In a QE adjusted world, bond indices look very different

Investing in public securities, whether equity or debt, is driven by two primary desires; firstly a need to save for the future, and secondly the requirement to see these savings grow. This results in a need for investors to pursue low risk and high growth investments. In order to understand these risks, assets get categorised based on their potential and historic risk characteristics. Broadly speaking, assets such as bonds are generally seen as defensive, while equities are viewed as more speculative. In order to break the understanding of investment characteristics down further, subsets of investments are produced, and therefore indices have logically evolved to show the performance of these subsets. Indices have now become a significant way for investors to gain investment exposure to asset classes via index funds. This all works well if the publicly available investment universe is well defined. But is it?

When constructing an index, the providers look to construct these using easily understandable and transparent rules. One rule is to ensure that the index reflects the publicly available free float of investment securities. This rule is in place so that distortions do not occur. For example, if there was a large stake in a company that was not free to trade, but the company’s weighting was based on all stock outstanding, then it would overstate the amount of publicly available investment securities.

This is the case for the current plans of the Saudi Aramco listing. The index providers will reduce the weight in the index to the actual free float level, which is a small percentage of the total equity outstanding to avoid distortions. Stating this plainly: if you do not adjust the free float, the index will not represent the truly available securities. Index tracker funds would then drive the price of the limited free float securities (i.e. the actual amount available to buy) higher as they try to get up to the “weight” shown at the index level.

Why does this matter? The monetary response to the financial crisis has been both conventional (via interest rates) and unconventional (via quantitative easing). The latter involves the purchasing of government debt by central banks, in order to print money, drive the term profile of interest rates lower, and increase confidence. This is designed to remove government debt from the public arena, and by definition reduces the free float of available securities. These holdings are not cancelled, but they are not available to be invested in (they are held on central bank balance sheets). Even index providers recognise this could be a potential problem.

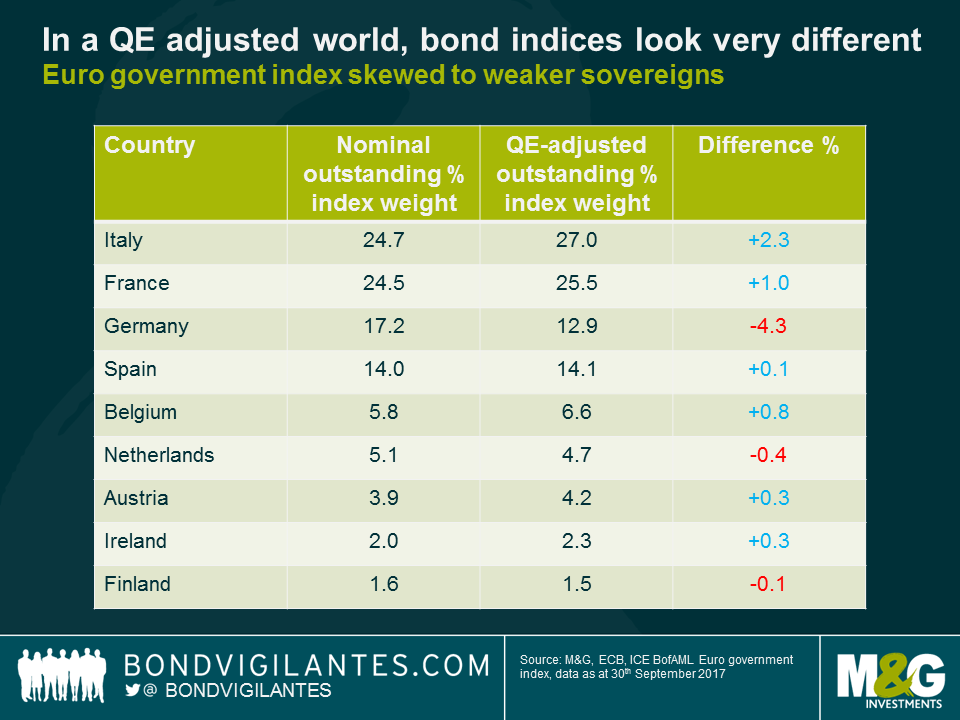

What would the world bond indices look like if they treated bonds purchased via quantitative easing programmes in the – what I believe to be, appropriate – manner described? As a market which is currently being distorted by central bank QE, the Euro government bond market is a sensible place to assess this. Looking at the ICE Bank of America Merrill Lynch Euro government bond index, the constituents are capitalisation weighted, based on the amount outstanding. With ongoing QE however, this no longer equates to the actual amount that’s available to buy. So making a point in time adjustment for ECB holdings of government debt and reweighting the index accordingly, the composition of the index changes.

In a QE adjusted world, bond indices look very different, with the Euro government bond index in particular skewed towards weaker sovereigns. Indeed, what’s immediately apparent is the increase in the weight of lower rated sovereigns such as Italy, at the expense of AAA rated Germany. German government debt moves from being the third largest holding (17.2%) to the fourth largest (12.9%) in the newly adjusted index. Since the ECB implements QE by buying government debt in line with the capital key (calculated according to the size of the member state in terms of population and GDP) German government debt represents over 20% of all cumulative QE holdings, reducing the index free-float quite significantly.

QE bond buying has important implications for funds which are tracking an index. If the index weights don’t reflect reality, then tracker and exchange traded funds are chasing increasingly scarce securities, driving up prices, in an attempt to recreate a false investment universe. Index tracking funds and ETFs may be distorting the price of securities that are over-represented in the indices but under-represented in the real investable universe.

There are two main investment implications from this analysis. Firstly, should the index providers alter the way they construct indices to reflect central banks asset purchases? Secondly, has QE resulted in excessive performance of lower debt outstanding (higher quality) sovereign issuers in the Eurozone, and elsewhere? QE is designed to drive bond yields lower, though the construction of indices in their current form and funds that are benchmarked against these indices has contributed to exaggerating this process. This may be yet another unintended consequence of central banks entering into the marketplace for debt securities. In the extreme, will the eventual suspension and reversal of QE result in weaker rated sovereign bonds outperforming their higher rated peers as the distortion is removed?

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox