Hybrid capital for Development Banks – an emerging asset class?

In January 2024, the African Development Bank (AfDB) issued the first hybrid capital instrument ever issued by a Multilateral Development Bank (MDB). Despite initial hopes that this would be the first of several such instruments, allowing MDBs to leverage private capital to support development projects globally, this remains the only such bond in existence. Why has this market failed to grow? Is this instrument really suitable for MDBs? And does it have a natural investor base?

It’s worth pointing out that there is huge political weight behind the use of hybrid capital to bolster MDBs’ equity bases. In 2022, the G20 commissioned a report into the subject, which was highly supportive. One can see why. Hybrid capital is accounted for as 100% equity under accounting standards and by the credit rating agencies, so for every dollar raised the bank can lend at least two while protecting its credit rating. And, of course, raising private capital means that the shareholding governments are spared the expense of having to increase MDBs’ capital themselves, though there is some cost to the bank of servicing this debt. One can therefore see the attraction from national capitals’ point of view, so it came as no surprise that another G20 report followed in 2023 assessing MDBs’ progress in implementing the recommended hybrid capital programmes. Momentum kept building until AfDB finally launched its inaugural hybrid instrument in January 2024. Since then, however, there has been silence on the subject. Given the benefits that hybrid instruments confer on banks and (indirectly) governments, we suspect that the difficulty is a certain level of scepticism in the investor community.

The main issue is that hybrid capital does not marry up well with MDBs’ traditional investor base. Bonds issued by MDBs are very safe, low-yielding investments. AfDB senior bonds, for instance, are rated AAA and the 3.5% 2029 senior bond trades at around z+40bps (equivalent to just 9bps over US Treasuries). The tight spreads reflect its high rating, strong ownership and the benefit its preferred creditor status confers on its asset quality. Its high rating rests on three factors: its strong liquidity, low leverage (at end-2023, $14.5bn of equity supported just $29.5bn of loans) and the support of over $180bn of callable capital from its shareholders should it not be able to service its obligations. This means that there is a guaranteed pool of government cash for bondholders to fall back on that is almost four times the size of the bank’s assets ($53bn) and six times all its outstanding borrowings ($33bn).

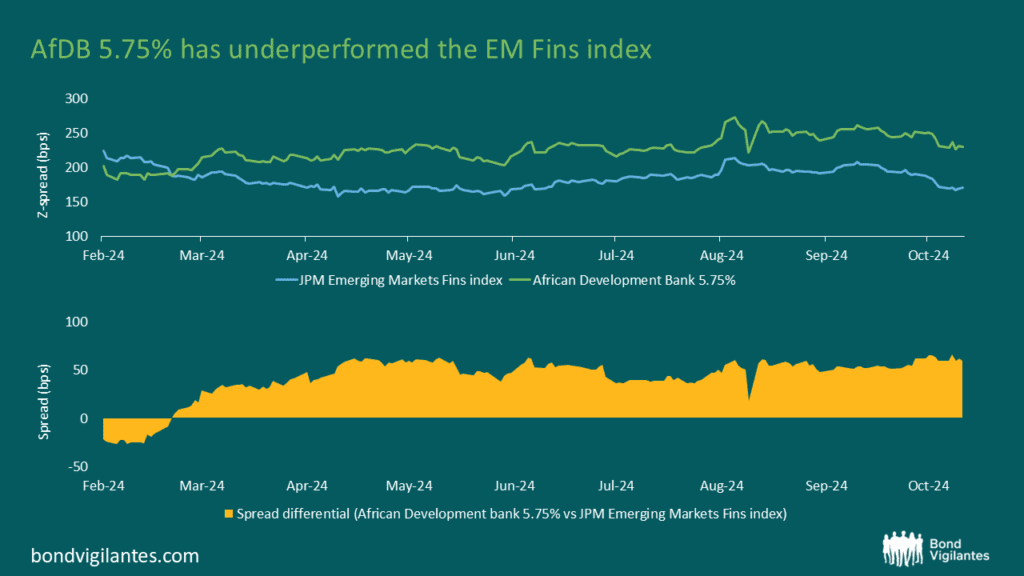

A glance through the terms of the hybrid instrument, however, reveals that this is much riskier than the senior bonds. Coupon payments are discretionary and must be cancelled if leverage (Total Assets/Total Equity) rises above 7.5x (for context, over the past five years, this ratio has ranged between 3.5x and 4.8x); the bank cannot call the notes if this ratio is breached until the issue has been fixed; and the notes must be written down to zero if a call is made on callable capital (note that this excludes the regular capital infusions that occur every 8-12 years). So not only is there a risk of missed payments (inconceivable for senior instruments), but the vast store of callable capital that underpins the bank’s AAA rating is not available to holders of the hybrid instruments. And as the AA- hybrid rating is notched down mechanically from the senior rating and pricing dynamics are heavily influenced by the rating, this raises questions about whether or not pricing reflects the risks involved with this instrument. There is also the technical question of index inclusion to consider – because of its subordination, MDBs’ hybrid capital is not eligible for inclusion in the usual benchmarks, lowering the missed opportunity cost to wary investors. All this is reflected in the bond’s relatively weak performance compared to JPMorgan’s CEMBI Financials index (see chart below).

Source: M&G, Bloomberg as at October 2024

All this is reflected in the investor distribution for AfDB’s January deal. Hedge funds and specialised funds accounted for 55% of investors, while large traditional buy-side players like pension/insurance funds (6%) and banks/private banks (4%) were relatively absent. By region, 55% went into the UK and 27% to EMEA, whereas a mere 8% was allocated to the Americas, which is highly unusual for high-quality USD-denominated paper. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the bank struggled to find anything more than a relatively specialised investor base. One can see why: a subordinated bond carrying risks to coupon and principal payments would not be suitable for traditional risk-averse MDB investors, while those looking for more risk in the subordinated financials space would find greater returns available elsewhere. For the multilateral development bank hybrid debt market to develop as the G20 intends, pricing needs to reflect properly the risk presented by the instrument.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.