Governance standards in EM: Diverse country trends don’t go unnoticed by the markets

As part of the ongoing rise in the popularity of ESG, markets have started paying increased attention to various governance indicators not only for corporates, but also for sovereigns. Many asset managers have already developed their own in-house methodologies with the aim of measuring and eventually limiting their funds’ exposures to the emerging markets (EM) countries perceived as laggards in ESG terms. Despite some recent progress in this area, the data for the environmental component of ESG is characterised by significant gaps, definition and measurement issues. Meanwhile, the data on social and governance indicators typically has a much longer history and is more reliable, so naturally carries the largest weight as part of a sovereign’s ESG assessment. In fact, governance indicators have always been important as determinants of countries’ credit quality and thus their credit spreads.

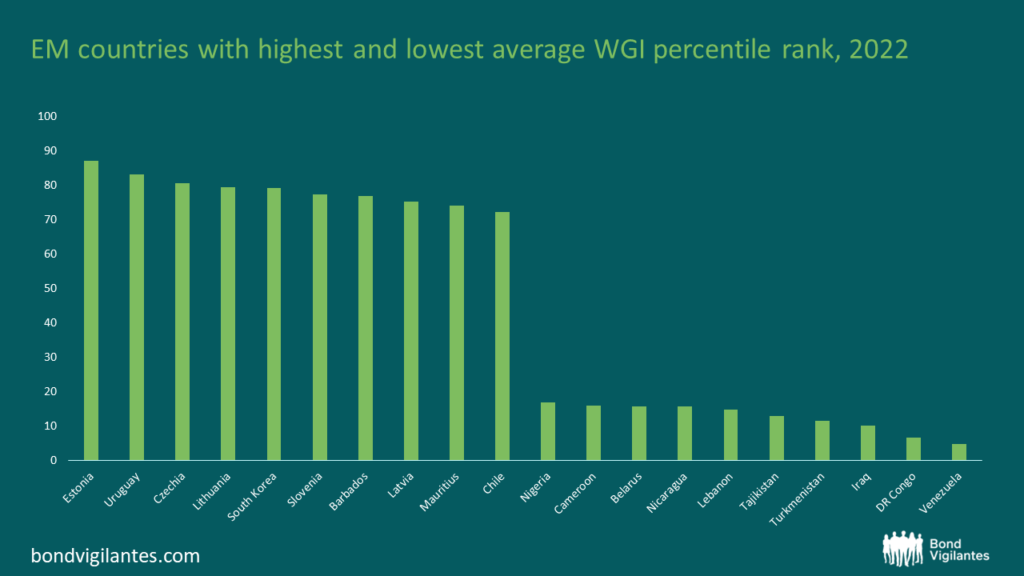

Probably the most trusted and longest-running source of governance data is Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) prepared by the World Bank. They are comprised of six indicators: Government Effectiveness, Political Stability and Absence of Violence, Regulatory Quality, Voice and Accountability, Rule of Law and Control of Corruption. The WGI summarise and aggregate a large amount of data from think tanks, international organizations and the private sector, reflecting a diverse set of views. The data covers more than 200 countries and starts from 1996 (bi-annual updates) and 2002 (annual updates). In contrast to what some people might think, nowadays there are a fair number of EM countries with stronger governance standards than in some of their developed market (DM) counterparts. For example, the average WGI scores (percentile ranks) for Uruguay and Czechia significantly exceed those of Italy and Spain in recent years. Overall, however, there appears to be no broad trend of an improvement for EM relative to DM.

