Eskom, Pemex: two distinct stories but a similar root of problem

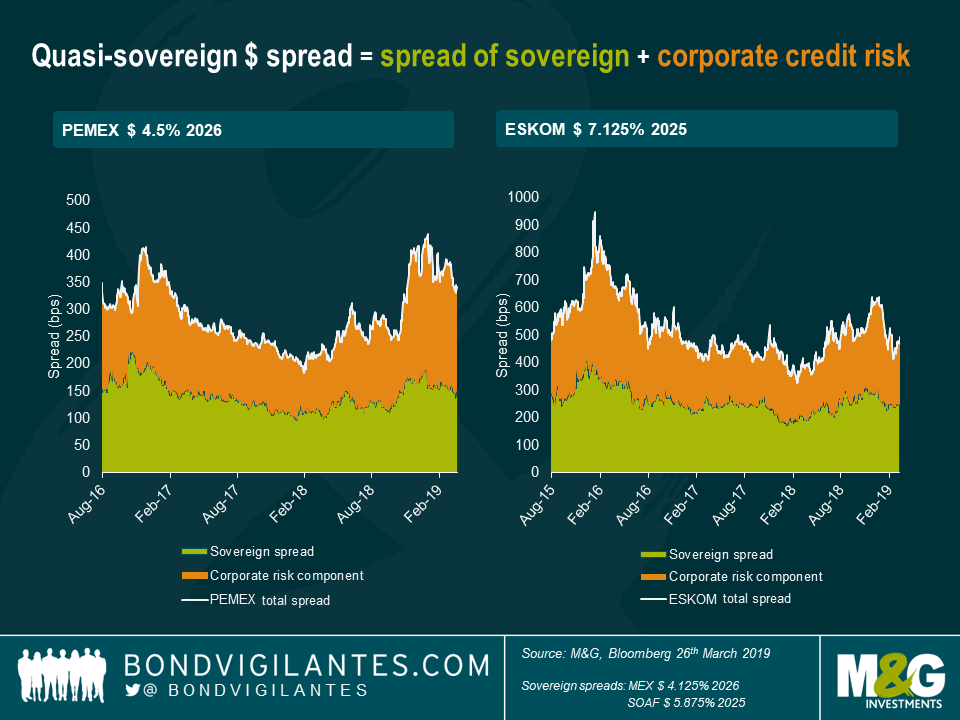

Fully government-owned corporate bond issuers (or quasi sovereigns) are one of the most interesting areas of emerging market debt investing, due to the hybrid nature of their credit risk: partly corporate credit, partly sovereign risk. Venezuela’s national oil company PDVSA is an example of what can go wrong, as it is in default. Bond investors are therefore currently spending more time looking at Pemex and Eskom, in order to assess whether they could follow a similar path in the future.

As Mexico’s national oil company, Pemex is strategically important for the country. Oil revenues contribute to approximately 20% of Mexico’s budget and Pemex is one of the largest employers in the country. Due to a lack of investment in its upstream segment for years, oil production has been heading south at a significant pace; cash flows have suffered from the lower oil price since 2014 and a substantial tax rate (as the company is the cash cow of Mexico’s budget). Meanwhile, Pemex has continued to tap the bond markets to fund its sizeable and recurring cash burn (i.e. bond investors are effectively funding the Mexican budget through Pemex) due to the misleading “implicit guarantee” from the government. (The concept of implicit guarantees had been discussed in a previous blog here). Today, the company is facing refinancing risk as debt maturities pile up and investors have realised that the company is technically insolvent, with more than $100 billion of debt, enormous unfunded pension liabilities and a negative equity balance.

South-Africa’s Eskom runs more than 90% of the electricity market in the country. Rated BBB- in 2014, Eskom was investment grade a few years ago. However, given that the company under–invested and misallocated capital for a decade, it has come under huge financial stress in the past 4 years, as electricity demand stagnated and regulated tariffs increased at a lower pace than fixed costs. In addition, municipal arrears have soared and various corruption scandals at the top management level resulted in a lack of stable leadership for years (10 CEOs in 10 years). Throughout the period, financial costs increased materially and Eskom found itself generating just enough cash from operations to pay for its interest expenses. That meant all capex had to be funded inorganically. While the government provided cash injections for several years, the company also chose to incur debt. Eskom’s credit rating is now CCC+ and the company is said to be struggling to pay for coal procurement.

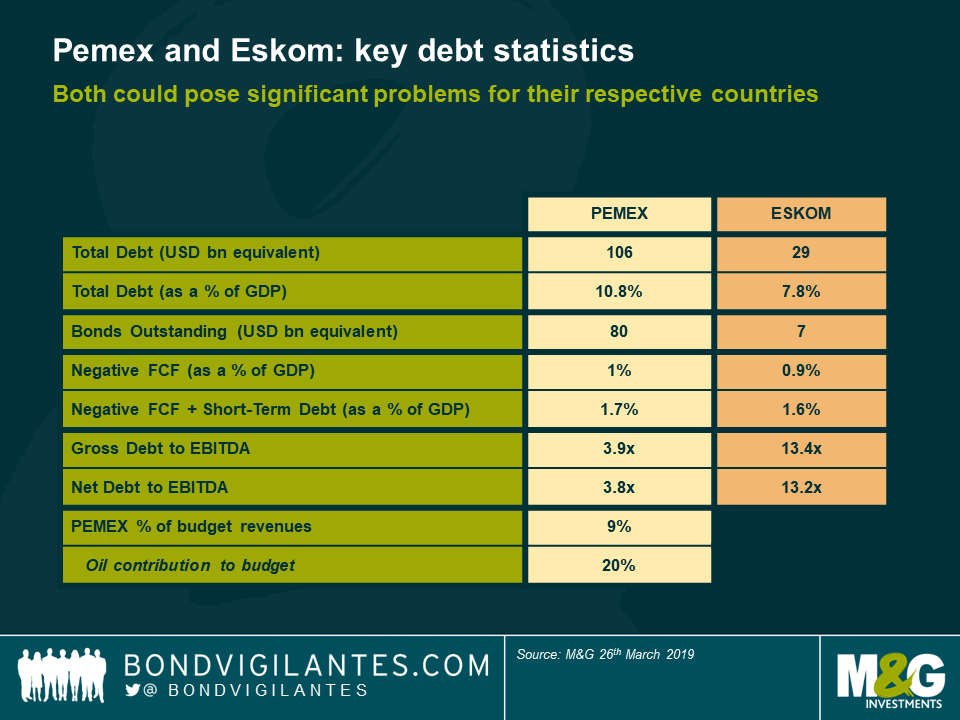

Two different countries, two different sectors but one common denominator: they are both fully-owned by their respective government and the above table shows the magnitude of the challenge for their respective countries. Both Pemex and Eskom are textbook examples of poor governance due to historical short-term political considerations that came at the expense of strategic investments which should have paid off well beyond any political mandates. Transparency is a critical element of governance. It holds management accountable and significantly reduces corruption risk. In my experience, emerging market fully government-owned corporate issuers in their vast majority have weaker transparency/disclosure than majority-owned and/or listed corporate bond issuers. But paradoxically, instead of taking this full ownership structure as a red flag, bond investors tend to discount the elevated governance risk with the lower probability of default, on the assumption that governments will always financially support their strategic assets. This is not a sensible way of investing in corporate assets. The fact that fully-owned quasi-sovereign bonds are part of the emerging market sovereign bond index (JP Morgan’s EMBI index), even when there are no sovereign guarantees, is not helpful and should be questioned. Any emerging market corporate asset analysis must encompass a sovereign risk assessment; if quasi-sovereigns were part of the corporate index they would be under much more scrutiny by corporate analysts.

Both Pemex’s and Eskom’s governments have recently come out with sovereign support packages which certainly will reassure investors (albeit to varying degrees) and reinforce their views that both companies are sovereign investments and hence face sovereign-like default risk. However, to date, the actual details of state support are disappointing and unlikely to move the needle. Along with sovereign support, improving transparency and governance might be key to restore investors’ confidence over time. But how do you do that? It is unlikely to come from a new government – we have all heard that story before. One of the most credible options is to partially list parts of their businesses to force those companies to adopt financial market reporting requirements and generally-admitted sound business practices. Eskom and Pemex are both strategic assets and it is understandable that the people of South Africa and Mexico want to retain their control, but it would take just a small publicly listed ownership to make these changes happen. Brazil’s national oil company Petrobras is publicly listed and majority-owned by the government of Brazil and is a good example of a transformational turnaround when a government accepts to partially step back on business strategy. Listing not only brings transparency, but also attracts private expertise that may bring checks and balances to political considerations, i.e. exactly what Pemex and Eskom have been missing for years, if not decades. Partial privatisation will make their bonds fall out of the sovereign index (expect forced selling pressure in this case) into the corporate universe and over time, would receive the necessary bond investor due diligence that they deserve. There is no perfect fix, but the short-term political cost of partial privatisation is likely to be more than offset over time by savings on sovereign support to poorly-run businesses.

The current political rhetoric in Mexico however makes any sort of partial privatisation unrealistic in the near term. Pemex roughly pays over 40% of revenues and 85% of EBITDA in tax and royalties, so an easy fix for the government would be to reduce tax to a “normal” level. In this way, the company could generate enough cash to organically fund its investment needs upstream, in order to revive production. But from a sovereign perspective, this may prove challenging as Pemex contributes to 9% of Mexico’s budget revenues, so the government would need to source revenue elsewhere. Tax collection is very low in Mexico and under President Lopez Obrador, new tax increases and spending cuts are unlikely. In the event that the Pemex situation doesn’t get fixed quickly, we estimate that Pemex’s cash burn will cost Mexico 1% of GDP per annum. Should Pemex not have access to debt markets for refinancing, the bill will go up to 1.7%. At this stage, Pemex may contemplate issuing fully and unconditional sovereign guaranteed bonds.

Eskom’s situation is arguably worse. Whilst its debt levels account for “only” 7.8% of GDP vs 10.8% for Pemex, Eskom’s underlying cash flow generation is deeply negative and cannot be fixed by a tax cut from the government or issuance of additional sovereign guarantees. A capital injection is therefore needed to operate as a going concern. The recently announced breaking down of the electricity sector with a separate transmission business might open the door to privatisation in the future and is a good step forward – definitely more credible than the Pemex support plan. However, the upcoming general elections will be a big challenge in order to implement any meaningful reforms in the short term. The total bill for South Africa may come at 1.6% of GDP p.a. in the next few years.

The Pemex and Eskom cases are today’s problem, but they offer great lessons for predicting tomorrow’s potential credit deterioration of emerging market fully-owned quasi-sovereigns. With that in mind, red flags exist in China where highly-rated state-owned enterprise issuers require a cautious approach by investors, as it often starts with weak transparency.

To read more on Quasi-Sovereigns in Emerging Markets, see our panoramic.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox