Gabon’s debt-for-nature blue bond: a great try but did they get the conversion?

Gabon has recently issued a debut $500 million blue bond, arranged by Bank of America and the Nature Conservancy. Credit enhancements, including political risk insurance from US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) ensured the bond had an Aa2 rating from Moody’s, a level much higher than the sovereign’s Caa1/B credit rating.

These debt-for-nature deals are pitched as kill-two-birds-with-one-stone solutions, as they aim to conserve nature and lower debts. I think they also provide good branding for countries wanting to market their sustainability credentials to attract investment.

The Gabon blue bond is a successful outcome from a long-awaited transaction. Like other debt-for-nature deals I judge it in four ways: (i) nature directly conserved; (ii) sustainable brand building; (iii) debt risks reduced; and (iv) costs and complexity.

Gabon’s blue bond scores well on several fronts but less well on reducing debt risks. And don’t worry, despite the title, there won’t be many tenuous rugby analogies coming.

- Nature conservation: heroes in a half shell

Gabon’s blue bond, like recent transactions in Ecuador, Barbados and Belize, borrows money (at lower cost than usual) to finance conservation projects.

I have had several wonderful trips to Gabon (it’s hands down my favourite place for a biodiversity holiday). My thoughts are they could have gone blue or green in Gabon as its nature is pristine across with dense forests and stunning coastlines. A nature booster is that 91% of Gabon’s 2.3 million people live in urban areas.

This deal provides around $150 million for biodiversity protection and nature-based resilience initiatives, with a focus on national marine protected areas. My view is that the Nature Conservancy’s involvement in designing the conservation financial plumbing gives it credibility, increasing the chances the money will be spent well.

- Sustainable brand building: beyond oil credentials

Gabon’s ESG profile is pretty bad. It is completely dependent on oil exports (plus some manganese and timber) and scores very badly on governance measures. On the plus side, the country has decent income per capita (versus peers) and credible IMF-supported macroeconomic performance. So something is needed to turn investor attention to the idea that Gabon is more than a petrol station, has wonderful biodiversity, and has potential for non-resource growth. This blue bond really helps with that.

- Debt risks reduced?

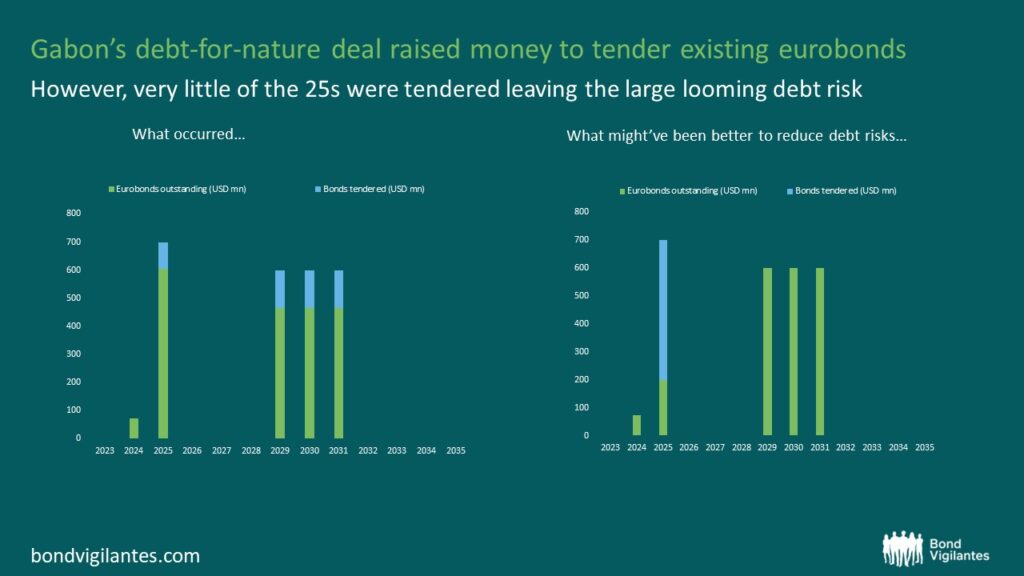

It’s this area where the deal falls a little short. A tender was announced on the 25s and the pair of 31s, financed by the new blue bond proceeds. However, the deal-makers accepted little of the 25s offered by investors (just $95 million leaving $605 million) while taking $405 million of the 31s pair out (leaving $1.4 billion). This is odd as the bullet payment in 2025 is the largest near-term debt risk in my opinion (as the 31s each amortise over 3 years). Note the government has already successfully reduced eurobond maturities in 2024 to just $73 million.

Before this deal Gabon was on the worry list for a large 2025 bullet eurobond maturity. This transaction offered a chance to eliminate this debt risk, but after this transaction that risk remains.

It is a puzzle why the 25s were not the main focus of the tender. Perhaps the reason was that the market price of the 25s was close to face value and the deal could show off a larger debt reduction (versus face value) by buying more of the 31s (that were trading at a larger discount). Most of the recent debt-for-nature deals have occurred where the sovereign’s bonds were trading at distressed levels versus peers, with large discounts achieved in the buybacks, although in Gabon this was not the case.

My other thoughts on reducing debt risks from these deals are two-fold. First, debt-for-nature deals were pitched in the 1980s as a means of converting existing hard currency debt into a local currency debt, so can we see this soon? Debt risks would be much reduced if the new loan were in local currency and not dollars. Secondly, I’d also like to see these deals also result in a small trust fund for improving debt management capacity. One of Gabon’s hurdles for lowering its borrowing costs is a low credit rating. The rating is low in part because of frequent mistakes with late debt payments, suggesting efforts are needed to improve cash and debt management.

Source: Bloomberg (August 2023).

- Costs and Complexity

The Aa2 blue bond matures in 2038 (with an average life 9.7 years) and was issued 200 basis points over US Treasuries. This is much cheaper than Gabon borrowing without credit enhancements (the Gabon 31 eurobonds currently have a yield of around 10 percent). Whether it might have been issued 20 basis point cheaper could be debated, but won’t be here. My thoughts on all new and non-standard issuance is that they need to be explained well to investors and communication by the deal makers needs to be really good. And like all issuance, market timing is a big factor in pricing.

One criticism of recent debt-for-nature deals has been the cost and the complexity. However, some of the issues have been resolved via better explanation of the deals (the Nature Conservancy notes on the Belize and Barbados transactions are really helpful). They typically come with a flow chart that helps demystify the links between the sovereign, the necessary SPVS, the credit enhancements, the flows of conservation money, and the fee-earning deal arrangers. So I wait for one of these explainers to judge the costs and complexity.

Conclusion

Gabon’s success with this blue bond is welcome and a real positive. But just like in rugby, it was a try scored out by the corner flag where the (debt) conversion, and extra points, were missed. Generally, I think the narrative on these transactions needs to be tweaked from maximising the reduction in debt levels, to maximising the reduction in refinancing risks.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.