Kaos Theory

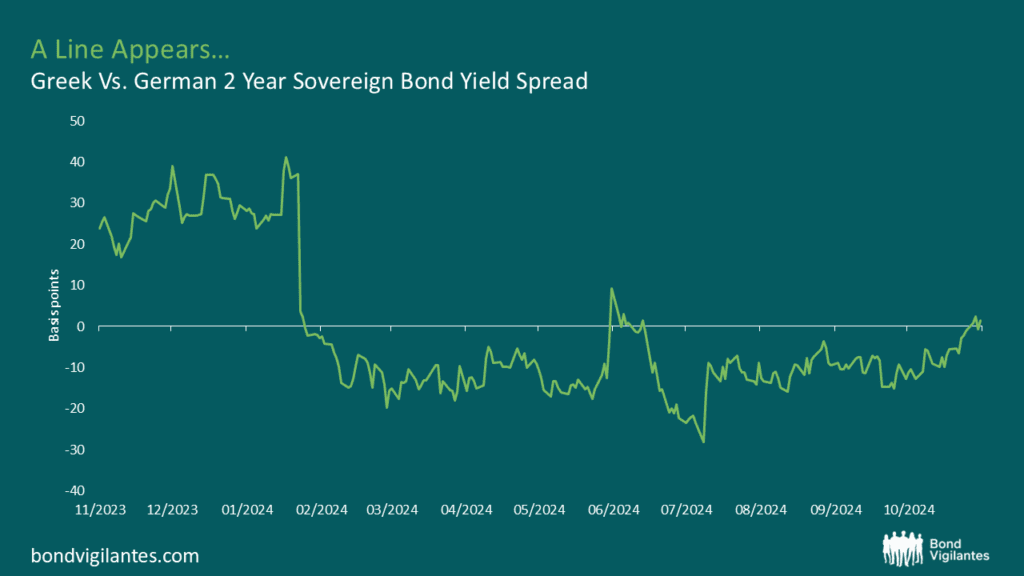

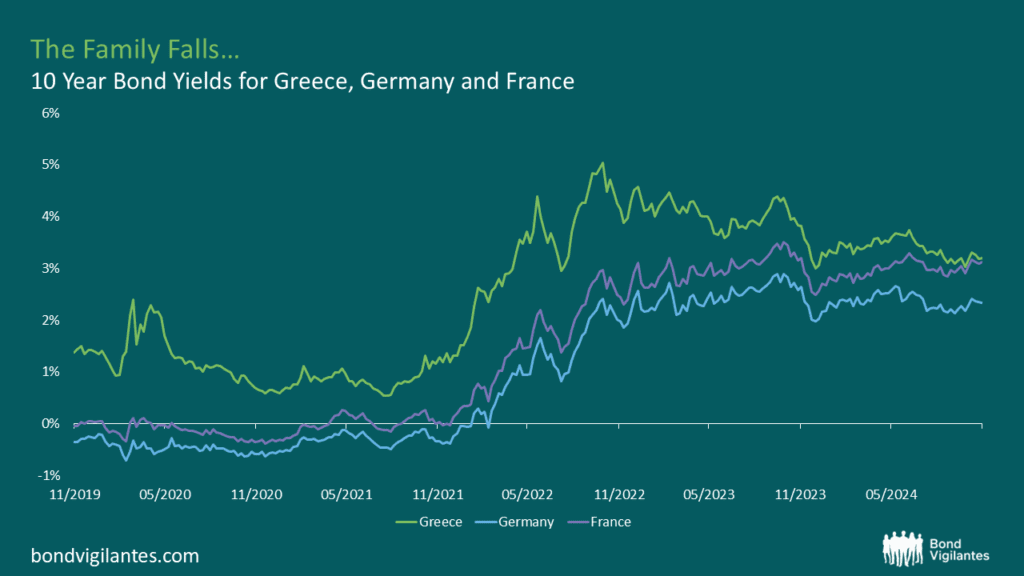

Fans of the neo-classical Netflix drama ‘Kaos’ will be pleased to know that Eurydice was not alone in returning from the abyss. Followers of European bond yield differentials have witnessed a comeback story of similar scale: Greece can now borrow in world markets at similar rates to Germany’s at the 2-year mark, and below French bond yields across several maturities. Is this a bolt from Olympus, or have the Fates ordained a devious plan?

As with all ancient Greek legends, Zeus’ Netflix downfall is announced by a prophecy:

“A line appears, the order wanes, the family falls, and Kaos reigns”.

The cryptic prediction provides a perfectly apt description of the European debt markets with particular reference to Greece. Let’s decode the critical warnings together.

The Netflix Zeus is reduced to a paranoid wreck whilst trying to fathom the significance of a number of sinister ‘lines’ in the plot – an interruption to the flow of the Meander fountain, a cut to the finger, a wrinkle to his forehead. Luckily, I’ve prepared only one line for us to dissect.

Source: Bloomberg, as at November 2024

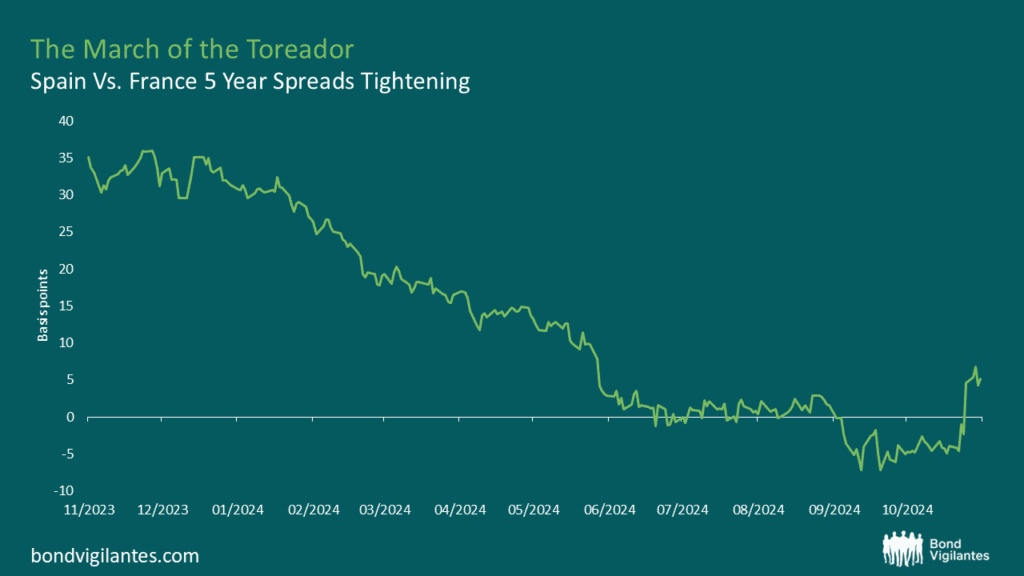

In many ways, the deterioration between German and Greek bond yields is not surprising. In March 2024, the German governing coalition collapsed, inflation remained a going concern due to higher than expected energy prices[1], and exports lagged expectations[2]. This is a painful mix of bad news for any economy to stomach, not including the recent sell-off in 10-year bunds[3] reported on November 23rd. It could therefore be argued that it was a German depreciation as opposed to a Greek appreciation in performance that led to the tightening of the spread. However, Greece is not alone in its advance. Spain’s borrowing terms also improved relative to core Europe[4], as have Portugal’s.

Source: Bloomberg, as at November 2024

Recent history tells us that when there are political or economic issues in core Europe, the periphery tends to be marked down in tandem. This time, Spain, Greece and Portugal have held firm whilst core European bond markets have absorbed political and economic flack, much to the detriment of their respective yields. A delightful exposition on this can be found (shameless plug) in Robert Burrows most recent Bond Vigilante piece[5], paying particular attention to the current predicament facing France.

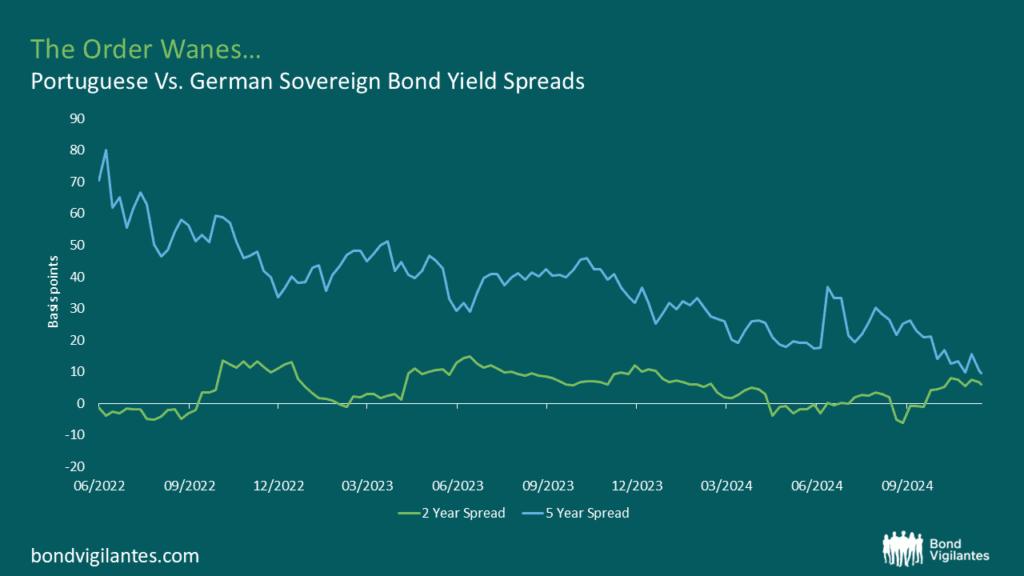

We see further evidence with regard to the tightening of spreads across both 2- and 5-year Portuguese sovereign bonds relative to their German counterparts, too. What’s interesting with this sentiment is that it mirrors the sentiment of the European Commission from one of their papers back in 2009[6]…

Source: Bloomberg, as at November 2024

But wait, there’s more: if we were to cast our memories back even further, say 25 years, this all actually starts to look rather familiar.

‘Some argue that Germany’s ugly recent statistics can be blamed as much on a series of one-off shocks as on the economy’s structural faults. Once these have passed, the optimists go on to argue, growth should start to take off again.’

‘Germany can hardly claim that its malaise is a rich-world commonplace. The American economy is still booming, for now.’

Let’s be generous. Those two quotes could be said of Germany’s economy right now. They were, in fact, written back in 1999 in the famous Economist article ‘The Sick Man of the Euro’[7]. This was a time when bond markets were theorising that the Eurozone should all be able to borrow at similar rates owing to the fact that they used the same currency. We see evidence of this borne out in bond yield compression in countries converging to the euro in this paper from 2005[8], as well as prevailing contemporary market sentiment.

Germany was the outlier and its, ‘weakness has, indeed, come at an especially awkward time for the euro’ (again, from the Economist in 1999). Convergence was the topic du jour and it seemingly wasn’t taking place in the noughties. I should know; I was 2 years old after all. Now, though, we have far more evidence of convergence within the Eurozone.

Source: Bloomberg, as at November 2024

I spoke to an Economist recently, who said, ‘Private markets forgive and forget much quicker than we might realise,’ and this is certainly ringing true. We may not be far off from another Walter Wriston moment with someone boldly declaring that ‘Sovereign nations don’t go broke,’[9], only to be treated moments later to another version of the ‘painful photo of Michel Camdessus’[10] with Indonesian President Suharto. What Wriston says may be true when countries control their own currencies, but not all busts are alike nowadays.

Let’s just say that the sovereign bond default now seems to have been replaced by something more akin to a national corporate bankruptcy. As an aside, this might be why the American economy can rebound so fast from crises, relative to the rest of the world, courtesy of well-known Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings.

Just as the old bond vigilantes forgot about the 1997 Russian crisis which ended up with Russia borrowing on Germanic rates in 1999 (see the conclusion of the book ‘Russia Rebounds’ by the IMF[11]), now we have private capital returning to Greece, but resisting investment in core European heavy industry, driving yield convergence again.

In the words of one of my favourite songs, ‘What goes around, just comes around’ (Timo Maas, To Get Down[12])…

But does chaos actually reign?

Perhaps not. Herodotus opined that ‘no one can escape the wrath of the Fates. Not even the Gods’. In the Netflix version, Zeus loses his despotic powers through failure to accept greater freedom for his subjects. Human intransigence is what he sees as chaos. One such intransigent was Sisyphus, condemned to an eternity of pushing a rock up a hill for cheating death. Greece has pushed its economy up the hill towards the sunny uplands which are now clearly visible. Germany, whose fiscal virtue has kept its rock balanced at the top of the peak, has now lost its grip.

This may not be chaos, but cyclicality. It may look bleak now, but bond vigilantes have extremely short memories, even if the Gods do not…

Now, if anyone knows where I can get Jeff Goldblum’s tracksuit from Episode 1, I’d be eternally grateful, as it’s a thing of sartorial beauty.

[1] Top economists downgrade Germany’s growth forecasts – Financial Times

[2] Germany’s economy goes from bad to worse – The Economist

[3] German bond investors bet on an end to Berlin’s ‘debt brake’ – Financial Times

[4] Spain’s GDP growth accelerates, leaving it on track to be fastest-growing big advanced economy – Financial Times

[5] Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the most worrisome of them all? – Bond Vigilantes

[6] Determinants of intra-euro area government bond spreads during the financial crisis – European Commission

[7] The sick man of the euro – The Economist

[8] Bond Yield Compression in the Countries Converging to the Euro – Sacred Heart University

[9] Too Big to Fail?: Walter Wriston and Citibank – Harvard Business Review

[10] 20th Anniversary, Asian Financial Crisis: Clinton, The IMF And Wall Street Journal Toppled Suharto – Forbes

[11] Debt Crisis in Russia: The Road from Default to Sustainability – IMF

[12] The Italian Job – YouTube

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.