The 2020 geopolitical risks that matter for emerging markets

Last year was very eventful in emerging markets with its share of US tariffs/sanctions, regime changes in many countries, mass protests across the board and Carlos Ghosn escaping Japan to soon-to-default Lebanon on the very last day of the year! 2020 promises many geopolitical risks. We have compiled some of the key risks below for developing economies, including “the biggest crisis no one is talking about”. Brexit has been intentionally omitted.

Persian Gulf tensions: One knows geopolitical risk matters when a few unsophisticated drones can suspend 5% of global oil supply (or 50% of Saudi Arabia’s oil capacity) over one night. It happened in September 2019 and it reminded everyone not only how fragile the Persian Gulf status quo was but also the far-reaching impact any type of escalation could have for the rest of the world with crude oil up +15% the day following the drone attack. Whilst the strait of Hormuz crisis seems to have abated in the second half of 2019, Iran now faces parliamentary election in February 2020 in a context of a sharp economic recession (IMF predicts -9.5% GDP growth in 2020) after two years of unilateral sanctions from the US (since May 2018). Elections could well revive tensions this year and escalation in the Middle-East could have a significant impact on asset prices in the region as the risk premium remains relatively low in some stronger-rated countries such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait or the UAE. Some weaker countries like Bahrain or deteriorating credit stories like Oman are even more vulnerable. Finally, another source of concern is Iraq where public discontent is growing quickly on the back of government corruption allegation. Elections in 2020 are a possible scenario and Saudi Arabia’s influence in the country has increased in order to counter-balance Iran’s alleged control of some Iraqi Shia militias. The pro-Iranian demonstration at the American Embassy in Baghdad a couple of days ago, followed by the US killing of a top Iranian General in Iraq on 2nd Jan, are here to remind us that the US-Iran tensions are unlikely to vanish in 2020.

US-China trade war: This is one of the biggest risks for emerging markets whose economies continue to rely extensively on global trade. The main channel of contagion comes from weaker Chinese GDP in turn resulting in lower demand for commodities. For instance, Sub-Sahara Africa is China’s second-largest supplier of crude oil after the Middle-East and also provides metals. Since 2014, most countries in the region have seen a significant decline in trade with China after two decades of growth. The US-China trade war has obviously exacerbated the global trade problem and some Asian economies are now seeing falling supply-chain related exports due to the decline in China exports to the US. However, some developing countries have emerged as winners. Vietnam, Mexico, Malaysia and Thailand all have benefited from either a direct rise in exports due to diverted US demand from China and/or an indirect rise in exports related to the supply chain of China’s competitors. There is also hope for a sustainable deal between China and the US which would revive global growth in 2020 and beyond. In December, both parties agreed on the “phase one” deal with some reduced US tariffs in exchange of improved protection for US intellectual property and additional purchase of US products from China. Rather truce than a deal though. The trade war is likely here to stay.

Taiwan elections, Hong Kong, North Korea and South China Sea: The incumbent President Tsai (Democratic Progressive Party) is likely to be re-elected in the Taiwanese January 11th presidential elections. Her party benefited from stronger economic data in recent months thanks to the US-China trade war which redirected some manufacturing to the island. The Hong Kong protests have also helped the independence-leaning party to gain ground over rival and more China-friendly opposition party. In Hong Kong, the protests that started in June 2019 are due to continue in January as the pro-democracy protesters now have more political capital since the landslide victory at the Nov-19 local elections. The domestic issues, coupled with the US-China trade war, have had a sharp impact on economic activity and job losses. The Chinese authorities have so far been relatively quiet but that might change after the Taiwanese elections. Elsewhere in Asia, year-end 2019 had its share of geopolitical escalation. North Korea said that it was considering new missile testing, against the commitments taken to denuclearised the Korean Peninsula. Malaysia recently joined Vietnam and the Philippines in their tough stance against China’s claim that the whole South China Sea belongs to China. The South China Sea has long been contested by many parties due to its geostrategic importance (military, shipping lines, natural resources).

US election: Another key geopolitical risk as Trump has been the most unpredictable US President in recent decades and in particular when it comes to foreign policy. The new US sanctions and tariffs the world has experienced since he took office are numerous (EU steel & aluminium tariffs, NAFTA renegotiation, China tariffs, Russia – although initiated by Obama, Iran U-turn, withdrawal of the Paris Agreement, etc.). Under a different US personality, emerging economies might not face the same unpredictability of one of the largest trade partners in the world and perhaps not constantly worry about the US dollar being used as a foreign-policy weapon. However, countries like Russia, Turkey or Saudi Arabia have benefited a lot from Trump’s relatively benign stance towards them and a change in the US administration may become bad news. On the economic front, most investors expect equity markets to reprice in the case of a Democratic victory. This would result in the Fed easing and a weakening of the USD. Whilst supportive of EM FX in theory, a weaker US dollar may also reflect a weaker US economy which would both impact US demand for commodities and affect risk assets across the world. In this scenario, EM debt as a whole may not perform well. Expect more clarity in March/April when the Democrat candidate could be known.

Turkey – US sanction risk: Turkey’s purchase of the Russian S-400 missile defence system – together with the October military operation in Northern Syria – have increased significantly the risk of sanctions from the US Congress. These could come in the form of visa bans for officials and asset freezes for state-owned bank Halkbank (Iran-related sanctions). The US have also threatened to close down two military bases in South-eastern Turkey. It remains unclear whether the US are willing to also implement broader financial sanctions on the banking sector as a whole, similar to what they did with Russia after the annexation of Crimea. Given Turkey’s banking sector’s huge need for short-term external funding, the latter option would bring material disruption to the Turkish economy and as a result is less likely because an implosion of Turkey would not be good news for either the European Union (Syrian refugees agreement with Erdogan) or the US (Russia would likely increase its influence in the region). Policy mistakes are another key risk, such as an aggressive monetary and fiscal easing to achieve the government’s unrealistic 5% growth target for next year. Bond spreads in Turkey, whether sovereign or corporates, have rallied hard late 2019 and barely reflect either policy-making or US sanction risks. Asset prices leave little room for error in 2020.

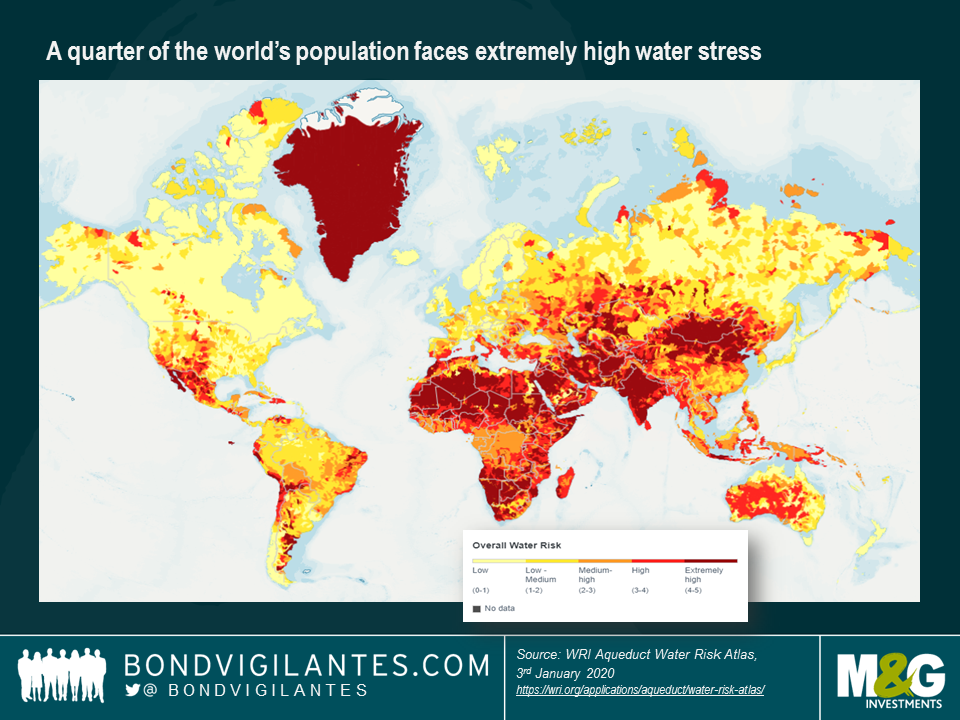

Water Stress – “The biggest crisis no one is talking about”: In August, this is how the World Resources Institute (WRI) – which focuses on climate, food, forests and other environmental and social issues since 1982 – described global water stress risk. The June-2019 Chennai water crisis was just an example of this, when tap water had stopped running in India’s fourth-largest city (8 million people) after two years of bad monsoon rainfall and also because rivers are polluted with sewage. Unlike the emotionally-driven climate activism from Greta Thunberg, global research organisation WRI published in August 2019 a research-backed Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas (cf. picture) which found that 17 countries accounting for a quarter of the world’s population were facing extremely high water stress with consequences “in the form of food insecurity, conflict and migration, and financial instability”. Developing economies are increasingly aware of water management because water scarcity / stress may act as a real impediment to social and economic growth if not properly managed by countries. There are other ESG factors that matter for growth but investors tend to focus on the geopolitics of oil, climate risk in general or deforestation. Too few investors are really looking at water stress as a structural risk of economic, political and social issues. The 2017-18 Cape Town or the 2019 Chennai water crisis are examples of water stress that constrained economic growth and brought social discontent. But water stress can also contribute to escalation of armed conflicts like in Yemen or Syria where the water crisis has been a critical factor.

India/Pakistan: India PM Modi’s new Indian Citizenship Law passed in December 2019 has incorporated religious criteria for refugees or communities seeking naturalisation. The law provides facilitated eligibility to become Indian citizenship to Hindu, Jain, Parsi, Sikh, Buddhist, and Christian minorities – but not Muslims – from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Widely criticised, the new law has been the subject of mass protests across the country and in particular in majority-Muslim state territory Kashmir. Early 2019, the region again saw an Indo-Pakistan military standoff after a vehicle-borne suicide bomber killed over 40 Indian forces in February. On the economic front, Pakistan (credit rating B3/B-) is also under pressure after GDP fell sharply in 2019. The IMF programme requires aggressive fiscal and monetary targets which already have resulted in anti-government protests. Any escalation of geopolitical risk with India would not be welcome.

Russia/Ukraine: Will last year’s good news carry on in 2020? The conflict between Ukraine and Russia which started in 2014 after Russia annexed Ukraine’s Crimea peninsula – death toll of 13,000 to date – has considerably improved since the Paris Summit on 9th December. Presidents Putin and Zelenskiy agreed to fully implement an existing ceasefire and on 29th December a long-awaited prisoner exchange of 200 prisoners happened. Mid-December, after many months of negotiations Ukraine (through Naftogaz) finally signed a new gas transit contract with Russia (Gazprom). This should indirectly help Ukraine’s budget as Naftogaz is a state-owned entity. The IMF programme and reform agenda of new President Zelenskiy are other positive factors. But asset prices have largely priced in the positive trend with Caa1/B- rated Ukrainian sovereign bonds in USD trading as tight as just over 200 basis points for a 2021 maturity… and mid 400 bps for the 5-10yr part of the curve. Clearly the market is Putin a blind eye on any downside risk from geopolitics in Ukraine, rightly or wrongly.

Social unrest across the globe: It’s not a surprise to anyone when the French demonstrate with yellow vests or go on strike against the pension reform. However, the violent mass protests in Chile following a raise in Santiago’s subway fare took most investors by surprise in 2019. And last year saw an almost unprecedented series of protests against corruption, inequalities and long-standing regimes. In no particular order: Lebanon (PM resigned amid street protests), Sudan (President Omar al-Bashir was ousted after a coup d’état following mass protests), Algeria (President Bouteflika departed – he was in power for 20 years), Iraq (PM resigned), Bolivia (Morales resigned after protests), Puerto Rico (Governor stepped down), Iran (mass protests), Colombia (mass protests), Argentina (political change), Hong Kong, etc. The trend had started since the Global Financial Crisis but clearly accelerated in 2019 and whilst each protest has its own dynamics, to a certain degree they all shared the same claim for fundamental changes in the system they lived in. Have financial markets priced in the structural rise of populism that comes from public discontent? Surely there is more to come in 2020 and investors are not immune to new surprises like the Chilean protests.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox