Can developing country debt and climate emergency problems be solved in one go?

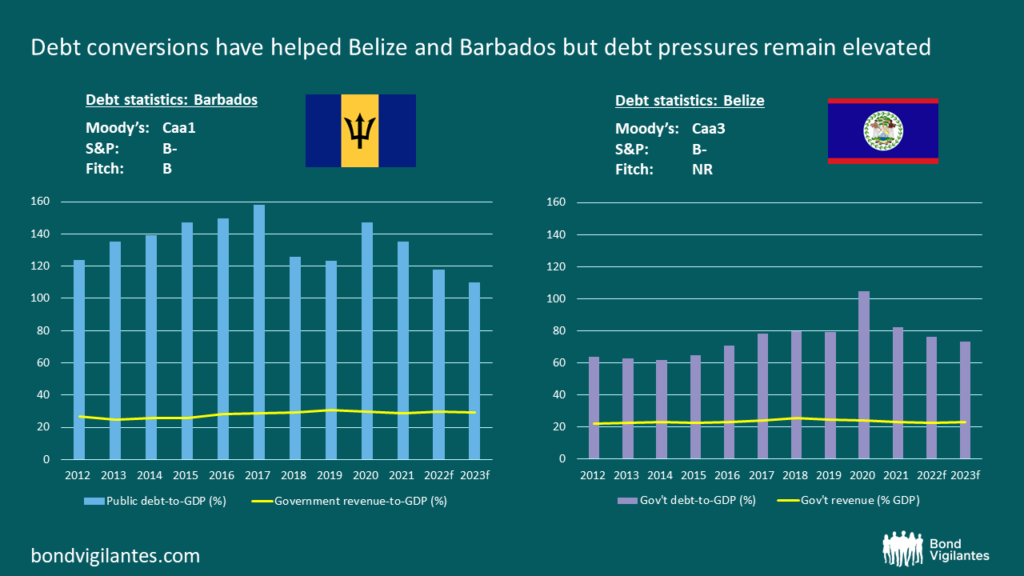

Around COP 27, there has been renewed interest in climate-debt swaps, green bonds, and blue bonds. Sovereign debt conversions in Belize in November 2021, and Barbados in September 2022, are frequently cited examples that have eased debt pressures while increasing environmentally sound investment.

Whether we talk of climate adaptation, climate mitigation, preserving biodiversity, or achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), there are massive investment needs. Taxes, domestic investment, and foreign aid all fall short of the financing required to meet investment needs. Ideally, there would be an abundant flow of long-term capital from, into, and among developing countries that did not create any debt. However, this is not the reality. So, to tackle the climate emergency while raising standards, developing countries need a greater share of global capital.

Thankfully over the past 15 years some rapidly growing developing countries have gained access to global markets. Where debts are kept sustainable there are growing pools of sustainable financing, that can be tapped once credible environmental or social investment frameworks are put in place.

Where developing countries are already facing debt problems it is going to be an uphill struggle to attract sufficient climate investment. Worse is that without that investment, especially in climate adaptation, such countries will be left vulnerable to climate shocks, with knock-on effects to their debt sustainability. To escape this doom loop, innovation is needed.

Debt conversions: where the magic happens

A recent source of optimism is found in the $364 million debt conversion in Belize and the $150 million one in Barbados, that followed a trail-blazing $15 million blue bond issued by the Seychelles in 2018. These conversions are a huge help and illustrative of what can be achieved, but we should not get too carried away. As heavy debt burdens remain after these conversions, they transformed just a segment. And much more environmental investment is needed. This begs the question: how can such conversions become bigger and be applied more broadly?

Source: IMF, M&G (October 2022)

Lesson 1: The need for credit enhancements

As both Belize and Barbados had defaulted on their external debt in recent years, they were struggling with attracting new investment. The Belize and Barbados transactions were made possible by credit enhancements. In Belize’s case, political risk insurance provided by the US government helped convert defaulted debt into an investment grade debt instrument. In Barbados’ case, guarantees did a similar job. Without these credit enhancements, the reduction in the debt burden would not have been possible. Somebody needs to be generous with their financing or balance sheet for these conversions to happen.

Lesson 2: The need for a credible sustainable investment framework

Without credible investment in the oceans the credit enhancements would not have been offered. For a repeat or scaling-up of the support, the credit enhancer needs to be rewarded by a virtuous and credible use of proceeds. Such credibility requires countries to build a solid framework for ensuring the new money is invested well. A good framework includes clear quantitative targets, data you can trust, ongoing monitoring of progress, regular reporting, clear information on how money was invested, and external independent verification. The framework must be made public and easy to find.

More broadly, a country that can convincingly set out its ESG credentials will be able to attract more and better capital, whether from bond markets or in the form of direct investment, private equity, portfolio flows, or official sector support.

Lesson 3: The continued need for wider debt management reforms

The conversions alone won’t secure debt sustainability. In my book on African debt I articulate solutions for better borrowing. The ideas can be applied more broadly to developing countries on other continents. While there is no silver bullet, there are steps that can be taken to help secure debt sustainability. Most debt problems tend to be a symptom of another problem. Countries might not be using the proceeds of borrowing well (that is, there is an investment problem). There could be insufficient resources to deliver public service and service debts (that is, a revenue problem). Or there might be a mismatch between foreign currency earnings and external debt servicing costs, an export problem.

Lesson 4: Encourage and don’t deter private investment

At the onset of the COP, the managing director of the IMF, Kristalina Georgieva, said that: “most important here, and in the months to follow, is to work relentlessly to create opportunities for private investments to take place in the developing world”. Georgieva said: “More private investments are needed to help developing countries to meet their climate change targets” (REF 4).

However, at an operational level it seems that the IMF has swung the pendulum from nurturing developing countries access to global markets, back towards aid dependency. This ‘you should only borrow concessionally’ approach makes sense for some of the poorest countries, where those official flows can be scaled-up (as multilateral banks can use their balance sheets more creatively to lend more in future). But for larger middle-income countries a more sensible equilibrium position is needed. A restoring force is needed, otherwise climate targets will be missed and a greater future cost incurred.

Case study: Zambia

Zambia is a country with extremely strong green credentials. It has historically emitted next to zero greenhouse gases, it generates the majority of its electricity from renewable sources, and it is a leading producer of metals like copper that are essential for the transition to net zero. Zambia’s problem is that it borrowed too much between 2015 and 2019, invested the proceeds inefficiently, and defaulted in 2020. The IMF’s board has agreed to support Zambia stabilise its economy. In doing so the IMF has a set an aggressive target for debt reduction that Zambia must now try and get from its creditors. The IMF decided that Zambia’s public debt must not only reach ‘moderate risk’ from ‘high risk’ but must do so by a large buffer. This stance helps push for a smaller debt load in the coming years, but risks souring investor sentiment at a time when social and environmental investment is crucial.

A better approach for Zambia, and others in a similar crunch, would look at both debt problems and investment needs simultaneously. Credit enhancements could be used to help crowd-in well targeted climate investment. A larger debt reduction would also be easier to justify if there were clear new green or ESG investments. Zambia’s finance minister announced the government’s wish to issue a maiden green bond in the 2023 budget. Supporting this would be a better first step to securing the climate investment and adaptation Zambia urgently needs.

Summary

Efforts that reduce poorer countries’ debt pressures while investing in our environment are crucial and compelling, as are the recent debt conversions, but there is still a lot of work to do. Innovation is needed to reach a meaningful scale of debt conversion for countries experiencing debt problems, while reforms are needed to ensure that developing countries can secure debt sustainability.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.