Emerging markets: In need of a new definition

Emerging market (EM) bonds have had an impressive year so far, delivering double-digit total returns across both hard and local currency. This compares favourably with developed market (DM) bond returns, and so EM should continue to attract crossover investors who have the mandate to allocate some of their capital to EM when they see fit. Nowadays, the investment rationale is often reinforced by a popular argument that some of the developed markets have recently witnessed high policy uncertainty which was more prevalent only in EM in the past. Ongoing US tariff-related noise, perceived threat to independence of the Federal Reserve under President Trump and prolonged political instability in France are perhaps the most vivid examples of that. However, it is worth noting that the convergence between EM and DM is also happening from the other side – through significant improvement in the quality of policy and institutions across many EM countries in the past decade.

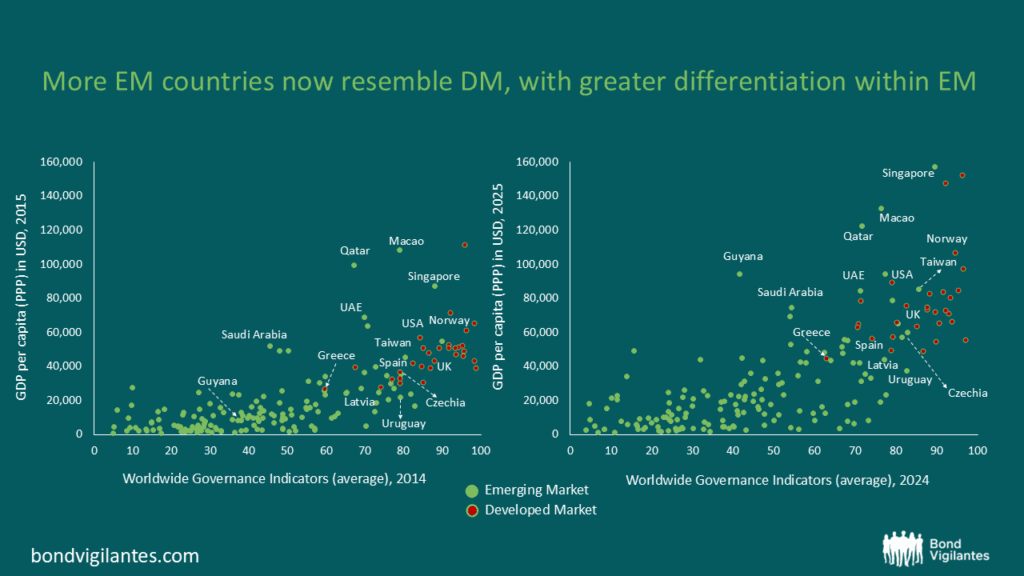

Source: Source: IMF, World Bank, Bloomberg. Note Red dots denote developed market countries defined as those outside both JP Morgan EMBI and CEMBI indices.

It seems that the division between EM and DM has indeed become more blurred in recent years. With this in mind, it may make sense to revisit the definition of EM. The simplest answer is that a strict commonly accepted definition does not exist. As outlined in World Economic Outlook (WEO) regularly published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the differentiation between EM and DM (“emerging and developing” and “advanced” economies, as per the IMF language) is not based on strict criteria and evolves over time. According to the IMF, they use factors such as per capita income, exports of diversified goods and services, and degree of integration into the global financial system. In its latest WEO (October 2025), the IMF lists 42 economies as “advanced”. The list has slightly expanded in the past decade, with the most notable additions including Croatia and Israel. It will be interesting to see whether Bulgaria will follow Croatia’s recent example and be reclassified as “advanced” after it enters the euro area in January 2026. This would allow it to join the list of all other Eastern European euro area members which the IMF already considers “advanced”.

Meanwhile, the market tends to focus more on the JP Morgan definition of EM countries, as its EMBI indices are widely used as benchmarks by EM investors. This classification differs significantly from the IMF’s approach. For instance, JP Morgan considers Czechia, Croatia, Latvia and Lithuania as emerging economies, whereas the IMF classifies them as “advanced”. Surprisingly, Slovenia – despite having slightly lower per capita income levels (on a purchasing power parity basis) compared to Czechia – is somehow not an emerging market for JP Morgan. Meanwhile, this year JP Morgan also excluded Qatar and Kuwait from EMBI due to high per capita income levels; the UAE could follow suit in 2026.

Adding to the complexity, JP Morgan‘s CEMBI index has different country inclusion guidelines, compared to EMBI. For example, corporates and banks from Qatar and Kuwait remain in CEMBI despite their home countries having been recently excluded from EMBI. In any case, their EMBI exclusion will certainly result in some divestment and some change in investors’ perception too. In another example, CEMBI also includes corporates from Israel, South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao – all of which IMF considers as advanced economies.

As a simpler attempt to distinguish between EM and DM, one may want to take look at a combination of per capita income levels and governance levels. While there are certainly many other indicators (such as degree of exports’ diversification) that can complement these two, their calculation and interpretation can often be more complex. Per capita income (measured by GDP per capita on a purchasing power parity basis) remains an undisputed indicator of a country’s development level. However, the importance of governance seems to be sometimes overlooked. For example, the recent rapid growth in oil production in Guyana has propelled its GDP per capita to levels exceeding those of many developed countries. However, on its own, this clearly does not make Guyana a developed country, particularly given its governance standards have remained at relatively low levels. Quoting the World Bank, good governance helps countries “increase economic growth, build human capital, and strengthen social cohesion”. In other words, high quality of institutions reduces the risks of abrupt changes in policies and severe deterioration in macroeconomic fundamentals that can impact a country’s creditworthiness. While numerous governance metrics are published by different institutions, the Worldwide Governance Indicators prepared by the World Bank stand out as among the most objective, consistent and comprehensive. These indicators encompass six key dimensions: Voice and Accountability, Regulatory Quality, Political Stability, Rule of Law, Government Effectiveness and Control of Corruption indicators.

Looking at the latest available data, we can make a couple of interesting conclusions. Firstly, there is no longer a significant difference between DM and a large number of EM countries, especially regarding governance standards. For example, Uruguay (an EM country according to JP Morgan and the IMF) has overall stronger governance compared to the USA, in particular regarding political stability, control of corruption and voice and accountability. In another example, Czechia has both stronger governance and a slightly higher per capita income level compared to Spain, yet it is considered an EM country by JP Morgan in contrast to the latter. (As an aside, due to much stronger macroeconomic fundamentals Czechia is also rated 1-3 notches higher than Spain by the three main credit rating agencies).

A second conclusion from the data is that there is still a large differentiation in terms of governance and per capita income levels within EM universe itself. This differentiation has only increased over time, as many EM countries seem to be stuck at low governance and income levels, while others have made significant progress in both. (We explored EM governance trends in more detail in this article: Governance Standards in EM: Diverse Country Trends Don’t Go Unnoticed by the Markets.) In other words, simply being classified as part of EM universe now tells investors very little – it could be anything from UAE with very high income and relatively strong governance to Cameroon, where both are very low. So perhaps instead of sticking to the conventional yet inconsistent definitions, it is now time for the market to start developing a new, more transparent and granular classification which would better reflect today’s evolving reality.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.