Five takeaways from the IMF’s spring meetings

After a trip to Washington DC, for the IMF and World Bank Spring meetings, here are five thoughts. These were gathered from various panels and meetings with finance ministers, Central Bank Governors, plus IMF and World Bank staff. While the best insights were country specific, there is a lot of macro driving markets right now and several important global themes to track.

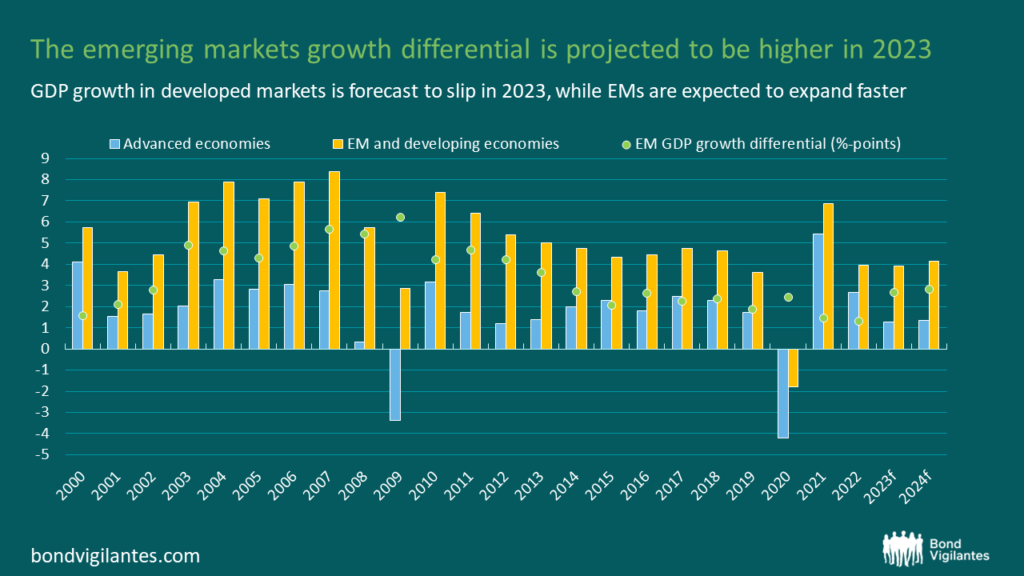

1: Global economic growth: it remains a recovery, albeit a “rocky one”, with emerging markets better placed relative to developed markets

Slower growth of the global economy of 2.8% is forecast in 2023 (versus GDP growth of 3.4% in 2022) according to the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook (WEO). So while it remains a recovery it could end up being one of the slowest years of expansion since 2001, besides the Global Financial Crisis and the 2020 pandemic recessions.

Despite the projected slowdown of global growth, the emerging market growth differential has improved, with emerging market and developing economies set to grow faster (+3.9%) than advanced economies (+1.3%) in 2023. The strong performers are in Asia and Africa, bolstered by India (+6.3%) plus a re-opened China (+4.5%). On the flip side, a few mild recessions are forecast in 2023 by the IMF, including the UK (-0.3%) Germany (-0.1%). More surprisingly, the IMF is not forecasting a recession in the US (+1.6%).

More worryingly among emerging markets are forecasts of stagnation in South Africa (+0.1%) and Brazil (+0.9%), where—in the absence of growth—austere fiscal policy is being used to stabilise public debt.

The IMF WEO data comes with a lot of long documents. One of the analytical chapters I enjoyed was on sovereign debt. The key point made was that debt-reduction is as much about growth as it is about fiscal consolidation. This is obvious to most, but good to see the IMF saying, in a further departure from a focus on austerity as a fix to all problems. The IMF writes that: “debt-reducing effects of fiscal adjustments are reinforced when accompanied by growth-enhancing structural reforms and strong institutional frameworks” and that “ …economic growth and inflation have historically contributed to reducing debt ratios”.

The biggest risks to global growth discussed at the meetings were either linked to potential collateral damage from the Federal Reserve’s hiking cycle or geopolitical in nature. One of the main IMF concerns about global financial stability is: “Rising geopolitical tensions among major economies have intensified concerns about global economic and financial fragmentation, which could have potentially important implications for global financial stability”.

Source: IMF WEO April 2023

2: Mixed views on US inflation and the Fed’s response

The IMF also writes that: “the anemic outlook reflects the tight policy stances needed to bring down inflation, the fallout from the recent deterioration in financial conditions, the ongoing war in Ukraine, and growing geoeconomic fragmentation. Global headline inflation is set to fall from 8.7 percent in 2022 to 7.0 percent in 2023 on the back of lower commodity prices, but underlying (core) inflation is likely to decline more slowly”.

Debate remained throughout the Spring meetings about how far the Fed is from the end of its hiking cycle. Views differ on the extent to which US inflation is falling. People seem to take whatever message they want from US employment numbers, but there seems to be more consistent reading from measures of US underlying inflation, with most saying “it’s on a decelerating path” (though some still think a re-acceleration has a decent probability).

There was also interesting chatter on the role of expectations in generating inflation. In the past we’ve assumed expectations impact inflation on a 1-2-1 basis too much in our theory and models. While more recently it’s been fashionable to say the impact of expectations on inflation is zero (which feels equally wrong despite us not being able to measure the impact of expectations). So maybe we settle on it matters somewhat? Some firms’ prices adjust to match or get ahead of inflation, some just catch up.

Worries persist over whether more cracks will open in global finance after US and Swiss bank failures. But while the IMF notes the “considerable strains as rising interest rates shake trust in some institutions”, they make it clear that they think “it’s not 2008”. The IMF worries are focused on the risk of deeper recessions that markets are pricing and or inflation accelerating, which would deepen stresses and erode trust in the financial system.

3: Emerging Markets investor sentiment is better

At the October 2022 meetings, investors seemed totally downbeat and exhausted by 2022. A new year has helped, even if the January the emerging markets rally got wiped out by the Fed, plus US and Swiss bank failures. The better sentiment reflects a view that the Fed will at some point soon stop hiking (via a US recession or labour market cooling), that the US dollar is now much softer than at its 2022 peak, and with high-yield spreads again historically wide. The view is that emerging markets spreads should be wider than, say, 2019 (there are valid debt and fiscal concerns), but not this wide.

Any optimism is offset by concerns about advanced economy recessions and the lack of clearly compelling stories in hard currency debt in emerging markets. Hence the biggest debates occur when investors are comparing between emerging markets. There was less talk than I expected about Russia’s invasion. And no-one seems to mention the pandemic anymore.

4: We (still) need a better way to solve sovereign debt blow-ups

There is a general fear of rising debt levels. Most of the alarm is about low-income countries that are not in the markets, but there is still some valid alarm about wider emerging markets. No-one is saying a crisis will be “systemic”, but most are expecting more than just a trickle of sovereign defaults in the coming years.

Right now several emerging markets are awaiting restructuring. Venezuela and Lebanon are still going nowhere, but the drag is domestic. Suriname, Ghana, Zambia and Sri Lanka are making some (but slow) progress. Meanwhile Ukraine, Russia and Belarus debt workouts are linked to how long the war persists.

Debt restructuring for Zambia and Sri Lanka (and to a lesser extent Ghana) has been slow because of the tricky official creditor mix, which includes the traditional (Paris Club members) and recently scaled-up (mainly China, but also form the Gulf and India). The problem is they cannot all agree. Without their financing assurances, the IMF cannot proceed with its programs and they are important as the IMF is typically an umpire in debt restructuring.

Efforts have been made to solve this impasse via the G20 common framework, which aims to get the main creditors around the same table to talk. The major recent development has been to clarify that this table is round. The new Sovereign Debt Roundtable met during the Spring meetings, to get creditors, new and old, to agree and coordinate. During meetings, they agreed to: (i) provide information to creditors on macro and debt sustainability earlier; (ii) drop the sequential approach and negotiate in parallel; (iii) agree on role of multilaterals not to provide debt relief but instead provide net concessional money, as grants where possible; and (iv) plan a workshop in May to improve understanding on comparability of treatment.

5: Climate and development money calls and (absence of new) pledges

There is still a strong call from the official sector on the need to provide more financing for developing countries, whether to “avoid lost decades”, for net zero, or to be more resilient to climate shocks. It mirrors the Climate COP in that sense. Most conferences talk of multiple recent shocks that have elevated food and energy prices.

However, no rich country is willing to provide more cash at the moment. The West seems to be reducing aid, China’s lending is way down from the peak (as they take loses on past Belt and Road loans), and the Gulf is shifting from deposits and handouts to investment opportunities.

You still get the “use IMF special drawing rights” answer to financing gaps, but there are technical issues with no real drive beyond some extra lending by the IMF.

The only new disbursing climate money at the moment is the IMF’s Resilience & Sustainability Trust that provides countries on the program with some extra 20 years of concessional money for climate goals. It is set to expand this year, and they have about $45bn to share, so it’s helpful but the size means it’s not a game-changer. Frontrunners for the trust are Rwanda, Barbados, Costa Rica, Bangladesh and Jamaica.

There was lots of talk about the incoming World Bank President and orienting the organisation towards a climate rather than poverty reduction goal. And more generally, for multilaterals to leverage balance sheets to lend and guarantee more.

Conclusion

The meetings once again provided a wealth of insight. Commentary on macro market drivers, expert opinion on geopolitics and country level insights, can all be put to work in our management of emerging market bonds funds. While you could navigate the virtual version of these fora in 2020 and 2021 from your desk, you now need to be in DC again to get the best insights. Where else can you meet 30 finance ministers and Central Bank Governors in just a few days?

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.