Source: World Bank, M&G (29 September 2023) *Only sovereigns rated by at least one of S&P, Moody’s or Fitch are included

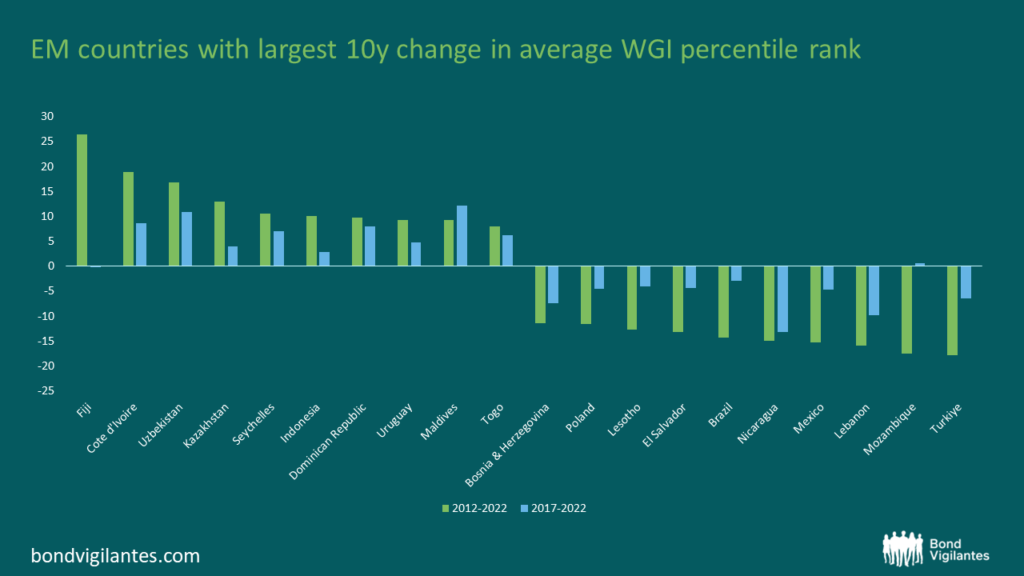

As one would expect, the relative performance of EM countries in terms of governance has been very diverse. In the last decade, by far the best performer has been Fiji, while many other small island states have also made impressive progress. Among those rated by at least one of the three main credit ratings agencies (S&P, Moody’s and Fitch), examples are Seychelles and Maldives. There are many more non-rated island countries (less relevant for the markets) among the best performers as well. This fact seems to suggest that a country’s small size naturally makes it easier to improve its institutional standards. Among larger countries, top performers include Cote d’Ivoire and Uzbekistan, which improved their average WGI rank by as much as 19 points and 17 points, respectively. Trends may not be smooth, as a lot of factors may influence the willingness and ability to reform, such as election calendars. For example, the improvement in Cote d’Ivoire largely paused in 2016-20 before resuming strongly in 2021, once the incumbent president decided to participate in the election at the last minute and was subsequently re-elected for another term. Meanwhile, Uzbekistan’s improvement accelerated in 2017, when the new president came to power and launched a large-scale reform programme across all economic and social sectors. With the president recently re-elected for another term, Uzbekistan’s example so far shows a consistent reform impetus over the years (excluding a brief pause in 2020, with the COVID pandemic being a possible explanation).

It should be noted that Uzbekistan’s improvement started from very weak governance standards. Back in 2012 its average WGI rank was just 11, among the lowest in the world together with countries like Iraq and Venezuela. Fast-forward to 2022 and Uzbekistan’s new comparison peers are the likes of Mexico and Turkey who are not far above in terms of the average rank. It could be argued that it is easier to improve governance from very low levels when a few relatively basic measures (e.g. opening the country to foreign businesses) can have a strong impact. Meanwhile, more advanced reforms often present risks to social stability and can damage interests of established elites, so are harder to implement. Uzbekistan’s neighbour in Central Asia – Kazakhstan – appears to be a good example of this issue. Its reform progress has also been among the fastest across all EM countries during the past decade, but has stalled since 2019, at still moderate levels of governance. A broadly similar story seems to have happened in Fiji (though it managed to achieve relatively high governance levels beforehand). On the other hand, there are also examples of countries, like Estonia and South Korea, which managed to notably improve their governance despite starting from very high levels already.

