Cancel Culture – A New Monetary Phenomena

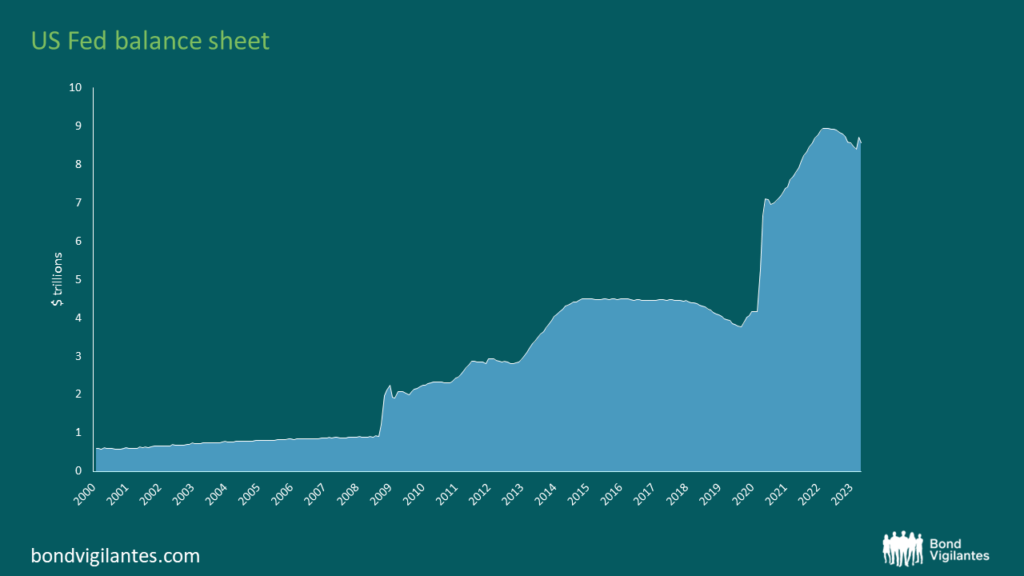

We have spent over 15 years talking about quantitative easing (QE) and quantitative tightening (QT). Each phase of QE has become increasingly more significant, resulting in a huge final dose of monetary creation in response to the COVID crisis. This money is now being cancelled.

To recap QE is the printing of money. Theoretically, this is expected to be inflationary. Increasing the supply of something will reduce its value, all else being equal. Traditionally this was implemented with old world technology: the printing press and then reversed in the furnace. It is now achieved electronically: money created from thin air at the magic press of a computer button, and cancelled in the same manner.

The original fears when this innovative measure was introduced were that the increase in the supply of money would have the understandable side effect of increasing inflation. This did not occur in the first phases of QE. Therefore, the policy became more acceptable. The link between the money supply and inflation appeared to be theoretical only, given the real world results. However, the empirical evidence of late would point to the opposite conclusion. Too much QE does result in inflation. I discussed this further in my previous September 2022 blog. The central banks are now tackling this inflation and they have been taking aggressive action to solve the problem. They have two prongs of attack: conventional rate hikes – which have been historically strong over the last year – and QT.

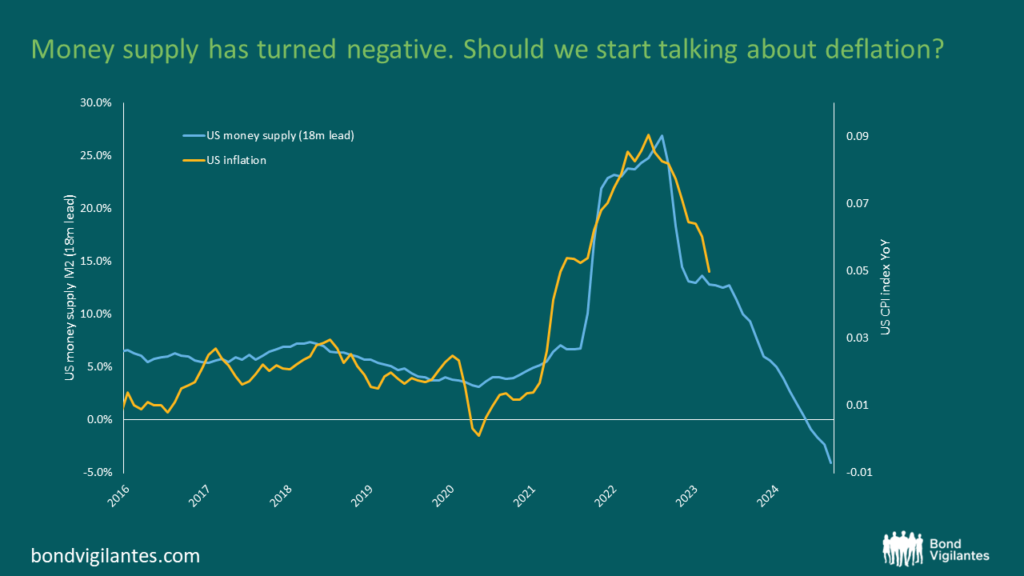

The charts below show the broad relationship between money supply growth and inflation. There is a historical observable link between the creation of money and inflation. This monetary lag of around 18 months is a constant feature of the economy and markets.

Source: Bloomberg, BLS, Federal Reserve, 31 March 2023

From the charts it is pretty clear that the recent inflationary surge is potentially a function of money supply growth. Strangely, this is something central bankers do not focus on. Maybe because of the data set they have from early QE? From a monetarist point of view this is a mistake, as espoused elegantly by Tim Congdon. I have a great deal of sympathy for his views. It seems strange that Central Bankers recognise that supply demand dynamics are important: a shortage of energy, labour and microchips are all inflationary, but they don’t seem to recognise that an abundance of printed money reduces its price – A.K.A. inflation!

The most interesting point on this chart is the degree of monetary cancellation: it is historically unprecedented. On a simple reading, this is hugely deflationary and suggests that inflation will reach new lows. The culture of cancelling money has not yet reached its zenith. We know that central banks are signalling that this process will continue and we can assume that money supply growth is likely to remain negative for some time. This is a new grand experiment.

Which is correct? Is money supply growth inflationary or not? One way of squaring the circle of early vs late QE would be to analyse where the printed money went. During early QE, it simply filled the bank vaults to make banks solvent against depositor runs, and paid for previous lending mistakes, refilling the reservoir due to the drying up of financial markets. The later stages of QE resulted in cash overflowing from banks into the real economy, and therefore brought about inflationary consequences. Is it the environment that QE is undertaken in that determines the inflationary outcome?

One way to maybe perceive this is to analyse the recent woes in regional US banks. Cancelling money through QT results in less money in the economy. Therefore, banks will have less deposits on aggregate. If this deposit drain is focused evenly across the system then the effects on each institution are minimal, but if that drain of potential reserves all comes out of one institution, then that bank will face problems. Printing money to provide liquidity and reserves to support the weak banks in the first stage of QE has been replaced with cancelling reserves via QT, challenging the weaker banks.

Most investors didn’t seem to be too worried about inflation 18 months ago when money supply reached a historical high. Now inflation is at the forefront of our minds, but money supply is negative. This cancel culture of quantitative tightening is a new monetary phenomenon. Should we be starting to think more about deflation than inflation next year?

‘inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than the output’ – Milton Friedman

Source: Federal Reserve, 26 April 2023

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.