What’s so special about 4.7-year bonds?

“How are you going to screw me?”…That’s a question a US investor asked an investment banker who was offering a trade that seemed too good to be true. Michael Lewis told the story in a 2008 article, when, understandably, trust in Wall Street banks wasn’t at its peak. I think it fair to say that, thanks to changes in regulation and culture, many of the games played on investors pre-GFC (Global Financial Crisis) are far less common today (does anyone remember CDO-squareds?). But the banks still have smart people who are capable of finding little gimmicks that make trades look better than they really are at first glance.

Which brings me to a flurry of GBP bonds with odd tenors issued in the UK corporate bond market in the last few weeks, including several bonds with a time-to-maturity or call date of 4.7 years. While issuers can choose their bond maturities for any number of reasons, it seems the choice of this particular maturity or call date – between October and December 2029 – is driven by a pricing convention that makes the bonds look optically cheaper than they really are. This little trick exists in the sterling market because of two factors: the way UK retail investors are taxed on UK gilts, and the sharp rise in rates seen since late 2021.

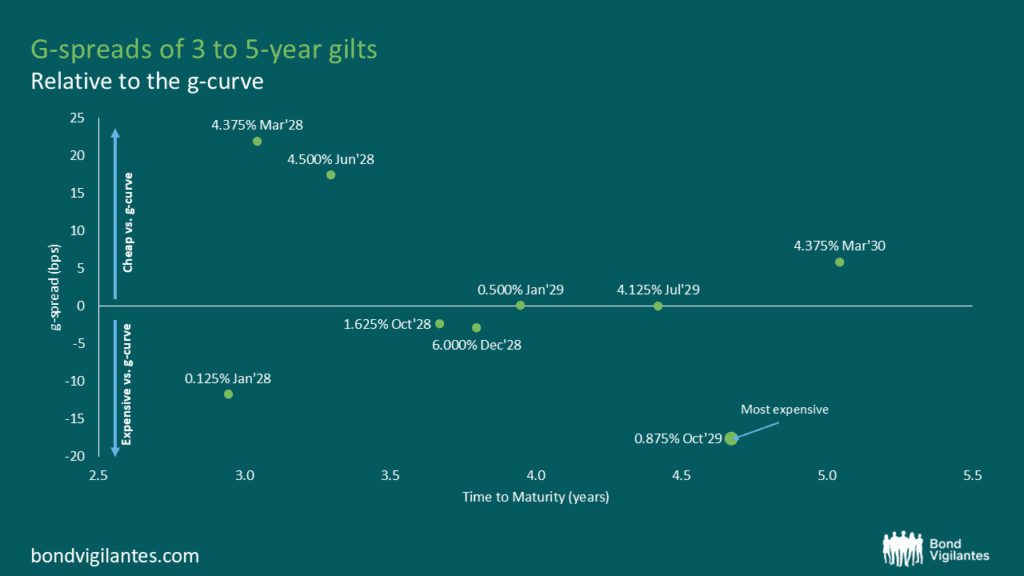

Consider ABN Amro’s senior bond issued on the 17th of February 2025 and maturing on the 24th of October 2029. Were that bond to mature just one month earlier, in September 2029, the reference gilt used for initial price talk (IPT)[1] would be the 4.125% July 2029 gilt.[2] However, since ABN’s bond matures in October 2029, the convention for choosing reference bonds requires the IPT to be based on a spread relative to the 0.875% October 2029 gilt. In most markets, that 3 month difference in reference bond maturity wouldn’t make much of a difference in pricing. In the UK, however, retail investors do not pay capital gains taxes on gilts, and as a result, low coupon gilts tend to trade well inside of the benchmark g-curve[3] (Rob Burrows wrote about this in a BV article last year). The chart below shows how low-coupon off-benchmark bonds tend to trade tight to the curve, while higher-coupon gilts tend to trade wide. In fact, the 0.875% bond has the lowest-spread of the bunch, trading 17.5bp through (i.e. below) the Bloomberg gilt g-curve.

Source: Bloomberg, as at February 2025

When seeing the initial “UKT + 95bp” IPT on this new issue, a casual investor might naturally have assumed the IPT g-spread would be close to 95bp. However, because the reference gilt was trading 17.5bp “rich” to the g-curve, the actual g-spread at announcement was closer to 78bp, not 95bp! To be sure, this bit of optic trickery has been going on for a several months and is certainly “within the rules” given the convention for how reference gilts must be chosen for new issues. Nonetheless, it’s a nuance investors need to be aware of.

We suspect most UK institutional investors are aware of it and make the necessary adjustments when comparing new issues with existing bonds, but there’s some speculation that less sophisticated or foreign investors who are less active in the UK market may not make such adjustments. This could potentially help the bonds price tighter than they otherwise would, so it’s not surprising that bookrunners would suggest the option to issuers. It’s hard to quantify the benefit, if any, these issuers may gain from it, but if there were none at all, would they continue to issue bonds with odd initial tenors benchmarked off lower-spread gilts? I don’t think so.

[1] The preliminary price range provided by underwriters to gauge investor interest before the final pricing of a bond issue.

[2] Were the bond a traditional 5-year, it would have priced off the much longer maturity, and higher yielding, October 2030 gilt.

[3] G-curve is the yield curve of government bonds, which serves as a benchmark for evaluating the relative value and pricing of other fixed income securities in the UK market.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.