Source: World Bank, M&G (29 September 2023) *Only sovereigns rated by at least one of S&P, Moody’s or Fitch are included

On the other end of the spectrum, it may be a bit surprising to see a large number of EM countries where governance (on a relative basis) significantly worsened during the past decade. Many of them are in fact among the largest bond issuers in EM, such as Turkey, Mexico, Brazil and South Africa. These countries had moderate governance levels to start with, but there are also countries like Poland and Chile, where significant multi-year deterioration started from very strong levels. Turkey screens as the worst performer globally in the past decade (though the forceful downtrend slowed a bit in the past few years). Market observers would be hardly surprised by this fact, as the controversial constitutional reform, multiple protests, attempted coup d’état, and apparent decrease in the freedom of speech have drawn considerable attention from the global media over the recent years. One would assume that a reverse of such a broad-based multi-year deterioration would only be possible with a change in political elites. This year’s elections in Turkey, leading to the re-election of the incumbent president and the ruling coalition retaining its majority in parliament, may not offer a lot of optimism for the near future. In contrast, in Poland the October’s parliamentary election resulted in a more market-friendly opposition winning, which is widely expected to correct the weakening of checks and balances undertaken by its predecessors. However, as the example of Mexico shows, change in elites is not a guarantee for success – governance continued to deteriorate there even after a new president took power in 2018 (next elections are in 2024).

It is clear that governance standards have a direct impact on the markets, as they are positively correlated with a country’s creditworthiness. The weaker the governance, the higher the risks of a policy mistake which could lead to worsening of a country’s macroeconomic fundamentals. In fact, markets tend to react rather quickly to any significant changes such as election outcomes or new legislation. This is true even for countries with strong governance and macroeconomic fundamentals – the perfect example is Israel, which is ranked far above EM averages on both. Nevertheless, when the government introduced a controversial judicial reform proposal early this year, we saw a notable sell-off in Israel markets (e.g. ILS weakened by 7% vs USD, while 10y sovereign Eurobond spreads widened by about 50bp) within a few weeks after. Similarly, in Poland – another country with strong macroeconomic fundamentals – fixed income markets rallied after a market-friendly opposition coalition secured a win in October elections.

In the medium term, the market impact may be multiplied by the fact that credit rating agencies attach high importance to governance (and WGI specifically) as a determinant for credit ratings. In particular, Fitch assigns a 21% weight to WGI, the highest weighting across all variables, when it determines its model-based rating for a country. Institutional assessment is also a key element in creditworthiness analysis for S&P and Moody’s. Consequently, it’s not a coincidence that some of the best-performing countries (e.g. Uruguay, Cote d’Ivoire, Indonesia) in terms of governance achieved upgrades from the rating agencies in the past decade. Conversely, the worst-performers like Turkey, Mexico and Brazil saw downgrades by a few notches. The case of Turkey is especially vivid, as it was downgraded by a higher degree than would be implied by the worsening of its macroeconomic fundamentals. The reason was that weakened policies (such as lower central bank independence) significantly increased the tail risks of a disorderly economic crisis.

To summarise, despite broad economic and social progress across the world in recent years, the expected improvements in governance in EM countries are far from a given. In contrast, some countries have seen significant deterioration recently, at least in relative terms. Fortunately, at some point sooner or later, it is often the markets that have the power to arrest the negative developments and impose a certain degree of discipline. A helping hand may come from the high dependence of a country on external financing, as weaker governance eventually increases its cost of borrowing to unaffordable levels. All things being equal, this can happen much more quickly in countries with stronger governance (like in Israel where the government softened its judicial reform proposal after negative market reaction and public protests). It took a long time in Turkey, but the significant deterioration in macroeconomic conditions seems to have finally shifted policies for the better in recent months, despite no change in the ruling elites. In light of this, there is hope for other EM countries with similarly deteriorating governance.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.