So long, and thanks for all the fish (and Oil)

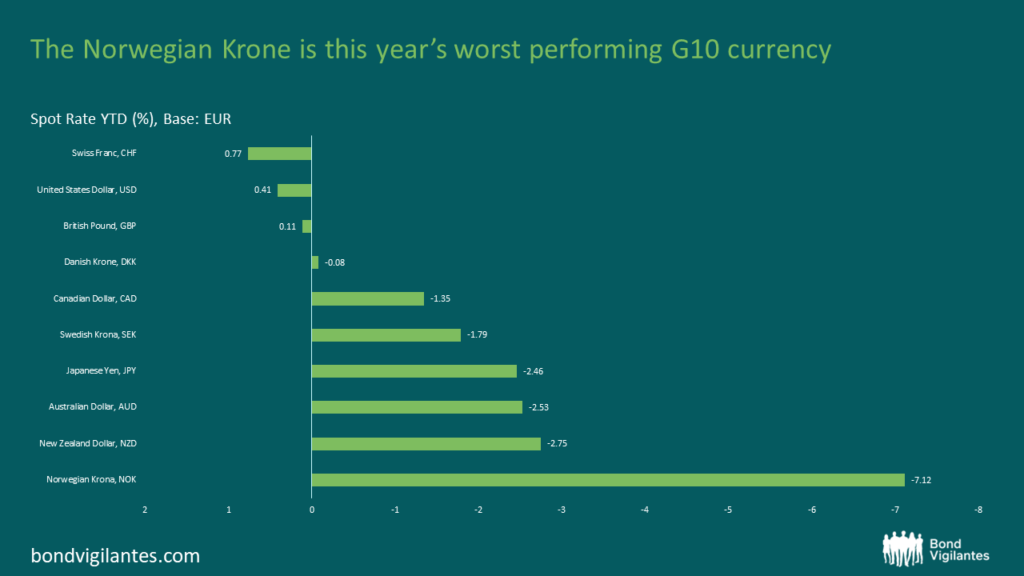

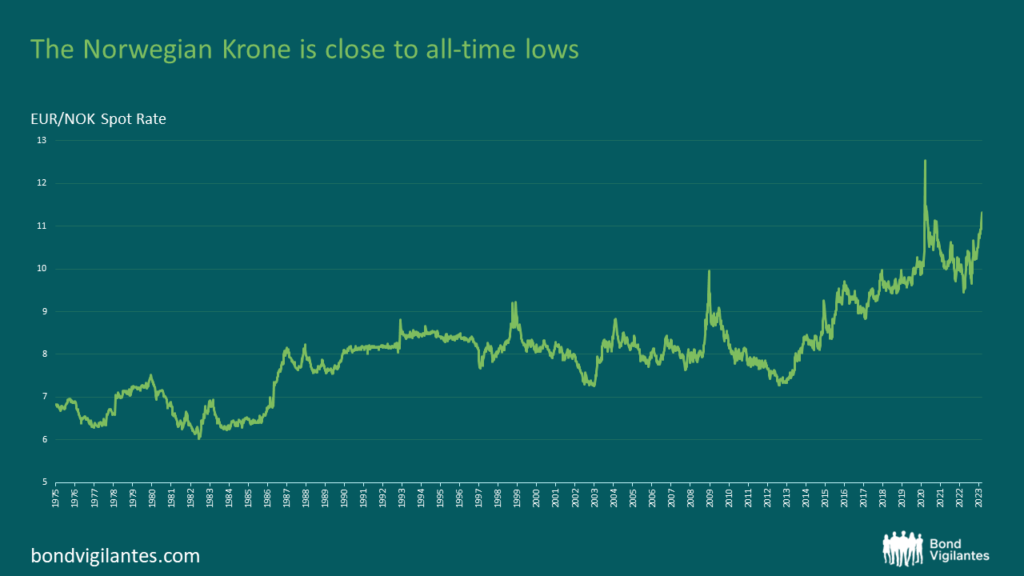

Investors have abandoned Norway’s NOK. The NOK is this year’s worst-performing G10 currency and is flirting with its all-time lows; it’s pretty much there if you strip out the COVID extremes.

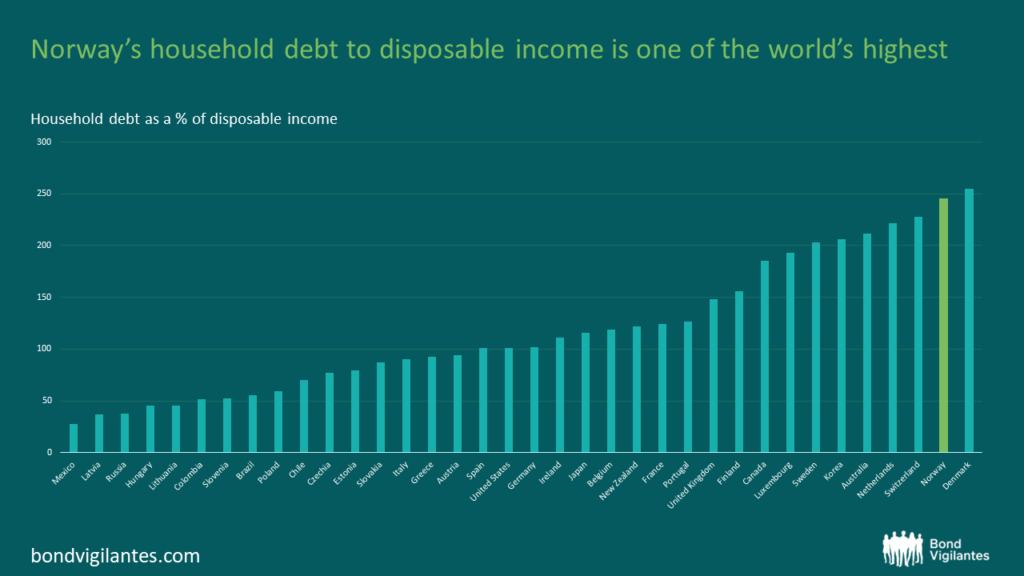

Some weakness is understandable. Household debt as a % of disposable income (chart below) is one of the highest in the world. Norway, like Sweden, is heavily exposed to variable rates; any changes should slow consumption growth as household debt-servicing costs increase.

Countries in this situation find themselves in a bind. Continue to raise rates to combat inflation but risk a significant contraction in GDP; don’t raise rates, or, at least by less than the rest of the pack, and the exchange rate continues to fall, and inflation persists. Europe has also played catch up in terms of interest rate differentials as the ECB has embarked on an aggressive rate hiking cycle, further contributing to a weak NOK. The NOK is also considered a high-beta European currency and tends to suffer in times of stress.

The valuation now feels too stretched from its fundamental value and looks attractive.

Norway’s problems are not dissimilar to the rest of Europe: high inflation, tight labour markets with increasing wage settlements on the increase, high property prices, increasing interest rates, cost of living concerns etc.

With sticky inflation, Norway should be able to lean more hawkish and raise interest rates further, supporting the currency. The housing market will feel the squeeze; however, a 20% correction is warranted given the surge since the beginning of Covid. The Government is also able to support consumers if required but seems unnecessary as both goods and services consumption has held up well so far.

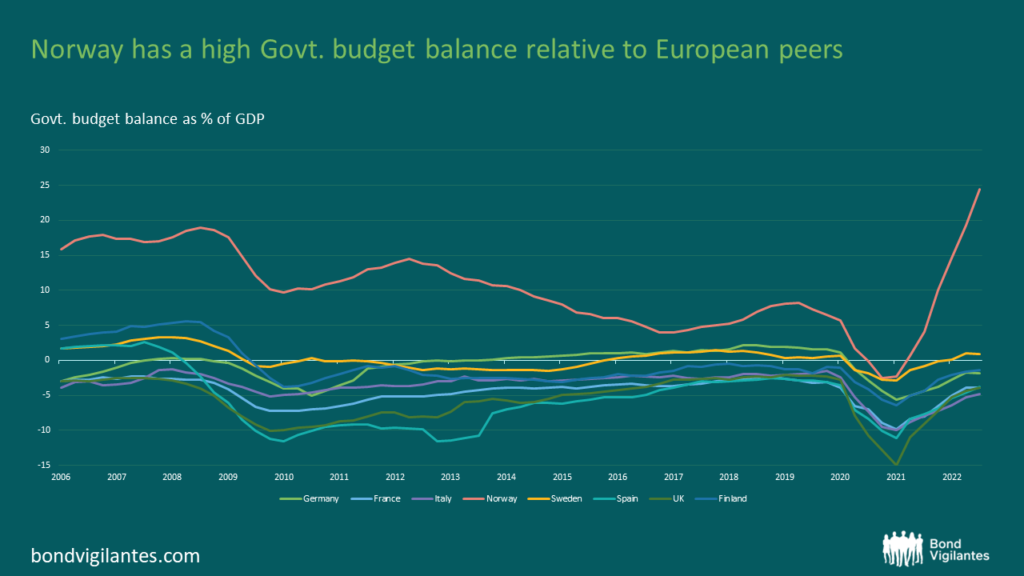

Norway is sitting pretty with pocket aces. The first is outstanding Government debt of 36% of GDP. The second is the country’s twin surplus, with its oil and natural gas exports boosted alongside the price increase due to geopolitical events. The current account balance of 30% of GDP and a fiscal surplus of 25% for 2022 should recede but will likely remain elevated and above that of its European peers.

So if the problems are the same across the board, wouldn’t you want to invest in a country with low debt, a twin surplus and an already cheap currency?

Also, the other side of the currency equation is not without its risks. There will always be the concern that European break-up fears will return. It might not be on anyone’s radar now, but cohesion is always stretched during economic hardship. The war in Ukraine might have strengthened resolve for the time being, but it is difficult to say. Break-up risks may return; it’s certainly a risk.

Norway’s position is the envy of Europe – a genuine AAA.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.