Two big questions: recession and inflation – part 2

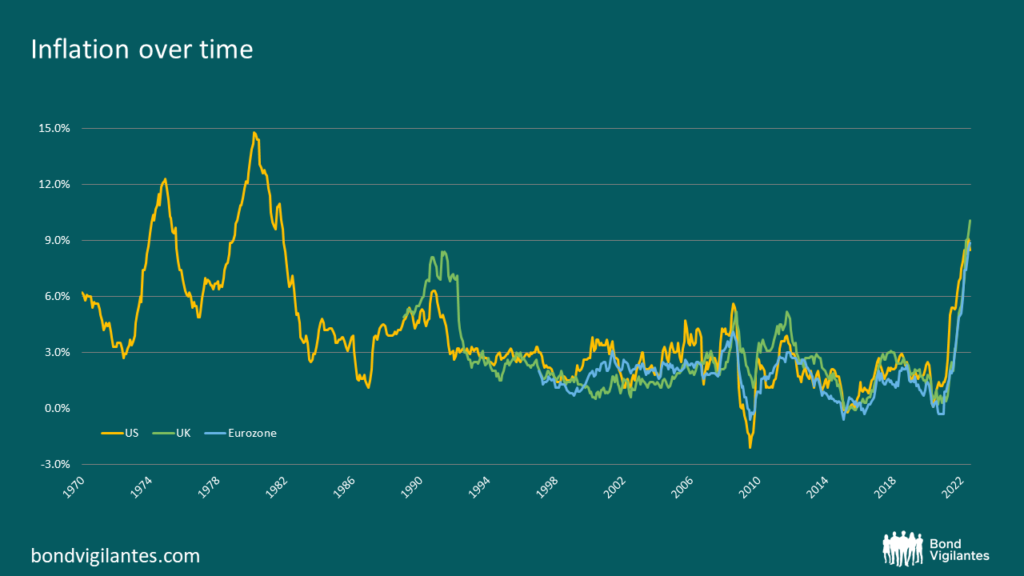

Following on from the recession blog we said we would discuss inflation: this is the big difference in the economic cycle this time around as illustrated in the chart below.

The common cause of the current inflation according to many commentators is the supply shortage, whether that be commodities, manufacturing or labour. Central bankers frequently have pointed to these effects: “Supply-side constraints have gotten worse,” said Fed Chair Powell at the end of last year. “The risks are clearly now to longer and more-persistent bottlenecks, and thus to higher inflation.”[1]

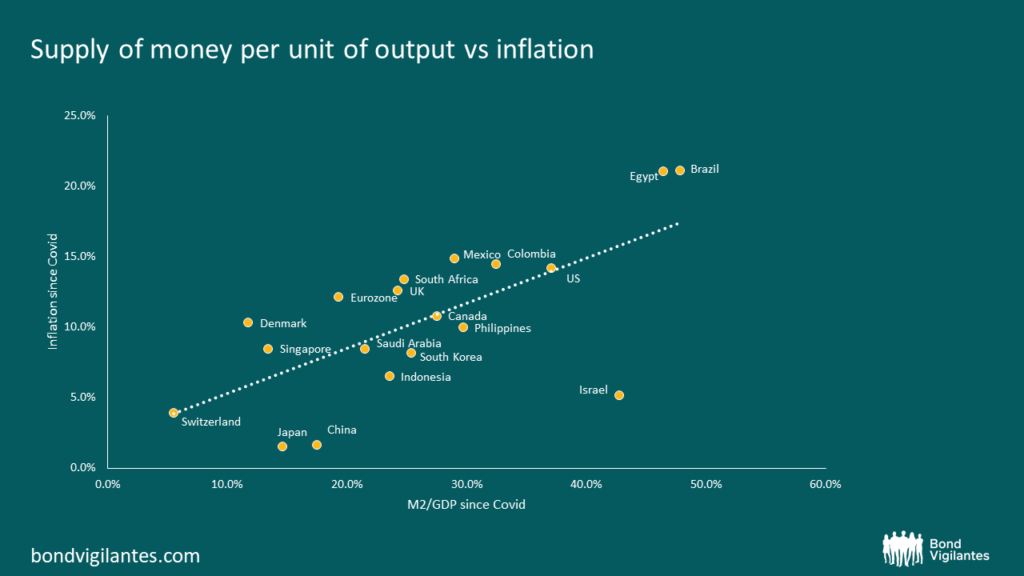

These issues contribute to the inflationary outcome: supply and demand matter. Inflation however is the balance of relative supply of money versus what that money buys. This is an area that central banks are not commenting on as much. We will explore this issue today.

Below shows a chart of the increase in supply of money per unit of output as measured by M2/GDP. Against this we plot inflation outcomes in the same economies. As the economic textbook would say, increasing the supply of money is a major influence on inflation. To put it simply, the supply drought in goods and services has been met by a deluge of supply of money. It can be argued that it is the excessive abundance of money that is contributing significantly to current inflation.

We have discussed previously the way helicopter money works. Central banks are now trying to return money supply growth to more normal levels and trying to collapse the outstanding monetary surplus by quantitative tightening. The central banks have 3 policy options to implement if they decide to clean up this flood of cash.

Firstly, they could simply let it dry in the sun. This would involve accepting the inflation they caused, and hope for no secondary inflationary effects embedding into the economy, primarily through changes in inflation expectations. This dovish policy would mean not altering the money stock and letting the impetus of previous policy simply die out.

Secondly, they could mop up the liquidity by doing some quantitative tightening so bringing future inflation under control at a faster pace.

Thirdly, they could implement a cyclone policy of rapid tightened by sucking back up as much money out of the economy as they dare. A rapid collapse in inflation would ensue but this cyclone approach would risk damaging the wider economy.

Central banks are likely to follow a pattern somewhere between the first and second option. This means inflation will persist but will then fall with the usual monetary lag, as indeed it surged with the usual monetary lag. Inflation will therefore likely be temporary but the definition of the period of ‘temporary’ is in central bankers’ own hands.

The current inflation conversation is based around supply constraints of goods and services. Maybe the debate should be more about supply constraints of money being implemented to bring inflation down. Central banks can get inflation back to target – it is a question of how quickly they decide to do it.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.