The last lonely Brady bonds: would more make sense?

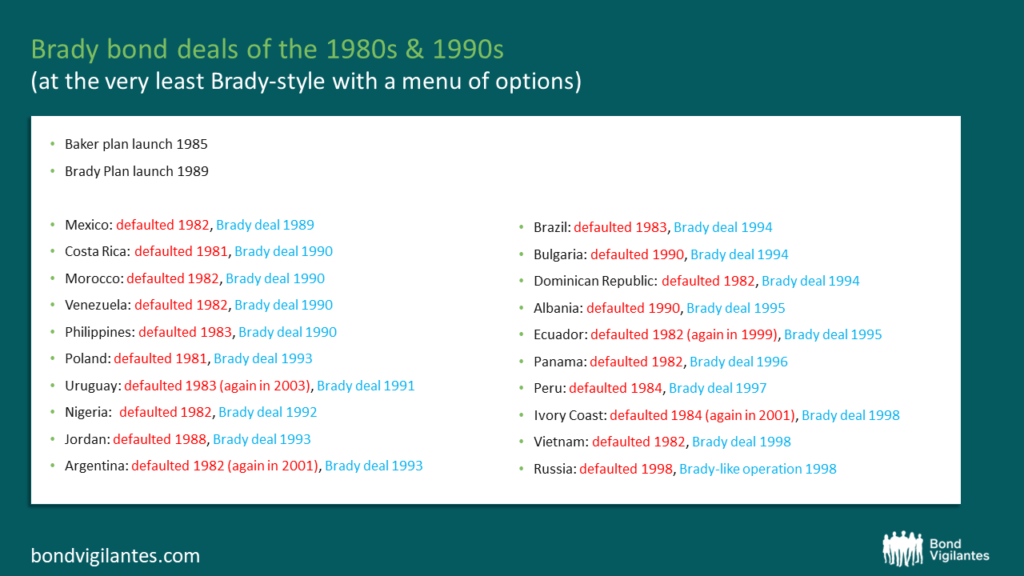

The Brady scheme was the eventual fix to the 1980s emerging market debt crisis. While most Brady bonds have been called or matured, two lonely bonds of reasonable size remain trading in global bond markets. Albania’s $225 million Brady bond was issued in 1995 and matures in 2025. Vietnam’s amortising Brady bond, issued in 1998, has its final payment scheduled in 2028. Each bond is backed by US Treasuries.

These bonds would only be a historical relic, were it not for recent talk about the need for a Brady plan 2.0. So here we discuss whether such talk is warranted.

What was the Brady plan?

Many emerging market sovereigns defaulted in the 1980s. The dominant commercial lending in that cycle had been loans made by international banks. So a fix was needed not only to help the countries deep in debt crisis, but also because the US banking sector was at risk.

Prior to the Brady scheme a few rounds of loan rescheduling helped kick the can for a year or two at a time, but without a reduction in the face value of what was owed the debt overhang persisted. This smothered economic recovery, resulting in a lost decade badge for the period. The Brady plan was launched to: (i) turn illiquid bank loans in to tradeable bonds (so the international banks could get them off their books); and (ii) support struggling sovereigns with a debt reduction.

By the way, one of my favourite books on emerging markets is Dance of the Trillions, by David Lubin that covers this period in detail.

Do we need a Brady-type rescue plan?

At the stronger end of the emerging markets spectrum are countries that have sensibly shifted to borrowing mostly at home, in their own currency, and have decent stockpiles of reserves. So for starters not all emerging markets are in debt trouble. However, too many emerging markets remain overly reliant on foreign currency debt, hence the worry.

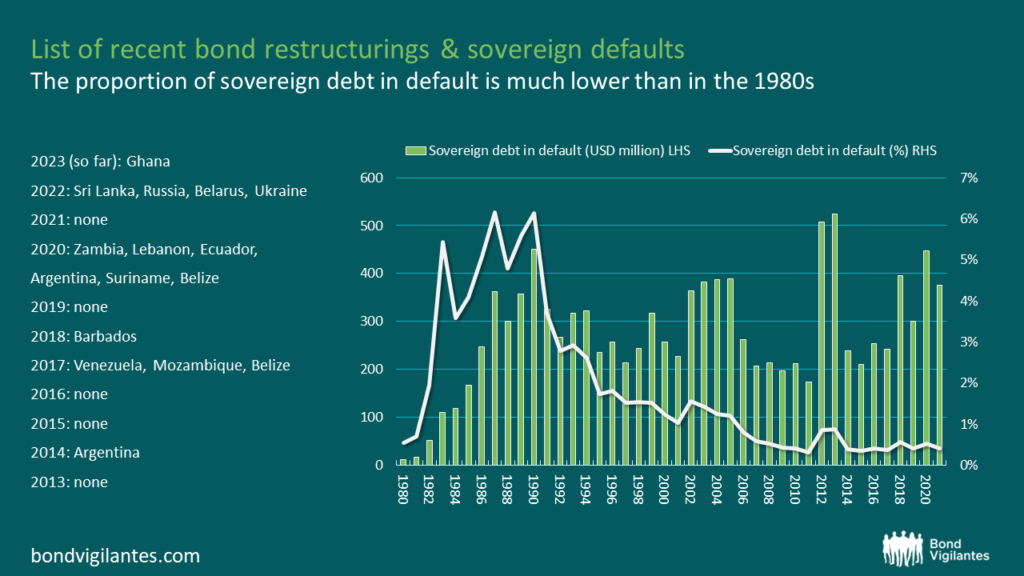

Since the pandemic hit there have been a string of sovereign defaults. While these are each tragic events, they don’t sum to a systemic crisis. Further unlike the 1980s there are no worries about the global financial system, as international banks are not at risk. In 2021 just 0.4% of sovereign debt was in default versus 5.4% in 1983. Nonetheless, given the recent increase in global interest rates, plus growing debt risks over the past seven years, there is a worry that more countries might default.

A few defaults at a time and the norms for sovereign debt restructuring can provide a work out (even if at a sluggish pace). But, if the number of defaults overwhelms those norms and countries are left in default for many years, then a more formal debt reduction scheme might be needed.

Lessons from the Brady era?

The Brady Plan is generally viewed as a success, in that it helped many emerging economies emerge from a deep, lengthy debt crisis. But there are lots of things that can be done better, and circumstances that would make the next crisis different to the 1980s.

These are the lessons I draw:

- Hair was cut. There was enough debt reduction to get the economies in default going again. Although not enough for some countries as they went on to default on the Brady bonds (for example Uruguay, Ecuador, Argentina, and Ivory Coast).

- Delays and false starts. It took many years to get there. For example, Mexico had to wait 7 years between its default and the launch of the Brady plan. Also, the similar Baker Plan failed in 1985 prior to the Brady plan getting legs in 1989.

- Flatter the official financier. The Brady Plan was named after the US Secretary of Treasury at the time (as was the Baker plan), as the USA championed the scheme.

- A good stick. The main commercial lenders were international banks in the 1980s, so they could be pressured into “voluntarily” accepting the debt exchange by their regulators. The current diversity of commercial creditors, given this cycle has been about bonds not loans, means there’s more of a twig than a stick.

- A tasty carrot. The collateral made the Brady bonds attractive. This could only be afforded by the sovereigns in default, because the multilaterals provided concessional loans for its purchase. As with most debt workout schemes that require credit sweeteners, someone has to pay for them. The question remains: Who will be the patron next time? Absent an answer to this question most people say IMF SDRs. I think climate and social priorities forming strict use of proceeds of any new scheme bonds will be needed to secure a sponsor.

- Menu of options. There were choices for what sort of bonds the defaulted loans got exchanged for. Choices help a general framework flex to different countries and creditors needs.

- Complexity. While these bonds were complex and tricky to price, the banks were desperate to offload them. So their cheapness meant investor demand despite the headaches. While the Brady bonds did help recreate an emerging market bond market it took the best part of 15 years to shift away from their complexity to more standard bonds.

- Not suited to all debt crises. Other fixes were needed for countries with little or no market debt. The most audible debt alarm bells are linked to the IMF’s assessments of lower-income countries debt. Most of these countries have little or no commercial debt, so a Brady type plan makes little sense. In my book on Africa debt, I write that for these types of country the debt crisis resolution would require net concessional financing flows and debt reduction from official lenders (with a scheme more HIPC or MDRI workouts of the 1990s).

- Corralling creditors. For the Brady Plan, the main creditors could get around the table.In recent times China, India and the Gulf countries are much larger creditors than in the 1980s. For the 1980s debt build, the petrodollars were recycled via the international banks but this time they are being lent sovereign to sovereign. This has made the official debt workout system look outdated, as many countries are not members of the Paris Club. An effective debt rescue requires that all major creditors can negotiate at the same table. The diverse set of creditors might leave quick debt resolutions at the mercy of wider geopolitical events.

Does Brady 2.0 make sense?

While there are important lessons from the Brady scheme, simply dusting off the paper work and rebranding it the Yellen plan does not make sense. There’s a need to sift through the lessons and design something suited to the current debt landscape.

One other consideration is the uncomfortable truth is that any scheme that successfully reduced debt burdens would be followed by a new round of borrowing. So providing a treatment without an attempt to solve some of the underlying causes of debt crises would be folly. Debt problems are often linked to a lack of government revenue, or investment problems (e.g. the proceeds of debt are not invested well). So support needs to be conditional on efforts to improve these area, particularly to encourage that the proceeds of new lending are invested well. A clear focus on economic, green or social objectives might also encourage more development capital to flow.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.