The Latam Pink Tide: takeaway from a field trip

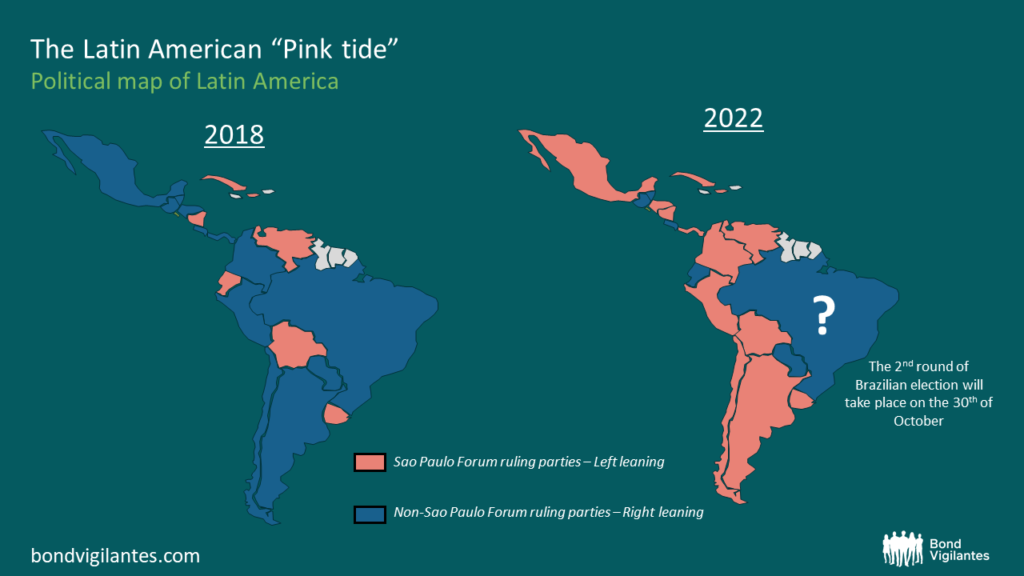

The political landscape in Latin America over the past 18 months – from Boric in Chile to Petro in Colombia more recently – has changed to varying degrees but only in one direction: to the left. Some have coined the change the pink tide, others the pink wave. I like the image of a pink tide, slower but mightier than a wave. This pink tide may expand in a couple of weeks if Brazil’s presidential election sees Lula winning, in what is expected to be a tight second round against incumbent Bolsonaro. I am just back from a two-week research trip in Latam (Mexico, Chile, Peru and Colombia) where I met with several corporate bond issuers and local investors and I came back with a mixed view. On the one hand, policy risk has materially increased and the business environment has changed in some countries. On the other hand, I find value in Latam corporate bonds in US dollar relative to other regions of emerging market debt.

Source: M&G, Wikipedia Oct 2022, countries with members of Sao Paulo Forum ruling parties (Pink) and non-Sao Paulo Forum ruling parties (blue)

From a fundamental standpoint, businesses in the region are in decent shape even though policy risk has already impacted some of them. Utilities have seen credit metrics deteriorating recently, but the starting point is strong in terms of balance sheets. The oil and gas industry benefits from high oil prices but is vulnerable to tax and environmental regulation, notably in Colombia. The demand outlook and market imbalance for key metal-based commodities should provide support for miners in general but Chinese GDP – as a key demand driver – remains a question mark. In the retail space, profits have been impacted by margin erosion due to input cost inflation but top-line numbers continue to stay strong, sustained by consumption. Refinancing risk is moderate and Latam HY default rates are expected to be low-2% in 2022, and moderately higher next year. In terms of valuation, Latin American corporate bonds in US dollar offer a spread of 480bps over US Treasuries – a wide level not seen in 6 years (excluding the pandemic). In 2016, default risk was much higher after the region got caught in a wide-spread corruption scandal originating in Brazil and credit metrics were weaker too. Political risk has increased in many countries in the region but one may argue that the increases in geopolitical risk elsewhere – e.g. Eastern Europe, US-China – are more lasting and worrying changes for asset prices in the medium to long term.

Here is my takeaway on the four countries I visited, how the business environment has changed (or not) with the pink tide, and the implications for bond investors.

Mexico

- Probably where the macro outlook is the most stable. Leftist president Lopez Obrador (“AMLO”) is very popular in the country – notably thanks to its elderly population’s pensions and the perceived fight against corruption – whilst not so popular with the business community. Strong consumption is driving the economy and most companies I met have strong top-line growth. However, higher input cost has had an impact on businesses that are unable to pass through the entire cost inflation to end clients (margin erosion) or those which are prevented do so by regulation in the energy sector (working capital needs are elevated on lagged payments of subsidies). The Russia/Ukraine conflict in Europe and the US-China geopolitical tensions are all seen to benefit Mexico in the way of US nearshoring.

- Inflation, like elsewhere, is a question mark. The government expects 3.2% next year but this is well below economist forecasts of mid-4. Banxico continues to keep a high premium over US rates and the Mexican Peso has been stable and outperforming many other peer currencies this year. The current administration, despite its left-leaning rhetoric, is actually praised by investors for its fiscal sustainability. Both deficits and debt levels are low, and the government’s 2023 budget proposal is unlikely to put fiscal stability at risk.

- State-owned Pemex continues to be the “elephant in the room” with tight liquidity and an insolvent balance sheet that requires a constant lifeline from the government, despite this year’s elevated oil prices. Local investors think the AMLO administration will provide support at any cost. Going into the next presidential election in 2024, there is a wide expectation that the left (Morena party) will stay in power and back Pemex whatever it takes.

Chile

- For decades, everyone forgot that Chile was located in South America. The business district of Santiago does look modern, but other areas of the city nonetheless still have visible signs of the 2019 unrest in which over a million people protested against social inequality. The election of a young (now 36 year-old) left-wing President in 2021, Gabriel Boric, paved the way for a referendum to change the 40-year-old Chilean Constitution. Too controversial, the new Constitution was rejected in September 2022 by over 60% of voters. Since then, the leftist government has lost a lot of political capital and locals expect another – more sensible – Constitution should be presented within 24 months.

- Chile’s economy relies much on the mining industry and most of the key players I met reiterated the importance of China for copper (50% of global demand). Marginal copper demand should also come from India and Asia ex-China in the future, driven by electric vehicles and renewables. The outlook is even brighter for lithium (the country has the world’s largest reserves) which displays an impressive demand outlook (2021 was +50% yoy; YTD 2022 +40% yoy; min 25% per year until 2025) on the back of electric vehicle sales in China and Europe. Both copper and lithium miners are facing risk of increased royalties with the proposed tax reform.

- The non-mining sectors have experienced various trends. In retail, margins have been under pressure due to input cost inflation, but businesses are generally solid with strong balance sheets, and they benefited from both higher spending from early pension withdrawals and a strong rebound in consumption after Covid. The telecom sector is unique in Latam in the sense that it is the most disrupted in the region – too many players and an inability to increase prices have resulted in weaker credit profiles over time (e.g. VTR). Utilities are impacted by the fact that Chile is a net oil and gas importer and most companies have shown working capital pressure with impacts on credit metrics.

Peru

- Lima is not Santiago. Roads are noisier, streets are busier, and Lima felt overall livelier (day and night). Politics too. As of late August, in average a new minister has been named every six days since ex-teacher and unionist Pedro Castillo became president in July 2021. Castillo’s reputation varies from “poor” to “bad” in the business community. More surprising though, it seems that the population blames the president for high inflation. Although higher prices impact most countries around the world, food is a very large item in the inflation basket in Peru and the weak Peruvian sol is only amplifying the effect.

- The mining sector (10% of GDP and 60% of exports) is carefully monitoring upcoming policy impacts. For instance, the government is trying to force miners to put on payroll most of their contractors (a measure that happened in Mexico last year and had a small impact) and royalties will go up in copper mining. Similarly to Chile, miners have seen cost inflation across the board in Q2: explosives, transportation, steel. However, unlike Chile, electricity prices are competitive because Peru produces (and exports) gas. In the third quarter, inflation has seen a slowdown.

- I also had the opportunity to meet with local Peruvian pension funds. The mood was rather bleak. Partly because pension withdrawals over the past couple of years (as a source of income for households during the pandemic) halved pension funds’ asset under management. But also because there was a general sense of resignation about Peru’s political outlook. Castillo has faced two impeachment proceedings since he took office – both failed, but corruption allegations continue, and political stability is never granted.

Colombia

- The most recent addition on the Latam pink map (before Lula in Brazil?), former guerrilla fighter Gustavo Petro became Colombia’s new president in June 2022. Petro is a more seasoned politician than Castillo in Peru and more experienced than Boric in Chile. He appointed in August a market-friendly Finance Minister (José Antonio Ocampo) and quickly introduced an ambitious (and ever-changing) tax reform proposal with a new oil and gas export tax (allegedly abandoned), the non-deductibility of royalties, a corporate income tax surcharge of 10% (increased from the 5% proposed at the time of my trip) for oil and gas and financial institutions, as well as higher income tax on wages of more than 10 times the minimum wage, amongst other measures.

- The oil and gas sector is at the centre stage of Petro’s proposal for a couple of reasons. First, Colombia is a net oil exporter and majority state-owned company Ecopetrol accounts for 12% of the country’s revenue. Increasing taxes on the sector in the current oil price environment is an effective way to raise budget revenues. Second, there is also an ideological argument. Petro campaigned for a sustainable transition of the Metals and Mining and Oil and Gas industries. For that purpose, he made a very controversial appointment with Irene Vélez as Minister of Mining and Energy: a philosopher and doctor in political geography, she has close to no experience in mining and energy. Following the announcement by the government of restriction on fracking and limitations on new concessions or permits for oil explorations, credit spreads of oil and gas issuers (including Ecopetrol) widened significantly.

- I also met a large utility firm in Bogota, and they were not spared either by policy change. The government recently changed tariffs to Consumer Price Index (CPI) from Producer Price Index (PPI) and the previous government had already prevented the Foreign Exchange market pass through for transmission assets, which is a problem for utilities that had funded their assets with long-term USD bonds on the assumption that their revenues were USD-linked.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.