You don’t expect any inflation in Europe? The Germans do. Look at their housing market!

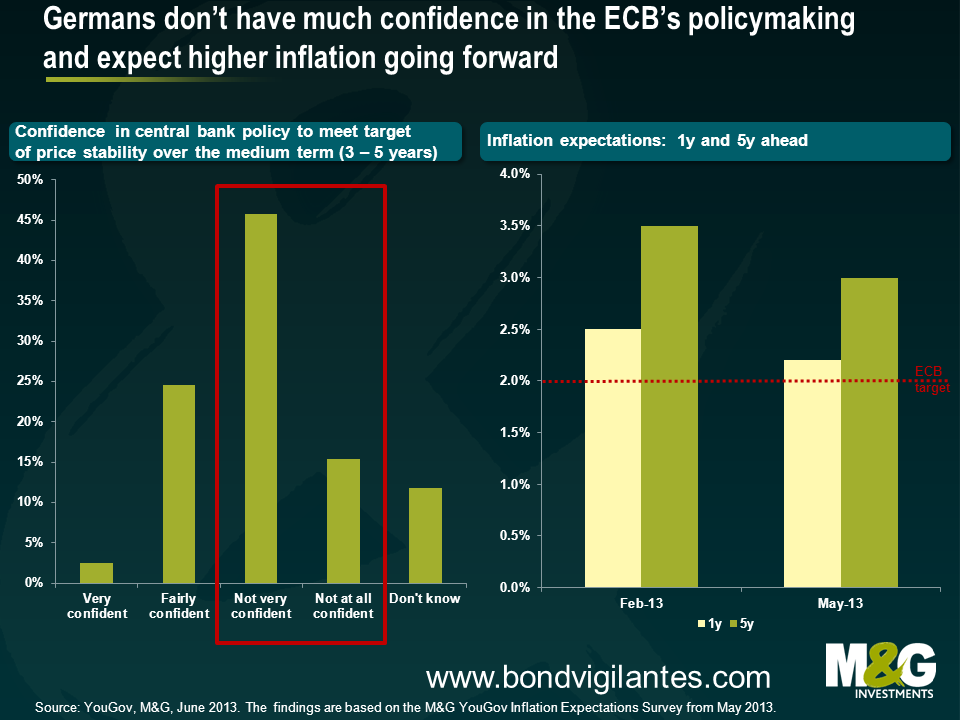

Being a German abroad, I am very aware that one never runs out of German stereotypes to discuss. One of the stereotypes is the German obsession with price stability and fear of price instability. The latest results of the M&G YouGov Inflation Expectations Survey indeed confirm the current worry about inflation amongst the German public. The chart below suggests that Germans have an exceptionally low confidence in the ECB’s policymaking and expect inflation to be above the two per cent target both one year and five years ahead. Although we have seen a declining trend from February to May 2013, inflation expectations over the medium term in particular remain significantly elevated.

It seems to be clear that Bundesbank president Jens Weidmann’s metaphorical use of Goethe’s figure of the devil, Mephisto, as well as other critical remarks by the Bundesbank, may not have helped the German public’s confidence in the ECB’s ability to deliver price stability. However, it looks to me that there are more factors at play that currently shape the German expectation of rising inflation. Earlier this year, I shared my observations on wage dynamics in Germany and concluded that we could see some notable real wage growth in 2013.

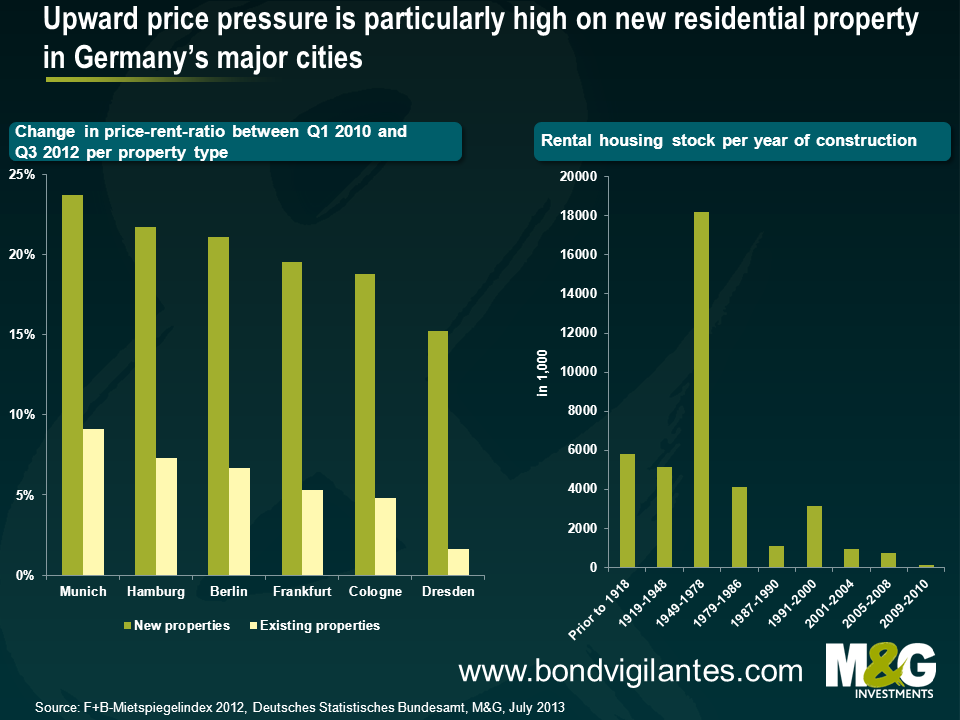

But Germans are also experiencing another form of inflation that is different to most parts of Europe: rising house prices. While an increasing house price level is a form of asset price inflation rather than consumer price inflation, it also has wider implications for the general consumer price level. Firstly, property owners tend to pass on the higher mortgage refinancing costs through increases in rents. For instance, rental costs form a significant part of the German CPI basket (21 per cent) and therefore feed through into the general inflation number. Furthermore, in an environment of rising house prices, homeowners have a greater ability to increase consumption spending by borrowing against the higher asset valuation (although this does not appear to be happening given the lack of German credit growth). The chart below shows that German house prices have increased on average by 10 to 20 per cent from 2007 to 2011, with significant variation dependent on the residential area and property type. The DIW Institute finds evidence that this trend has continued and seems to be accelerating in German cities. Prices for flats in Berlin, Munich and Hamburg are estimated to have risen by around ten, seven and six per cent annually since 2007.

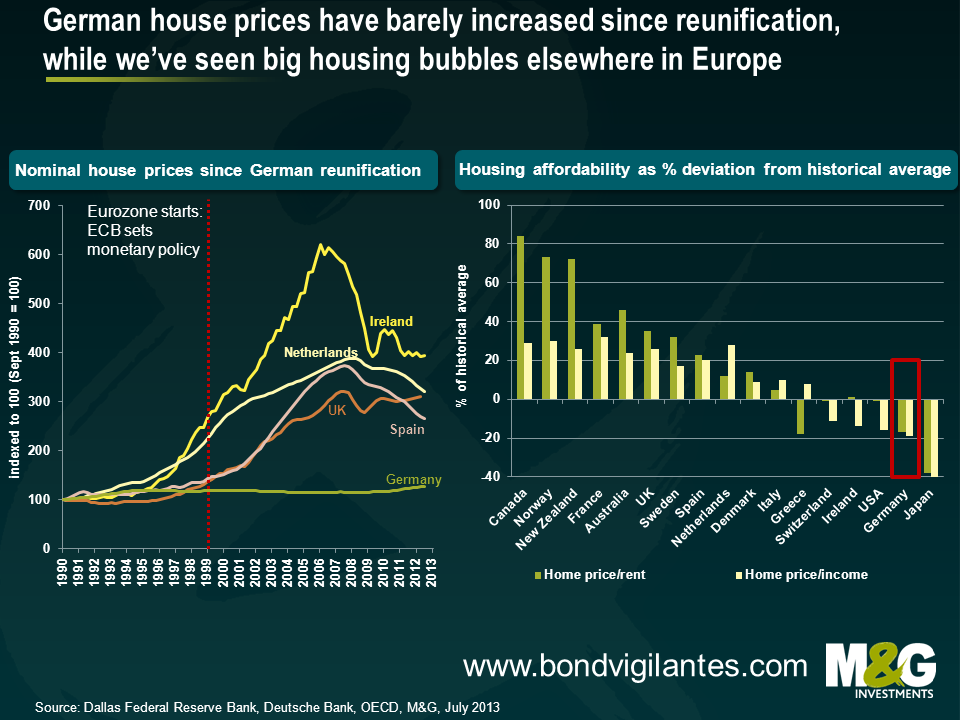

The German housing market history stands in stark contrast to many European countries. ECB interest rates were too high for Germany up until 2008, but too low for the high growth economies of Ireland and Spain. Germany therefore did not experience the credit-induced property boom in the 2000s that subsequently sent the Irish and Spanish homeowners into financial difficulties. Irish and Spanish house prices have fallen considerably since their housing bubbles popped, but they still look high compared to pre-Eurozone levels. The Netherlands is the most recent example of a European economy that is struggling with a bursting housing bubble, with house prices 9.6 per cent lower year on year. The downward trajectory of the Dutch economy seems to be accelerating and is certainly one to keep a very close eye on. Remarkably, house prices in the UK are back to pre-crisis level – and the government’s ill thought through “Help to Buy” scheme might fuel prices even more.

Although German house prices have recently begun to climb, if you expand your time horizon to the point of German reunification in 1990, it becomes evident that the general German house price level has barely increased over the past 23 years in nominal terms, let alone in real terms. The recent increases in house prices at the national level and in cities like Berlin have started from a very low base, and there is significant potential for further increases if you consider that housing affordability, as measured by the home price-to-rent ratio and home price-to-income ratio, is still significantly below the historical average. At the same time, housing in the UK, Spain and the Netherlands remains expensive compared to historical levels. So if refinancing rates are cheap in the current low interest rate environment (the ECB’s monetary policy is arguably too loose for Germany) and house prices are on an upward trend, wouldn’t you expect the Germans to invest in new homes?

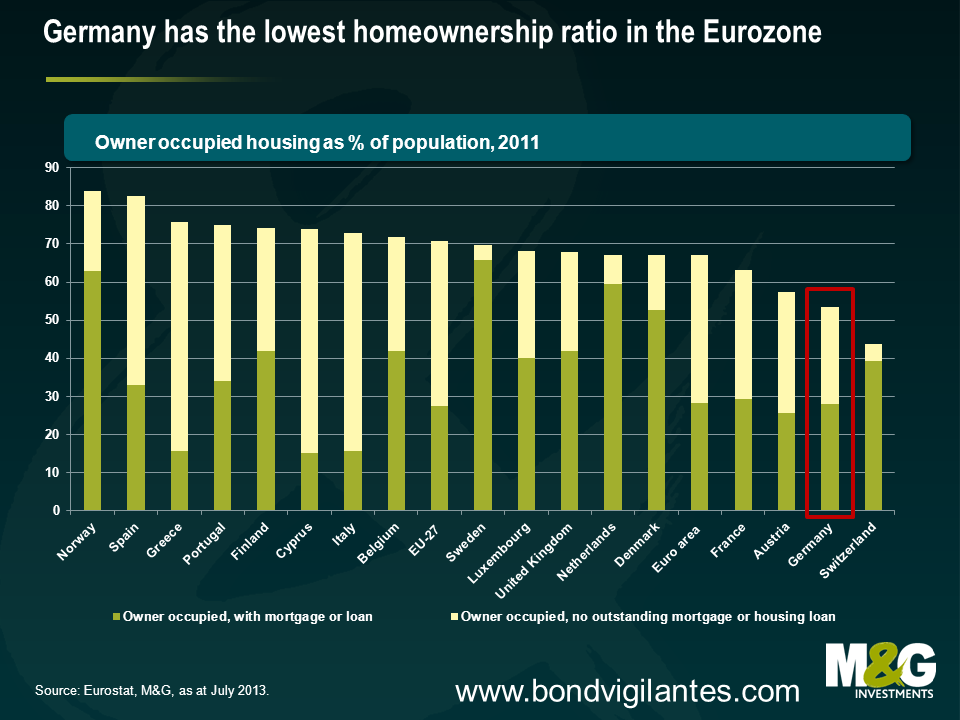

Well, so far they haven’t really done so, at least not by European standards. Homeownership has increased in recent years, but still remains significantly below the levels of the rest of Europe. Only about half of the population lives in their own houses (the German census from 2010 suggests that homeownership stands at 45.7 per cent, while the Eurostat figures above are around 8.7 per cent higher). This compares with an average ownership level of around 70 per cent in Europe. Let’s have a look at some of the reasons why Germany has not seen a property investment boom yet.

Homeownership is less widespread for a number of historical, cultural and economic reasons. For instance, domestic credit lending has been fairly strict and, as a result, Germany has not seen a mortgage boom which inflated the US, Irish and Spanish housing bubbles (sadly tight lending standards did not apply to overseas lending, as illuminated by the 2008 crisis and more recently by German banks’ exposure to Detroit’s default). The average initial repayment rate stands at around two per cent currently and the average loan-to-value ratio remains below 80 per cent. To put this into context, loans without an initial repayment rate and a loan-to-value ratio of more than 90 per cent were very common in the US prior to the financial crisis. Also the recent mortgage loan growth rates of 1.2 (2011) and 0.3 per cent (2012) show no evidence for a hot property market.

Historically, the German housing culture has been to rent a property, and it takes a long time for culture to change. The predisposition to rent can be traced to the policy measures by the German government after WWII. The government responded to the acute lack of residential property by highly subsidising social housing instead of providing cheap funding for new private home builds. The chart above shows that German housing investment saw an enormous boom from 1949 to 1979 and that most of the current rental property stock dates back to this period. Many of the German baby boomers were brought up in rented flats and houses – it has been the norm, not the exception. However, the chart also presents strong evidence that it has become significantly more expensive to rent in the last 3 years, particularly in more prosperous urban areas. Property developers have managed to push up rents for new residential property by more than 20 per cent. The German government released a report in October last year suggesting that the demand for urban housing in the strong economic regions remains high due to continuous migration flows from the economically weaker regions of the country. It is estimated that Germany faces an annual construction demand of 183,000 residential apartments until 2025.

Given the considerable demand for new urban housing and the current favourable investment environment, German house prices may be set to rise for some time. In particular, price inflation for new property developments in prosperous urban areas, such as in Hamburg, Stuttgart and Munich, seems to be baked in the cake for the next years. However, a housing bubble is not in sight yet as we are not experiencing any excessive credit growth given that banks remain capital constrained, and valuations are not in bubble territory as housing affordability still looks reasonable relative to historical levels. Germany is currently heading for a natural adjustment of its house prices, and this may be a positive development for the Eurozone. That is, an increase in property investment would subsequently lead to a decrease of the excess German savings rate, bring down the enormous current account surplus and therefore help the Eurozone rebalancing.

However, German government interference might distort the natural adjustment process of German house prices. Decreases in rent affordability are a real concern in the German public at present. Consequently, not only the left-leaning German parties, but also Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats (CDU) have agreed upon a “Mietpreisbremse” in their electoral manifesto, a policy to cap the maximum rental growth rate that can be imposed if a flat or house is re-let. The FDP, the CDU’s coalition partner, seems to be the only major German party that doesn’t support such a policy initiative. Therefore, it is very possible that we could see some sort of “Mietpreisbremse” after the general election in September. This policy would potentially have a disinflationary impact. Subsequently, this might be reflected in the public’s medium term inflation expectations which could then trend downward from the current elevated levels. Ultimately, the rental cap might also affect house prices. The prospect of being restricted in the ability to pass on higher prices and financing costs to the tenant in form of higher rents could make property investment less attractive. This argument may be countered by suggesting that a shortage of supply could cause a squeeze in the German property market and actually keep pushing prices up if residential investment doesn’t pick up. That is, Germany could see further asset price inflation, but a slowdown of the rental growth rate and, consequently, of CPI inflation. Against this background, it’s definitely worth to keep an eye on both the German housing market and inflation expectations!

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

17 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox