What has the recent fall in oil prices got to do with inflation over the next three decades? Plus robots, charity, Morrissey.

First of all thanks to Business Insider. Every now and then we come into work to find hundreds of new Twitter followers have joined us overnight – this week it was thanks to BI listing us second in its round up of finance Tweeters. It’s a great list and pretty much everyone on it is worth a follow – I’d also recommend following Business Insider’s European markets editor Mike Bird (@Birdyword) if you are twittering-up.

Next, inflation. With energy directly representing 10-15% of CPI baskets in the developed economies, oil prices obviously have a significant feed through into headline inflation rates. The second round impacts are less visible, but transport costs in particular will be important in pretty much every other area of the inflation basket whether goods or services. In the US you expect the feed through from higher or lower oil prices to be more significant than in Europe – this is because Americans generally pay little tax on petrol at the pump, so changes in prices are much more direct than in the UK or Eurozone where the bulk of the pump price is fuel duty and VAT. In the UK for example, for a litre of unleaded petrol costing £1.10, roughly 58p is duty, and 18p is VAT, so the non-taxed element is around 30% of the pump price. As WTI and Brent crude oil prices have plummeted over the past year (Brent fell by 57% from August 2014 to August 2015), inflation has flirted with 0% at a headline level in the UK, US and Eurozone. Looking at recent Eurozone numbers, the energy component of the CPI fell by over 7% year on year. Despite the second round effects, all other major components were up (goods, food, and services – the latter up by 1.3% over the year).

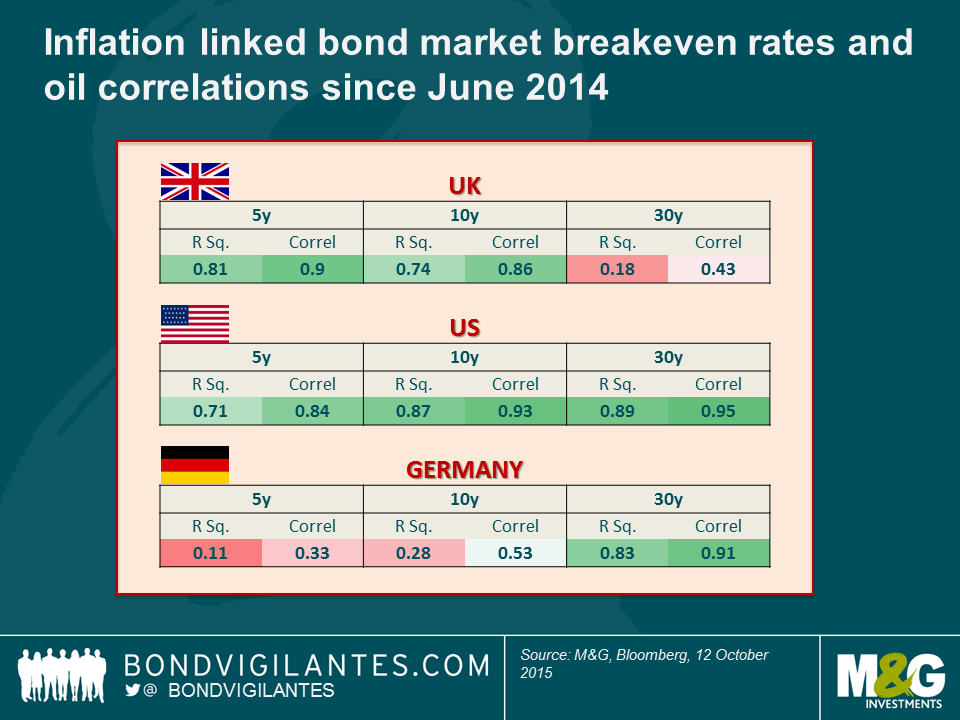

As these deflation fears rose, the price of inflation protection fell. Inflation linked bonds experienced a rocky summer, and the market measures of inflation expectations that policymakers follow closely – the 5 year breakeven rate expected in 5 years’ time – signalled danger. By the end of September, following the Fed’s talk of global slowdown as it held rates, the US TIPS market was expecting average headline CPI of just 1% on average for the next 5 years. Thinking about the next couple of years, a bear can make a good case for oil prices exercising downward pressure on inflation rates. There’s oversupply from US shale (and even those HY energy names that aren’t profitable below $50 per barrel still pump – any revenue is better than none, it’s their fixed costs and debt service that’s problematic, not marginal costs), and after years of sanctions Iranian oil is about to hit global markets. With China and EM demand slowing too, you wouldn’t be surprised to see oil prices lower in a year’s time. If oil fell to $25 then you’d expect to see the energy component of CPI to see another 7-10% fall, keeping headline annual rates towards zero. So you could make a case for short term breakeven rates of inflation to justifiably be correlated with oil prices. What is harder to explain is why the oil price and 30 year breakeven inflation rates are so highly correlated.

The table above shows that there has been a very strong correlation between 5 year breakeven inflation rates and the oil price since the middle of 2014 in the US and the UK. So far so good. But intriguingly the correlation with 30 year breakeven inflation rates and the oil price in the US is HUGE. 95% with an R Squared of 0.89. This was the highest correlation we found anywhere in the developed inflation markets. Why should current levels of oil prices impact expectations for the next three decades of US CPI? To have the same annual impact on the US inflation rate next year, oil has to fall to $25. The next year it needs to half again to $12.50. Then to $6, to $3, to $1.50 etc etc. I think there is an argument that energy costs trend lower – we’ve written about developments in renewables, batteries and fusion nuclear power on this blog– but even in a scenario that all energy becomes free, that impact disappears from the CPI numbers a year later too. So in the US, 30 year breakevens have fallen from their long term average of 2.4% two years ago to 1.67% now as the oil price halved. I don’t think it makes sense for markets to say that US policymakers will be unable to hit their 2% inflation target over the next 30 years on the basis of a one year movement in energy prices. It looks irrational.

Whilst we are talking about inflation, I remember that some years ago the Bank of England discussed receiving tons of letters about the lack of fivers in cash machines and in general circulation, and made it a goal to get more five pound notes out into the wild. At the time, I thought this was a very disinflationary signal – the public demanded smaller denomination notes than were generally available. Well, the Central Bank of Ireland has announced that it is trying to do away with both the 1 and 2 cent coins, and introducing rounding up or down to the nearest 5 cents (we wrote about getting rid of 1 and two cent coins in 2012). This is the opposite of what the BoE was trying to achieve, and is a small sign that we perhaps shouldn’t be that worried about deflation in Ireland any time soon. 28 October is Rounding Day.

Robots. I recently went to a breakfast with “Rise of the Robots” author Martin Ford to discuss his thesis that whereas in the last long phase of human development, machinery and technology replaced tools, the next phase, happening right now, is seeing machines (robots) replace workers. I am not entirely sure how you make a distinction, and I’ve seen research that suggests that technology has always destroyed millions of jobs, but has simultaneously created more. Where he might have a point is that this wave of technology is replacing “middle class” and “white collar” jobs to an extent not seen before, and that this might be a double whammy in that not only are jobs hollowed out, but the great consuming class is left poorer – robots don’t buy stuff, and the reduction in overall demand will be very damaging for society. Martin points to US labour force growth being 2 million+ per year, and expects significant social problems if robots are shrinking the available jobs pool for us puny humans. Wealth accrues to the robot owners, and vast numbers of people will be unemployed. A “basic income” might be required to allow living standards to be maintained (and to allow us to keep buying stuff). Martin might be right about the US, with its strong demographics and growing work force. But what about us poor aging Europeans, let alone Japan, or China, where the one child policy bakes a demographic nightmare in the cake. The working-age share of the global population probably peaked in 2012, after four decades of growth. Might robots be entirely necessary to do the work for us whilst we sit in old peoples’ homes? Interesting book though.

Two other recent reads: “Fields of Fire” by James Webb, the best of the Vietnam war novels I think, and “Doing Good Better” by William MacAskill. MacAskill’s book probably deserves a blog of its own; the book focuses on the most effective ways to give to charity and raises both fascinating moral issues and concepts like “micromorts” (the amount of time that you will, on average, lose from your life by partaking in an activity like motorcycling or smoking). TL;DR – you can save a life for a donation of about $3000, maybe less. Give your money to the best organisations that distribute mosquito nets and anti-parasite medication.

A book I can’t face reading is the new Morrissey novel. His autobiography was ace, but the reviews for “List of the Lost” are so universally bad that I am leaving it on my shelf. I do have exciting Morrissey news however. I was present at the very first Morrissey solo gig at the Wolverhampton Civic Hall in December 1988 (watch it below), and at the end of September he played what he claims might be his last ever UK concert, in Hammersmith. Having failed to get on stage in 1988, I’m pleased to announce that I made it over the barriers during Suedehead last month. Reader – the man himself shook my hand.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox