The Inefficiency of Monetary Policy Amidst High Wealth Inequality

In recent years, monetary policy has been a cornerstone of economic management, aimed at controlling inflation, stabilising currency, and fostering economic growth. However, its effectiveness is increasingly questioned in the context of rising wealth inequality. When wealth inequality reaches high levels, monetary policy impacts become unevenly distributed, which can in turn further exacerbate the disparity. This blog explores how monetary policy can be inefficient in such an environment, highlighting the greater challenges faced by lower-income individuals due to high debt costs and an increased cost-of-living, as well as the benefits reaped by those with savings due to higher interest rates and the appreciation of assets.

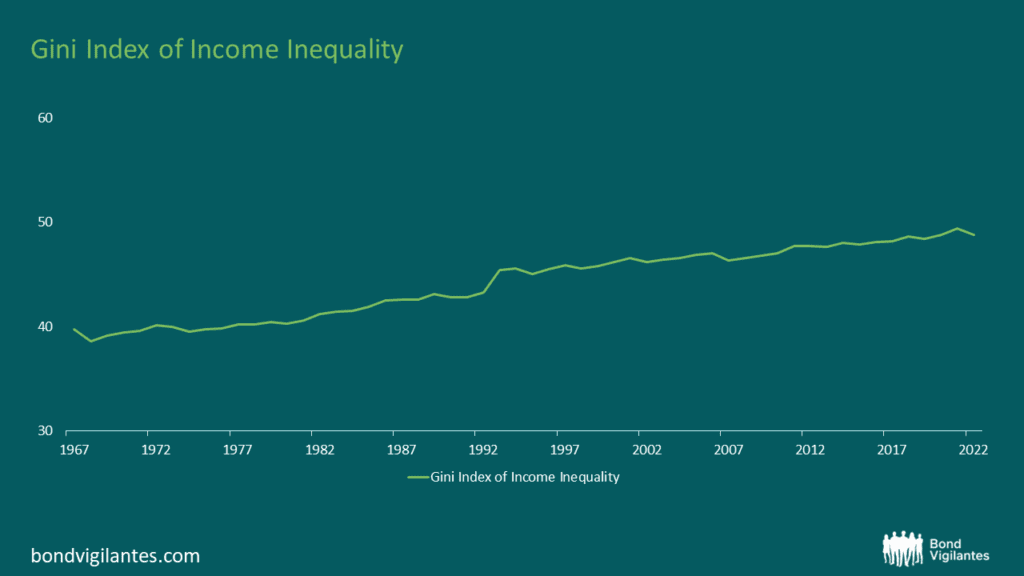

Wealth inequality is the uneven distribution of assets and wealth across a population. When this gap widens, a significant portion of the population holds very little wealth, while a small fraction accumulates substantial assets. This disparity can influence how different segments of society experience the effects of monetary policy. The Gini coefficient measures the extent to which the distribution of income among individuals or households within an economy deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. A Gini index of zero represents perfect equality and 100, perfect inequality. As we can see from the following chart, over time the coefficient has been steadily trending towards further inequality.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg, July 2024

On the surface, aggregate economic data often appears robust. Metrics such as Gross Domestic Product (‘GDP’), employment rates and inflation tend to suggest a healthy economy. Observing these indicators, central banks may adjust monetary policy, such as altering interest rates, to steer the economy toward desired outcomes. However, these aggregate measures can mask underlying disparities:

- GDP growth: while GDP may rise, the benefits of this growth are often concentrated among the wealthiest. For instance, increased corporate profits boost GDP but do not necessarily translate into higher wages or job security for the working class.

- Employment rates: low unemployment rates can be misleading, if, for example, many jobs are low-paying or part-time. Full employment in such a scenario does not equate to economic security across the whole population.

- Inflation: a moderate inflation rate might seem manageable overall, but it disproportionately affects low-income households, who spend a larger proportion of their income on essentials.

Disproportionate impact on those with low incomes

For those with limited wealth, high debt costs and the burden of living expenses create significant financial strain. Here’s how monetary policy, particularly in the context of high wealth inequality, can exacerbate these issues:

- High cost of debt: low-income individuals often rely on credit to cover basic needs, leading to higher debt levels. When central banks raise interest rates to curb inflation, the cost of servicing this debt increases. This can lead to a vicious cycle of debt accumulation and financial hardship for low-income individuals who struggle to make ends meet. We have looked at some of these strains on the consumer here.

- Inflation and living costs: inflation affects everyone but impacts people with low incomes the most. As prices for food, housing, and utilities rise, those with limited financial resources face increased difficulty in maintaining their standard of living.

Benefits for the wealthy

Conversely, those with substantial savings and investments often benefit from high interest rates and other monetary policy measures:

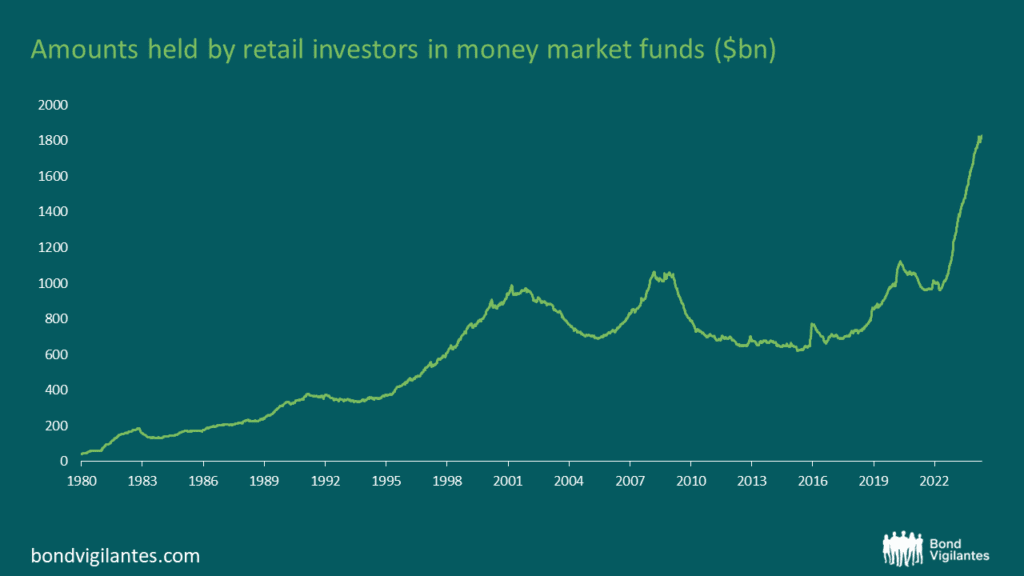

- Higher interest rates on savings: individuals with significant savings enjoy better returns when interest rates rise. This can lead to an increase in wealth without any corresponding increase in productivity or labour. The size of retail money market funds (below) is at an all-time high, with investors enjoying circa 5% returns.

Source: Bloomberg, July 2024

2. Asset appreciation: policies that stabilise or boost markets can lead to appreciation in asset values, including stocks and real estate. Since those with greater wealth hold more of these assets, they gain more from such increases.

Demographics is also at play

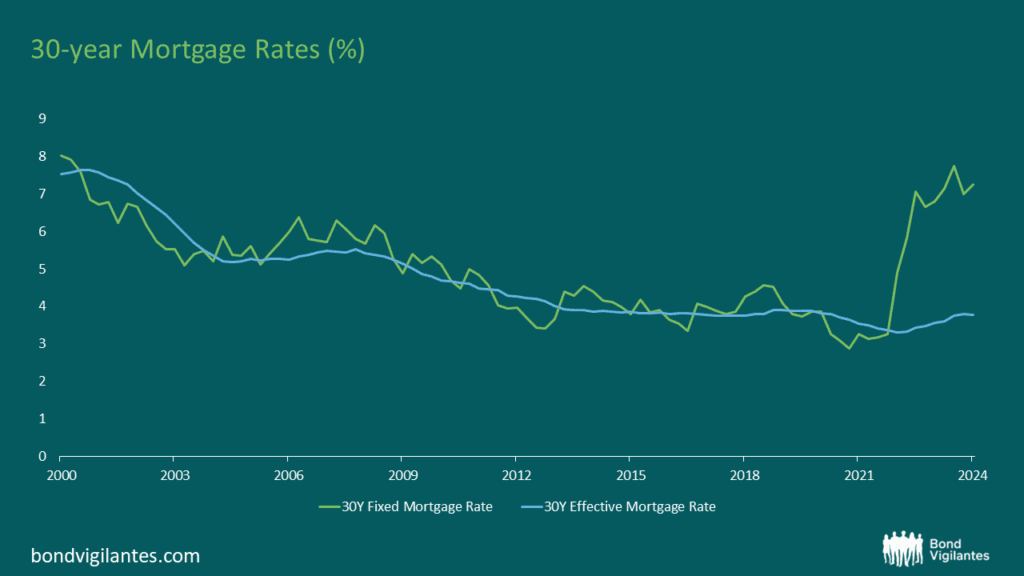

Another interesting consideration is demographics, and specifically when it comes to age, where we see a similar disparity in the effects of monetary policy. People from middle-to-older generations may have been able to pay down debts and accumulate savings, whereas those from younger generations looking to get onto the property ladder are having to do so with a combination of relatively low incomes, higher levels of debt (due to elevated asset prices) and higher costs of debt (due to higher interest rates). We illustrate this by looking at 30-year mortgage rates in the below chart. Almost all people pre-2022 will have locked in to long-term mortgages at lower interest rates, whereas currently, people (who are typically younger) are facing higher levels of interest.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg, July 2024

The inefficiency of monetary policy

In conclusion, the core inefficiency of monetary policy in the context of high wealth inequality is its inability to address the uneven distribution of economic benefits. While central banks can influence overall economic conditions, they cannot directly mitigate the disparities in how these conditions affect different socioeconomic groups. Some key points of this inefficiency include:

- One-Size-Fits-All approach: monetary policy is often a blunt instrument applied uniformly across the economy. This approach does not account for the varied financial situations of individuals within the economy.

- Exacerbation of inequality: by raising the cost of debt and increasing returns on savings, monetary policy can inadvertently widen the wealth gap. This can undermine social cohesion and economic stability over the long term.

- Limited reach: while intended to stabilise the economy, monetary policy often fails to effectively reach the lower strata of society. Fiscal policies to redistribute wealth or directly support low-income households may complement monetary efforts.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.