Emerging market bond covenants: the devil is in the details

Since the beginning of the year, a few primary market deals have again raised concern about the gradual weakening of bondholder protection in emerging market corporate bonds.

When it comes to bond documentation, the devil is in the details. Offering memorandums are often in excess of 500 pages – the ones with over a thousand pages are viewed with a healthy degree of caution by the bond community – and sometimes only a few sentences/words make bondholders’ protection weaker and hence may change the economics of an investment. While there is some standardisation in terms and conditions in the high yield world, investors still have to do their homework. Here’s why, in 3 recent examples:

- Equity Clawback: An EMEA corporate was looking to issue its first index eligible bond in order to refinance its existing debt and provide incremental liquidity. As part of the research process, our analyst considered the detailed terms and conditions of the bond. They identified that the economics of the bond were negatively impacted by the inclusion of off-market equity claw language, whereby the issuer could redeem 35% of the bond at 101% in the event of a public IPO or private equity injection. In our experience, we believe that Par (or 100%) plus the coupon of the bond is the norm amongst other emerging market high yield issuers and this would offer investors materially better economic returns in the event of an equity raise by the company. Consequently, we raised the issue with both the company and the advisory banks and suggested that they amend the terms to better support investor interest in the initial capital raise and secondary trading of the bond. The bond terms were subsequently amended to reflect our concerns and improves potential bond investor economics.

- Debt Incurrence Test and Leverage Calculation: The contractual ability of a corporate to incur new debt based on a leverage (gross/net debt to EBITDA) metric. Sadly, a market trend has emerged that can flatter and/or create inconsistent leverage definitions. EBITDA is too often proposed being calculated on an IFRS 16 basis (which tends to increase EBITDA by adding back lease costs) while debt is calculated on a non-IFRS 16 basis (which tends to reduce debt by excluding lease liabilities). Therefore, leverage metrics tend to be lower and the issuer’s ability to incur more debt increases. We engaged on that topic too with the aforementioned corporate, suggesting consistency (IFRS 16 or no IFRS 16 on both numerator and denominator) but in this instance were unsuccessful in having the terms changed. This problem is also seen in Latin American deals where we continue to push issuers and advisory banks to propose a consistent leverage definition in both marketing materials and underlying bond documentation.

- Change of Control (CoC): Bondholders’ right to put the bonds (read: require early repayment), usually at 101%, in the event of a change in ownership. A decade ago, most CoC clauses in bond documentation were standard in the emerging market high-yield segment: initial ownership dropped to below 50% (or any other level set) and the CoC clause was triggered. Then, advisory banks started to be creative with an additional feature: the credit rating downgrade. The new CoC clause would only be triggered if (1) ownership dropped below a certain threshold and (2) the issuer’s credit rating was downgraded by one notch within a certain period of time. One recent Latam new issue had no less than a double-notch downgrade requirement for the CoC clause to be triggered (in addition to a carve out of any CoC protection in the event ownership changes at the holdco level). We pushed back on this and the response was that it was already embedded in previous bonds so it was retained for consistency.

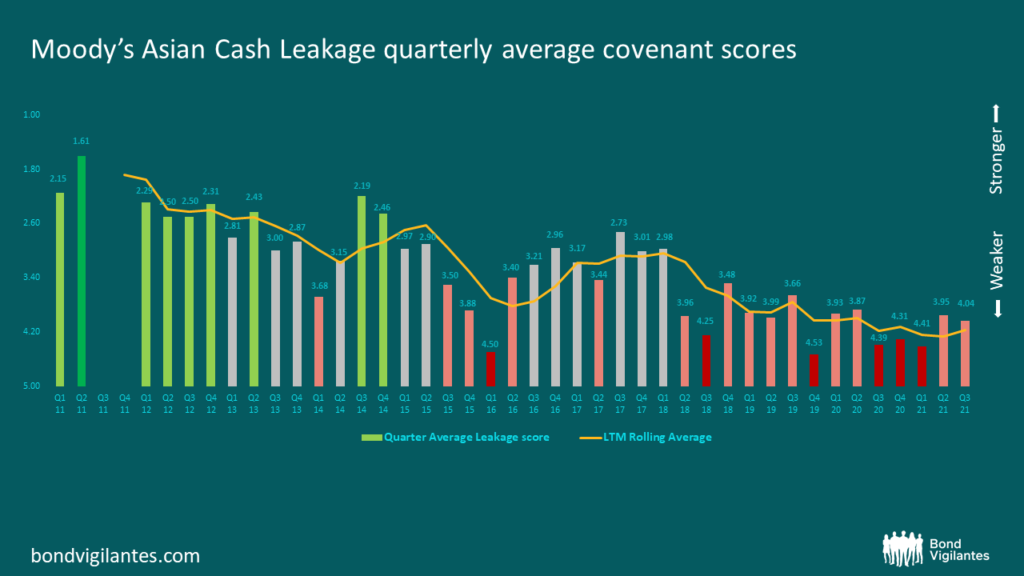

There are many more examples, e.g. early redemption structures or the inclusion/exclusion of FX losses in net income for the calculation of restricted payments (particularly important for emerging market bond issuers). Some areas of the market are much weaker than others. China high yield property developers have had appalling and deteriorating bond covenants for some time. Their very large, permitted investment carve-outs have enabled them to increase joint venture and associate’s investments – contributing to the lack of transparency about off-balance sheet items and cash leakage to unrestricted entities outside the restricted group (see chart). The debt incurrence ability of Chinese property developers has also been facilitated by the fact that (1) it is not based on a debt leverage metric and (2) the fixed charge coverage ratio (often EBITDA to interest) condition was getting increasingly aggressive (i.e., lower) over the years. Some property developers simply don’t have restricted payments, and others no debt incurrence conditions whatsoever (aka high-yield lite deals).

With China property now under immense stress and the rest of emerging market corporate bonds facing a lukewarm primary market at the start of 2022, perhaps this is a chance for the asset management industry to ensure – through engagement with issuers and advising banks – that covenants do not weaken further from here, and actually improve in some areas of the market. The more bond investors make their order conditional to bond document changes, the more likely terms and conditions will be amended to the benefit of bondholders.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.