QE goes global: the case of Indonesia

The COVID-19-induced slowdown of the past few months has been different from past crises for a number of reasons. One of the most significant differences has been the greater ability of emerging market central banks to provide support to their economies, as we wrote about a few weeks ago. An interesting example is that of Indonesia. Last week, Indonesia’s central bank (Bank Indonesia – “BI”) cut its main interest rate (its seven day repo rate) by 25bps, from 4.25% to 4%. This was the second consecutive 25 bps rate cut in two months, the fourth this year, and brings Indonesia’s interest rates more in line with its Asian peers. Like many other central banks, BI has had to perform a delicate balancing act between supporting the economy during the pandemic and maintaining investor confidence and a stable currency. Indeed, given 40% of total corporate and government Indonesian debt is denominated in foreign currency, ensuring a stable rupiah is critical to the country’s economic prosperity.

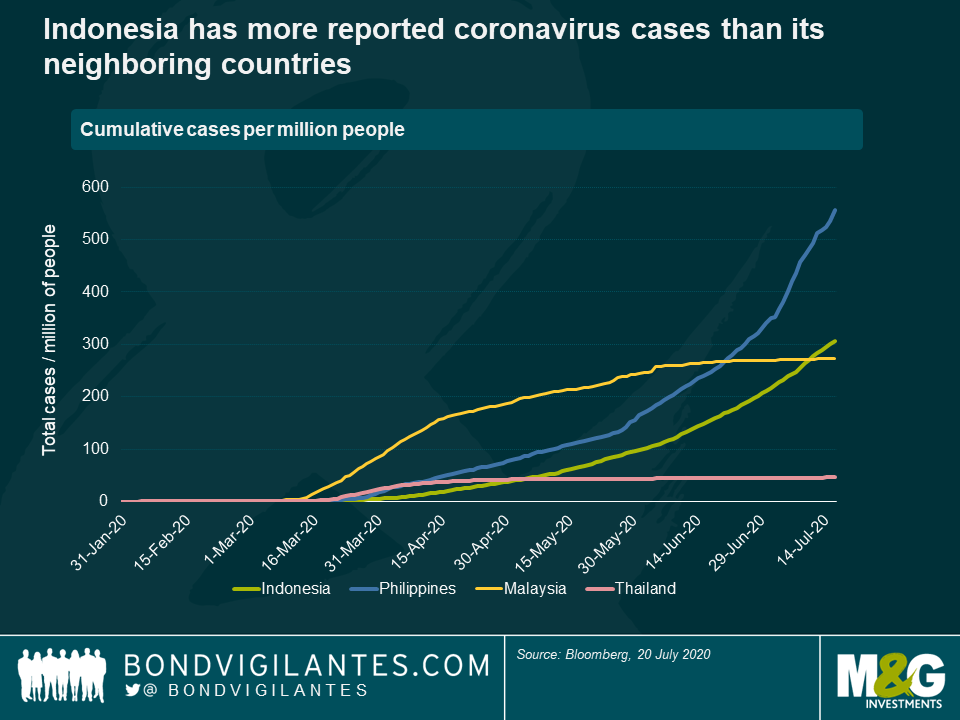

In order to contain the virus, the government started to impose large scale social distancing in March. Unfortunately, these measures have proven only marginally effective so far in preventing the spread of the virus, at least according to the official numbers (see chart below).

The recently imposed lockdown measures, combined with weaker global demand, have taken a significant toll on Indonesia’s economy. Real GDP growth is expected to be around zero for 2020, after averaging above 5% over the past decade. Imports are down around 14% versus last year, while unemployment and poverty rates are likely to increase substantially. As a result, the government announced a series of emergency stimulus packages aimed at directing more spending towards healthcare, social protection and businesses.

While the government has received some criticism for its ability to deploy assistance quickly in such a large and fragmented country, the initial pandemic response plan announced on 31st March was interesting for a couple of reasons. First of all, this initial plan allowed Indonesia’s budget deficit to increase beyond the statutory limit of 3%, until the year 2023. Indeed, as a precautionary measure, Indonesia’s budget deficit had been capped by law at 3% ever since the 1998 global financial crisis. For the year 2020, the government now expects the budget deficit to be 6.3% of GDP. Second, the regulation also stated that the government could finance the new pandemic spending plan through the issuance of additional bonds and, importantly, that these bonds could be purchased directly by the central bank.

This debt burden sharing scheme was finalized and revealed by the Indonesian authorities a few days ago. It provides for IDR 900 trillion of new debt-financed emergency pandemic spending (5.6% of GDP), of which the central bank will buy up to two-thirds via private placements and market auctions. This is expected to save the government around IDR 40 trillion in interest expense in 2020. More importantly, this will significantly reduce the supply of government bonds that needs to be absorbed by the private sector this year, helping to reduce yields and supporting the currency.

While BI has purchased Indonesian government bonds in the past, such an explicit and transparent reference to future debt monetization and collaboration between the government and the central bank is quite surprising for an emerging market. In addition, BI’s approach—aimed at reducing the interest burden for the government while maintaining higher interest rates and therefore the appeal of the debt for the private sector—is also relatively innovative.

On the flipside, BI’s actions raise the issue of central bank independence, moral hazard, and questions around how investors will react to a plan that directly subsidizes government spending and could encourage it to spend irresponsibly. To counter this argument, the Indonesian finance ministry points to the country’s track record of fiscal discipline and highlights the temporary aspect of the scheme, in that which is clearly an extraordinary state of events.

Economic textbooks also predict that such rapid increases in money supply should be inflationary. Research from Standard Chartered Global Research, looking at the historical relationship between changes in money supply and currency movements in Indonesia, concluded that the inflation rate could potentially increase by 2.4% all else being equal. That being said, one of the lessons of the past decade has been that the relationship between money supply and inflation can sometimes be quite tenuous, especially when private demand remains subdued. BI also has the option to tighten monetary policy (for example by selling back the special pandemic bonds or increasing bank reserve requirement ratios) at some point in the future, should inflationary pressures start to build up.

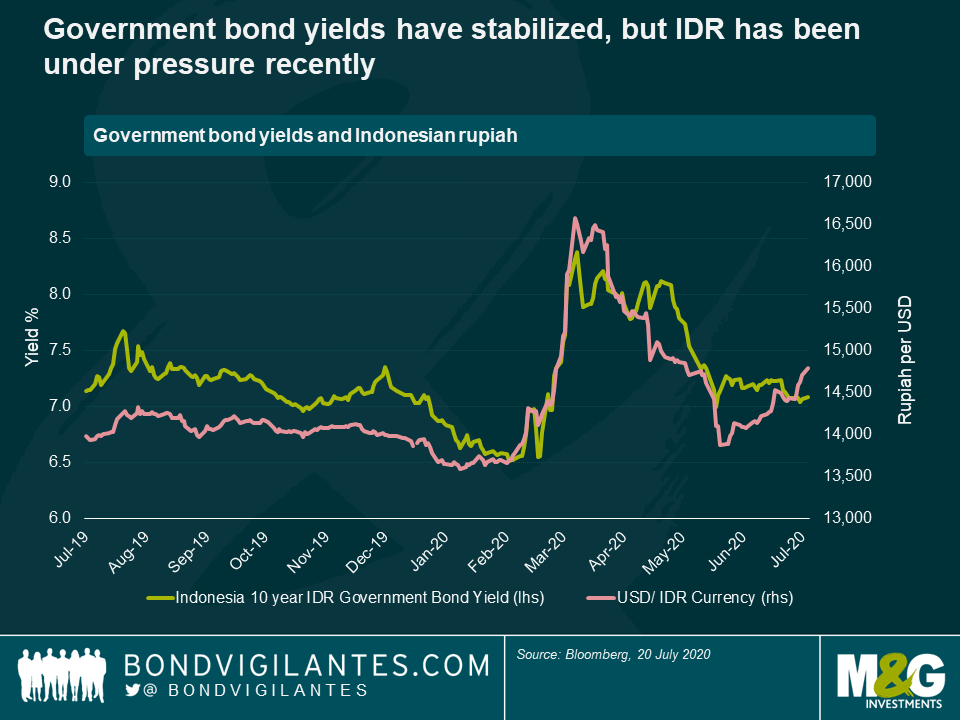

How have Indonesian local currency government bonds performed in this environment? After having sold off in March, government bond yields have stabilized. On the other hand, the currency has been under pressure once again over the past month, declining by 3.5% versus the US dollar. The cost of hedging Indonesia rupiah in the forward currency markets also remains relatively elevated, a sign of cautious investor sentiment.

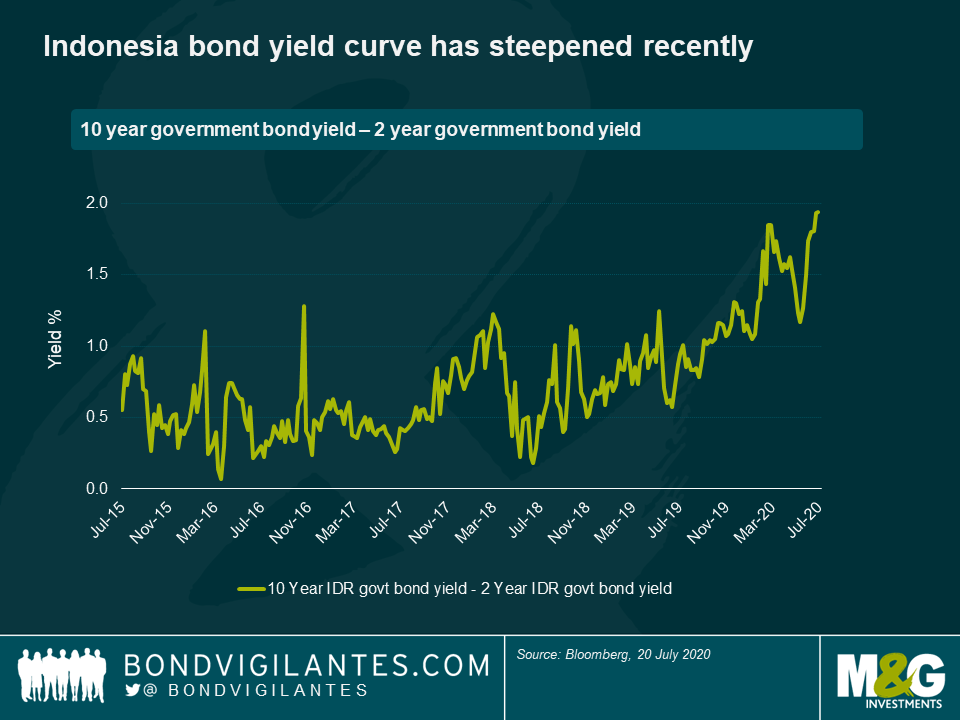

At a 7% yield, Indonesian government bonds are therefore attractive from a pure carry perspective, especially when compared with other investment grade local currency bonds in the JP Morgan GBI EM index (though non-resident investors should keep in mind that they will be subject to a 20% withholding tax, which will reduce their returns). In addition, while most of the rate cuts for this year are probably now behind us, the announcement of the debt burden sharing scheme earlier this year has led to a steepening of the yield curve. This leaves ample room for investors to benefit from a potential flattening of the yield curve should, for example, the budget deficit and government bond supply ultimately be lower than currently anticipated.

As for the currency, given the high degree of foreign ownership of Indonesian government bonds (around 38% for local currency bonds according to Moody’s), it has always been and is likely to remain quite volatile. For the currency to appreciate materially from this point onwards, one would probably need to see a sustained improvement in global investor sentiment and a return of investor flows into EM local currency assets in general, or to Indonesia in particular.

This in itself is conditional on the speed of the economic recovery and any material progress made in overcoming the virus. While visibility in this area remains low in the short term, the new debt burden sharing plan gives Indonesian authorities greater ability to provide support to Indonesian households and corporations that need it the most.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox