European Central Banks: it’s not just the ECB meeting on Thursday

While the market gears up for the much anticipated European Central Bank meeting on Thursday, there are two other European central banks due to meet earlier in the day; Sweden and Norway.

I was in Washington a couple of weeks ago for the World Bank and IMF conferences, which was a great opportunity to hear from policy makers and economists. It served as a timely reminder that the European central banks are likely to be more patient (i.e. dovish) than market participants expect – especially those with strong trading links to the Euro area. In the case of Sweden, it has taken 6 years for growth to pick up and maintain a convincing upward trend, inflation and expectations also. Policymakers will not be in a rush to tackle rising inflation prematurely.

There’s been much speculation about whether the ECB will tweak or begin preparations to exit its quantitative easing (QE) programme. The Swedish Riksbank has been implementing its own quantitative easing and although the economic fundamentals in Sweden have been improving, indicating for much of this year that normalisation is perhaps warranted, I do not anticipate this being tweaked ahead of the ECB announcement. This is because what’s especially pertinent for Scandinavian nations – particularly Sweden, Norway and Denmark – is that as small open economies with large shares of GDP derived from trade, it is the exchange rate which acts as the key transmission mechanism for monetary policy (Denmark with its currency peg, is obviously more explicit about this).

Given that both Sweden and Norway have strong economic links to their Eurozone trading partner, neither the Swedish Riksbank nor the Norges Bank would want to see their respective currencies appreciate (and their inflation target missed) by implementing hawkish monetary policy. This would only serve as a first-mover disadvantage. They too, will be in wait-and-see mode on Thursday with respect to the ECB, before they embark on their own policy normalisation path.

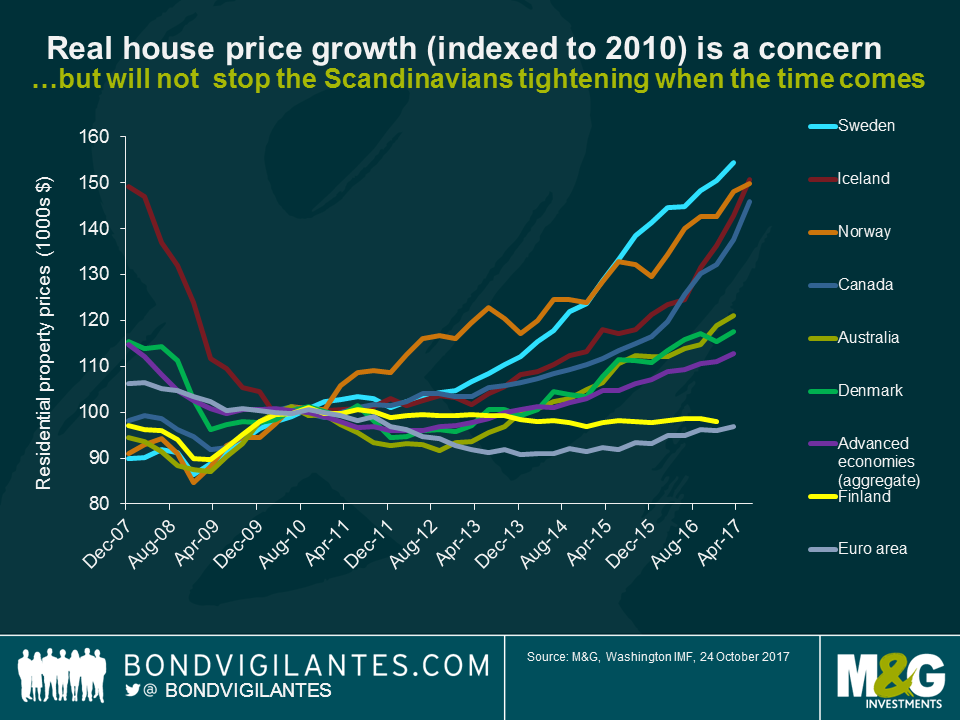

The final point worthy of note is with respect to leverage in the housing sector. The chart below shows how this is a growing problem, not just in Scandinavia, but in countries such as Canada and Australia too. It is difficult to find research which doesn’t cite this as a growing problem in these economies, often pairing this reasoning with arguments why central bankers will not be able to hike rates significantly. Scandinavia essentially needs two interest rates; one (which is much, much higher) to curb the housing market and a second one (to remain low) for corporates to ensure they remain competitive versus the continent.

Since the meetings in Washington however, I have noticed just how many central bankers worldwide have been at pains to stress that financial stability is not their key remit. Household debt is on their radar but it’s a problem for macro-prudential tools or politicians to deal with and not traditional monetary policy. The ball is being shifted to someone else’s court. If and when the Scandinavian central bankers do embark upon their rate hiking cycles, it will not be housing sector concerns that stop them from doing so. Market participants would do well to remember that central bankers may be agnostic towards housing market excesses when the tightening cycles ensue.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox