Why seasonality in consumer prices matters for bond markets

Guest contributor – Jean-Paul Jaegers CFA (Senior Investment Strategist, Prudential Portfolio Management Group)

One asset class where seasonality matters hugely is inflation linked fixed income. This makes a lot of sense, as inflation is the underlying macro variable, and inflation by its nature is very seasonal. For example, post Halloween sales or Holiday packages tend to happen in regular periods. As a result, seasonality becomes predictive and obfuscates the underlying trend. Therefore, institutions like statistics bureaus publish seasonally adjusted series for consumer prices (CPI).

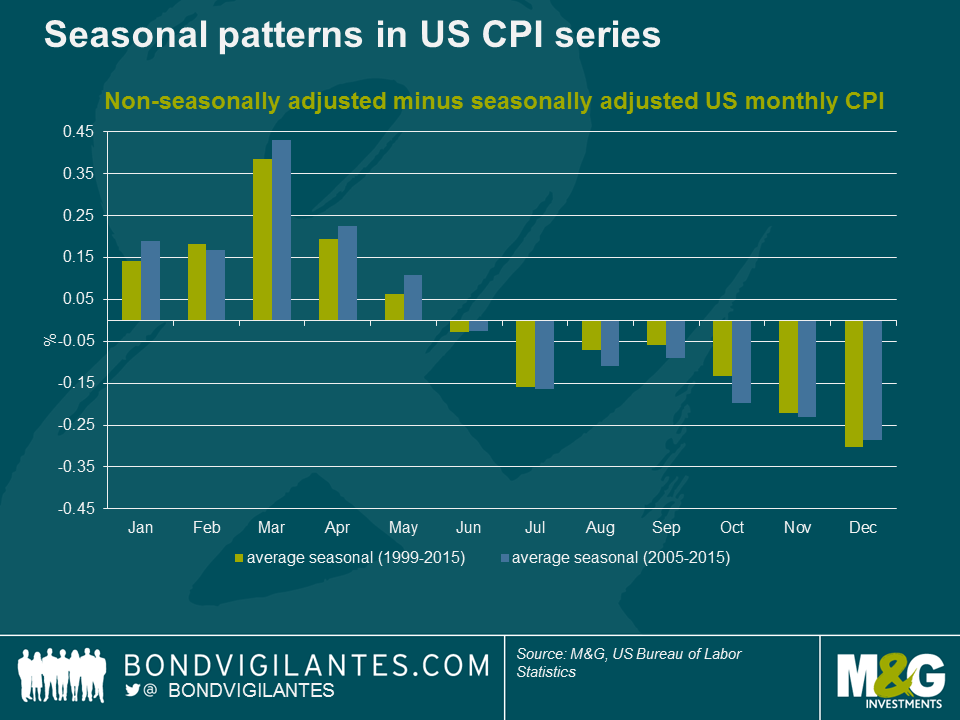

When we compare seasonally adjusted and non-seasonally adjusted CPI series published by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics and look at the average seasonal factor they have applied over the past 10 and 15 years, we see a pattern as shown in the chart below. In the first half of the year consumer prices tend to rise, whereas in the second half of the year consumer prices tend to fall. This is a very persistent pattern.

It is one thing to observe a pattern in macro variables, but the more crucial element is whether it matters for financial markets. Purely rational investors should anticipate seasonal patterns and therefore seasonality should be a non-profitable strategy. For example in inflation swaps, the forward curve includes seasonal factors, thus opening an inflation swap in December and closing this in June does not result in gains if inflation prints come in according to the normal seasonal pattern. For cash products this becomes a little bit more difficult as there is not a forward curve, there are lagged cash flows, and it requires arbitrage as there are two assets involved.

