Himalaya-high spreads: which emerging market sovereigns can acclimatise?

When mountaineers climb above 8,000 meters, they are considered to be in the death zone. At such high altitude, there is not enough oxygen. Their bodies experience huge stress until they descend to a safer elevation.

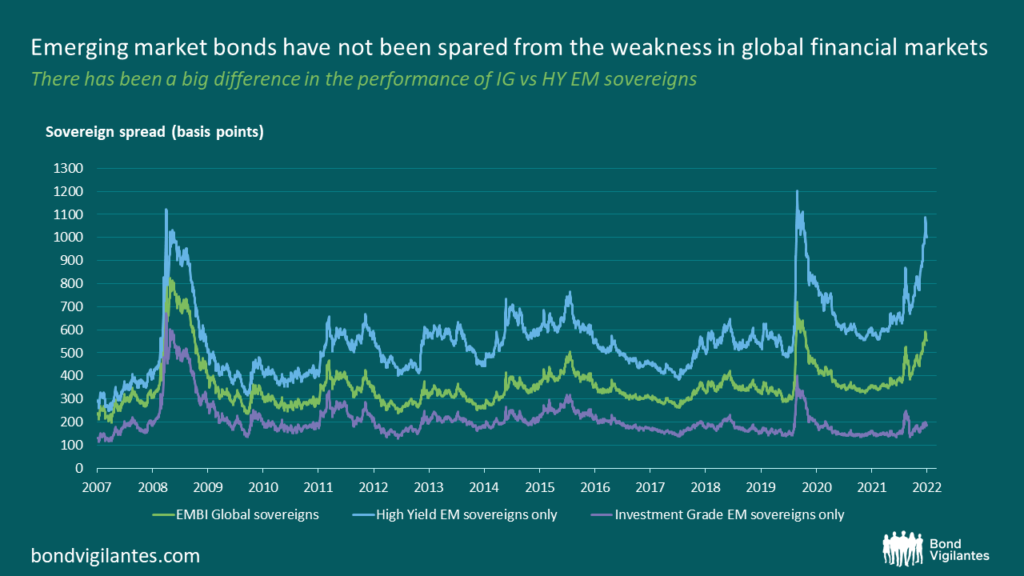

High yield emerging market sovereign bond yields have ascended in 2022 while global monetary conditions tightened, recession risks reverberated, the US dollar strengthened and widespread investor risk aversion took hold. With non-investment grade sovereign spreads recording historic highs at over 1,000 basis points, the eurobond market has recently been closed to most high yield sovereigns. And, like mountaineers, they are suffering from altitude sickness.

Acute mountain sickness

The highest mountain summits are harsh places to be, although some climbers do better at altitude than others. Investment grade emerging markets have become fitter, stronger and more robust over the past two decades: borrowing at home, building up reserves and keeping their deficits in check.

A big part of the global inflation problem comes from higher global prices for food and energy, which was exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In this environment, countries exporting oil and gas have fared better. Flush with petrodollars, their economies have thrived, with less need to issue bonds. Where the surplus is largest, oil exporters have reduced their debt in 2022 (for example, Oman was able to buy back past debt at low prices). Others have been able to step up their investments abroad, helping other countries solve liquidity issues (for example, the Gulf economies have increased their deposits in Egypt and Pakistan).

Conversely, at the weaker end of the spectrum are high yield sovereigns that import commodities, which struggle most when energy and food prices spike. Such countries are downgrading their growth forecasts for 2022 while experiencing big jumps in inflation. But, those most in danger are high yield sovereigns that were counting on markets being open to refinance maturing bonds.

Sri Lanka had debt problems brewing over the past five years that were exacerbated by the pandemic. With foreign exchange reserves depleted, they defaulted on their eurobond debt in May 2022. Sri Lanka’s default, sour markets and a weaker global macro backdrop have prompted concerns over whether more emerging market defaults might follow. To answer this question, we need to go country-by-country and carefully assess their refinancing risks.

Sitting out the storm

Thankfully, most high yield sovereigns do not have large amounts of eurobonds maturing in 2022 and 2023, so they can get by even without market access. Those with eurobonds which need refinancing over the next 18 months will need a plan B. They can seek syndicated loans to bridge the financing gaps, or use their foreign exchange reserves – akin to putting up tents and sitting out the bad weather.

Sovereigns that have climbed with lower supplies will need to radio in a rescue from the IMF, multilateral banks or bilateral climbing partners – although that helicopter might only be dispatched if reforms plans are set out and debt stocks are deemed sustainable.

External public debt is not always the main debt pressure. For some countries, there are bigger near-term struggles with domestic public debt burdens (as seen in Ghana), hard currency corporate debt (as seen in Turkey) or debts to the IMF and multilateral banks (as seen in Argentina). If these debts are not rolled, then their ability to service the eurobonds would also be impaired.

These near-term survival strategies suggest that an emerging markets crisis of a 1980s size is unlikely in 2022 or 2023. However, further pressures could mount if market conditions do not improve ahead of higher high yield sovereign bond maturities from 2024.

To the plains or plateau?

When past bouts of Himalaya-high spreads are analysed, the good news is that they have safely descended (for example, around the time of the global financial crisis and when Covid-19 became a pandemic in March 2020). This cycle could turn out to be similar, if advanced economy recession clouds pass, rates volatility calms and the flight to safety begins to reverse.

Whatever its timing, it is unlikely to be a straightforward descent from the summit. Rather than returning to the plains, there could be a new slog across a plateau – one made more difficult by heavier loads, as most high yield sovereigns have added substantially to their public debt stock since 2019.

On such a plateau, there would be far more oxygen than at 8,000 meters, so altitude sickness would ease. But the air would still be thin. Here we should be thinking through how scenarios of a US 10-year treasury yield at 3% or 4% might play out, versus the average of 2.4% experienced between 2010 and 2019. Plans for longer maturity eurobonds (30-years or more) that became a common feature for the frontier between 2017 and 2019 might end up buried deep in a crevasse for lower-rated countries. And those sovereigns that have already struggled with shorter maturities when US treasuries were lower, would find the market more challenging than before.

Despite most emerging market bonds screening cheap at current spreads, there is a crucial need for country-by-country analysis. For many non-investment grade sovereigns, the descent from the summit back to market access will be tricky. Much effort will be needed to acclimatise.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.