Should investors care about GDP data revisions in emerging markets? A Benin case study

Statistical data represents only an approximation of reality, and sometimes not a very good one. Generally, the less economically developed a country is, the worse the quality of the data provided by the government authorities. This increases the likelihood of later revisions, as new facts are uncovered or the methodology adjusted to better reflect the changing reality. Investors in emerging markets are well-accustomed to making their decisions based on such caveats, but data inaccuracies can be significant and revisions after the initial release of data are common.

Arguably, the most important macroeconomic indicator of a country is its GDP. According to a 2016 study by the Office for National Statistics in the UK (which compared the GDP revisions of OECD countries), most countries tend to underestimate GDP growth in their early data releases. Estimating GDP during turning points in the economic cycle has proven to be particularly problematic, with larger revisions increasing around those periods. Overall however, the revisions for OECD countries tend to be relatively small, even a few years after the initial release, very rarely exceeding 0.5% of GDP.

The situation can be different in emerging market economies, where revisions tend to be larger; even in those countries with well-developed economic statistics. For example, real GDP growth for Turkey in Q4 2016 and Q1 2017 was revised by 1% and 0.7% of GDP respectively, as soon as the quarter after the initial release. In another example, Russia’s GDP growth for 2015 was revised to -2.5% a couple of years after the initial estimate of -3.7%, while 2016 was revised up to +0.3% from -0.6% earlier. These revisions however are insignificant when compared to those observed in some of the frontier markets of Africa and Asia. In recent years, a few Sub-Saharan Africa economies have seen GDP revised up by as much as 25-40%. A standalone case is Nigeria which revised its GDP up by 90% in 2014, making it the largest economy in Africa overnight.

How should the market react to such revisions? Well, in many cases the revisions appear warranted. In fact, the IMF recommends the base years used for GDP calculation to be updated every 5-10 years. This especially applies to countries with rapidly changing economic structure as the role of IT, telecom and financial sectors rises. In addition, the share of shadow economy in developing countries also tends to be high, leaving significant potential for the governments to formalise and include it in GDP. For example, in Nigeria’s case the reference base year for calculating GDP was 1990, indicating that the 2014 revision was clearly long overdue. The structure of GDP also significantly changed: the services sector share of GDP doubled to 50%, at the expense of the hydrocarbon and agriculture sectors.

The latest trend appears to be an announcement of an upcoming GDP revision – rather conveniently – just before a debut Eurobond issue. In February, Uzbekistan made a successful placement of five-year and ten-year Eurobonds (USD 500 million each) at favourable yields. A few months prior, the country’s GDP data was revised upwards by 18% for 2017 and 28% for 2018. While this revision improved the country’s public and external finance ratios, it is nevertheless unlikely to have caused a material increase in investor demand for the Eurobonds. The reason is that Uzbekistan’s public debt has been low anyway, having stabilized around 25% of GDP. Meanwhile, the country has very high international reserves at 55% of GDP (one of the highest ratios globally) which more than covers its external debt. In fact, the positive investor sentiment was likely driven by an ambitious reform programme launched by the government, with the first successes already visible. As part of it, the quality and availability of statistics also improved, which was recognised by the IMF.

This week another reform-oriented country, Benin, is planning to take advantage of relatively favourable market conditions by issuing a debut Eurobond. The fundamental case for investment appears to be somewhat weaker though. While GDP growth rates have been robust in recent years, the economy is very highly exposed to agriculture and its main trading partner, Nigeria. Running high current account deficits in recent years has led to a rapid accumulation of external debt which jumped to 28% of GDP in 2018. A somewhat mitigating factor is the country’s membership in the West Africa Economic and Monetary Union. At the expense of an independent monetary policy, it provides Benin with low inflation and access to the union’s pooled international reserves (the country’s own reserves are low). However, the main pressure point has been the fiscal policy. The country was running 6-7% of GDP budget deficits for a few years, causing public debt to rocket from 25% of GDP in 2013 to 55% of GDP in 2018. The government has recently embarked on an ambitious fiscal consolidation path, but risks are to the downside given the uncertain efficiency of new tax measures and the upcoming election period (parliamentary elections are scheduled for April this year, while presidential elections are due in 2021).

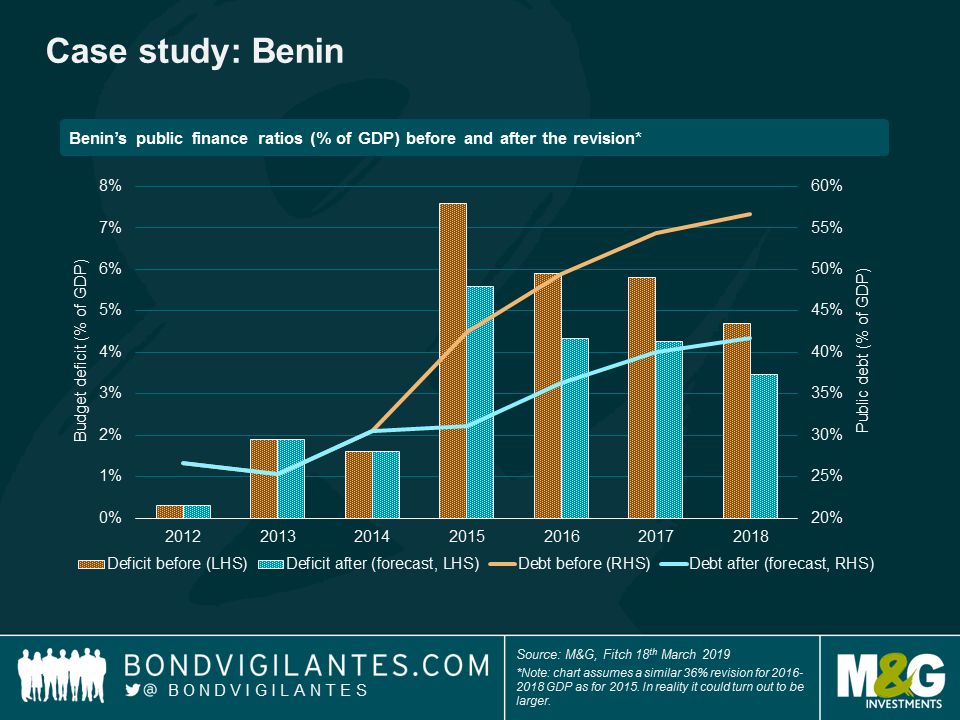

With regards to data revisions, a few months ago the authorities announced that 2015 GDP would be revised up by at least 36% (the revisions for subsequent years are not yet finalised). On the one hand, the necessary formalities have been observed – the country will update its base year from 2007 to 2015 in collaboration with the IMF, change the methodology to the latest one adopted by the UN, and improve its coverage of the informal sector. On the other hand, the timing of the announcement of the revision is questionable. The new GDP figures are not yet incorporated in the official statistics (the revisions are expected to be finalised later this year), but it is already clear that the worrisome fiscal and external finance ratios are likely to significantly improve as a result. In particular, high budget deficits would no longer look so alarming, while public debt would “drop” closer to 40% of GDP.

How should the market perceive these upcoming changes? Opinions already differ at the credit rating agencies. In its December 2018 report, S&P mentioned that “the rebasing is unlikely to have any effect on Benin’s sovereign credit rating”. In a stark contrast, Fitch in its March 2019 report listed “an improvement in public and external finance ratios resulting from revisions of national accounts statistics in line with international standards” among the main factors that could trigger positive rating action. The fair approach is perhaps somewhere in the middle, though my personal opinion is somewhat closer to the S&P’s position.

There are a few points to keep in mind. Firstly, while Benin’s debt ratios are expected to significantly improve, the direction of government policies should be clearly more important from investors’ perspective. Given the evidence of rapid debt accumulation in recent years, Benin could be back to having above 50% of GDP debt ratio in just two-three years, should the current expansionary policies fail to adjust. Secondly, in theory, the inclusion of the previously unrecorded informal sector should have consequences not only for GDP, but for all other economic indicators as well. For example, one consequence could be higher government spending and more difficult revenue collection from the newly-included parts of the economy (implying a likely drop in revenue to GDP ratio), which could lead to a structural deterioration of Benin’s fiscal balances. Finally, the degree of a country’s indebtedness does not necessarily have to be represented only as a ratio to GDP: for example, Benin’s high debt-to-revenue ratio might not change as significantly, if the previously unrecorded part of the economy does not generate a lot of revenues.

What will investors make of all these arguments? We will likely know very soon as Benin places its Eurobond this week.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox