Sustainable investors, it’s time to talk about Transition bonds

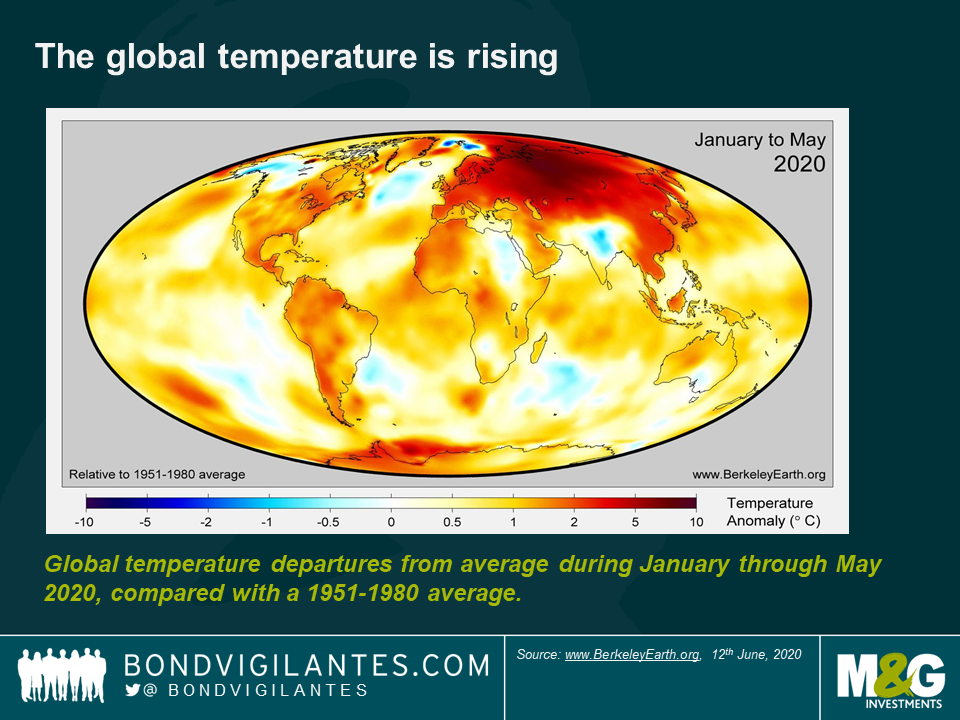

The EU has embarked on a mission to make Europe the first climate neutral continent by 2050. Rather unnoticed amongst COVID-19 headlines, the EU parliament approved the unified EU Green Classification System, also known as the EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities, on the 18th of June and turned it into law. A core pillar of the new regulation is to outline whether an economic activity qualifies as a green investment or not, so providing a clear industry threshold for green financing transactions. While the technical working group is still defining the screening criteria for certain segments of the market, it is clear that the eligibility criteria set are stringent. Undoubtedly, this is the right thing to do if we want to achieve the challenging goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

Global energy demand is set to continue to grow over the next 30 years, driven by a rising population and economic expansion. And while renewable solutions continue to see their market share increase, fossil fuels are still expected to make up at least 50% of the global energy mix in 2050 even under the most optimistic scenario, according to research from Barclays. The implication of this is that achieving a low-carbon world requires existing businesses, in particular brown industries, to decarbonize and mitigate climate risk.

The hurdle for carbon-intense businesses to issue green bonds remains high however. Such issuers fear coming to the market with a green bond and being criticized for it. It comes as no surprise that oil and gas names reflect a weight of only 0.47% in the BofA Merrill Lynch Green bond index, while their index weight in the BofA Merrill Lynch Global Corporate index is more than 8%. Despite this, I would argue that companies operating in brown industries are playing an important part in the energy transition we need. Many of them are sizable players, with large capital structures and research and development functions in place to accelerate the much-needed change. Just last month, Total bought a 51% stake in Seagreen 1, an estimated £3 billion offshore wind farm project in the North Sea. Not many players have the financial firepower and the ability to take on the construction risk for such a major project.

But what about activities that cannot be classified as green, yet play an important role in reducing a company’s greenhouse gas footprint? How can the investment industry encourage such behaviour for companies where the core of their business is not (yet) compatible with green financing?

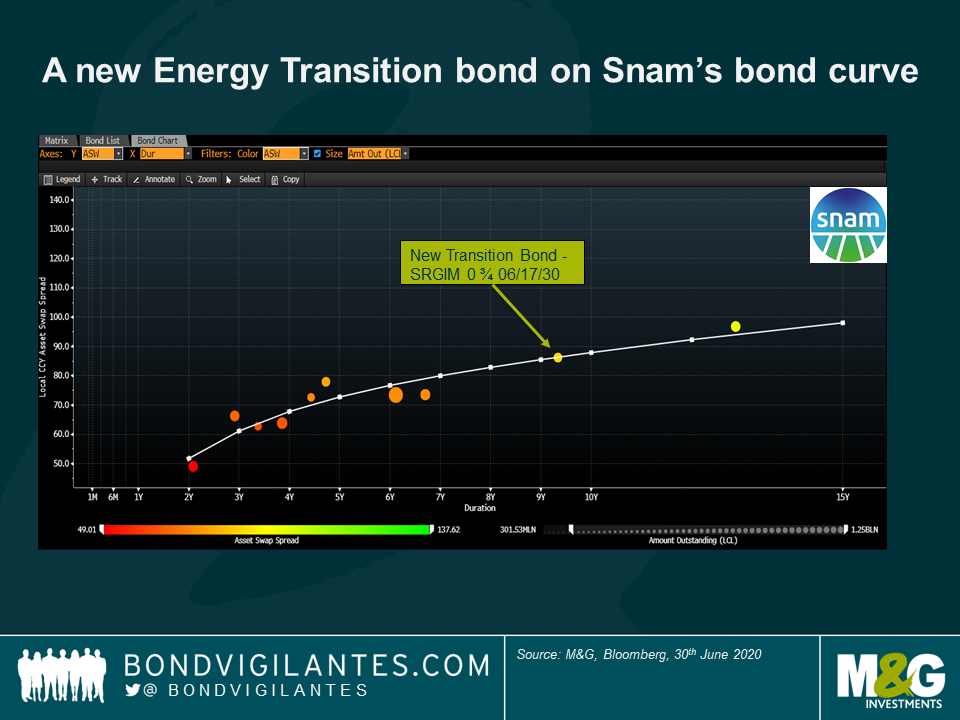

One possible solution to allow carbon-intense industries to receive funding from the sustainable investor base is Energy Transition bonds. These are bonds issued with the purpose of enabling a shift towards a greener business model. So far, this idea remains in its infancy, with only half a dozen such bonds launched. Last month, Italian gas transportation business Snam launched its first official Transition bond via a €500 million deal. The proceeds will be used to finance eligible projects related to energy transition as defined by the company’s Transition Bond Framework. For example, these proceeds can be tied to renewable energy projects by making gas pipes hydrogen ready, or to energy efficiency programmes by installing heaters with more efficient technologies to reduce methane emissions. The new deal was welcomed by bond investors, and was three times oversubscribed upon issuance.

Having said that, fixed income investors have already had their eyebrows raised in the early days of the Transition bonds market. In 2019, a beef producer issued a Transition bond with the aim of using those funds to buy cattle from suppliers that had agreed not to destroy more rainforest. Many would argue that the company shouldn’t be buying cattle coming from deforested areas in the first place.

This highlights the importance of having checks and balances in place, and is a call for industry-wide Transition bond standards. Market participants need a framework which outlines the eligibility criteria for the use of proceeds of such Transition bonds, including the minimum energy improvements that need to be achieved, how this is measured and reported, and the extent to which such a transaction must be linked to the issuer’s wider transition strategy. Only this will gain investors’ confidence and trust, and allow Transition bonds to become a more accepted and deeper market place. The EU taxonomy will provide some valuable signposts here to help measure whether a company’s planned use of funds is good enough to qualify as a Transition bond. If done rightly, Transition bonds can offer an important additional asset class for issuers alongside Green bonds, and with that help to prevent greenwashing in the green bond market.

With the right framework in place, energy Transition bonds could be the next evolution in allocating capital towards a low-carbon economy, close an important gap and help mobilize more assets to tackle climate change. Issuers can get better access to an increasing sustainable investor base, while bond investors would see their opportunity set increase substantially, all leading to a greater impact in mitigating climate risk. A win for bond investors, issuers and the planet alike.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox