Housing and the Fed – how low will rates need to go?

Central banks have traditionally relied on interest rates as a primary tool to influence economic activity, raising rates to cool down an overheating economy, and cutting rates to stimulate growth. Historically, these mechanisms have worked fairly well; however, the recent cycle has proven to be different. Despite a series of aggressive rate hikes, the expected economic slowdown has been surprisingly muted, suggesting that economies are now less sensitive to interest rates. This raises a crucial question: if recent rate hikes haven’t significantly slowed the economy, how can we assume that traditional rate cuts will effectively stimulate it? And just how low must rates go to have an impact?

The housing market serves as a key channel for monetary policy transmission, making it essential to examine how it has responded to recent rate changes. Historically, the transmission mechanism from monetary policy to the housing market, and subsequently to the broader economy, was straightforward (as discussed here). However, this mechanism has become less predictable, especially post-financial crisis (discussed here). This monetary mechanism is not working as normal due to the unique nature of the current housing market.

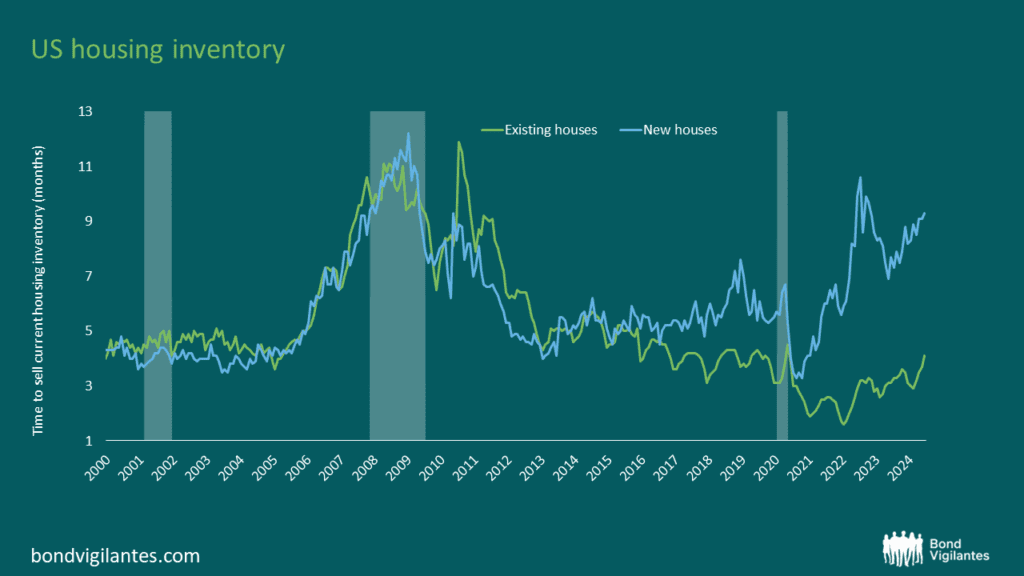

The strength of the housing market depends on the balance between supply and demand. The housing inventory chart below illustrates the current bifurcation in this market, showing a sharp divergence between the average time new and existing homes stay on the market, with the availability of existing home inventories remaining low due to homeowners’ reluctance to sell, while new home inventories have risen as affordability challenges deter potential buyers:

Source: M&G, Bloomberg, 30 June 2024

On one side, existing homeowners, who have locked in historically low mortgage rates, have little incentive to move, since doing so would mean giving up those competitive rates. On the other side, new homebuyers are willing to buy but cannot afford to, as elevated mortgage rates have made housing largely unaffordable for them.

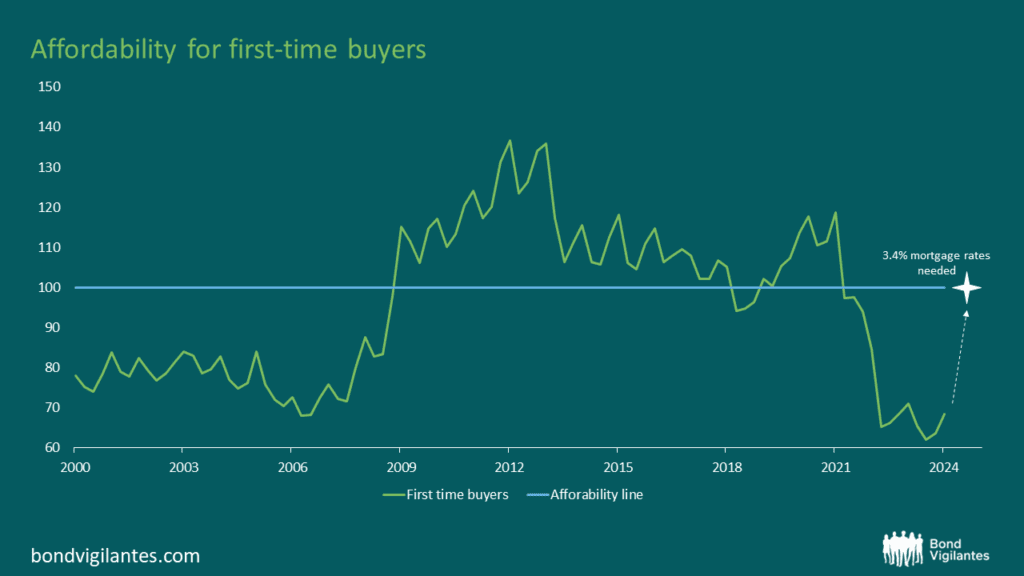

We therefore need to understand what level of rates is required to restore balance in the housing market and stimulate activity again. Starting with first-time buyers, the chart below shows their level of affordability, which, not surprisingly, is historically low. In order to restore affordability in this market, the line would have to return to 100, meaning that a median family would have just enough income to qualify for a mortgage loan on a median-priced home. To achieve this, we calculate that mortgage rates would need to drop to 3.4% (assuming all other factors remain constant).

Source: M&G, Bloomberg, August 2024

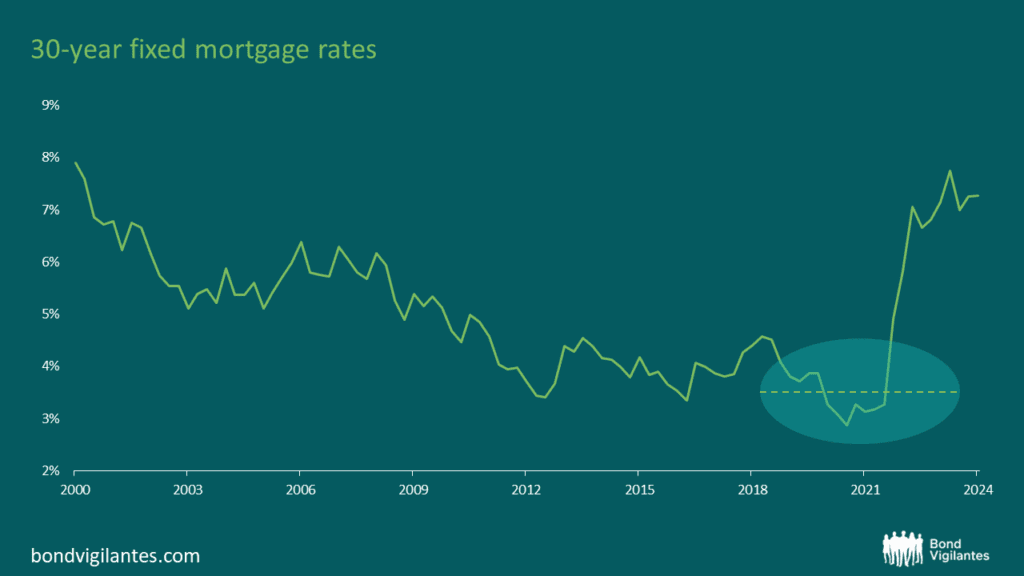

The situation with existing homeowners is different. For them, affordability is generally not an issue, given their lower loan-to-value ratios (LTVs). Instead, it is a matter of incentive. Aside from some exceptions, most people are not willing to move and thereby give up their extremely competitive mortgage rates. To incentivise most existing homeowners to move, rates would need to fall to levels similar to those they originally locked in. This would be around 3.5%, which is the average mortgage rate available during the period around COVID-19, when many either bought a house or refinanced their existing debt.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg, as at 30 June 2024

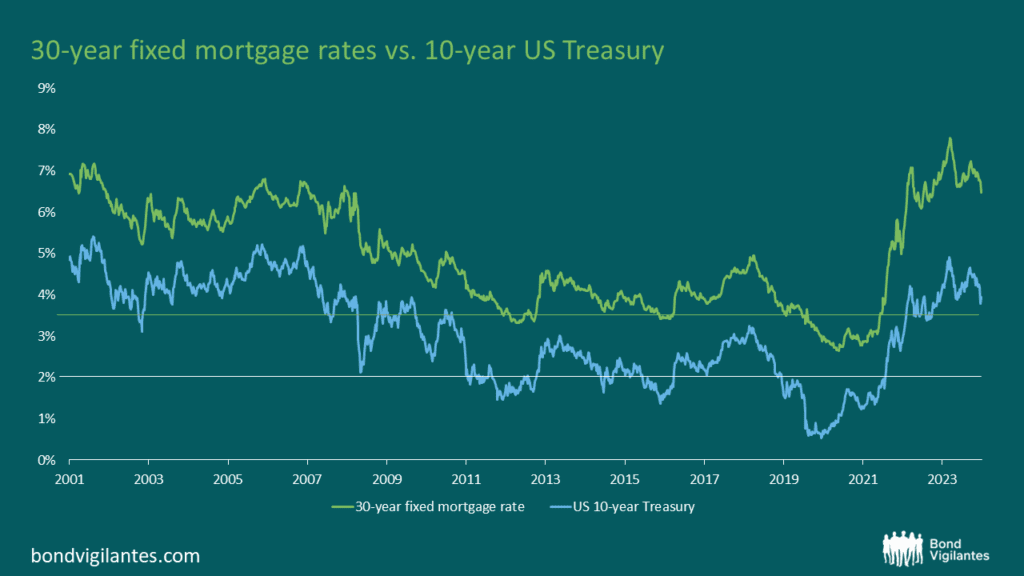

In conclusion, the transmission mechanism of interest rates has been dampened in the restrictive phase and will likely remain less effective in an easing phase. To effectively stimulate the U.S. economy through its housing channel, mortgage rates might need to fall significantly. Our analysis indicates that to restore activity in the housing market, mortgage rates might need to drop to around 3.5%. Historically, this would correspond to a reduction in the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield, potentially towards 2%, depending on broader economic conditions and Federal Reserve policy.

Source: M&G, Bloomberg, August 2024

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.