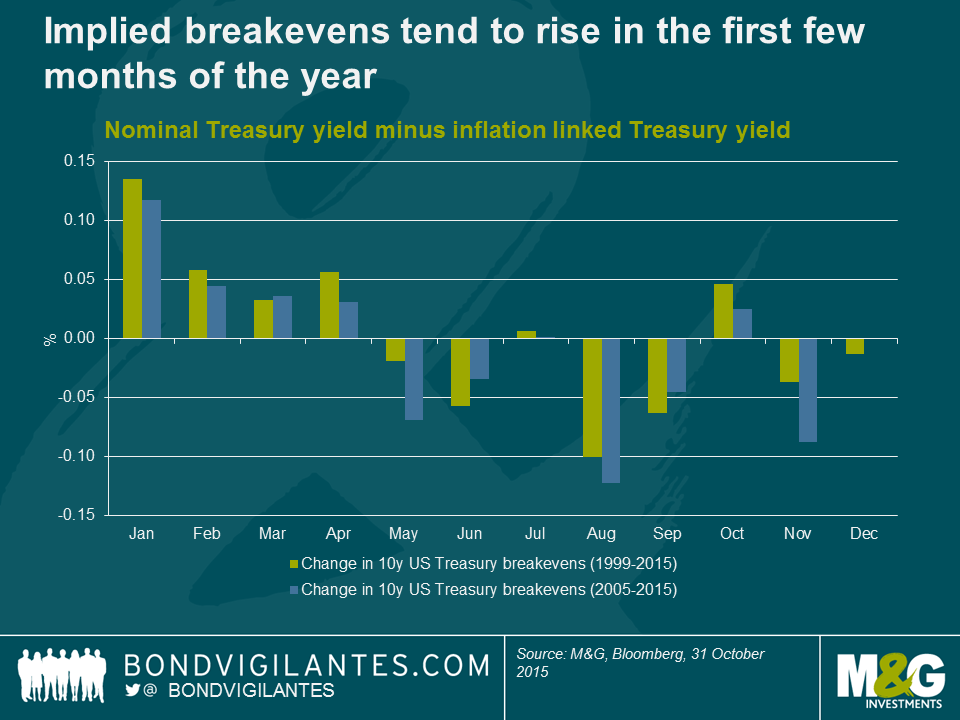

One way to look at cash products would be to look at the implied breakeven, that being the nominal yield of a regular government bond minus the yield on an inflation linked bond of the same maturity, issued by the same government. The result is the inflation compensation and an inflation risk premium implied in nominal bonds. Thus looking at this differential between nominal bonds and inflation linked bonds we can get a sense of how the inflation component that is priced-in for nominal bonds behaves. Below we can see that in the period when inflation ‘seasonally’ tends to rise, implied breakevens on average tend to rise. We see implied breakevens on average tend to fall in August, September and November, which also coincides with the period inflation ‘seasonally’ tends to be weak. As an aside, the ECB and the Fed in recent years (http://www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/notes/feds-notes/2014/residual-seasonality-in-core-consumer-price-inflation-20141014.html ) also have made the observation that seasonality in consumer prices has become stronger, some of which is due to changes in methodology/measurement.

Why does this matter?

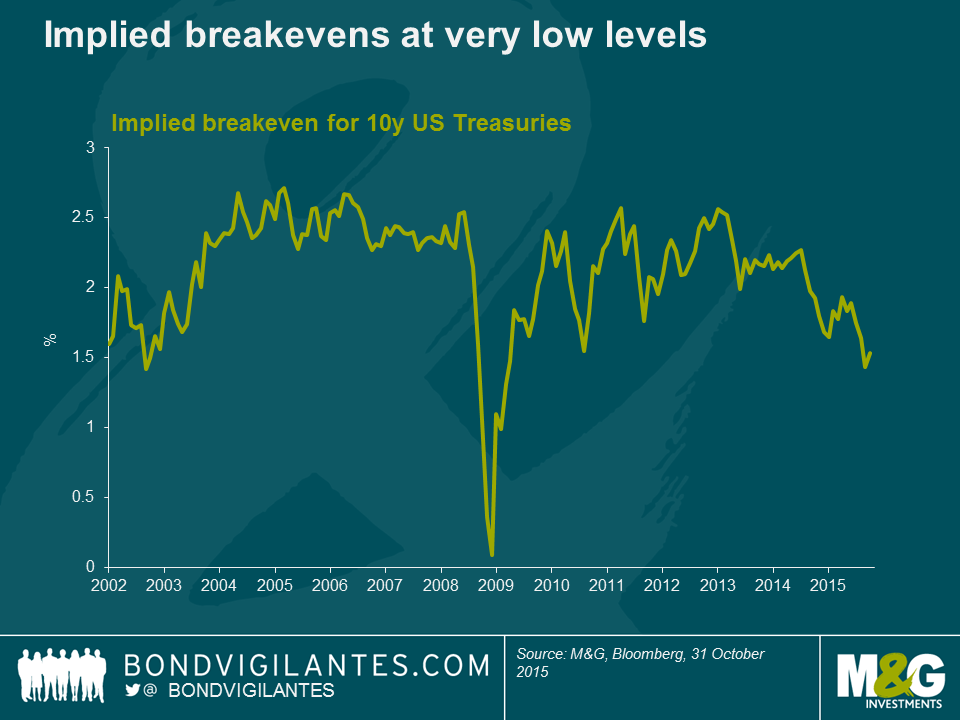

In the below chart we can see that the priced-in inflation compensation (ie implied breakevens) is very low at the moment, as consensus struggles to see what could be a catalyst for inflation, and given the supply/demand dynamics in energy, energy is expected to remain weak. However, we should keep in mind that the implied breakeven includes an inflation risk premium. This of course varies over time and is very hard to measure, but academics estimate it to be somewhere between 40-75 basis points. Thus when we observe 1.5% for the next 10-years, it actually is probably closer to pricing an investor compensation for inflation of somewhere around 1% for the next 10 years. Moreover, inflation is a rate-of-change concept, thus base effects are important and roll out after a 12 month period (ie for inflation to remain constant, prices have to keep on falling/rising at the same pace as in the prior 12 months). Thus with some tailwind from seasonals in the first half of next year, in combination with the base effect of energy rolling out, there could be scope for breakevens to drift higher.

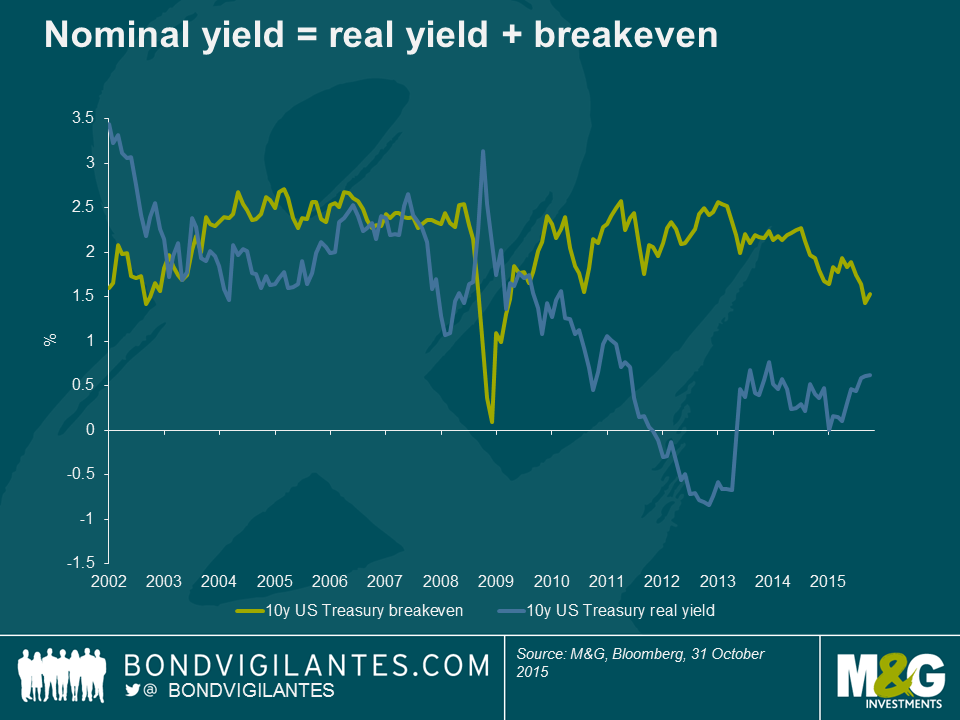

Financial repression by central banks pushed real yields down (preferably into negative territory to be most effective), but with the US economy normalising it would most likely be that real yields will be allowed to stay at current levels or even drift a bit higher at a measured pace (otherwise it would tighten conditions too much). Here we have seen some recovery from the 2012 bottom.

If we have a situation where the Federal Reserve hikes in December just as the base effects of energy start to fall out of the inflation numbers (compare headline at 0.2% with Core at 1.9%), coupled with the fact that implied break-evens tend on average to rise in the first few months of the year due to seasonally stronger rises in consumer prices, this could potentially provide quite some headwind for Treasuries over the next six months.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox