector will now be required to keep it afloat.

Because of these recent developments, it now seems a widely accepted notion that the Greek government debt is unsustainable in its current form. This was not only mentioned fairly explicitly by the IMF in its update to its “preliminary draft debt sustainability analysis” (published last July 14th) but also by many people involved in the matter, such as the EU’s Economic and Financial Affairs Commissioner, Pierre Moscovici. The crucial and hotly debated issue now is whether relief on Greek debt should be provided via an upfront reduction in the amount of Greek debt (also known as a “haircut” or “debt forgiveness”) as requested by Tsipras and the Greek government, or through a debt restructuring (the preferred option for the Eurogroup led by Angela Merkel), which would keep the total value of the debt unchanged but would involve extending the maturities of the debt and lowering the interest costs.

Since the beginning of the crisis, Angela Merkel and her Eurozone partners have always said that debt forgiveness was out of the question for Greece, and this intransigence has caused them to receive quite a bit of criticism from international observers and from the Greek people themselves. To be fair, it is true that the idea of debt forgiveness does have some drawbacks:

- It would, for example, help fuel populist voices in other debtor countries, notably in Spain where the Podemos party would see its position strengthened.

- It would also have an immediate negative impact on the Greek banking sector, which still owns approximately €26 billion of Greek government bonds (although this represents less than 10% of total Greek debt) and would be forced to take further losses.

- The European Central Bank, who purchased over €20 billion in Greek bonds in 2010 through its Securities Market Program, would also be forced to realize losses, and the legal consequences of this are still uncertain.

- Finally, such a move, and this is Angela Merkel’s most voiced objection against debt forgiveness, would be impossible because it would go against article 125 of the Treaty of Lisbon (now known as the “no bailout clause”) that states that the Union shall not be liable or assume the commitments of other public entities.

Personally I find this argument to be a bit dubious coming from the same Angela Merkel who replied to David Cameron’s push for EU treaty reforms last 29th of May “where there’s a will, there’s a way”. Anecdotally, she repeated the same phrase to Tsipras on the 12th of June when negotiations were at a standstill, so she seems to be enjoying this expression at the moment. Nonetheless, the reality seems to be that the Lisbon Treaty can be amended for David Cameron’s reforms on European immigration and pensions, but not for Greece’s debt relief requirements.

I think this a shame because, despite the drawbacks, there are a couple of compelling arguments in favour of a haircut:

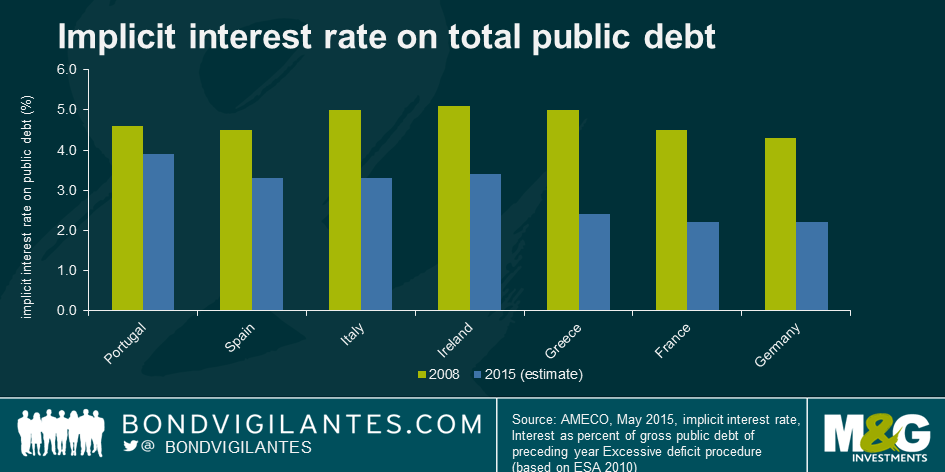

1. Given that Greek debt was already restructured first in 2010 and then again in 2012, the average interest rate that the Greek government currently pays on its debt is already quite low (around 2.4% according to the European Commission), only 0.2% higher than France’s and Germany’s, as the chart below shows:

In addition, the average maturity of the debt is also already quite long, at over 20 years. Because of this, not only would a restructuring only marginally reduce the cost of the debt, but also extend for several decades Greece’s financial tutorship and the need for austerity measures. For example, reducing the average interest rate on Greek debt from 2.4% to 1.4% and extending the average maturity of the debt by 30 years (as certain institutions have recommended), would only reduce the net present value of the debt burden by approximately 30%1. This would be a step in the right direction, but probably wouldn’t give Greece a whole lot of breathing room either.

And should interest rates be lowered and maturities extended for Greece, what will be the reaction of the populist parties in Europe? Surely their case for debt relief is almost just as strong whether that relief is provided via debt forgiveness or through a restructuring?

2. As we enter the 7th year of the Greek recession, one can argue that the country and its people have reached the end of what they can endure in terms of austerity measures. A Greek haircut would allow for some much needed increased spending in the short term, in view of boosting investment and reducing unemployment.

Hopefully, Germany and its Eurogroup partners are sensitive to the potential benefits of debt forgiveness, and have refused to consider this option so far because they believe the timing is not right. Indeed, with the upcoming national elections in Portugal,Spain and Ireland ,as well as the German federal elections in 2017, now is arguably not the best time to crystallise a loss on loans made to Greece.

In this respect, Germany’s strategy probably makes sense, and one can only hope that in a few years’ time –if Greece has demonstrated a strong commitment towards reforms and political pressures have abated in Europe– the idea of debt forgiveness may be back on the table. At this moment, maybe we will even hear Angela Merkel use her favourite catchphrase again… because where there’s a will, there’s a way… isn’t there, Mrs Merkel?

1 Assuming a flat discount rate of 2.4%

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox