ESG developments in Asian Banks

There is a strong argument that Asia holds the key to the future of our planet. Despite comprising just 22% of the Earth’s landmass, Asia’s 4.8 billion inhabitants account for 59% of the world’s population. While it is at the forefront of public consciousness for environmental reasons, with India and China in particular often associated with high emissions, its population density makes it a flashpoint for social issues too. With 153 people per square kilometre, it is three times more heavily populated than Africa (49) and even further ahead of Europe (33) and North America (28). If we add to the mix its position as the world’s factory – despite recent “near-shoring” trends – it becomes plain to see that the world as a whole cannot make serious progress on environmental or social issues without this continent’s full engagement. As financial agents of change, the region’s banks will be key to facilitating its transition policies. We have therefore saved the best for last as we conclude our series of discussions with global lenders on their ESG policies by looking at Asian banks (see here for previous articles on LatAm and GCC banks). Our findings are drawn from direct engagements with banks across the continent.

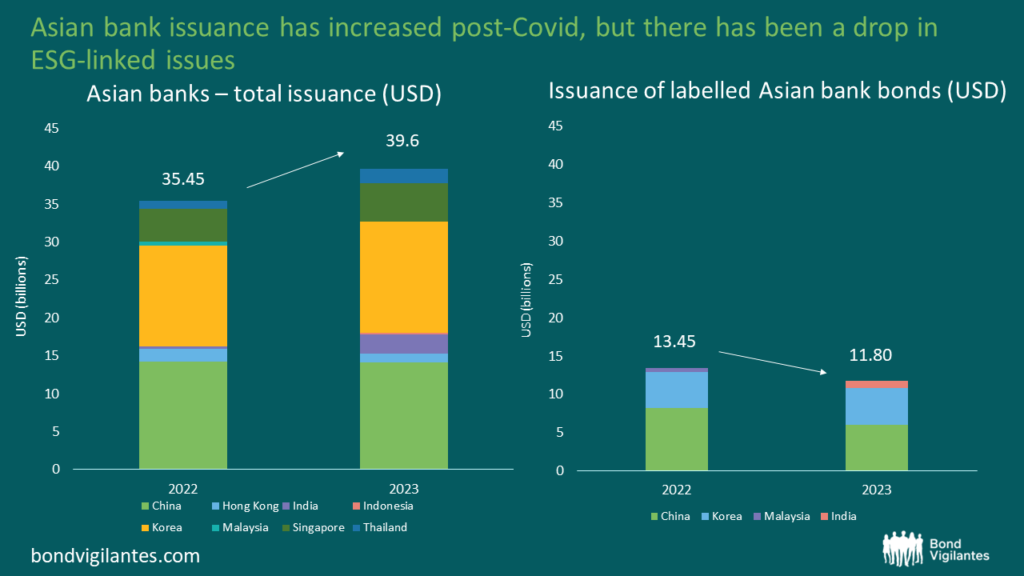

The results are a mixed bag, which is no surprise in a region which contains countries ranging from the very wealthy (Singapore/Korea) to developing (Indonesia/Thailand). The detailed comments below will show that Asian banks tend to have better developed social and governance policies than is the case in the environmental sphere. This is partly due to their starting position in a region where social issues have been higher on the agenda than environmental ones until relatively recently (unlike in LatAm) and partly due to a lack of green assets to invest in as there is no equivalent in Asia to, for instance, the GCC’s efforts to develop solar panels and green hydrogen technology at scale. But perhaps the greatest differentiating factor between Asia and other regions is a relative lack of investor interest in ESG. This means that the impetus to develop meaningful ESG policies comes from governments, regulators and bank management rather than the investor community. This lack of investor engagement contributed to differing progress across the region – banks in Singapore, Korea and Thailand score well, while India and Indonesia have a lot more work to do – and also explains why international labelled bond issuance has fallen year-on-year despite a rebound in economic activity post-Covid and an increase in bank issuance over the period (see charts).

Source: Bloomberg (November 2023) *Data 1 Jan – 31 Oct each year

Environmental:

- Environmental issues are a key priority for the region’s policymakers, so it is no surprise to see them reflected in banks’ lending policies. Most Asian countries have signed up to the Net Zero 2050 pledge (Indonesia is an outlier here with a 2060 commitment). However, the banks are at very different stages of implementing credible green lending policies. Countries with the strongest regulators, notably Singapore and Hong Kong, have made the most progress. Banks here have mandatory ESG screening for all but the smallest corporate loans, lists of prohibited sectors developed in conjunction with their regulators (typically referencing the property development, energy and power utility sectors) and targets for green loans and investments. These policies are drawn up with reference to the EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities, which is seen as the global gold standard for ESG. As is often the case, the growth of green lending portfolios is somewhat hindered by the lack of sufficient green assets to buy, though we expect this pool to grow over time and banks’ loan portfolios to change materially for the better over the next few years. Green loans typically make up 10-15% of banks’ portfolios.

- In other jurisdictions, notably India, Indonesia and China, things are less advanced. This is due not only to weaker regulation but also to weaker transparency and reporting. In Indonesia, for instance, environmentally friendly lending is not defined by the EU Taxonomy but by a weaker local equivalent, under which up to 30% of loan portfolios qualify as “green”, which is an improbably high number. Palm oil also remains an important export for Indonesia, which explains why weaker environmental definitions are needed. China is interesting because the regulatory impetus to develop green lending frameworks is minimal relative to other countries. However, its banks are the region’s largest issuers of labelled bonds, so they tend to issue use-of-proceeds reports rather than comprehensive sustainability reports. Indian banks too lag significantly on the reporting side of things, while their Thai counterparts do very well in this area and are outperformers in sustainable lending overall.

Social:

- As we have seen in other regions, improving social lending comes more easily to banks than improving environmental lending. Affordable housing and lending to small and medium sized companies are key to these efforts and are widely undertaken across the region. Housing is a particular challenge in a heavily populated region which is still undergoing a degree of urbanisation, especially in China, so will remain a key area of focus for the sector for some time.

- Financial inclusion and financial education are crucial areas to watch in this digital age. Most banks now have digital networks which help them to reach poorer, further-flung communities more easily than ever before. However, online banking also raises issues of selling unsuitable products to people who do not understand them. Oversight is very important here. India, for instance, has a sizeable non-bank financial sector (e.g. gold financiers) that dominates lending to the lowest portion of the socio-economic spectrum. However, this sector is not as tightly regulated as the banks. In Indonesia, banks provide call centres for customers and they are required to consent to new products. However, it is not clear how efficient the centres are or what qualifies as customer consent. By contrast, in Hong Kong, banks have to provide detailed information on product features and market trends. Some even hold educational webinars and youth development programmes. They are signatures to the Treat Customers Fairly Charter and have robust documentation detailing their activity/policy in this field.

Governance:

- This is the area in which banks tend to perform most strongly as this is a heavily regulated sector. Financial reporting tends to be detailed (though, as discussed, ESG reporting is more of a mixed bag), almost all banks have a Code of Ethics in place and systemic risks are well controlled. Banks tend to have good working relationships with their regulators – a key focus for us is that this does not become too close, as can happen elsewhere in the world, but in Asia this is not currently a concern.

- There is more room for improvement in the banks’ leadership teams. The proportion of independent directors varies widely across Asia, which causes some concerns in instances where banks have concentrated ownership structures (e.g. state-owned lenders), while the number of women represented on boards is universally disappointing. But perhaps the biggest failing from an ESG point of view is that lack of serious incentives to push management to adopt more sustainable policies. Even though ESG considerations do form a part of KPIs to which managers’ variable compensation is linked, it is only a small part of the package, such that it affects under 20% of board members’ pay even in the more advanced jurisdictions.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox