If we are all dead in the long term, does it even matter?

The IMF recently released their latest World Economic Outlook, subtitled “Steady but Slow”, which nearly characterises the prevailing macroeconomic wisdom that global growth is tepid but without drama, and will remain pretty much like this over their five year forecast horizon. The IMF note that growth would have been weaker still if it were not for US fiscal largess, where the deficit is still running at 6% of GDP and expected to remain there in coming years. If Trump returns, it might even accelerate. We have written about debt concerns before here, but in truth, the rise in global bond yields had nothing to do with fiscal policy and everything to do with the de-anchoring of inflation. US 10 year Treasury bonds have risen from 0.5% to a current 4.6% in the past two years. I would suggest this kind of reaction and the volatility around the move is a function of acute regime uncertainty.

For patient investors, regime is worth thinking about because the general belief is asset valuations tend to be drawn (eventually) to levels consistent with what we shall call the fundamentals that are the output of the regime itself. Caveats include Keynes’s quip that in the long term we are all dead, or equally his observation that the application of rationality in an irritational market can result in insolvency before it results in riches (remember hedge fund Melvin Capital, famously short of GameStop, obliterated by investors unconcerned with minor details like the company’s inability to generate any positive earnings or the current valuation being put on Truth Social for that matter).

Still, few fund managers would disagree that some degree of attention should be paid to growth, inflation, interest rates, central bank reaction functions, fiscal policy, productivity, capital accounts and so on, and that changes in the long term outlook for these variables are likely to have implications for markets. Precisely which variables to follow, what weight to assign to them or what effect they will have on markets, are matters for debate that would have even distracted Socrates from enquiring on other weighty matters like “what do you know?”.

Mind you, despite being 2 ½ thousand years old, that’s a pretty good question to start with, and clever answers that involve various permutations of the words ‘known’ and ‘unknown’, still result in the end with a conclusion that is close to ‘not a lot’. Some humility might be useful at this point, though replies of ‘I don’t know’ to all questions except your name, age and occupation, play poorly on Bloomberg TV. I suggest distracting the interviewer with how great the 1984 R.E.M. concert at the Lyceum Theatre was.

In the past 3 years it has been inflation that has dominated the macroeconomic narrative. Unspent stimulus cheques, supply chain bottlenecks and war have been the identified culprits, with emphasis depending on who you’re talking to. The uncertainty of the inflation regime we are in has been touched on before here and this continues to cause bond markets to oscillate wildly on little more than a couple of high frequency data points. If only we could forecast the pesky thing we’d be in better shape. That issue has received further airtime in the recent Ben Bernanke report on “Forecasting for monetary policy making and communication at the Bank of England”.

If one needed to put a final nail in the coffin of any investment process that sets forecasting as an objective and claimed skill, this report does the trick, noting pretty much no central banks around the world, despite all their resources specifically dedicated to modelling price behaviour, anticipated the inflation shock. What chance has an asset manager with a couple of smart economists? No real surprise here for regular readers of this blog, who will be familiar with our caution regarding such an approach. Nevertheless, it does beg the question, what then can we know if we can’t predict inflation or other economic variables and how does one go about buying 10, 20 or even 50 year maturity bonds with no idea what the future holds?

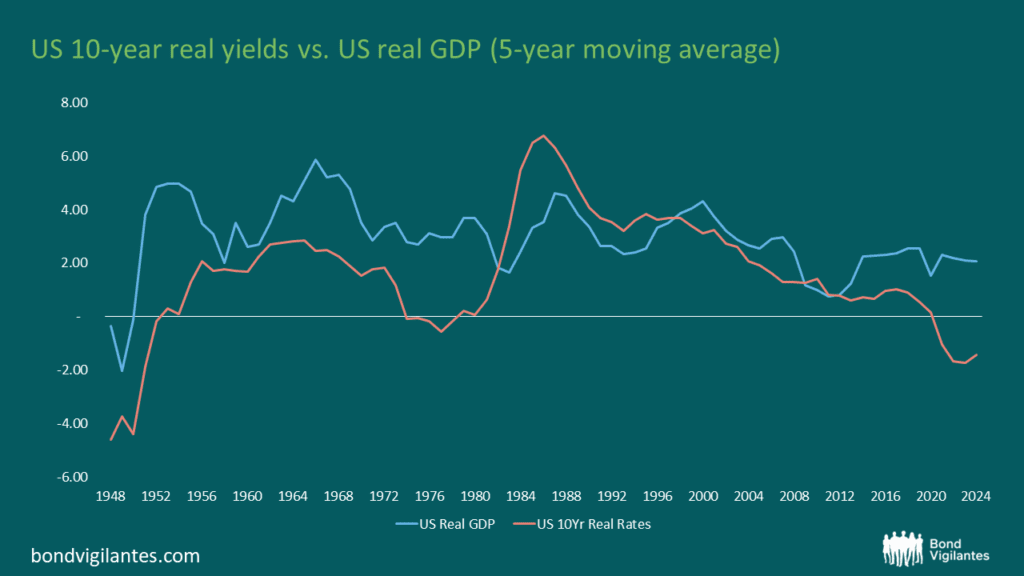

The equilibrium approach has an answer to this. Whilst I can say close to nothing about next year, next month or even the next day, perhaps I can say more about 3, 5 or 7 years from now? If we know something about populations and productivity, we can have a stab at longer term growth potential, and if we know real growth, perhaps a view on real interest rates isn’t far away? If we can trust central banks when they tell us they will do what it takes to deliver 2% inflation, then, hey presto, we have a nominal interest rate that might mean something and we can go and buy some long dated bonds when yields are well in excess of this figure, to allow for a margin of safety. Of course, there were a lot of ifs in all that, and what’s more, empirically it’s tricky because the relationship between real rates and real growth has been, well, pretty variable through time, sufficiently so for some of my erstwhile colleagues (with multidecade alpha track records to their names) to call it a fallacy and as the chart below illustrates, they have a point.

Source: Datastream, Robert Shiller

Perhaps what squares this circle is the question of regime. The fallacy is a result of the fact that the world has changed a great deal in many fundamental ways over the past 50 years. The death of fixed exchange rates in the early ‘70s, the rise of inflation targeting in the early ‘80s, or pace of change in global technology. As an aside, the last of these is particularly intriguing given the impending AI Revolution (no AI was used to write this) because in the world of real rates, potential growth is key and technology should drive productivity that drives growth. Except, despite all the new technology, potential growth rates have collapsed; estimates for the US by the Bureau of Economic Analysis have fallen from 3.1% in 1970 to 1.8% now, a 40% decline. This might not help in understanding the role of technology, but it does at least help us understand why real interest rates have fallen. If productivity remains uninspiring, that’s a strong headwind for a long term rising trend in real rates.

Even if me spending 4 hours a day on my phone (thank you fancy smart phone for keeping me informed) isn’t doing anything to drive growth, one possible bright spot is immigration. Young, skilled and enthusiastic workers are unequivocally good for an economy and can certainly lift labour productivity for all the obvious reasons. Unfortunately, the political and social appetite for this appears limited as a long term solution even if some near term numbers are encouraging. Plus the demographic headwind from otherwise aging populations is going to accelerate. Returning to the IMF Outlook, they don’t seem inspired. Global growth is forecast to be 3.1% in 5 years’ time, “the lowest in decades”.

Somehow, I have an affinity to their view. It is of course possible AI will be the productivity miracle that we thought the internet would be (but wasn’t), but until I see it as useful for much except asking it to write me a Sonnet on the drivers of real interest rates (wasn’t bad), I’ll struggle to believe it. Add demographics, deglobalisation and debt and it feels hard to get excited about growth. And there we have the bare bones of a regime where growth is uninspiring. Even allowing for the ‘David Knee fallacy’ of real interest rates, I’d suggest we might look back and think US 10 year bonds close to 5% was a decent yield for those prepared to lock away their capital. Risks and uncertainties abound, not least on the question of equilibrium inflation where theory has thrown up its hands in despair. For the tactically minded, western government bonds also offer a safer place to hold capital against the wafer thin corporate bond spreads now on offer and give a war chest of reserves to deploy when better value eventually presents itself. For the patient, it always does.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.