From Dollars to Dinars

The US dollar has long held its position as the world’s dominant reserve currency, underpinning global trade and serving as a safe haven during periods of financial stress. This stability provided emerging markets (EM) with a reliable anchor for external borrowing, with the modern EM debt market beginning to take shape following the introduction of Brady bonds in 1989.

Named after then US Treasury Secretary Nicholas Brady, these instruments were initially designed to help Latin American countries restructure defaulted loans into tradable securities backed by US Treasury collateral. By transforming illiquid bonds into standardised, marketable instruments, the Brady Plan not only resolved a major debt crisis but also laid the foundation for a broader, more liquid EM debt market.

Emerging market economies that issue debt in US dollars (USD) remain heavily tethered to the policy decisions of the US Federal Reserve (the Fed), often at the expense of their own financial autonomy. This dependency, at times, has meant that when the Fed adjusts interest rates to manage domestic inflation and other matters, EMs can experience significant capital outflows, leading to currency depreciation and heightened financial instability.

While issuing in USD has granted EMs access to deeper capital pools and helped reduce borrowing costs, it has also exposed them to external shocks beyond their control. The reliance on dollar-denominated debt has eroded the agency of local governments, leaving them vulnerable to decisions being made in the US.

The 2013 Taper Tantrum remains one of the clearest illustrations of how vulnerable EMs can be to shifts in US monetary policy. When Fed Chair Ben Bernanke signalled plans to taper the Fed’s easing program, it triggered a sharp rise in US Treasury yields. Investors rapidly reallocated capital away from EMs, leading to widespread capital outflows and financial stress.

The impact was particularly severe for the so-called “Fragile Five”, India, Brazil, South Africa, Indonesia, and Turkey, whose economies were exposed due to high levels of foreign currency debt and relatively low foreign exchange reserves. As currencies depreciated, EM central banks were forced to intervene, often by raising interest rates to defend their currencies and stem further outflows. These defensive measures tightened domestic financial conditions and slowed economic growth, despite conflicting with local economic priorities.

This episode highlighted the structural vulnerability of EMs borrowing in USD as when US rates rise and local currencies weaken, the cost of servicing external debt increases sharply. In some cases, this dynamic contributed to debt crises. More broadly, it underscored the reduction in sovereign monetary agency, as EM central banks were compelled to respond to US policy decisions rather than domestic needs.

Changing Tides

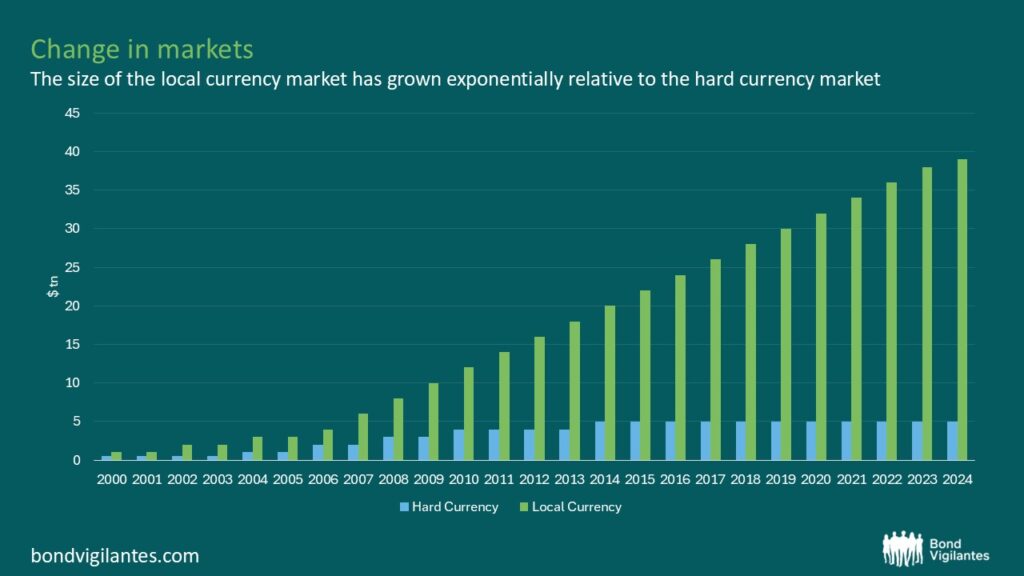

To reduce this vulnerability, policymakers have been shifting their attention towards local currency markets, whereby they issue debt in their own currency rather than in USD, in an attempt to give back powers in dictating their own policies. This, in turn, will give countries more say in their economic outcomes. To that extent, the local currency market has grown significantly in recent periods.

A material part of the local currency market expansion has come from Asian issuance, with China driving a significant portion of this. Notwithstanding this, even on an ex-Asia basis, the trend very much remains. The below chart highlights the change in market sizes of emerging market debt across hard and local currency.

Source: M&G, Bank of America. December 2024

As already alluded today, the additional autonomy helps countries stabilise their inflationary trajectory, economic growth, and employment levels. It also comes with the rather significant benefit of being better placed to manage global shocks.

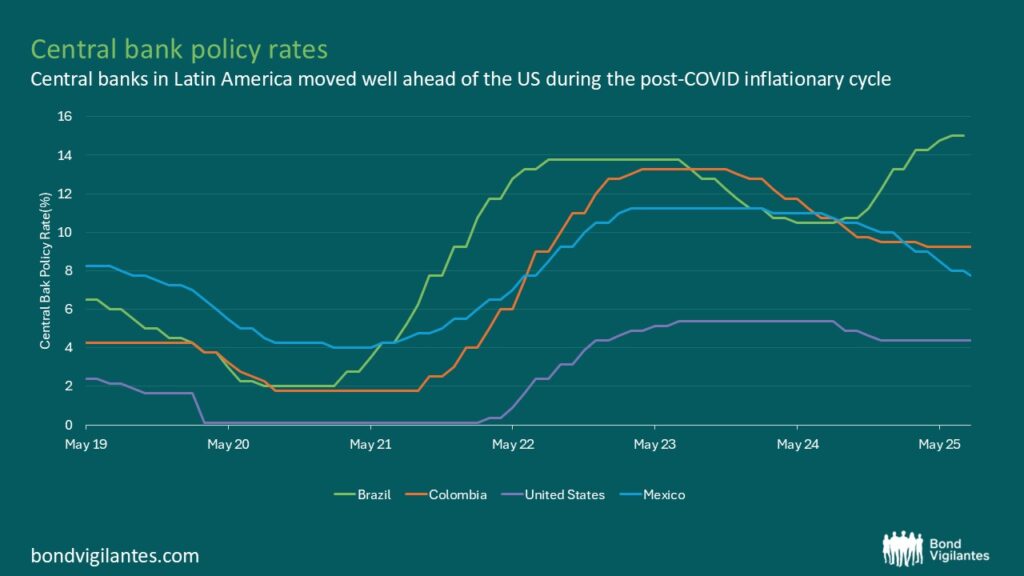

A fairly recent example highlighting this comes from central bank behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic, whereby several central banks around the world acted swiftly to tame inflation, implementing measures well ahead of the Federal Reserve (Brazil’s central bank raised rates a full 12 months before the Fed did).

Source: M&G, Bloomberg, as at 31 July 2025

Their proactive and successful interventions have demonstrated increased credibility and independence, showing that they no longer wait for the Fed’s lead to address economic challenges. This increase in autonomy has not gone unnoticed and has given strength to the argument that EM central banks now have more credible monetary policy.

Recent trends also underscore this shift. Central banks in countries like India and Indonesia have exercised greater independence, cutting rates even as the Fed has paused throughout 2025 so far. Indonesia’s flexibility, for example, stems from its decades-long transition away from hard currency borrowing toward local currency financing, which has empowered its central bank to respond more nimbly to domestic needs.

It would be wrong to suggest that this trend equates to the USD’s status of the global reserve currency coming under pressure. But as more EMs build credible local currency markets, we’re moving toward a more balanced global financial system, one that is less dollar-dominant and more regionally diverse. Arguably, this should make the global system more resilient.

Furthermore, the relationship with the dollar is still complicated. Many EMs still need to hold enough USD reserves to service external debt. And printing local currency to buy dollars can quickly spiral into inflation, just ask Argentina and Bolivia, who are recent case studies highlighting how quickly reserves can vanish when hard currency obligations mount. So while local markets offer more autonomy, exchange rate management remains a critical piece of the puzzle.

The Price of Autonomy?

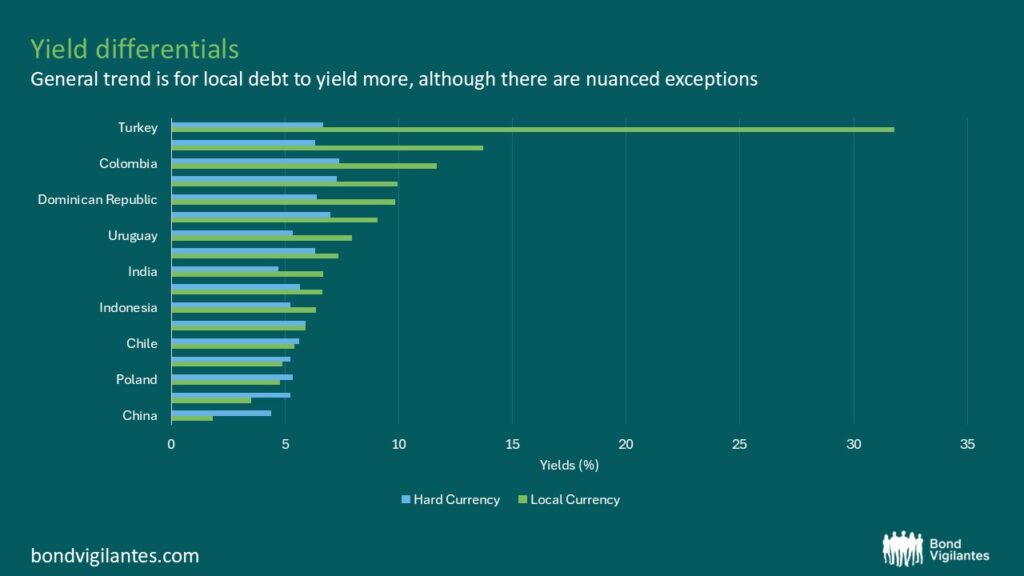

This autonomy does come with a cost, however. We would typically expect debt issued in local currency to yield more relative to its hard currency counterparts, so that investors are appropriately compensated for currency risk and the inflationary background within the issuing country. But the reality can be more nuanced than that, as highlighted by the chart below, which highlights the current yield on a country’s debt issued in either hard, or local, currency.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg, JP Morgan as 17 August 2025

The yields on Poland’s hard and local currency bonds offer an exception to what we would expect, insofar as local currency bonds actually yield less. One of the reasons for this is Poland’s economic strength, with its macro stability, moderate inflation, and institutional alignment with the EU building enough credibility to compress local yields. Furthermore, on a more technical related note, local currency bonds are often issued with shorter maturities than their hard currency counterparts. This, in turn, also reduces the yield on local debt as investors price bonds over a shorter time-frame, minimising the potential impact of inflationary and currency-related noise.

Brazil sits at the other end of the spectrum in this regard, with the spread of local currency over hard currency standing at around 8%. That premium, despite there being a shorter tenor, reflects the higher levels of inflation, FX risk, and lower credit rating. For an investor, however, it offers a notable yield pick-up.

China offers an even more unique situation. Local currency bonds yield less, but actually have a longer weighted average life than their hard currency equivalents. The reason for this is driven by the incredibly strong domestic demand and tight policy control designed to anchor local yields, whereas global investors price hard currency debt based on their perceived risk.

Notwithstanding some of the nuances, the higher yields on local currency debt typically appear more costly, but when weighed up with the benefits, it is a fairly savvy move. When issuing in their own currencies, EMs reduce their external vulnerabilities, particularly relative to the US dollar and Fed monetary cycles, which, as mentioned, has been a significant driver of financial stress in the past.

Moreover, developing a deep and liquid local bond market fosters financial stability and resilience over the long term. It broadens the domestic investor base, and encourages institutional development, whilst increasing reliable funding channels during periods when access to hard currency markets may be constrained.

And so, whilst the upfront cost of higher yields can seem significant, the structural benefits to economies within EM make local currency issuance a critical part of fiscal management for many emerging economies.

A local pivot

Ultimately, the evolution of EMs moving away from being largely dependent on the dollar to being able to better utilise local currency markets highlights a pivotal shift. Initially, hard currency debt opened doors to global capital but came with the cost of anchoring EM policy to external monetary cycles. the growing depth of the market reflects a growing confidence in domestic matters, but there is still a long way to go, with foreign ownership of these bonds still being relatively low.

However, as central banks demonstrate greater independence and credibility, and as investors continue to seek new opportunities, local currency debt should stand to benefit and become more widely used within global portfolios. This doesn’t signal the end of dollar dominance, but it does show that EMs are increasingly able to set their own rules.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.