Economic juggling: the complexities of monetary policy amid soaring debt

In recent years, the transmission mechanism of monetary policy—the intricate process through which central bank actions impact the economy—has undergone significant changes, notably as global debt levels have surged. With governments around the world carrying heavier debt burdens, the impact of rising interest rates on the economy has shifted in ways that policymakers must grapple with. This complex situation underscores the need for a deeper understanding of the economic dynamics. One of the most pressing issues is the effect of increasing interest payments on government debt, reshaping how central banks think about and implement monetary policy.

The traditional transmission mechanism

Historically, central banks have used interest rates as their primary tool to influence economic activity. When inflation is high, or the economy is overheating, central banks raise interest rates to cool demand by making borrowing more expensive. Conversely, when the economy is sluggish, they lower rates to stimulate spending and investment by making credit cheaper.

This process works through several channels:

- Interest rates: higher rates increase the borrowing costs for businesses and consumers, reducing spending and investment, and vice versa.

- Wealth effect: changes in interest rates affect asset prices, which influence household wealth and, in turn, consumer spending.

- Exchange rates: higher interest rates can attract foreign capital, strengthen the domestic currency, and impact trade balances.

However, with unprecedented levels of government debt, the traditional transmission of monetary policy is becoming increasingly complicated.

The role of high debt in changing the transmission mechanism

Now government debt is at historically high levels, the impact of interest rate changes reverberates more strongly through fiscal channels. Rising interest rates affect private borrowers and significantly increase the cost of servicing government debt. This creates a feedback loop between monetary and fiscal policy, which may ultimately constrain the central bank’s ability to use its tools as freely as it did in the past.

Rising interest payments and the fiscal-monetary policy nexus

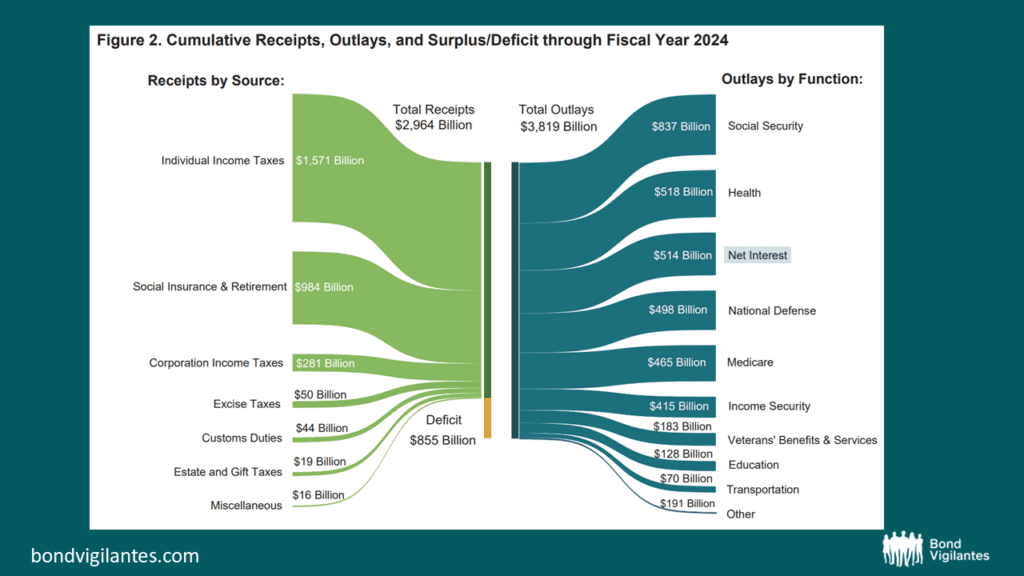

As interest rates rise, governments must allocate more of their budgets to debt servicing costs. This presents a significant dilemma: higher interest payments can crowd out other forms of government spending, such as infrastructure investments, social programs, or healthcare. In countries with very high debt-to-GDP ratios, such as the United States, Japan, and several European nations, the cost of debt servicing has become a substantial part of the national budget.

The figure below illustrates the substantial size of the US net interest expense. It’s on track to be the second largest outlay, second only to Social Security. Perhaps this is why Japan, with its 250% debt to GDP, has been so slow to raise interest rates.

Source: US Department of the Treasury, Monthly Statement, April 2024.

This increase in government spending on interest payments due to rising rates means two things:

- Constrained fiscal policy: governments may have less room to manoeuvre when it comes to fiscal stimulus, as a larger proportion of their revenue goes towards interest payments. This could limit the effectiveness of countercyclical fiscal measures in future recessions.

- Political pressure on central banks: central banks may face political pressure to keep interest rates low to help reduce the government’s borrowing costs. This creates a risk of ‘fiscal dominance’, where the need to manage government debt trumps the central bank’s focus on controlling inflation.

The impact on economic growth

The rising cost of government debt can also significantly dampen economic growth. As governments are forced to spend more on debt servicing, they may cut back on productive investments that drive long-term economic growth. The gravity of the situation is a cause for concern. Additionally, higher interest rates can squeeze private-sector borrowing, especially for small businesses and consumers, leading to lower levels of economic activity overall.

How high debt affects central bank decisions

A central bank’s traditional objective is to manage inflation and stabilise the economy. However, with high debt levels, central bankers must now also consider the fiscal implications of their actions. Raising interest rates aggressively to combat inflation could potentially destabilise public finances, especially if governments are already struggling with large deficits and high debt loads.

For example, a country with high debt that faces rising interest rates may see its credit rating downgraded, leading to higher borrowing costs and a vicious cycle of debt accumulation. Central banks may be forced to adopt a more cautious approach to tightening monetary policy, even when inflation rises, to avoid exacerbating fiscal pressures. This caution could lead to a situation of ‘fiscal dominance’, where the central bank’s ability to control inflation is compromised by political pressure to keep interest rates low for the government’s benefit, highlighting the potential risks to inflation control when central bank independence is threatened.

Changing policy transmission

Another significant shift in the transmission mechanism is that high debt levels have led to greater uncertainty about how quickly or effectively monetary policy actions translate into economic outcomes and through which channel—monetary or fiscal.

Consider a scenario where a central bank hesitates to raise rates due to concerns over government debt. In this case, inflation could persist at high levels, diminishing purchasing power and undermining the efficacy of future policy interventions. This erosion of the central bank’s control over inflation due to ‘fiscal dominance’ could result in less effective future policy interventions, highlighting the enduring impact of high debt levels on the economy.

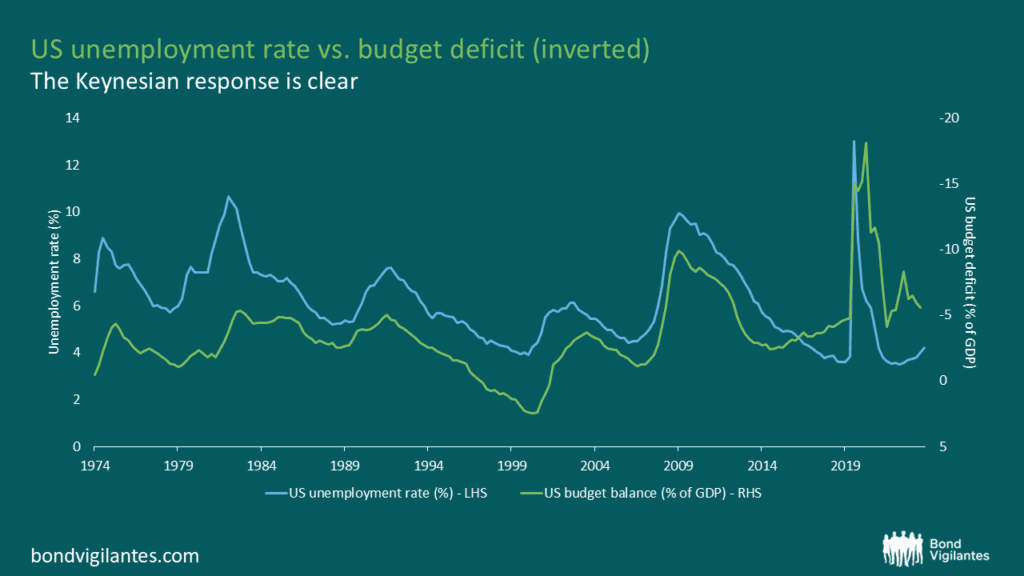

The US economy, along with others, is approaching a critical juncture, with the upcoming election potentially serving as a catalyst. Despite being in the fourth year of economic expansion and with unemployment at or near all-time lows, current deficit levels mirror those seen during recessionary periods.

The chart below shows the unemployment rate vs. the deficit (inverted):

Source: Bloomberg, M&G, August 2024

When the next economic downturn arrives, the government may find itself in a precarious situation. Will it be able to respond with a Keynesian splurge given the current levels of debt and deficits? If the new administration fails to curb spending, the market may force austerity measures on the government. Fearing this outcome, the government will likely have to tighten fiscal spending, potentially leading to an economic slowdown.

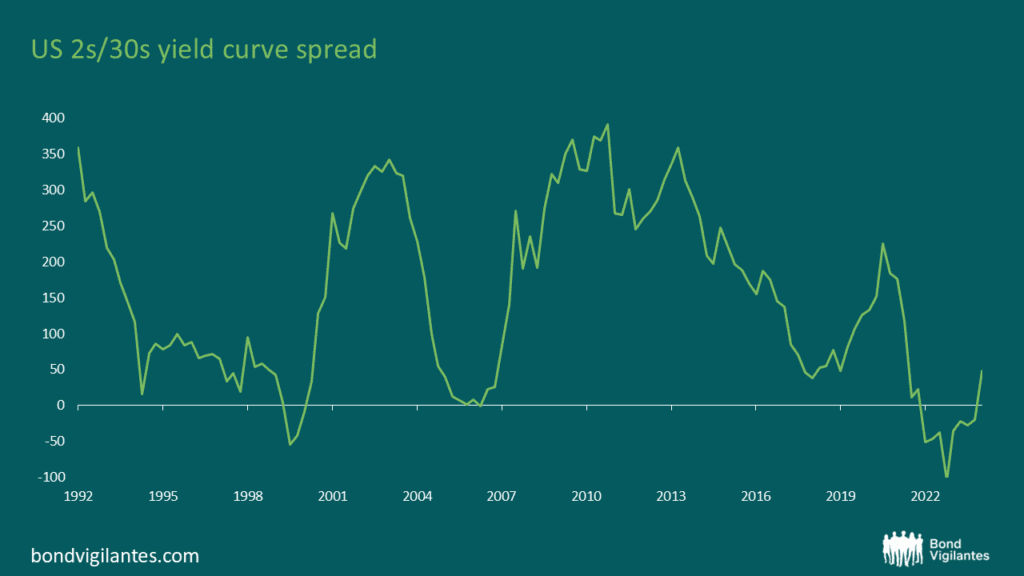

This dynamic has made life increasingly difficult for investors, and they should remain cautious. With interest rates starting to move lower on the back of rate cuts and valuations looking stretched with still relatively flat curves, fixed income is at risk of yields moving materially steeper as investors lose confidence or central banks respond to an economic slowdown.

From a long term perspective, the curve remains exceptionally flat:

Source: M&G, Bloomberg as at September 2024

Worryingly, politicians seem more concerned about people eating dogs and cats over the pending fiscal crisis. Perhaps investors will continue turning to alternative assets such as gold, which is known to protect against inflation, currency devaluation and geopolitical risk, which seems to be rising by the day. Alternatively, we may see a greater focus on economies with strong fiscal positions and low outstanding debt.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.