Why do people buy negative yielding bonds?

Guest contributor – Craig Moran (Fund Manager, M&G Multi-Asset Team)

The following blog was first posted on M&G’s Multi-Asset Team Blog, www.episodeblog.com. M&G’s Equities Team also regularly post their views at www.equitiesforum.com.

These are extraordinary times in financial markets. On a daily basis we are being bombarded with news headlines of political turmoil, market gyrations, forecasts of the un-knowable, and incomprehensible new technologies.

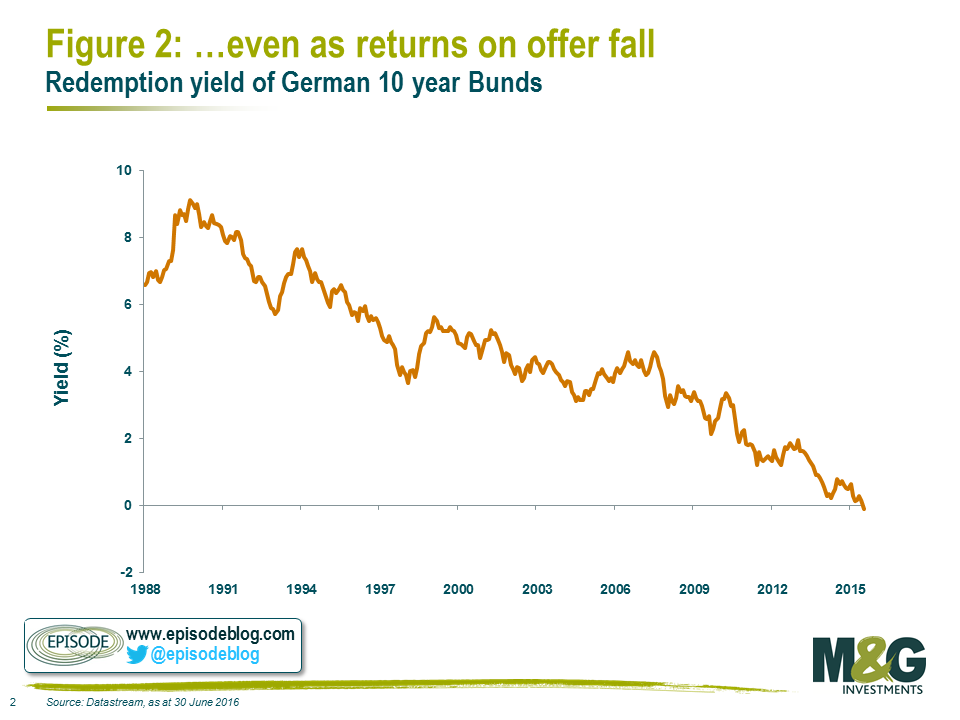

In amongst all of this chaos – one story that hasn’t attracted enough attention in financial markets was the news last week that the German government issued 10 year government bonds at auction with a negative yield. We also saw the first non-financial company (albeit state owned) issue bonds at a negative yield.

Whilst bond auctions don’t usually grab headlines, this does seem significant and as an event it perfectly encapsulates the risk averse environment that we now live in. While we’ve had bonds trade on the secondary market at negative yields, new issues with a negative yield only serve to emphasise the extreme nature of the current environment.

Bond terminology can be complicated, however to summarise the terms of this auction:

- Investors pay slightly over 100.5 euros to buy these bonds

- The bond pays no coupon and produces no income over the entire 10 years

- In 10 years time, investors receive back 100 euros

Our approach to investing involves seeking to identify and exploit markets behaving in an irrational manner. At first glance the transaction I’ve described above doesn’t seem like a rational one, but it’s important to challenge ourselves as well as the market to identify if we have a quarrel with its behaviour. So let’s examine the possible reasons why a rational person might engage in a transaction like this.

Rational reasons for buying 10 year government bonds on a negative yield

- Sell them to someone else at a higher price

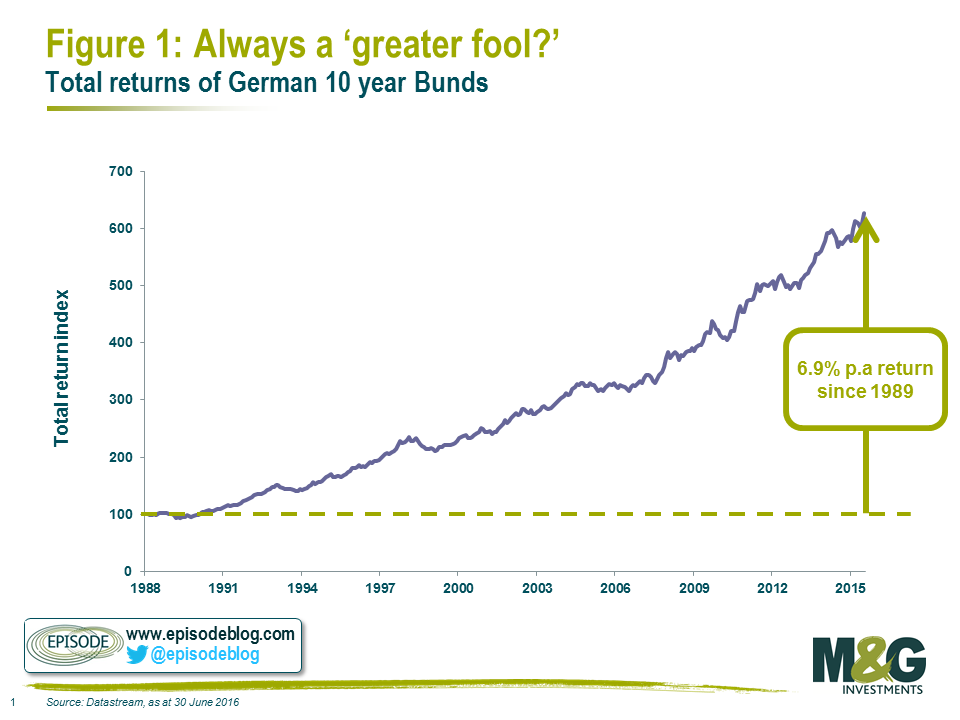

One of the main motivations for buying financial assets is to make a positive return, either in the form of income received, or to sell to someone else at a higher price. In the case of this particular transaction there is no income – so we can rule that out. The possibility of selling the asset to someone else at a higher price (a greater fool) is predicated on hoping that having accepted a guaranteed loss of over 50 cents over the course of 10 years, someone else will be willing to accept an even greater guaranteed loss over a shorter time period at some stage in the next 10 years. It’s betting that bond prices will hit ever higher highs, and yields hit ever lower lows.

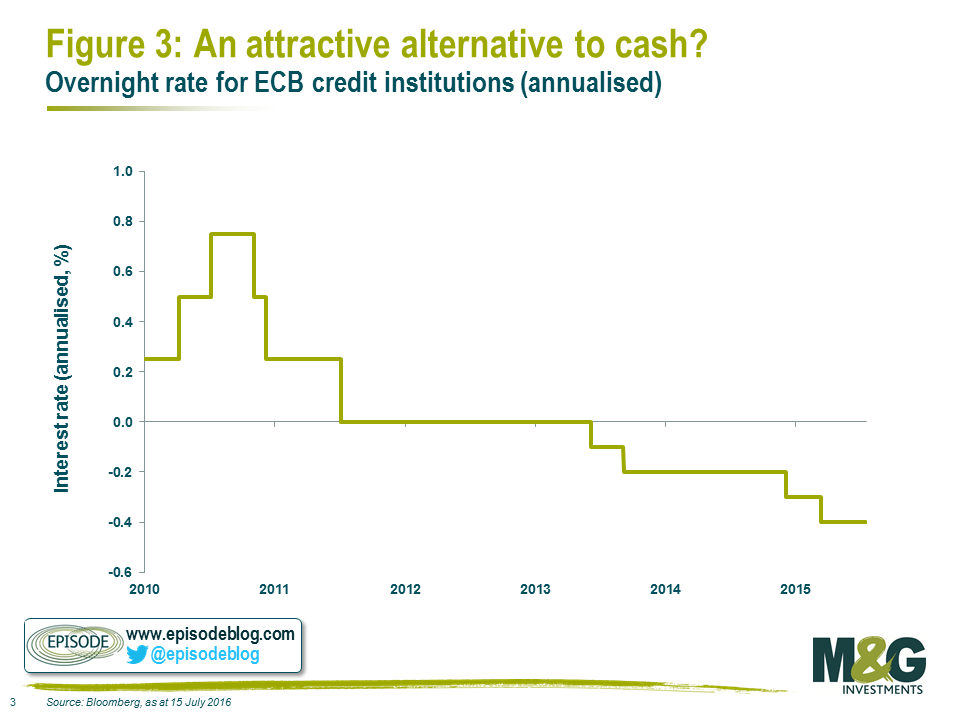

- Cash rates are negative

The current ECB Deposit rate is -0.40%, so storing your money overnight with a European bank will cost you an annualised rate of -0.40%. So suddenly the yield on the German government bond at -0.10% annualised doesn’t sound so bad, right? Especially if at some stage that overnight deposit rate might go even lower, although lately it seems policy makers seem to be growing weary of taking cash rates even lower.

However, even though the bond offers superior yield (less bad at least), in order to guarantee this outperformance you need to hold the bonds for the full 10 years and have cash rates stay where they are now.

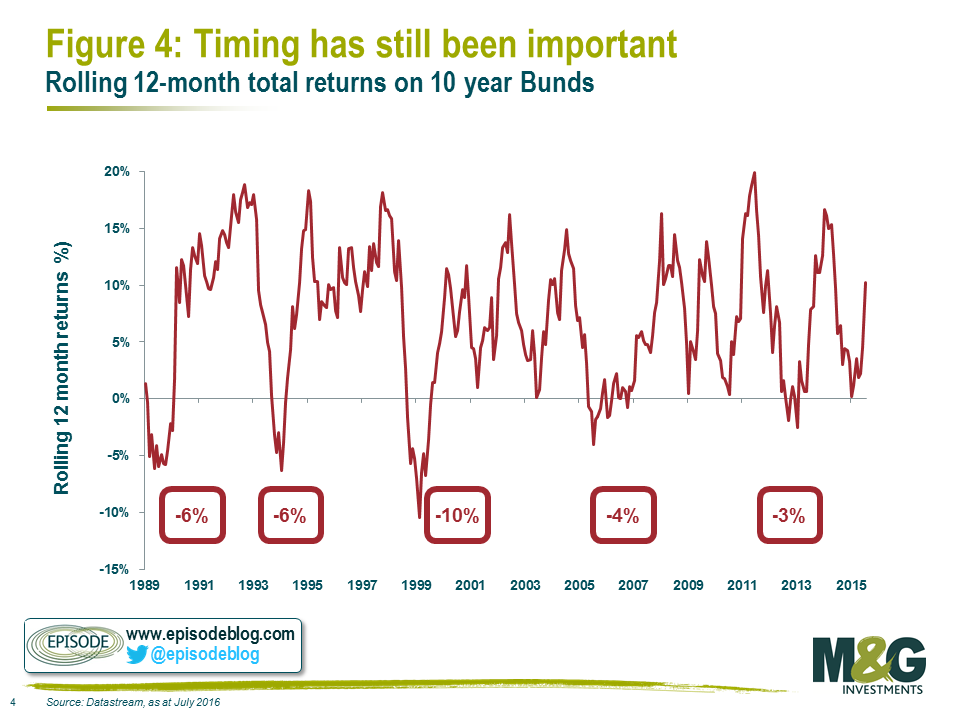

Should rates change, or you want access to your cash prior to the 10 year expiry, you are beholden to the market as to what price you will be able to sell your government bond for at the time you want to sell it. The bond has a duration of 10yrs, so should interest rates, or expectations of interest rates move only 1%, we could see a fall of up to 10% in the price of the bond.

Even in the 30 year bond bull market there have been plenty of occasions where transacting at the wrong time would have been an expensive exercise.

A cash proxy shouldn’t expose you to such timing considerations. Even if institutions are using the Bunds as places to store cash over the very short term, it seems a potentially expensive gamble to take given a modest yield advantage.

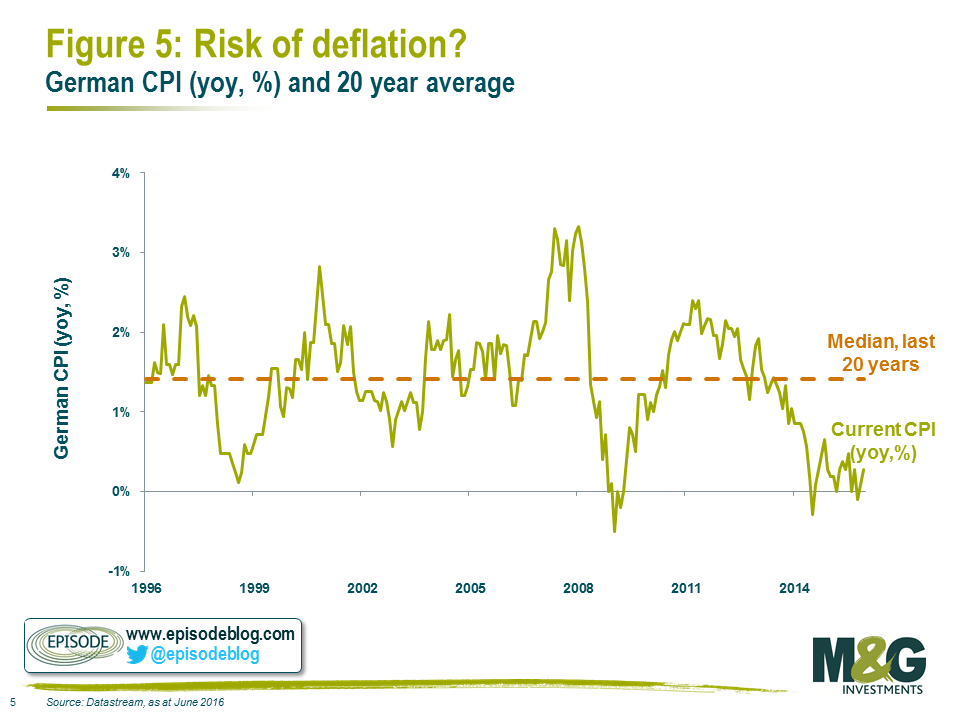

- Deflation

Conventional economic thinking suggests that money available to spend today is worth more than money available in the future, thus investors should be compensated for deferred consumption. If, however, you are in a regime of falling prices, it may be the case that 100 euros 10 years from now has more purchasing power than 100 euros today.

This is the chart of German CPI over the past 20 years. Despite multiple economic crises, it has spent very little time below zero (deflation), and averages around 1.4%.

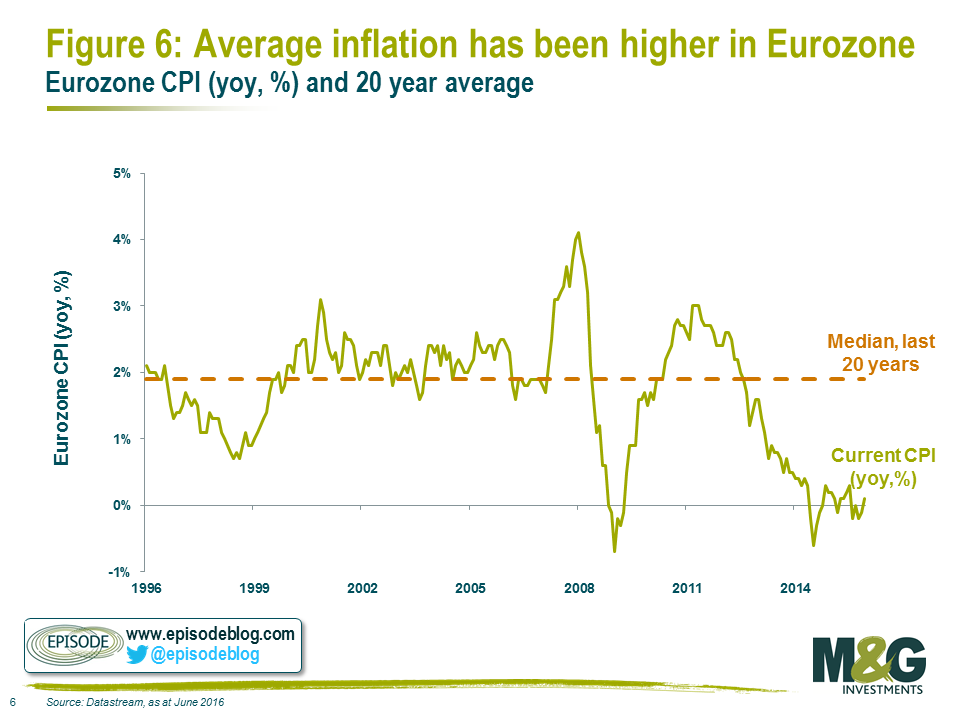

Even looking from a Europe-wide perspective, the current level of inflation is lower (-0.1% versus +0.3% for Germany), though the long term average is higher at 1.9% (versus 1.4% for Germany).

Given the history of European inflation, and knowing that policy makers globally are doing everything in their power to avoid deflation (due to over-indebted balance sheets across Europe), a bet that deflation will persist over the next 10 years in order to compensate for negative yields today seems to be a bold one.

Other reasons for buying 10 year government bonds on a negative yield

- Regulation

Today’s regulatory environment continues to favour the purchase of government bonds vs other assets, however into the medium term it’s difficult to envision regulators encouraging banks and insurance companies to purchase assets with guaranteed negative returns. The fact that there’s a non price-sensitive/economically motivated entity temporarily distorting asset prices should always pique the interest of free market participants.

- ECB QE

This is a combination of points 1 and 4. Currently there is a non price-sensitive buyer in the market for European Government bonds. Any unencumbered buyer of these bonds in the auction is hoping that the ECB will continue to buy these bonds at ever higher prices disregarding the economic payoffs of doing so.

Or could it be…

- “Safety”

One thing that most market participants would agree on is the fact that there is a high probability that you will get your money back if you buy these bunds – albeit slightly less than you initially paid. It seems today the most likely reason investors are buying this bond (and many, many others at similar yields) is certainty. As we’ve stated before, return of capital has replaced return on capital as investors’ main priority.

This is where our biggest quarrel with the market lies. Safety, or certainty, like everything else – has a price. A guaranteed negative return on an asset held for 10 years seems like far too high a price to pay today for this perceived safety, especially given where the same ‘safe’ asset has been priced historically, and where it could trade again should risk preference or fundamentals change even modestly.

When it’s difficult to find any rational reason for buying something, should rational investors be thinking about selling it instead?

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox