Is UK austerity over? Cue the Autumn budget

This week’s Budget and Bank of England meetings may shed some light on a key question for investors and millions of taxpayers: After eight years of fiscal tightening, is austerity over and will the economic burden shift from monetary to fiscal policy? I wouldn’t hold my breath – something which may cheer gilt investors, at least for now. Let’s see why:

In her recent Conservative Party conference speech, Prime Minister Theresa May suggested that the UK is nearing the end of austerity, leading to certain spending optimism ahead of this year’s Budget. After all, Chancellor Philip Hammond does have a few things in his favour: higher receipts and lower expenditure this fiscal year means that government borrowing is expected to come in approximately £5-6bn lower than the Spring Statement forecast in March (which is likely to be met by reduced gilt issuance – more on this later). The consensus also expects borrowing to fall further in the next fiscal year, which could return the UK to pre-2007-08 crisis levels.

Though this all sounds positive, a recent Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) Green Budget conference painted a less rosy picture, especially with regards to UK public sector net debt, which is still high despite it falling slowly. Debt is still higher than pre-crisis levels and with growth expected to remain sluggish (forecasts are of 1.5% per year from 2017-23, compared to a pre-crisis average of 2.7%), the UK’s debt to GDP ratio will remain elevated.

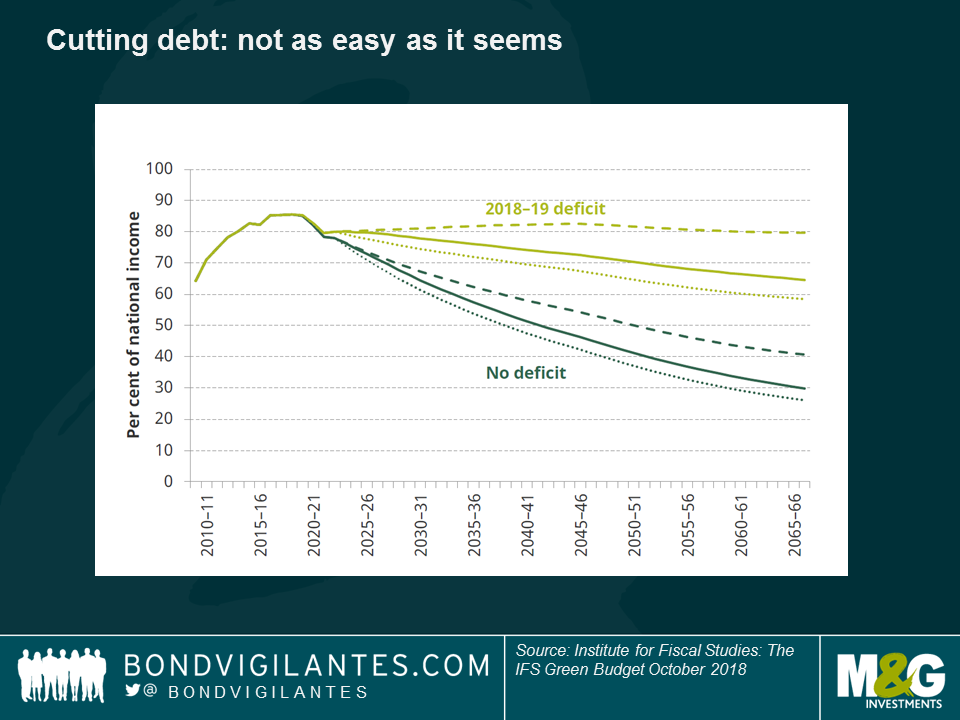

Despite the Chancellor’s savings, the high level of debt (currently approximately 85% of GDP) is still a concern, as this reduces the fiscal wiggle-room in the event of a downturn. In the chart below, the IFS shows the implications for debt going forward: maintaining a deficit of 1.8% of national income would see public sector net debt fall so slowly over time that even by 2040, it would still be above 70% of national income. Eliminating the deficit entirely would see this fall faster, but is this a realistic scenario? For a start, both scenarios assume growth will be smooth.

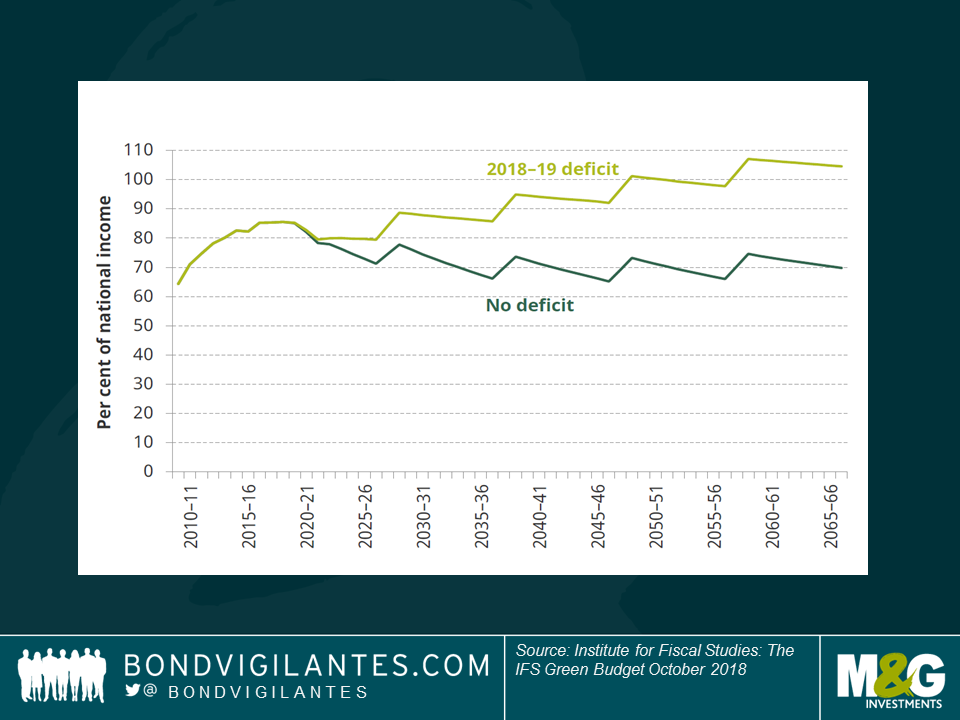

A closer look depicts an even gloomier scenario: as seen in the second chart, factoring in the impact of recessions, the IFS finds that even if the Government eliminate the deficit, from 2021-2066 debt as a % of national income will still exceed 2010 levels in each scenario.

Eliminating the deficit in itself remains a challenge, but there are additional reasons to be bearish. The Government has made pre-commitments of lifting the public sector pay cap and an additional £20bn in spending on the NHS will cost up to 1% of GDP by 2022/23. Where’s the funding going to come from? Cue the Autumn budget. However, given the Conservative Party’s manifesto to rule out any changes to the rate of VAT, income tax or national insurance (which equates to approximately of 60% tax revenues), it really is unclear to me how the UK can reduce debt.

I tend to think about the economy in terms of the components of aggregate demand (i.e. consumption, investment, government and net exports). I’ve been wary about consumers being able to prop up the UK economy (the savings rate is at multi-year lows, plus the strain on real wage growth is a concern) and business investment sits under a cloud of trade-links uncertainty. On the net exports front, the UK has seen a boost to exports from the currency depreciation, but imports remain elevated as it takes time for the substitution effect to kick in. As if I didn’t have enough reasons to be bearish on the UK economy (and I have intentionally avoided the topic of Brexit uncertainty!), the state of the government finances doesn’t fill me with much glee either.

What are the implications for UK government bonds? The reduction in borrowing (and therefore issuance) this year should be beneficial for gilt investors, but the degree of uncertainty regarding how the government will fund the extra planned spending may throw a spanner in the works. Any downwards revisions to borrowing in future years would reduce gilt supply and mostly likely lead to a knee-jerk reaction, with gilts rallying. This, however, might be short lived, as – to my mind – politics, not economics, is likely to remain the bigger driving force of yields in the near term.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox