Panoramic Weekly: 2019, fasten your seatbelts?

The new year has started with a blunt reminder of probably everything that investors wanted to forget over the holiday season: economic data is worsening while the oil price continues to fall, dragging down equities and the most equity-like fixed income asset classes. Traditional safe-havens continue to rally, as they did in 2018.

The year left behind ended far worse than it started: after a strong-growth 2017, where most fixed income sectors delivered positive returns, last year’s early hopes quickly sank with the escalation of the US-China trade war and the Italian elections in May, which raised questions about the future of the European Union (EU). Fears of a hard Brexit also weighed on the continent’s economic prospects, lifting credit spreads above those in the US for the first time in years. China continued its slowdown, while in the US, optimism started to fade as interest rates rose, economic data disappointed and oil plunged to less than $50 per barrel amid forecasts of weak demand. US corporate earnings projections were also reduced as the effects of the recent tax cuts started to decline. The world benchmark US 10-year Treasury yield, which reached a 7-year high of 3.2% last year, changed gear after the Democrats won control of the House of Representatives in the November mid-term elections. Investors believed that their victory reduces the chances of further tax incentives from President Trump. The 10-yr Treasury yield has been on a continuous slide since, ending 2018 at 2.66%.

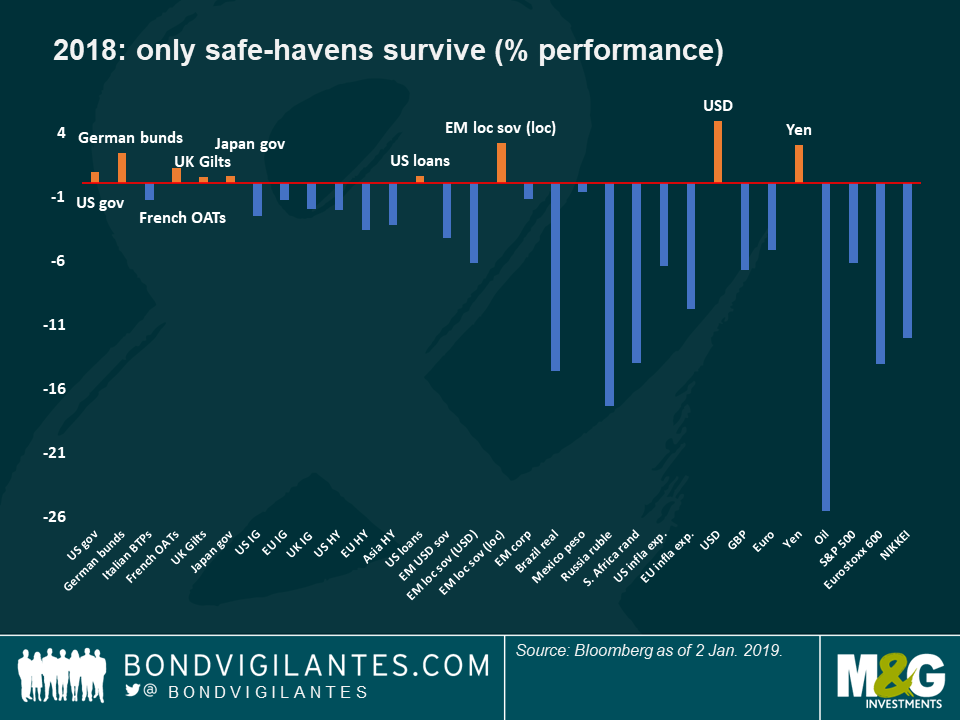

Despite the pessimism, almost one third of the 100 fixed income asset classes tracked by Panoramic Weekly delivered positive returns last year, led by traditional safe-havens, such as German bunds and US Treasuries. With global growth slowing down and global debt reaching a whopping 225% of world GDP, investors are betting some central banks may have to rein in their rate hike projections – offering more support to bond prices. US Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell already did in December – the Fed now sees 2 rate hikes this year, instead of 3. The M&G Panoramic Weekly team wishes you a very happy new year.

Heading up:

Safe-havens – the best of times in the worst of times: US Treasuries, European government bonds and Japan’s sovereign debt did in 2018 what they usually do: deliver positive returns, rain or shine. While corporate debt markets and developing nations suffered from higher interest rates, a stronger dollar, the ongoing trade wars and lower global economic growth, traditional safe-havens remained solid. Treasuries have only posted negative returns in 2 of the past 18 years (2009 and 2013), while European and Japanese government bonds have only missed 1 year of positive returns (2006 and 2003, respectively), over the same period. Sovereign bonds have been favoured by protracted global low inflation, a backdrop that may continue going forward given the recent plunge in oil prices. Weaker growth and rising global debt may also refrain central banks from tighter monetary policies: out of 19 major economic areas, 5 are projecting lower rates in 3 years’ time (the US, Mexico, the Czech Republic, Japan and Korea), compared to none barely 2 months ago, according to Bloomberg data. In terms of currencies, safe-havens have also outperformed, mainly the US dollar and the yen. As Dickens would have put it, for safe-havens, it was (is?) the best of times, it was (is) the worst of times; it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness…

China government bonds and loose policy – odd one out: China’s USD-denominated sovereign debt returned 3.8% to investors in 2018, the third best performer among the 100 fixed income asset classes tracked by Panoramic Weekly. The rise comes despite a slowdown in economic growth, now down to an annualised pace of 6.5%, from 6.9% last year. The country’s manufacturing PMI dropped to 49.4 in December, the weakest since 2016 and below the 50 level that marks a contraction. Yet, the Chinese government’s stimulus policies, including cuts in the banks’ reserve requirements, continue to support the economy and the bond market. Still mostly in the hands of local investors, Chinese debt is increasingly available to foreign holders via the Bond Connect programme, and may be more in demand after it is included in some Bloomberg Barclays benchmark indices from April this year. In the present global rate rising environment, investors welcome a country with an overall easing policy.

Heading down:

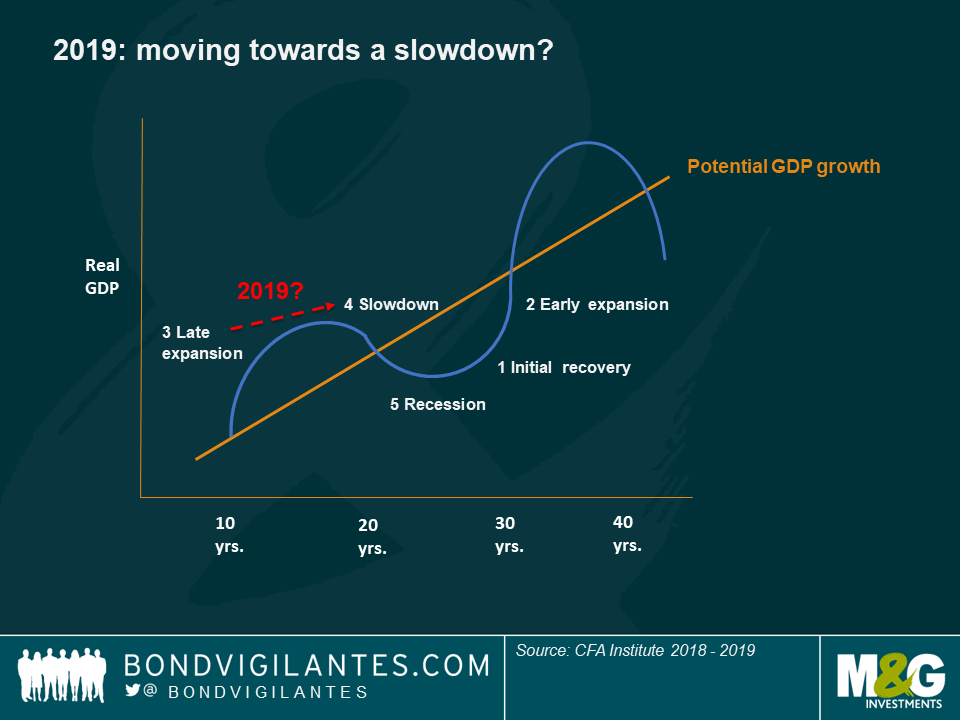

Business cycle – down-sloping? With the last recession now a decade ago and economic theory suggesting that cycles tend to last about 10 years, investors are understandably concerned – hence their preference for safe-havens over risk assets. But more than timing, the nervousness comes amid other signals: during the late expansion phase of a business cycle, economic growth tends to be above the long-term trend growth, but the pace starts to slow down. In the US, for instance, growth is expected to drop to 2.6% this year, and to 1.9% in 2020, down from an expected 2.9% in 2018. This “late expansion” phase is also characterised by restrictive policies (which we are seeing around the world as central banks move from Quantitative Easing to Quantitative Tightening), and by rising inflation (in the US, inflation is expected to rise to 2.4% in 2018, up from 2.1% in 2017). Interest rates are usually higher (the 2-year Treasury yield, the de facto world’s discount rate, leapt from 1.8% to 2.49% in 2018), bringing volatility to equity prices (the S&P 500 index lost 6.2% last year). If this “late expansion” narrative applied well in 2018, the new year might bring us the following “slowdown” phase, where we usually see: slower growth (already forecasted), peaking consumer confidence (this is a lagging indicator as consumers typically need to see weak data before holding up purchases), a cooling off of restrictive policies (Fed chair Powell could have already signalled this in his dovish December speak), as well as higher inflation (also in the cards in the US). In this environment, long term bond yields usually drop as investors discount the slowdown, while equities suffer from the anticipation of a future recession, which would be the next stop. As usual, opinions vary: while the Fed sees 2 rate hikes next year, and further tightening in 2020, markets are pricing in no hikes at all this year, and cuts afterwards. Nobody knows what the future holds, but over the past few years, markets have been better predictors than then Fed.

EMs – tough year: Emerging Markets (EMs) USD-denominated sovereign debt fell 4.3% last year, the third annual loss over the past 18 years (the others being in 2013 and 2008). The period also includes ten years of double-digit positive returns, as the asset class benefited from strong global growth in the early 2000s, while remained relatively immune to the 2007-2008 financial crisis given its lower banking problems. But 2018 brought them a toxic mix of a rising dollar, falling oil prices (which hit oil-exporting EM heavyweights such as Brazil, Mexico and Russia), trade wars and idiosyncratic problems in Argentina and Turkey. All this hit African, Middle Eastern and Latin American countries the hardest, with Eastern Europe and Asia remaining more resilient. Some investors argue that the fate of EMs may change this year as the ‘twin deficits’ in the US may contain any dollar surge while global growth is forecast to stay positive, albeit unspectacular. Some also believe that with yields at 6.8%, the highest since 2009, risk might be compensated.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox